Shortly before the pandemic began, for reasons I’m faintly embarrassed to admit were as much recreational as professional, I attended an hour-long prepping workshop in Central Park. Shane Hoebel runs among the most visible wilderness survival schools close to New York City; for a few hundred bucks, he’ll take novices into the woods upstate for a weekend and teach them how to make a fire with flint and properly wield a knife. Hoebel once made a cameo in a New Yorker story, using Apache techniques to track down a panther that was said to be roaming celebrity neighborhoods upstate—which is to say he’s a theatrical guy, particularly well suited to stoking white-collar office workers’ latent desire to wield hatchets and imagine themselves escaping Manhattan before flames engulf the island.

Hoebel started out with primitive camping and, as interest in go-bag recommendations and budget bunkers increased over the past decade, developed his business into something more recognizably doomsday-adjacent. He makes a lot of money, he told me, running military-style training sessions for guys in the city concerned about the next 9/11 or economic collapse. He’s also one of the handful of preppers who are always ready to dispense advice when Americans are starting to feel anxious: Last year, in addition to pandemic advice, he appeared in the national press to explain how to survive both the collapse of a building and the climate writ large. Being a fairly reasonable guy, he hasn’t yet waded into nuclear winter territory, though I suppose there is still time.

On the morning of February 24, Vladimir Putin announced Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, implicitly threatening nuclear retaliation should any other government intervene. Naturally, one of the less consequential results of this speech was to kick the survivalist community into overdrive.

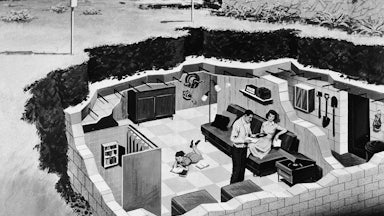

The enduring image of the fallout shelter notwithstanding, a nuclear strike is among the events for which it’s most futile for a person to attempt to prepare: That solar-powered satellite phone won’t do shit if there’s no sunlight, and it’s doubtful a closet full of beans will be useful if you’re instantly vaporized—or, probably worse, suffering the effects of radiation poisoning and waiting for your insides to bleed out (potassium iodide, despite the hype some preppers were giving it even before the invasion started, has its limits). But then again, this is a country in which an airborne pandemic inspired people first to buy toilet paper and then to purchase an estimated five million more guns, the jokes about Americans trying to shoot the virus into submission rendered absurdly concrete.

In moments of crisis—presidential elections, pandemics—a certain kind of survivalist tends to appear in the mainstream press, offering advice that’s usually equal parts self-help and product review. They tell the public to remain calm, to take incremental steps toward stocking their pantry, to make sure there are enough medical supplies and maybe a water filter in the home. It’s advice tailored to a population that can’t afford a bunker but maintains that a disaster is usually a single event that can be weathered inside the home. The outlook has proven particularly ill suited to address, for instance, the roiling pandemic that, nearly three years later, continues to kill thousands of people every day. In March 2020, nearly every national publication ran a story asking preppers for advice; despite all those go-bag recommendations, though, the pandemic remains, a reminder that some crises require people to act in interests not limited to their own.

Predictably, the prepper cycle has returned along with the threat of World War III, though the talking points are particularly ludicrous when laid out next to the potential threat. The manager of a Texas survival shelter business says he’s already sold five bunkers since late February, each one costing between $70,000 and $240,000. A company selling freeze-dried meals published a color-coded map of caves across the United States that might reduce the chances of radiation poisoning should a person manage to “go deep” and have enough supplies. It’s also selling kits that allege to remove radiation from the food it provides at a discount of $74.99. A kid on TikTok who goes by “the Novice Prepper” has been going viral with tutorials such as “how to survive nuclear fallout with no basement,” though I personally won’t be using his advice. And recently there was a remarkable headline, even for The Sun: “I’m a doomsday prepper and here’s how you could survive nuke disaster as Ukraine-Russia tensions threaten WW3,” featuring the tech CEO turned prepping influencer John Ramey, a man who refers to himself as Silicon Valley’s first “outed” survivalist. (And who, it probably deserves to be noted, would have a good chance of surviving most crises, not because of his specialized skills but due to his astronomical wealth.) Ramey told the outlet he thinks it’s important for people to have an emergency fund with three months’ worth of expenses and a two-week supply of any resources a family might need. The survivalist and technology blogger Josh Centers, who contributes to Ramey’s website, The Prepared, has fairly similar advice, with the additional tip of stocking not just potassium iodide but possibly miso to counteract the effects of radiation poisoning—though Centers is “skeptical,” he says, “medical staff working in the aftermath of the Nagasaki bombing found that they were unaffected by radiation poisoning when they regularly ate miso soup.” Recently Centers was hassled a bit for a tweet in which he referred to nuclear war as a terrible thing but “more survivable than you think.” “The key to survival,” he wrote, “is realistic optimism and a positive mental attitude.” And then he linked to a post about how to stockpile food.

Centers has a real talent for distilling a certain kind of prepper ideology into its most absurd form: The man wrote a jingle with his wife that went, in part: “For World War III, I bought a couple of buckets and hit the Dollar Tree.” But how different is that, really, from running war simulations with Wall Street workers or pointing out the location of caves? As preppers become media personalities in their own right, giving nearly identical advice for every conceivable scenario, I’d argue their prominence has a bit more to do with the kinds of disasters Americans are capable of imagining—disasters in which only a few well-stocked households survive. Of course it’s nice to think about casting yourself in an action movie. And it’s comforting to believe that a little common sense and the right gear could get a person through a calamity. But taken to its natural conclusion, all this advice is pretty grim, a series of prescribed preferences and tastes in the place where civic action or at least neighborly concern could be. Imagine you took to the caves and ate miso paste and emerged into nuclear winter more or less unscathed. What’s even the point if you’re the only one to pull it off? Why would you want to survive?