Growing up in rural West Virginia, Paul Darwin Picklesimer (they/them) strove to follow their mother’s advice: Don’t push your personal beliefs on others. So when Picklesimer perceived animal abuse while reroofing barns with their dad, they would try to “find a balance of putting a seed in someone’s mind to show that animal’s perspective a bit, without trying to tell people what to do.”

Years later, Picklesimer faces charges of trespassing, theft, and burglary as part of criminal proceedings in three states. In each case, Picklesimer and other animal activists broke into farm and animal testing facilities, where they recorded the prevailing conditions and “rescued” the animals therein. Total penalties span nearly $332,000 in restitution debt and potentially decades in prison.

In the most widely publicized case, Picklesimer and other activists, including Wayne Hsiung, co-founder of animal rights group Direct Action Everywhere, or DxE, entered Circle Four Farms, a massive Utah pig facility owned by Smithfield Foods, in 2017. The activists filmed the pigs’ conditions, whisked two piglets away to safety, and sent the footage to the news media. With Smithfield’s backing, Utah prosecutors filed felony charges.

Several other activists have since taken plea deals that prevent them from publicly disparaging the company. But Picklesimer and Hsiung have declined similar offers. Instead, they’re pressing for a trial they hope will go down as a pivotal moment in the history of the animal rights movement. They seek to convince a jury that the moral urgency of saving the piglets at Circle Four Farms justified the alleged crimes, establishing a landmark legal precedent that incorporates a factory farm animal’s suffering into the law’s moral calculus. Whether they will be permitted to make this argument at all will be determined by a Utah judge, following a major pretrial hearing set to take place Thursday.

The protracted case is one of several involving DxE activists, whose tactics testing the frontiers of the law distinguish the group in an animal rights movement that has recently been inclined to work squarely within the legal system.

It also comes at a moment when the fight for the cause of nonhuman animals is bedeviled by what many suspect are mere illusions of progress. In the United States at least, an emerging consensus condemns the treatment of livestock as practically and morally unacceptable. Yet substantive signs of change are murky, at best. Humans claim almost limitless primacy over agricultural animals—reflecting a deeply rooted, and possibly rotten, economic and spiritual order. What would happen if its legal foundations were exposed to the light?

In 2002, activists from the Utah Animal Rights Coalition, or UARC, walked into Circle Four Farms to document the lives of the pigs inside. The resulting 20-minute video they produced showed distressed, feces-covered pigs tramping on metal grates, avoiding corpses. Activists walked out with two pigs that they said were lethargic and in need of medical care.

This was a textbook “open rescue”—a novel practice in vogue at the time among animal rights groups, said Jeremy Beckham, the executive director of UARC and a longtime activist. In open rescues, participants would reveal their identity, secure in the belief that their moral high ground would give them the advantage on legally dubious terrain. The tactic contrasted with the more militant approach of, say, the Animal Liberation Front, whose members were more likely to don ski masks and open cages at a mink farm, or break equipment of a vivisection lab, remaining anonymous in order to strike again.

In the 2002 case, prosecutors did not charge the UARC activists with crimes. A Circle Four spokesman told The Salt Lake Tribune at the time that a prosecution “could potentially create more publicity, which is exactly what [the animal rights activists] want.” This was common practice at the time. “No one was getting charged,” said Beckham.

But change was afoot. After 9/11, the federal government obsessed over the threat of eco-terrorism. Wiretaps and informants helped law enforcement infiltrate activist communities. State “ag-gag” laws swept the nation, effectively criminalizing whistleblower and activist efforts to document animal agriculture operations. And the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act—passed nearly unanimously by Congress in 2006—gave prosecutors leeway to characterize as terrorist activity a disturbingly vague array of aboveground activist tactics (potentially including, in some readings, ordinary First Amendment activities like protests outside a meat executive’s home).

The tone darkened. People would show up to their first protest ever, Beckham said, and that weekend the FBI would knock on their door, asking for the names of fellow protesters. Hsiung and others said that, confronted with such zealous opposition, the U.S animal rights movement and its benefactors pivoted away from grassroots activism toward an institutional, “within the system” approach.

Hsiung, meanwhile, was moving in the opposite direction. After receiving his law degree, he became a visiting faculty member at Northwestern University at 25 years old. Despite “superficial indicators of success,” he felt himself “a spiritual failure”—and a poor fit for the academy. Aside from his friendships with animals, he’d been lonely and depressed for much of his life, an experience that seemed unlikely to change. There was a “reasonable chance” he was going to kill himself, he said. “And I thought, ‘If you’re going to do this, you really should do some things that you really just ought to do.’ … And the individuals I wanted to help more than any other individuals were the animals on factory farms.”

One night in 2007, Hsiung walked through an unlocked door at Chiappetti Lamb and Veal, a vestigial slaughterhouse on Chicago’s South side. Hsiung had imagined such a place as a “huge dark fortress that was completely impenetrable and powerful,” he said. But suddenly, he realized how “trivially easy it was to walk in,” and, particularly if he had some help, “how trivially easy it would have been to walk out” with an animal in his arms.

Hsiung co-founded DxE in the Bay Area in 2013, while he was working as a corporate lawyer. That same year, Picklesimer moved to Chicago, where they distributed leaflets on the virtues of veganism and posted signs encouraging others to see Earthlings, a factory farm documentary.

One day in 2014, someone told Picklesimer that DxE activists planned to enter a Chipotle and tell the clientele about the “myth” of humanely raised chickens. Picklesimer didn’t relish the awkward confrontation: “I thought that sounds like a terrible protest, honestly.”

They attended nonetheless, and gradually fell in with DxE. Picklesimer was struck by an interview Hsiung gave on a podcast, in which he described a grassroots, historically informed theory of political change. And as Picklesimer moved past their personal discomfort, the activism itself was invigorating, too. “Once you go into a Chipotle and yell a bit and feel like you’re telling the truth,” Picklesimer said, “it starts feeling less authentic to do anything that normalizes the whole system.”

Normalizing the system is exactly what these activists felt the mainstream animal rights movement in the U.S. had started to do. Major institutions like the Animal Legal Defense Fund and the Humane Society of the United States pushed to criminalize discrete animal abuse while generally leaving “the capitalist structures that were pushing animal exploitation” unconfronted, said Justin Marceau, an animal law and policy scholar at the Sturm College of Law.

Occasionally, major legal efforts have advanced widely agreed-upon movement interests; Marceau himself helped represent a coalition that included the Animal Legal Defense Fund in a largely successful litigation effort to overturn state ag-gag laws on free speech grounds. But the movement’s legalistic turn, he said, left a vacuum on the left flank, which DxE promptly filled. In contrast to other groups careful to avoid liability, Marceau said, DxE is “so confrontational and so willing to say, ‘Well, no, the law is part of the problem. If they’re going to come after us, they’re going to come after us.’”

DxE was founded, Hsiung said, specifically to focus on open-rescue activism, rather than PETA-style blood-pouring demonstrations, or even the Chipotle confrontation that Picklesimer witnessed. Open rescues, Hsiung felt, were “respectful and humble in a way a lot of other extreme activism is not.” In a world in which many people feel little compunction mocking and slandering vegans as joyless extremists, Hsiung said he wanted to “empower ordinary people” to more fully enact their convictions.

Enter Picklesimer, who, upon arriving at DxE’s headquarters in Berkeley, California, in 2016, quickly distinguished themselves as a level-headed figure, uncommonly handy with tools. One day, Hsiung asked Picklesimer to take a walk. They discussed the legal risks of open rescues. Was Picklesimer in?

In the months before they entered Circle Four Farms under cover of darkness, Picklesimer and Hsiung participated in three other open-rescue operations, helping to remove two hens from a farm in California, four turkeys from a farm in Utah, and, shortly afterward, three beagles from a Wisconsin animal testing facility.

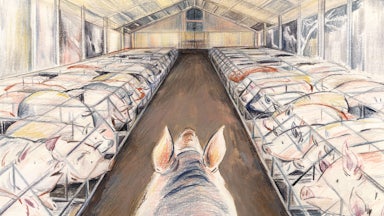

In the Circle Four Farms investigation, Picklesimer, Hsiung, and four others used virtual reality cameras to document the pigs’ living conditions. The 360-degree video they would publish showed a hectic scene, where live piglets crawled about the dead amid the cramped pens of their lethargic mothers. The activists removed two piglets whose prospects they deemed particularly dire—Lizzie and Lily, they would be named—and left them with animal sanctuaries in the region.

Weeks later, The New York Times reported on the V.R. footage. Then, according to The Intercept, the FBI raided area animal sanctuaries in search of the piglets. Local prosecutors charged the activists with four felony counts punishable by potentially decades in prison.

Circle Four Farms, which raises more than one million pigs annually, is owned by the somewhat iconic American brand Smithfield, which is itself owned by the Chinese meat processor Shuanghui International. The company rejects DxE’s characterizations of animal abuse. In court filings reported by the Tribune, an outside specialist said, after an audit, that she did “not have … concerns about the care of the animals” at the facility. And in a statement, the company’s chief administrative officer, Keira Lombardo, wrote that, at “Smithfield Foods, the care and safety of our animals is a top priority. The health and well-being of our farm animals is compromised when those claiming to be animal care advocates trespass onto farms, violate our strict biosecurity policy that prevents the spread of disease, and steal our animals.” Lombardo said that Smithfield has encouraged prosecutors to pursue the case against Hsiung and Picklesimer. The company, she wrote, would like to see the pair convicted.

Now years into pretrial wrangling, prosecutors have whittled down Hsiung and Picklesimer’s alleged crimes to trespassing, theft, and burglary—likely an effort, the defense team contends, to limit the scope of the case and thus the evidence that might be considered admissible. (Prosecutors did not respond to interview requests for this story.) Picklesimer and Hsiung’s actions were caught, of course, entirely on a camera. Yet, in a role reversal, they have pushed for jurors to see this evidence, while, in pretrial motions, prosecutors have argued that the V.R. footage—and really any discussion of inhumane conditions at Circle Four—would distract from the legal matter at hand.

Prosecutors want the case to hinge on the question of trespassing and property theft, court filings show. Hsiung and Picklesimer seek, instead, to focus on their intention to document and prevent ongoing animal abuse. Hsiung’s lawyer Elizabeth Hunt said in an email that she does intend to hold the state to its burden of proof on the charges of trespassing and theft. But the defendants have deeper ambitions. They seek to establish a landmark precedent that justifies their seemingly unlawful actions on the grounds that they prevented a greater evil from taking place.

If granted access to DxE’s footage, a jury would surely understand, said Hsiung, what it is like to see a struggling piglet who is a fraction of the weight of other piglets and has a “golf ball–size lesion on her foot and can’t walk anymore.” They’ll see why it was “such a desperate moment.… And why it was so necessary for someone to help.”

The necessity defense, as it is commonly known, is traditionally used in cases where, in the absence of a good legal alternative, a law is broken to avoid a greater evil (think running a red light to get someone to the hospital). As Jenni James, now a lawyer for People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, noted in a 2014 Stanford Journal of Animal Law & Policy article, the concept basically marks an “efficient breach of the criminal code,” which has “the power to transform a criminal defendant into a community hero—but the line between hero and vigilante is thin.”*

Judges, empowered to delimit the scope of a given case, have significant discretion to determine whether the necessity defense can be presented and effectively argued. And legally conservative by nature, they tend to be suspicious of this defense strategy, which rests on a moral argument that transcends the rule of law.

Still, the concept is not moribund. Last July, the Washington State Supreme Court made it easier to use the necessity defense in the context of climate change litigation. A Spokane activist faces criminal charges for blocking a train bearing fossil fuels, and the high court ruling will permit him to argue before a jury that, in his efforts to prevent environmental catastrophe, he had no reasonable legal alternatives at his disposal.

A successful necessity defense could embolden would-be vigilantes to break the law in the service of their own discrete moral convictions. But Hsiung, who says he has contemplated the defense since law school, albeit not with his own actions in mind, says that isn’t his goal. He says his defense has a specificity to it that would not necessarily apply in other contexts. It is “a way for us to acknowledge the sentience and moral status of animals.”

Under contemporary U.S. law and virtually all international law, animals are, with minor exceptions, treated as property, according to Margaret Riley, a historian and animal law scholar at the University of Virginia. In the U.S., nonhuman animals don’t have constitutional rights, and their relatively new statutory rights—which effectively encompass the right of a select subset of animals not to be abused—have severe limits. The Utah criminal code’s section on animal abuse, for example, which employs language common throughout the U.S., explicitly excludes “livestock,” so long as the conduct or care toward the creature “is in accordance with accepted animal husbandry practices or customary farming practices.” To the limited extent laws do theoretically protect piglets like Lizzie and Lily from abuse, in practice prosecutors rarely bring such charges against animal agriculture operations.

This fact, DxE hopes, will allow them to satisfy a core tenet of the necessity defense—that, given the limited options and the piglets’ plight, they had no other morally acceptable choice than to enter Circle Four Farms without permission and whisk them to safety. “If DxE felt like they could notify law enforcement, and they would step in and take animal suffering seriously, then they would have less justification,” said Matthew Liebman, an animal rights scholar at the University of San Francisco. “Until authorities do take animal suffering seriously, we are going to see more open rescues and more justification for them on the grounds that there’s no other means of protecting these animals.”

DxE’s methods can seem counterintuitive, characterized by the gamesmanship of the underdog whose backdoor tactics reflect long odds. Convicted in December for stealing a baby goat in North Carolina, Hsiung asked for prison time rather than probation, said Matt Johnson, a DxE spokesperson (the case is on appeal). Facing his own activism-related charges in Iowa, Johnson, mindful of prosecutors’ reticence to create martyrs, “kept the media dial down” in order to raise the chances that he’d be prosecuted. (Nevertheless, to his disappointment, on the eve of trial in January, prosecutors dropped the case.)

This legal strategy is part of DxE’s strategic road map toward its lodestar goal: an Animal Bill of Rights and an end to factory farming in the U.S by the year 2040. In an organizational network with dozens of chapters around the world, Hsiung’s influence runs deep. When, in 2020, he ran for Berkeley mayor (Picklesimer was simultaneously running for City Council; neither won) Berkleyside reported that “many DxE members venerate Hsiung and believe his smarts, charisma and strategic thinking are keys to the future of animal liberation.”

Others had been more skeptical. Shortly after the Times published its report on the Circle Four Farms investigation, a group of disaffected DxE members and others complained, in a letter detailing institutional failings, that Hsiung squashed dissent and breezily violated bylaws.

Later, in an open response to a journalist’s fact-checking queries, Hsiung contextualized and detailed what he said were inaccuracies in the letter, writing that one of the prominent authors later disavowed many of its claims as unsubstantiated. But he acknowledged that, during a period of institutional sturm und drang, “I did not give my personal relationships the time and attention they deserved, and I did not support certain key team members in the way that they deserved. My communication in conflicts was often cold and not empathetic, and reading some of it today makes me cringe.”

Looking at the whole of the animal rights movement, Beckham, of the Utah Animal Rights Coalition, fears it has lost its real-world organizing impulses, that it stands at a “low moment.” Even as the pandemic thrust the deleterious economic, ecological, and public health effects of animal agriculture into the public eye, he thinks that activist conversations have often become insular and that the average person on the street is less likely to have animal issues on their mind than they were 20 years ago. He doubts that’s “because we haven’t had some sort of esoteric legal breakthrough.”

Hsiung, who said he stepped down from formal leadership in DxE in 2019, however, sees in the courts a unique capacity to confer credibility upon a previously marginal moral position—and bring new people into the fold. Mentored by the influential legal scholar Cass Sunstein, Hsiung puts great stock in the power of social norms. “No one wants to get left behind,” he said. What is important for the movement is not just that there’s a lot of people behind it but that the “rate of change is increasing.” And “when you win legal and political victories like this, it gives other people the sense that the writing is on the wall … and that is when you start seeing the avalanche of social change.”

Depending on where you look, this avalanche is either imminent or chimeric. Prominent Michelin-starred Manhattan restaurant Eleven Madison Park has gone vegan. Plant-based meats are ascendant. And polling suggests Americans are increasingly willing to express a desire for a new animal rights regime that far outstrips the status quo.

Yet the bare fact remains that per capita meat consumption in the U.S. and the world—particularly in countries with developing middle classes—continues to rise. “If you think there’s a revolution in the works,” said Hsiung, “you’re not looking at the numbers.” And the industry’s lobbying strength is only growing. The U.S. pork industry has undergone massive consolidation in recent decades, squeezed out small farmers, and become a worldwide economic powerhouse. In 2020, U.S. pork exports alone valued $7.7 billion.

Back in in Hancock County, West Virginia, Picklesimer’s case has radicalized at least one person. Elaine Picklesimer, now widowed and newly vegan, watches her kid’s case against the company she calls “Shitfield” with pride. Paul has a chance “to make something that is very wrong right, and he’s working toward that goal. And I’m very proud of him,” she said. “I don’t want him to have to go to prison. But if he has to go, he can do it. And there will be others behind him that will take his place.”

* This piece originally misstated the journal in which James’s article was published.