David Weil’s nomination to be administrator of the Labor Department’s Wage and Hour Division has drawn opposition from the business lobby because the last time he had this job, during the Obama administration, he had the temerity to try to enforce the nation’s wage and hour laws. Earlier this week, I described how Weil attempted to revive enforcement of the overtime provisions in the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act, or FLSA. Today I’m going to talk about how Weil sought to crack down on the illegal misclassification of employees as independent contractors, popularly known as gig workers.

In July 2015, Weil issued Labor Department “guidance” on worker misclassification. A guidance document is a more informal alternative to a regulation. It doesn’t require, as a regulation does, public posting before it’s finalized followed by a period of public comment. It is not, as a regulation is, legally binding. It’s just an informal statement of how a given agency intends to apply the law. Businesses find guidance documents extremely valuable in figuring out how to interpret laws that affect them.

The gig economy is a tricky area because some gig workers enjoy being classified as independent contractors; it grants them certain freedoms they wouldn’t have as employees. Other workers don’t especially like being classified as independent contractors because it strips them of various legal protections, such as FLSA’s guarantees of a minimum wage and overtime pay, workers’ compensation, and unemployment insurance. Employers love assigning work to independent contractors. It’s cheaper, especially when you figure in that the employer doesn’t have to pay payroll taxes on an independent contractor.

The gig economy is a big story because a lot of people have taken rides on Uber or Lyft or stayed in people’s homes courtesy of Airbnb. Journalists are especially sensitive to the issue because much of the profession operates on an independent-contractor basis, not always willingly. But the truth is that the percentage of the workforce classified as independent contractors in 2017, the last year for which data are available, was fairly small—6.9 percent. That’s a smaller slice than in 2005—four years before Uber’s founding and three years before Airbnb’s—when independent contractors represented 7.4 percent of the workforce. A December survey by Pew found that the percentage of Americans who reported ever working via an online gig platform was only 16 percent. So there’s really no such thing as a “growing” gig economy—not at the moment, anyway.

I mention all this because Weil’s critics from the business world have accused him of trying to reestablish “an outdated workforce model that no longer serves a majority of Americans,” to quote the App-Based Work Alliance, an industry coalition bankrolled by Uber, Postmates, Doordash, Lyft, and Instacart. Despite what these gig companies say, being an employee is not “outdated.” For better or worse, the overwhelming majority of us still work for The Man, and the percentage of us who work for ourselves is shrinking, not growing.

The Fair Labor Standards Act defines the word “employ” as to “suffer or permit to work.” In plain English, that means an employer either requires a person to work or knowingly allows that person to work. Assorted Supreme Court decisions over the years have added somewhat more precise conditions. Is the work an integral part of the business? Is the relationship nontemporary? How much of the facilities and equipment have been provided by the worker? (If the answer is “little or none,” that person is likelier to be classified by law as an employee.) How much control does the business have over the worker? And so on.

To review these legal parameters is to be struck immediately by the fact that an awful lot of today’s gig workers (including anybody working full-time for Uber or Lyft) are probably misclassified employees. Weil’s guidance on gig work didn’t really break new ground. It merely described a legal framework that had been around for years and concluded, accurately, that the government’s definition of employment was pretty broad. “The ultimate inquiry under the FLSA is whether the worker is economically dependent on the employer or truly in business for him or herself,” Weil wrote.

If the worker is economically dependent on the employer, then the worker is an employee. If the worker is in business for him or herself (i.e., economically independent from the employer), then the worker is an independent contractor.

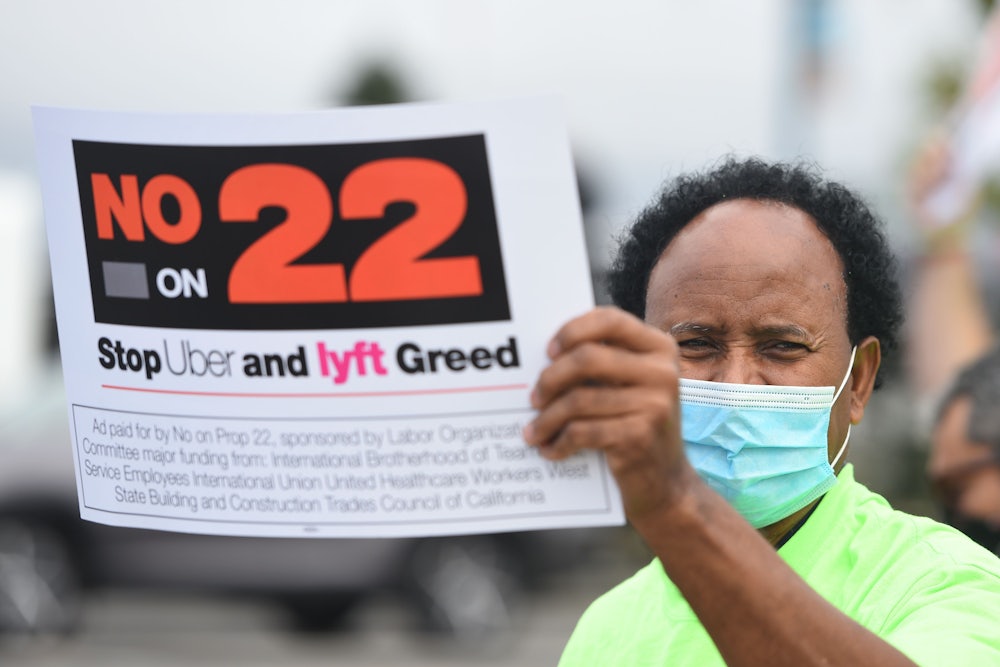

Weil has been accused of plotting to apply to federal law California’s “ABC test,” which the state uses to determine whether an employee is misclassified as an independent contractor under California’s controversial 2019 worker misclassification law, Assembly Bill 5. California’s ABC test is based on three considerations. To be classified an independent contractor you must be free from control by your client; you must perform work that’s outside the usual business performed by that client; and the contractor must be performing the same sort of work he performs for other clients. That’s admirably simple, and some people say it’s too simple. In November 2020, California Proposition 22 exempted app-based drivers from A.B. 5, effectively gutting it. The measure passed by a wide margin, but this past August a California state judge declared Prop 22 unconstitutional and tossed it out. The state attorney general is now appealing that decision.

Weil is not trying to apply the California test to federal law. In 2015 he issued a guidance, not a regulation with the force of law. Weil’s 2015 advisory was much less restrictive than A.B. 5. Asked at his confirmation hearing, back in July, whether he would impose California’s ABC standard, Weil pointed out that he couldn’t very well do that unless Congress amended the FLSA.

In truth, the business lobby isn’t afraid that Weil will apply some exotic new standard for determining whether somebody working off the books is a legitimate gig worker. It’s afraid that Weil will apply existing standards we’ve had for decades but have not, in recent years, enforced with much vigor.

In my next and final installment of the Weil Chronicles, I’ll write about the third reason the business lobby opposes Weil, which concerns his position on franchising. I’ll also discuss Weil’s important 2014 book, The Fissured Workplace, which provided an analysis of what’s happened to the labor market over the past half-century that’s much more thoughtful and complete than the usual ill-informed complaint that the gig economy is taking over America. What’s really happening is, I’m sorry to report, more sinister than that.