Each year, some 3.5 million tourists visit Cherokee, North Carolina, nestled along the Oconaluftee River in the Great Smoky Mountains. The main street of Cherokee, Tsali Boulevard, runs parallel to the Oconaluftee, which locals affectionally refer to as “the Luftee”—a fast-flowing freestone waterway that provides the backdrop to a mix of retail outlets, cultural attractions, and the popular Oconaluftee Islands Park. Despite the town’s name, it’s easy to forget that this is still the heart of Cherokee country, home to the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, one of three federally recognized Cherokee tribes, and a place with over 11,000 years of human history.

Cherokee life has centered around water for thousands of years. In 2015, Cherokee folklorist Barbara Duncan observed that waterways have long been a “source of drinking water and food and medicine … a way of organizing towns, travel by dugout canoe and a way of navigating, but also the source of legends about gateways to other worlds.” Accessing these gateways required attentiveness and patience—and caring for the rivers. Cherokee elder Jerry Wolfe, who held the honorific Beloved Man, reminded me of this about a decade ago. As we sat by the Luftee, Wolfe urged me to walk quietly and listen when I went hiking along the river.

Wolfe inspired me to work with members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians to learn more of this riverine history and to apply that knowledge to a digital remapping of Southern Appalachia. I started on the banks of the Luftee, a river whose proper Cherokee name is “Egwanulti,” or “by the river,” collecting stories, photos, and archival materials about place names across the states of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee. The resulting map, Cherokee Riverkeepers, shows the persistence and significance of Indigenous knowledge at a time when waterways in the region are under threat from emissions from coal-fired power plants and toxic pollutants leaching from mountaintop-removal mining sites and other industrial areas. (The website, which launched last week, is a collaboration with the Digital Humanities Institute at the University of Sheffield, with assistance from the McClung Museum at the University of Tennessee and the Tennessee State Museum in Nashville.)

Remapping is a term advanced by Mishuana Goeman, a member of the Tonawanda Band of Seneca, to describe a process that can undermine the map’s role as a tool of settler colonialism. For centuries, European colonizers created maps and charts that facilitated unsustainable resource extraction practices and human exploitation and fixed the locations of coastlines, rivers, wetlands, and Native American communities. Those maps still inform our daily lives, our road signs, Google maps, and GPS. The endurance of those fixed points and colonial naming practices belies the dynamic, constant movement of the physical and spiritual worlds Indigenous people nurtured over thousands of years. Digital remapping has the potential to undo settler colonialism’s cartographic violence and provide more intimate understandings of the places threatened by the current climate emergency. It provides Native communities with an opportunity once again to reach into their rich histories and digitally re-embed Indigenous words, stories, and images in American landscapes and waterscapes as they work to build environmentally resilient futures.

Remapping a Cherokee-centric world requires us to strip back over four centuries of colonial violence, lies, and historical fictions. In the eighteenth century, for example, Anglo-American colonizers coveted control of Cherokee lands and waterways. As the most powerful Native polity in the Southeast, the Cherokees stood between settler societies along the Atlantic seaboard and those in the Ohio River Valley. When the United States emerged from the ashes of revolutionary war, political leaders set to work devising ways to dispossess sovereign peoples like the Cherokees. That work continued into the nineteenth century, culminating with the tragic era of dispossession and removal in the 1830s, including the notorious Trail of Tears.

Building a website like Cherokee Riverkeepers begins not with settler colonial sources but with Cherokee language and storytelling. Juanita Wilson, an Eastern Band citizen, told me that as a child, she “loved to watch the waters closely for signs of life.” Today, Wilson organizes Honoring Long Man, an initiative that aims to reconnect Cherokees to ancestral rivers through prayer and an annual cleanup effort. Digital mapping has the potential to complement such initiatives and to reanchor Cherokee names in their appropriate riparian context. Once situated, these names come to life with Cherokee stories—an oral archive that gives meaning to ancient town sites, a stand of river cane, or a series of rapids.

There are so many stories to relearn and remap. For instance, what do you know about the history of Chattanooga? Indigenous people called it Atla’nuwa, but by the eighteenth century the name had changed; the Cherokees referred to it as Tsatanu’gi. In the years after the American Revolution, Cherokees sought refuge from violent settlers at Tsatanu’gi. It’s unclear what these words mean, and elders have long speculated that they’re probably not of Cherokee origin. Still, the fact that these place names survived after settlers worked for centuries to destroy Native languages—after Cherokee people were sent on flatboats from the Tennessee (or “Tanasi”) River in Chattanooga to the Trail of Tears—provides an insight into the vibrant multiethnic and multilinguistic communities that Cherokees nurtured in this region.

Cherokee Riverkeepers contains scores of other stories about culturally significant riparian places. Along the Hiwassee River, near Murphy, North Carolina, is a spot known to Cherokees as Tlanus’yǐ, which translates to “the Leach Place.” At this location, Cherokee oral tradition recounts stories of a “Great Leach” residing in a subterranean river. The name, understood in this context, combines scientific insights and navigational information—the water there bubbles unpredictably and requires great care to pass—and popular lore about the underworld home of Tlanus’yǐ.

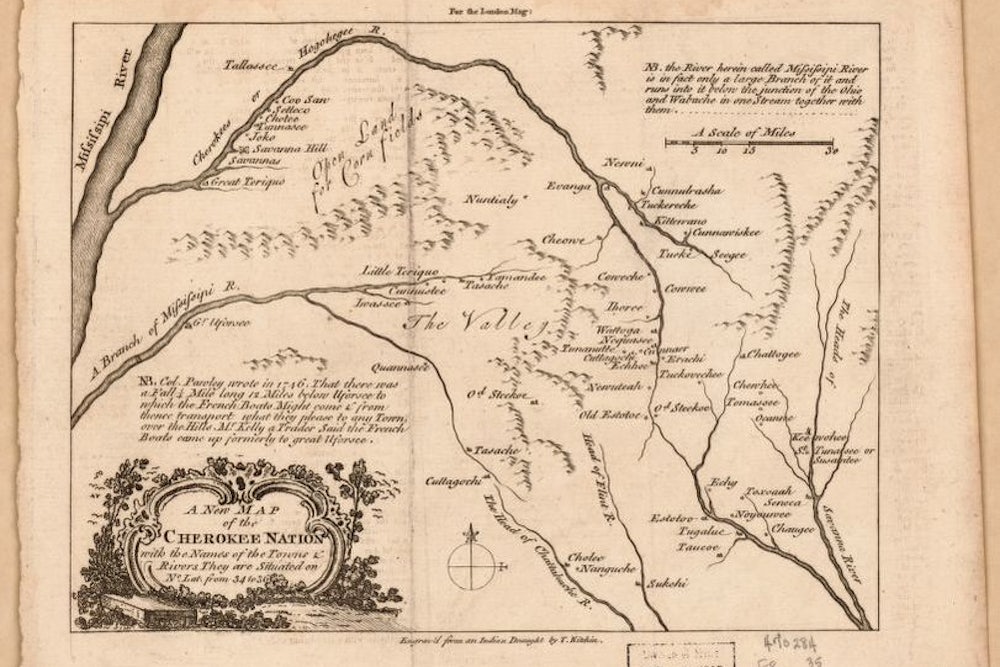

These stories are replete with lessons about human connections to local ecosystems, reminders of a place’s physical characteristics, sacred knowledge, and cartographic insights (a notched tree, a rock bearing petroglyphs). But why does any of this matter? Well, for one thing, the maps and GPS devices that we all take for granted build on colonial maps that erased Indigenous people. Quite a few of these maps, like Thomas Kitchin’s 1760 “A New Map of the Cherokee Nation,” relied extensively on Native knowledge. But when colonial officials commissioned maps, they had economic, political, and military goals in mind; Kitchin emphasized riverine navigation and trade routes to Cherokee towns at the expense of Cherokee naming practices and spiritual connections to sacred places.

Colonial maps became a technology of dispossession. Digital remapping, then, isn’t just a form of Indigenous repossession, it’s a way of showing that Native connections to landscapes and waterscapes were never eliminated by European cartographers or in the ways American officials hoped. At the same time, these new maps can undo the historical amnesia that minimizes the genocidal violence of the European and U.S. settlement and expansion. Cherokee Riverkeepers joins projects like the “Invasion of America,” by historian Claudio Saunt, and As Long as the Grass Shall Grow, which shows how Cherokee land was stolen to make Buncombe County, North Carolina.

Finally, remapping can inform today’s environmental fights. “Water is life”—from the Lakota phrase Mni Wiconi, popularized at the pipeline protests at Standing Rock—has become a yard-sign cliché, but it’s a fact that’s too often been overlooked in American history. Take the Egwanulti. As John Finger describes in his book Cherokee Americans, in the early twentieth century, a federally funded Cherokee boarding school discharged untreated waste into the river, an act of environmental vandalism that violated the Cherokees’ sacred connection to the Egwanulti. Today, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians is instituting some of the highest water quality standards in the U.S. for all of the waterways flowing through tribal lands. Michael Bolt, the head of the Eastern Band’s water quality division, told me in a Zoom conversation that “the Eastern Band made a decision to use the tools of Western science” to ensure Cherokees enjoy clean water for drinking, bathing, and sacred ceremonies. The Eastern Band’s Chief Richard Sneed has thrown the full weight of his office behind clean water initiatives. At a cleanup event for the Oconaluftee River in October 2021, Sneed reminded participants that “we come from water, and we return to water.”

When remapping Indigenous geographical traditions and environmental knowledge onto twenty-first-century landscapes and waterscapes, it’s important that non-Indigenous people resist the urge to cherry-pick Native knowledge in the hope that it will “save us” from the climate crisis or offer redemption for past wrongs. Instead, these projects are an opportunity to reflect on the importance of human and more than human relationships—the very connections that Cherokees and other Indigenous people have mapped onto the world for countless generations. Those relationships are critical to seeing the natural world as more than a site of resource extraction. They’re foundational, one elder recently told me, to saying “we’re not going anywhere” and to strengthening Indigenous sovereignty in the twenty-first century.