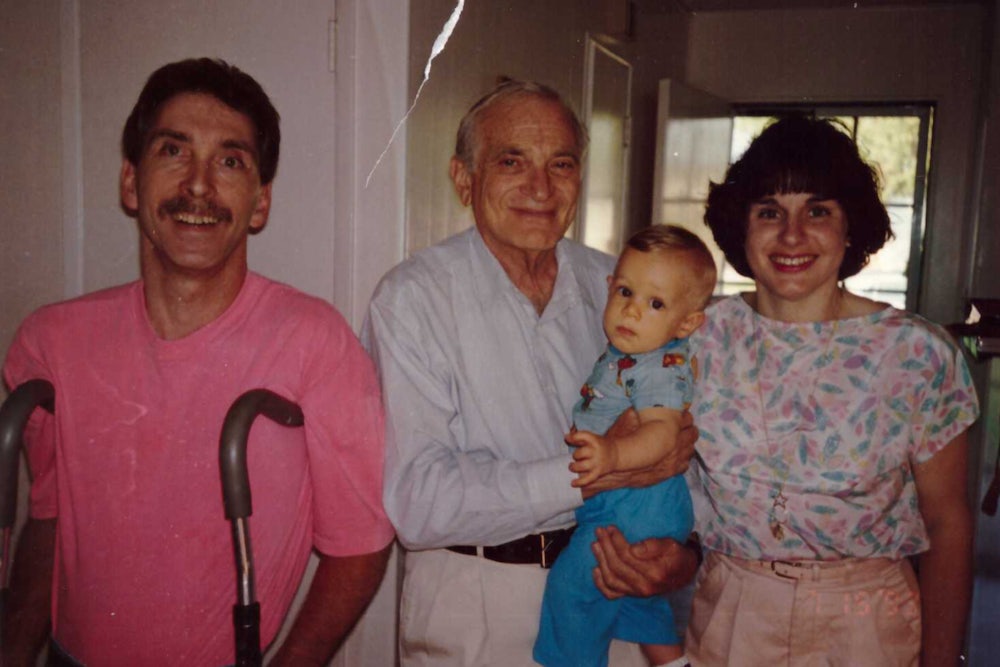

As the child of two parents with cerebral palsy, I learned at the age of six or so to offer some digestible definition of the condition to anyone who asked: It is a disorder that happens because of brain damage, usually around the time of birth. I learned the day-to-day rhythm of helping my parents: Push dad’s manual wheelchair up a restaurant’s steep switchback ramp; steady mom’s walker as she gingerly steps off a curb. It was almost fun for me, a sort of collaborative game with my parents. But as they got older, it became clear that aging meant something different for them than for most people. My mom could no longer walk unassisted after the age of 40, and by the time she was 60, she’d all but lost the ability to walk. In the span of a decade, I saw my dad use his crutches for the last time and then transition from a manual wheelchair to an electric one. None of us knew what these changes meant, nor did the doctors my parents went to.

Cerebral palsy was long thought of as something

that affected only children, something that “disappeared when you were 18. People with cerebral palsy knew that

it didn’t,” said Dr. Edward A. Hurvitz, who started his career as a pediatric

rehabilitation specialist and became interested in adults with CP as the

children he worked with grew up. “I started to look up the research on it,”

Hurvitz said, “and there was barely anything.” That’s beginning to change: The

last decade or so has seen an uptick in research about adults with CP. One of

the most important takeaways from this new body of work is the finding that health

and mobility issues

associated with CP do not stabilize—they worsen, starting in the late teens and early

twenties. Studies have highlighted that while CP is not progressive like

multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, or Alzheimer’s, its clinical

manifestations do change throughout an individual’s lifespan. Many experts have settled on describing its effects as “early aging.”

A 2016 study about exercise specifically for adults with CP—the first of its kind—suggests that an ongoing physical fitness regimen is effective in combatting this aggressive early aging, now understood to be a hallmark of CP. The finding is significant because for much of the twentieth century, the prevailing belief was that exercise was actually harmful to people with CP. Unfortunately, opportunities to apply the new knowledge about the benefits of physical activity are limited, because as CP patients grow up, intensive physical interventions become less available and less extensive. “Once you become an adult, a lot of that extra support goes away,” said Disability Rights Advocate and Consultant Anastasia Somoza. The process was similar for Grace Lapointe, a writer from Massachusetts with cerebral palsy. “Soon after I turned 18 and moved from my pediatrician to a [general practitioner], I started aging out of my CP specialists as well. They were considered pediatric.” This transition can present real problems. “They want to see a normal adult doctor, and that person has had maybe no education in what cerebral palsy actually is,” said Dr. Mark Peterson, an associate professor at the University of Michigan’s Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation.

Part of the problem for people with CP and other childhood-onset disabilities is—surprise, surprise—the way health insurance works in the United States. Peterson explained that insurance companies cover treatment based on an injury model, funding physical therapy to rehabilitate specific injuries. This model makes no sense for someone with an ongoing condition. When Lapointe switched physical therapy providers, she learned this firsthand. “The new providers evaluated me every few weeks and seemed frustrated that I was still disabled!” she told me. “They specialized in rehab for adults with temporary sports injuries, not people with permanent disabilities.” Actor and writer Marianne Leone Cooper said that she encountered the same problem with her late son, who had CP; physical therapists were always trying to “fix him,” she said, rather than understanding that the aim was about helping him live better with his disability.

This problem is not unique to CP. Nick Stary, a corrective exercise specialist at Mo-Mentum Fitness, a gym in Huntington Beach, California where my mom gets help with exercises that she’s physically unable to do alone, said that roughly 90 percent of their clientele comes in with chronic issues that didn’t heal correctly after the few physical therapy sessions they were allotted. Like my mom, they pay out of pocket for additional help. “In many ways, [the insurance companies] are penny-wise and pound-foolish,” said Hurvitz. “Giving people more accessibility—making them more participatory—is going to decrease their health care costs.” Insurance companies could do more by covering ongoing help with exercise and other treatments that could help offset the effects of CP as people age and offering consults with out-of-state specialists, since experts on the condition are few and far between. And, as many other disabled people experience, getting repairs for or replacement wheelchairs and other mobility aids can be a hassle. “I wish we had more resources for exercising safely, managing pain, and taking care of our bodies,” said Lapointe.

The federal government could also provide funding to address shortcomings in the registries that collect valuable information from volunteering individuals with CP; such data informs vital continued research on the population. There is a clinical registry for CP in the U.S. that operates by collecting data during routine clinical care, though it is fairly new and is operated by the nonprofit Cerebral Palsy Research Network rather than the federal government. The national databases and health surveys that do exist often lack necessary detail. “You can pull out people with CP from the national databases, but you can’t get enough specific information about their CP to make good clinical decisions,” said Mary Gannotti, a professor of physical therapy at the University of Hartford whose research focuses on clinical outcomes of people with chronic disabling conditions. Likewise, sorely needed is a population-based registry for CP, which would collect and record information on all the CP cases in a defined population. Population-based registries for CP already exist in countries of various income levels and in the U.S. for other lifelong conditions like spina bifida and Down syndrome. Although such a registry would entail significant startup costs, it would make CP research considerably less expensive in the long run and help fill remaining research gaps.

It often seems that CP advocacy has failed to make some of the gains that spina bifida, Down syndrome, and autism advocacy groups have, in part due to the fractured nature of the community. CP is a spectrum disorder—meaning its presentations vary widely—and advocating for such a diverse population has largely fallen on the shoulders of a handful of CP nonprofits. But there’s reason to be optimistic, as consolidation of these groups has slowly started to occur. The hope, according to Hurvitz, is that continued consolidation will lead to better governmental funding and decreased administrative costs, among other advances.

Children born today with CP will be infinitely better off than my parents were, but significant barriers remain. Almost every person with CP I’ve spoken to has had a medical professional ask them some version of, “Why aren’t you walking yet?” or “How can you still have CP as an adult?” Armed with new research about CP’s relationship to early aging—and what physical activity can do to combat it—increased focus must be placed on supporting people with CP as they transition into adulthood, and insurance companies must adopt better models for dealing with childhood-onset, lifelong disabilities. Educating practitioners and the public is a big part of that. Until adults with CP “are not an invisible population,” Gannotti said, “I don’t think they’re going to get what they need.”