On an autumn day in 2009 at the Winnebago County Courthouse in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, Ron Johnson took the stage in front of a crowd of hundreds of tea partiers. Johnson, a millionaire CEO of a successful plastics company in the state, was a political unknown. He had never run for office before and wasn’t particularly prominent in Wisconsin Republican circles. Yet here he was, sounding like a candidate and speaking alongside then–Tea Party grassroots icon Joe the Plumber.

“I’m here as a producer, and we’re under attack,” Johnson said during his speech. Johnson addressed what would become the core themes of his Senate candidacy: Democratic government would lead to the apocalypse; Obamacare is the worst single thing to ever be conceived anywhere in the universe; government spending was beyond out of control; career politicians had become the cancer killing America.

“What we don’t need is a bunch of politicians spending money they don’t have, trying to figure out new ways to tax us and, in their spare time, arrogantly attempting to take over the finest health care system in the world,” Johnson said in the same speech. “And now, in their efforts to convince us we need them to save our health care system, they are demonizing doctors and our health care providers.”

Bashing Obamacare was in high fashion among conservative grassroots and Tea Party types—and boy, did Johnson have just the story to tell. Johnson’s daughter Carey was born with a serious heart defect. She was saved by a team of doctors. His argument was that Obamacare would menace the health care system to such an extreme point that those doctors couldn’t have saved Carey if the law had been in effect. Obamacare, which was working its way through Congress at the time, “will destroy our health care system,” Johnson would tell Politico in a 2010 interview. “I am totally convinced of that.”

Spoiler alert: Obamacare didn’t wreck the American health care system. But Johnson’s spiel helped him appeal to tea partiers in Wisconsin, which helped him win the Republican nomination for Senate, putting him in an unusual spot. Johnson, a political novice, had never run for office and had few credentials and little experience—especially compared to then-Senator Russ Feingold, a 27-year veteran of Wisconsin and national Democratic politics. His speech was the beginning of a chain reaction of support. He won over radio host Charlie Sykes, who helped expand Johnson’s visibility. Then Johnson wowed activists at the state convention, which helped lead him to the nomination for a U.S. Senate seat—a rare rise for a first-time Senate aspirant.

In 2008, Obama had wiped the floor with John McCain—by 14 points. Democrat Jim Doyle was beginning his second term as Wisconsin governor. Democrats took back the state legislature as well. It seemed unthinkable that anyone short of a seasoned politician who would appeal to both moderate Republicans and Democrats could compete against let alone defeat Feingold, on most issues a crusading liberal within his party.

But this was the 2010 campaign cycle, where the Republican grassroots energy eclipsed everything else. Feingold himself would admit throughout the campaign that his chances of reelection weren’t ideal. Johnson would capitalize on that hunger among the Tea Party base, arguing that he was a “citizen legislator” who abhorred politics, rather than a career politician. When the result came in, Johnson won by just under 5 percentage points.

Johnson benefited from the Tea Party wave in that first election. Six years later, most political operatives expected Democrats to pick up Senate seats—including Johnson’s, with Feingold running to retake it—and for Hillary Clinton to become president. But Donald Trump beat Clinton in Wisconsin, and Johnson fended off Feingold, this time by 3.4 points.

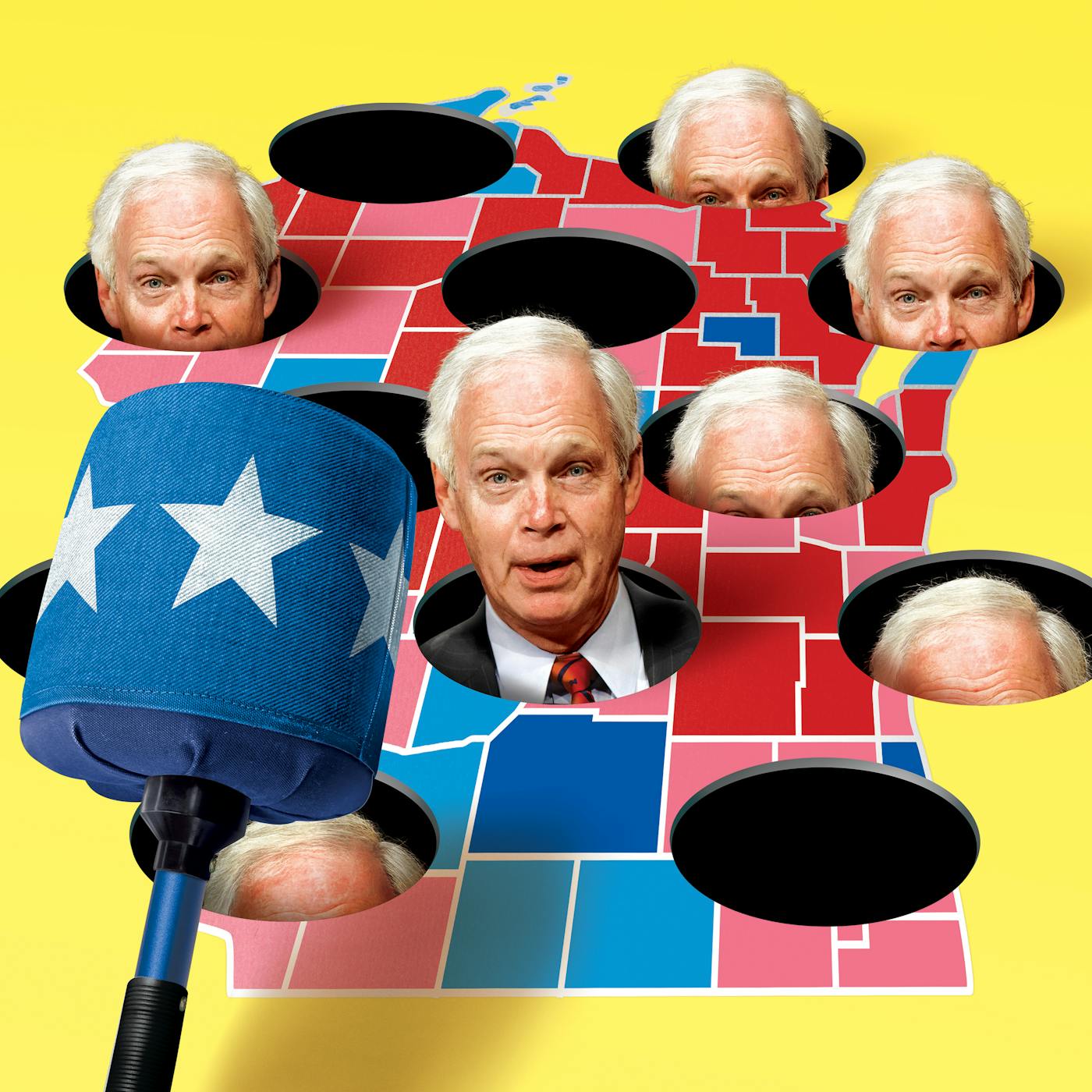

Now, 2022 is shaping up to be another good year for Republicans. Johnson has spent the last year in the Senate questioning the efficacy of vaccines amid a global pandemic, indulging in conspiracy theories about border security, and eschewing the traditional steps a candidate takes ahead of an election—as of this article’s writing, he hadn’t announced whether he would run for reelection, as most senators do.

But assuming Johnson runs, he’ll be doing so under pretty favorable conditions. Early indications are that Republicans will retake control of the House of Representatives and possibly the Senate, depending on the caliber of candidates running. True, Democrats have made gains in the state recently: Joe Biden beat Trump, they won back the governor’s mansion, and they grabbed a Senate seat now held by Senator Tammy Baldwin. But Johnson, with his wild conspiracies and constant troll-the-libs talk, is especially irksome to Democrats in Wisconsin and nationally. Indeed, it’s fair to say that, of all Senate GOP incumbents up for reelection next year, there’s none the Democrats would rather beat than Johnson.

I visited Wisconsin in early October. Driving past farms and small towns as the leaves were just beginning to turn brown and red, I saw very little hint in the bucolic scenery of the divided electorate that has driven close election outcomes and sometimes bitter political fights in the state. The current enmity goes back a decade now, to former GOP Governor Scott Walker’s contentious tenure. But the Badger State has always had a divided political soul: After archreactionary Senator Joe McCarthy died in 1957, the state’s voters elected the quite liberal William Proxmire to fill his seat.

Today, Democrats control the governor’s mansion, the lieutenant governor’s office, and the secretary of state’s office. But the GOP controls the state legislature. Robin Vos, the state Assembly speaker, has gained a level of notoriety usually reserved for firebrand federal lawmakers. His legislative identity centers on fighting just about anything and everything Governor Tony Evers does. Vos, at times, has also been the target of Donald Trump’s wrath for not indulging in the former president’s debunked conspiracy theories about the 2020 election. But at other times Vos has sought to placate the former president. In early 2021, he ordered an investigation of the 2020 election in Wisconsin and, after spending a day with Trump, promised to keep him updated on the findings.

At the same time, the state’s junior senator, Tammy Baldwin, is an ideological and temperamental opposite to Johnson. Elected in 2012, Baldwin is a former member of the Wisconsin Assembly who ran for Senate after serving seven terms in the House of Representatives. She is one of the more liberal members of the Democratic caucus. In 2019, she introduced legislation to expand Obamacare through a public option. Johnson, of course, has made a career out of warning of the perils of the health care law.

Baldwin is the first to admit, however, that her election doesn’t mean the state has any fewer Republicans. “Wisconsin is a fairly evenly divided state in statewide races,” she told me in an interview over lunch in Washington, D.C. “Wisconsin has elected Republicans and Democrats, so it becomes about, you know, turnout.”

Wisconsinites I talked to would often cite the differences between Baldwin and Johnson to illustrate the political inconsistency of the state. Sometimes it elects liberal Democrats. Sometimes it elects fire-breathing Republicans. “In statewide elections, Wisconsin can swing either way, depending on the political environment,” Scott Manley, the chief lobbyist for the Wisconsin Manufacturers & Commerce business association, told me.

If there’s any illustration that Wisconsin’s electorate is passionately divided, it’s found in how the state has handled Covid. By the beginning of December, Wisconsin was in the middle of states in terms of the percentage of the population who had been vaccinated—better than nearby states like Michigan and Ohio, but far worse than the most successful states, Vermont and Rhode Island.

That was on display during my four days there. I noticed that in Milwaukee, people wore masks inside restaurants and followed masking rules. Vos and Evers have skirmished over vaccine mandates virtually since the pandemic began. Johnson himself has helped fuel unnecessary hesitancy toward vaccinations. In mid-November, the senator’s YouTube page was, for the second time, temporarily suspended for violating the website’s rules on spreading misinformation about Covid. Johnson, who has had Covid, has been a fierce opponent of mask mandates. After he tested positive for the virus, his opposition to mask mandates did not change. He’s helped fuel skepticism nationally and within Wisconsin about Covid vaccines.

“First of all, the mounting data shows that they’re not working or are as safe as we all hoped and prayed they would be,” he said in an interview with Fox News Channel’s Maria Bartiromo in October 2021. The overwhelming evidence is that the vaccines do work, but that’s never stopped Johnson from publicly appealing to the sliver of voters who fully embrace debunked arguments on the 2020 election, immigration, and vaccinations. He’s demanded investigations into allegations of voter fraud in the 2020 election, contra other Wisconsin Republicans: Former House Speaker Paul Ryan, for example, has said Joe Biden’s win was “entirely legitimate.”

In the last few years, Wisconsin has seen contentious fights for state Supreme Court seats that have been used as tea leaves for which way the state is leaning. Republicans and Democrats lately have been in a fierce gerrymandering battle and have moved to court over the congressional maps. Nothing about this state is simply Democratic or simply Republican.

The state is also gearing up for a contentious gubernatorial election. Democratic Governor Evers won his first election in 2018 by less than 2 percentage points. This time, however, Republicans have had trouble coalescing around one candidate. Former Lieutenant Governor Rebecca Kleefisch was an early entrant into the Republican primary, under the assumption that she would run essentially unopposed. Former Vice President Mike Pence came down to meet with her at one point, a tacit sign of support. But in mid-October, Trump publicly urged former U.S. Representative Sean Duffy to run. In a statement, Trump said, “He would be fantastic! A champion athlete, Sean loves the people of Wisconsin, and would be virtually unbeatable.” Duffy was receptive and began considering it openly.

Polling shows a general dissatisfaction with the state’s top elected officials. A Marquette University Law School poll from November found Johnson’s favorability rating at 35 percent, around the lowest it’s ever been. But the poll also found Evers’s approval rating down, to 45 percent from 50 percent in August. Those numbers fall in line with a larger trend among the American electorate: dissatisfaction with the current crop of officeholders, or with inflation, or supply chains, or Covid, or all of the above.

Johnson ran as a “citizen legislator” rather than the career politician he relentlessly accused Feingold of being. But his mark as a senator has not been for any specific piece of legislation or policy brokering. Instead, it’s been his penchant for engaging in outlandish theories and fringe positions.

Even within the Republican Party, Johnson is known for his disdain for authority and the establishment. This partially stems from the final few weeks of the 2016 Wisconsin Senate race, when it seemed as if Feingold was actually going to retake his old seat. At that time, it looked as though Republicans across the country were on the verge of losing a lot of races: Hillary Clinton would win the presidential race and have a Democratic majority in the House and Senate at her back. In the final weeks of the Wisconsin Senate race, the National Republican Senatorial Committee, the campaign arm for senators, canceled $800,000 worth of advertising. Johnson had already lost some air cover from a super PAC tied to the Koch brothers canceling $2.2 million worth of ads earlier that summer. More forebodingly, polling showed Feingold beating Johnson. He was effectively left for dead by some of his allies.

“Mitch [McConnell] and him do not get along,” said Keith Gilkes, a Republican strategist who helped run Scott Walker’s presidential campaign. Gilkes compared that to Johnson’s relationship with Senator Rick Scott, the current chair of the NRSC, which is somewhat better. “Rick Scott and Ron Johnson probably can have a conversation and not hate each other,” Gilkes said.

Other fixtures within the party stepped in to help Johnson in that race. The Chamber of Commerce went back into the race with more advertising after other entities pulled out. The conservative grassroots group the Club for Growth did the same. “We helped resuscitate the campaign when the rest of D.C. said it was over in August,” a chamber official recalled.

After Johnson won, he continued to nurture a grudge against then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, technically not the head of the NRSC but effectively the final word on those decisions. Johnson has at times ticked off Republican Senate leadership since then, as when he announced he was undecided on an Obamacare repeal and replace bill. He’s also bucked his own party on an overhaul of the tax system, citing how the Senate and House versions treated certain businesses. It was just another headache from Johnson for Republican leaders.

Democratic hatred toward Johnson has nothing to do with any of that. It has mostly to do with what comes out of his mouth. Notably: After the January 6 insurrection, Johnson said he wasn’t scared by the mob, but he would have been scared if they were Black Lives Matter protesters.

“Even though those thousands of people that were marching to the Capitol were trying to pressure people like me to vote the way they wanted me to vote, I knew those were people that love this country, that truly respect law enforcement, would never do anything to break the law, and so I wasn’t concerned,” Johnson said in an interview with a local radio host. “Now, had the tables been turned—Joe, this could get me in trouble—had the tables been turned and President Trump won the election and those were tens of thousands of Black Lives Matter and antifa protesters, I might have been a little concerned.” Johnson has also hypothesized that the mob attack was fueled by “fake Trump protesters.” Similarly, he has questioned whether the FBI withheld information ahead of the attack on the Capitol. Like most other Republicans, he opposed setting up a January 6 committee to investigate the riot.

During the coronavirus pandemic, he has been one of the most high-ranking officials in Congress to elevate and push conspiracy theories about vaccines. He’s floated that Ivermectin was being suppressed in order to help boost pricier drugs with the same benefits. He’s pushed hydroxychloroquine as a viable alternative to Covid vaccines.

At the beginning of the pandemic, Johnson twice blocked proposals that would have distributed $1,200 stimulus checks to Americans. He has called climate change “bullshit.”

When he was first elected, he seemed to be just another fiscal hawk Republican. Now he’s a perfect encapsulation of the type of Republican who dives deep into misinformation and debunked science.

Generally, Republicans shrug off Johnson’s antics as his brand. “He is asking questions. He’s challenging conventional wisdom. He’s sort of out there trying to get to the bottom of things instead of just accepting what is gospel in D.C. I think that resonates at people,” said veteran strategist Gilkes.

But when pressed, Republicans privately roll their eyes at Johnson. They concede that his statements on Covid are nonsensical and dangerous, but they also see him as seeking approval mainly from the activist and oftentimes fringe base of the Republican Party.

It’s also not clear how much of what Johnson says he actually believes. After the 2020 election, while he often publicly said there were voting irregularities in his state and elsewhere that had to be investigated, he was secretly taped in August defending Joe Biden’s win in Wisconsin.

Johnson has allowed his public image to change over time. Initially, his raison d’être was that he was a ticked-off businessman worried about the deficit and governmental largesse. But more recently he’s focused on matters in which he has no professional background: the science of Covid and the pandemic, conspiracy theories about the CIA and FBI colluding to undermine Trump, and border security. On all these subjects, he’s entertained some of the most crackpot theories floating around the conservative right. In the case of Covid, doing so helps spread misinformation about vaccines and doubts about the actual available remedies to the virus. His office maintains he is not anti-vaccine; he’s just asking questions.

Johnson’s willful denial of the January 6 insurrection deserves attention, too. He’s gone beyond just downplaying it. He attempted to block Matt Graves, the Biden administration’s pick for U.S. attorney for Washington, D.C. In that role, Graves oversees prosecutions of the January 6 rioters. Johnson also used his former chairmanship at the Senate Homeland Security and Government Affairs Committee to float that the CIA and FBI could have been trying to take down President Trump. It’s not clear if Johnson was drawn to do this to keep his activist base happy or if he actually believes it. And it hardly matters. Either way, he’s playing with fire.

The field running for the Democratic nomination for Johnson’s seat is wide, but four candidates are regarded as in the top tier: Lieutenant Governor Mandela Barnes; state Treasurer Sarah Godlewski; Milwaukee Bucks senior vice president Alex Lasry; and Outagamie County Executive Tom Nelson. Then there’s a larger pool of lesser-known candidates, seven of them.

Republicans are hoping for a divided primary where all the candidates try to outflank one another by moving to the left. In the process, Republicans hope, the eventual Democratic nominee will emerge from an extended primary bruised up and poorer than might have otherwise been the case. The primary will be held on August 9, just a few months before the general election. “Regardless of whether or not Ron runs,” a veteran Republican operative with extensive campaign experience in the state told me, “whoever [the Democratic nominee is] is going to come out in August broke and bloodied up.”

Ben Wikler, the state’s current Democratic Party chairman, has been working to change that. Since he was elected to the chairmanship in 2019, part of Wikler’s vision for the state party was to ramp up its year-round organizing. “My goal was to really put jet fuel on that organizing program and expand into digital organizing and more intensive communications and to rewire our internal structure to empower staff to build a more diverse and deeper and more talented team,” Wikler explained in an interview. “We’re doing year-round voter protection work, year-round organizing work with the year-round coalitions team.”

Everyone expects the primary to be tight right up to the end. “If everyone wanted to drop out, I’d be happy for it to end now. But I would say it will probably go till August would be my guess,” Lasry predicted over lunch one day in Milwaukee. “You’re not going to see Tammy [Baldwin] or Tony [Evers] or anyone else jump in and start to try to move people. I think this is going to be a close race.”

The early days of the Senate primary have not been defined by vicious Democratic infighting. For the most part, the candidates have eyed one another and looked to peacefully garner support. Yet some identities have emerged. Barnes started out with a strong national profile, winning support from Senator Elizabeth Warren and Representative Jim Clyburn, among others. He is African American, and while Black voters are not a huge bloc in the state, they may be big enough in a Democratic primary context to make a difference. Godlewski, the state treasurer with extensive personal funds (who was unfamiliar with the common campaign parlance for fundraising when we talked), is the only woman in the top tier and has the backing of Emily’s List. Lasry, the son of billionaire Marc Lasry and a senior vice president of the Milwaukee Bucks basketball team (which his father owns), has used TV advertising earlier than the rest of the field, a sign that he plans to wage an aggressive campaign for Senate. Nelson was endorsed in November by the Sunrise Movement, the left-leaning climate change political action organization. Nelson is arguably the most liberal candidate, although in truth every candidate in this primary wants to be identified as a progressive who can get things done. Republicans are hoping the primary could pull the eventual nominee too far to the left to appeal to moderates, and that’s not an impossible situation.

If there is any uniting theme among the dozen or so candidates in the Democratic primary field, it’s in their assessment of Johnson. All argue that the key to beating Johnson is to frame him as a changed man. They say that, in the last two election cycles, Johnson won partially because he ran as an Average Joe businessman-turned-politician. He was very conservative, but his beliefs were still within the realm of reason, these Democrats argue. Now, they say, Johnson has gone off the deep end, with his outlandish claims of election fraud and the same bogeyman tactics on border security and the nonsensical imagined menace of illegal immigrants that all Trumpian Republicans love to engage in.

When I sat down with Godlewski at a coffee shop in Madison, she described the different versions of Johnson over the years. “I mean, I think that we’ve all seen that the Ron Johnson we’ve seen the last two terms in office was Ron Johnson 1.0, but more recently we’ve seen Ron Johnson 2.0, where he has been all in on Trump and things that Wisconsinites don’t even recognize,” Godlewski said. “He didn’t support the American Rescue Plan, he’s perpetuating junk science, he’s spending his Fourth of July in Russia. These are not things that Wisconsinites want their senators to be doing.”

Johnson has suggested openness to running for governor or not seeking reelection at all. But his opponents, when I interviewed them, didn’t see it. “I don’t get that he’s doing this to seek some other office at some point to raise his profile,” Barnes said. “I think he sees himself as a person who needs to go out there and quote-unquote tell the truth. I see that as a personal objective to tell people or make people think differently about things. It’s all wrong, it’s all false. It’s all steeped in something very dangerous.”

Johnson used to be viewed as a sort of “Chamber of Commerce Republican who was good on the deficit, wanted low taxes—a business guy,” Lasry said, adding, “Trump brought out his true colors.”

But painting an incumbent senator as an extremist isn’t a surefire way to oust him. Democrats saw that playbook fail in late 2021 when Virginia Democrat Terry McAuliffe tried to frame GOP opponent Glenn Youngkin as a Trump acolyte. That didn’t work, and it shows that a winning message, especially in a cycle where even weaker candidates are expected to benefit from a “red wave” of Republican victories, will have to include something beyond attacking Johnson as a hard conservative. Voters already know Johnson is an at times rebellious Republican. The case for voters to choose someone other than Johnson will have to be both a rebuke of Johnson and an alternative that appeals to Wisconsinites’ nature of picking mavericky lawmakers.

Johnson spent most of 2021 saying he was sincerely undecided about running for reelection. During his reelection campaign in 2016, he said he would serve only two terms at most. In 2021, he suggested he was leaning toward not running for a third term. But he also began saying that “political pros” have advised him that he’s well positioned to win another term.

“The fact of the matter is my preference would be to go home, but because I ran in 2010 because I was panicked for the direction of this country, a country I dearly love, I’m more panicked now,” Johnson said in November. “So the question I have going through my mind right now as I’m asking everybody else to gear up and fight to preserve this nation: Can I just leave the field and give up on the fight, go home just to protect myself, my family? I’m not sure I can do that.”

If he runs, he’ll be running in a context like that of his first race in 2010—a year when the sitting Democratic president is unpopular, and Republicans are expected to enjoy a wave election. The conservative base of the GOP is visibly energized, while Democrats fret that their base is tired and depressed. These are favorable conditions for a senator, like Johnson, who has been working to appeal to the right wing of his party.

Johnson’s chances will be even better if Wisconsin Republicans get their way in pulling off a plan, first floated around Thanksgiving by Johnson himself, that would allow Republican state lawmakers to run the state’s federal elections on their own. Under the plan, Wisconsin Republican lawmakers would take over the administration of federal elections in the state from the Wisconsin Election Commission—which itself was originally set up by Republican lawmakers—and thus be able to operate even with any intervention from Governor Evers. It’s not clear since the proposal surfaced how supportive Wisconsin Republicans are of Johnson’s plan, but it’s an ironic push for a senator whose main obsessions have been improving how elections have been conducted around the country.

Still, everyone expects the outcome to be close. That’s generally been a given in the state in recent years. Something else everyone expects is an insanely expensive race. “I’d be surprised if [the spending on] this Senate race was less than half a billion dollars,” Scott Manley, the Wisconsin lobbyist, said. “I mean I bet $500 million is probably the minimum.” That would be massive, even among the most historically expensive races. And while Manley was spitballing to an extent, his point is one shared by other operatives in both parties: The final candidates in this race won’t want for money.

To push back on arguments that Johnson has only survived in office because he ran in wave elections, Republicans point out that he outperformed Donald Trump in Wisconsin in 2016. Incumbents generally have a small cushion over a primary challenger, so it’s not unreasonable to expect Johnson to retain that support if he runs again.

In the event that it’s a bad year for Democrats, as 2022 is shaping up to be, Wisconsin doesn’t have to be a disappointment for liberals. Democrats have shown in recent years that they can win statewide offices and oust some of their most reviled opponents in the Republican Party (read: Scott Walker). Republicans will defend Johnson in a reelection campaign, but privately, some Republicans would fret only so much if he were ousted. He has managed to annoy the party’s leadership more than once.

But for Democrats the race is paramount. It could bring about a second woman senator from Wisconsin or the first African American senator from the state. It could also be the race that helps them keep control of the Senate. Where most other states have hardened their political leanings in recent years, Wisconsin remains one of the swingier ones, where a sincere progressive or fiery conservative can win without compromising principles. It’s an unusual state, one where Ron Johnson could win reelection decisively—or lose decisively.