A rash of unprecedented tornadoes ripped through the South and lower Midwest last Friday. Scientists believe there were upward of 30 tornadoes in the batch; one carved a path of 223 miles, which would be a record if confirmed. The human devastation has been unparalleled. Ninety people have been confirmed dead, dozens are missing, and thousands more have been injured—not to mention the loss of livelihoods and property.

Since the deadly twisters, there has been speculation about what created literally the perfect storm that allowed a torrent of vicious tornadoes to hit ground all at one time in mid-December. Whether or not this particular batch of tornadoes is attributable to climate change, it’s clear that the conversation about the far-reaching consequences of climate change hasn’t included the communities hit hardest by these storms. These events should force us to reconsider how we talk about climate change in—and perhaps more importantly, with—Middle America.

First, let’s consider the science about the link between climate change and tornadoes. When warm humid air rises as cool air falls inside a cloud, tornadoes can germinate inside thunderstorms. As the moving air currents pick up speed, they can go vertical and drop out of the cloud. This, of course, requires warm, humid air. Which is why anyone who’s ever lived in Tornado Alley, the swath of the South and Midwest most affected by tornadoes, knows that this is not tornado season. Rather, the bulk of tornadoes take place in the late spring and early summer.

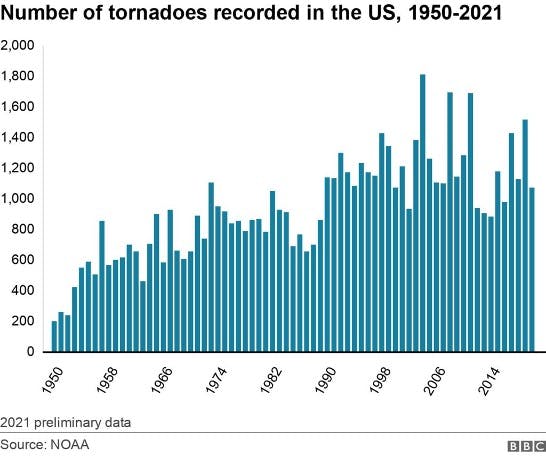

But the earth is heating, leaving Decembers warmer and wetter. And these winter tornadoes are happening more often—the five largest on record have all taken place in the last 22 years. So while it may be impossible to directly pin these tornadoes on climate change, we do know that the probability of extreme weather events—tornadoes included—will increase as the temperature rises. Indeed, the number of tornadoes that are recorded is on the rise. Though that may be, in part, a function of the ability of onlookers to document them, taken with the weekend’s turmoil, it is nonetheless ominous.

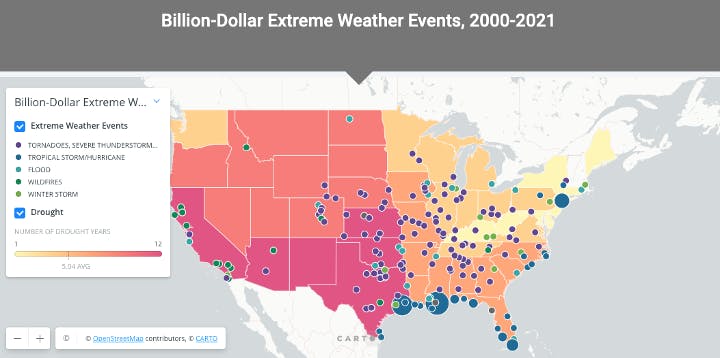

Kentucky, Southern Illinois, Missouri—these are all politically conservative red areas where climate change is unlikely to register among the top political concerns. That is, however, in part a function of how we talk about it. When we talk about climate events, we almost always highlight disasters that happen somewhere else. Hurricanes, wildfires, and receding coastlines that swallow up major metropolises—none of these sound particularly threatening to someone living in northern Kentucky. They are coastal events, a reflection of the worries that the people in coastal cities who are framing this conversation tend to focus on most.

And that’s part of the problem. Rather than a broader, more inclusive discussion about climate change, the conversation tends to exclude communities outside of liberal coastal bubbles. And then folks seem to wonder why the concern over climate change is not self-evident.

This also highlights one of the fundamental challenges of climate policy in the first place. In order to prevent unspecified outcomes that may or may not occur at some point in the near or distant future, we must take immediate, often drastic action right now. That’s a hard lift when people don’t see themselves reflected in the conversation or don’t feel themselves as being at risk.

We need to rethink how we talk about climate in two ways. First, we have to highlight the fact that the rare events we are trying to prevent can happen anywhere—and that their consequences can be broad ranging. It’s not just that climate change might increase the probability that you or a loved one could lose a life, or your home could be swallowed whole. It’s that businesses that you rely on are mowed down so often that they choose not to rebuild at all. The Center for Climate and Equity Solutions has mapped severe weather events that have cost more than $1 billion between 2000 and 2021, and a disproportionate number of them occur in traditionally red states.

But the second is more immediate. When I served as the health director for the City of Detroit, one of the overwhelming challenges with which we had to contend was the asthma epidemic among young children. Though this isn’t a direct consequence of the heating earth, it was a consequence of the means of climate change. Detroit is a heavily industrial town, and children were forced to breathe the pollution emanating from steel mills and petroleum refineries that would go on to contribute to climate change.

When I ran for office in Michigan, I learned it’s far more powerful to talk about the way our children are forced to breathe polluted air or drink polluted water than it is to talk about the distant process of climate change. Whether it’s a petroleum refinery spewing sulfur dioxide in Detroit or a concentrated animal feeding operation running ammonia into waterways in the middle of the state, focusing on the antecedents of climate change is more immediate and more tactile. It also disintermediates thorny, hard to understand scientific questions—like whether a given batch of tornadoes was the consequence of climate change.

If we are going to tackle climate change, we can’t give it half an effort. And when our engagement with the issue leaves out half our country, that’s exactly what we’re doing. Whether directly or indirectly, immediately or in some distant future, climate change will pinch all of us. Perhaps it’s worth including all of us in the discussion about how to take it on.