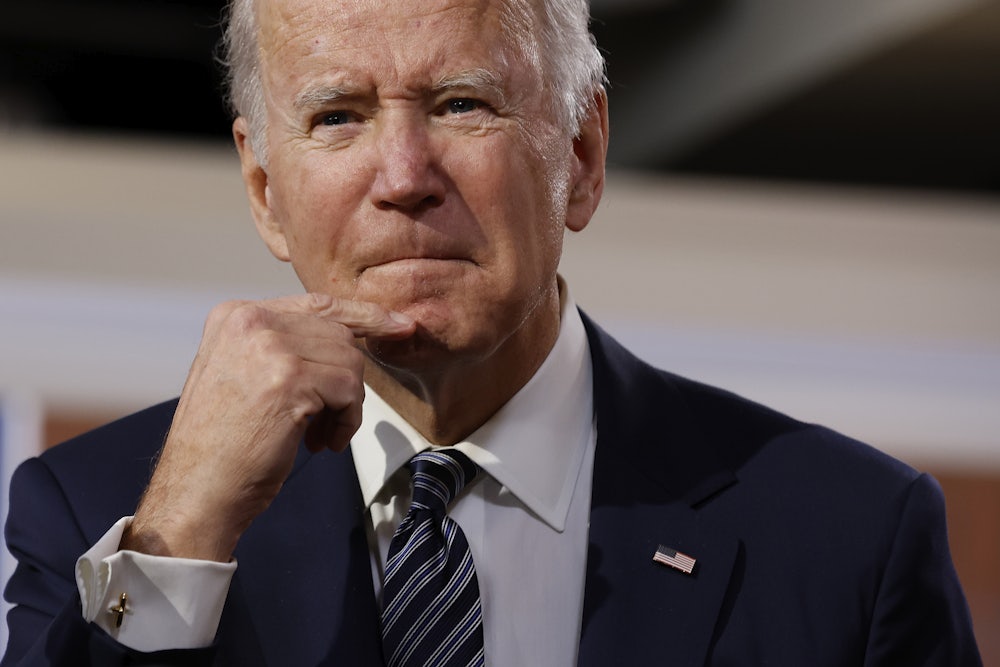

If it took President Richard Nixon to go to China, perhaps it will take President Joe Biden to begin to dismantle the legal protections that allow kleptocrats and other dubious financial actors to hide their money in the United States.

Who are these kleptocrats? Russian oligarchs. Mexican drug dealers. Saudi royal family members. Chinese Central Committee members and their children (and their sisters and their cousins and their aunts). Perhaps you read about them in the Panama Papers (2016) and the Pandora Papers (2021), two massive data leaks on shady offshore transactions. By one estimate, kleptocrats, along with terrorists and other dubious characters, engaged during the past two decades in more than $2 trillion in suspicious transactions throughout the United States. Globally, an estimated $16.3 trillion has gone missing in developing countries since 1980.

Nixon was an improbable peacemaker with the Middle Kingdom because he made his name in politics as a Red-hunter. Biden is an improbable advocate for financial transparency because he spent 36 years in the Senate representing the state of Delaware, the incorporation capital of America by dint of its see-no-evil approach to business regulation. “Look, I’m a proud capitalist,” Biden said, in January. “I spent most of my career representing the corporate state of Delaware.”

The first glimmering of a possible Nixon-to-China moment was at last week’s Summit for Democracy, where Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said: “There’s a good argument that, right now, the best place to hide and launder ill-gotten gains is actually the United States.” The Financial Times marveled that “must be a first” for a U.S. Treasury secretary. Yellen continued:

And that’s because of the way we allow people to establish shell companies. Since Andrew Jackson, individual states have been free to set their own rules for incorporating companies, and since the early 20th century, some states have allowed anybody to establish a shell company without disclosing who really owns it, what we term “the beneficial owner.” This is about to change.

“Some states” was Yellen’s euphemism for Delaware, which in 1913 displaced New Jersey as the most chartermongering state in the union, after Governor Woodrow Wilson, newly elected president, left as his parting gift to the Garden State seven antitrust statutes (“the seven sisters”) outlawing holding companies and trusts. In 2002, Jonathan Chait memorably documented Delaware’s resulting moral squalor in a New Republic story, but other states, such as South Dakota, were already gaining on the First State as havens for corporations and rich individuals, here and abroad, to hide assets from nosy government investigators.

In June, Biden issued a national security memorandum requiring the agencies to collaborate on a study examining how U.S. laws assist financial corruption. Three days before Yellen gave her remarks, the agencies delivered their report. “We will make it harder to hide the proceeds of ill-gotten wealth in opaque corporate structures,” the report said, “reduce the ability of individuals involved in corrupt acts to launder funds through anonymous purchases of U.S. real estate, and bolster asset recovery and seizure activities.” Those are just words so far, but they’re strong words.

As a down payment, Yellen announced that Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, or FinCEN, had issued a proposed regulation to build a database tracing ultimate ownership of shell companies. Under the rule, a beneficial (i.e., real) owner is defined as anyone who owns or controls 25 percent of a company or “exercises substantial control” over it.

The rule was issued under the Corporate Transparency Act, or CTA, a significant piece of anti-corruption legislation sponsored by Representative Carolyn Maloney, Democrat of New York, that became law, believe it or not, in the waning days of the Trump administration. The CTA was folded into a Pentagon spending bill that Trump vetoed because it didn’t remove social media companies’ liability protection for content posted on their sites. (He was mad at Twitter and Facebook because, after a series of escalating warnings and intermediate penalties, they were on the verge of kicking him out.) Trump’s veto message mentioned the omission of the social media provision and protested a provision in the bill that called for renaming certain military installations that were named after Confederates. The veto message made no mention of the Corporate Transparency Act. It isn’t clear Trump ever knew it was there. Congress overrode the veto.

In addition to the database rule, FinCEN also last week issued a proposed regulation under the 1970 Bank Secrecy Act requiring title companies to expand disclosure of all-cash purchases of real estate. (Current rules require disclosure only in 12 U.S. cities.) Shady real estate purchases became a source of serious embarrassment to the federal government in 2017 after a Government Accountability Office report revealed that the feds had absolutely no idea to whom they were paying rent on fully one-third of their high-security leases. In addition, the report identified 14 federal-agency tenants housed in buildings that were foreign owned; nine of the 14 agencies hadn’t known that.

Nationwide, the real estate sector is awash in dubious cash. According to an August report by the think tank Global Financial Integrity, from 2015 to 2020, $2.3 billion was laundered through real estate purchases. More than half these transactions involved “politically exposed persons” (i.e., kleptocrats).

Expect Biden’s anti-corruption campaign to stir resistance from the kleptocrat lobby. In the case of the database rule, the American Bar Association is already on record saying the Corporate Transparency Act threatens (cough, cough) “professional ethical responsibilities to their clients.” FinCEN’s real estate regulation will likely draw fire from real estate developers because the current boom in urban luxury real estate depends heavily on funny money, and a lot of those units aren’t even occupied. In his book The Wealth Hoarders, Chuck Collins cites a survey of eight luxury buildings in Boston, with condos starting at $2 million. More than 35 percent turned out to be owned by shell companies or anonymous trusts. A similar survey in Seattle found 12 percent of the units were owned by shell companies or anonymous trusts.

One way to gauge whether Biden’s crackdown on kleptocrats is effective is whether these new regulations prompt audible howls of pain from the ABA and the luxury real estate industry. If they do, great. If they don’t, we’ll know they aren’t anywhere near strong enough. Meanwhile, let’s hope many more such measures come to fruition, and soon.