For the last six weeks, graduate student workers at Columbia University have walked a picket line at the school’s Manhattan campus as they seek to negotiate a union contract that includes a living wage, better health care, and greater protections against harassment and discrimination. There has been music and dancing and marching and a giant inflatable fat cat perched atop a red car. Reports from the picket line take an overwhelming uplifting tone, and morale appears high, but this is a testament to the dedication and energy of the organizers—because the bare facts of the case are bleak. In 2014, I watched members of this union deliver a letter to the university president that asked him to voluntarily recognize their union. Now, seven years later, 3,000 members of Student Workers of Columbia are out on strike—currently the largest strike in the United States, in a year of many. That seven-year interval is a sign of the glacially paced tug-of-war that has defined the decades-long struggle of graduate employees to unionize.

These employees include graduate students who work as teaching and research assistants. In Columbia’s current union (part of UAW Local 2110), both graduate and undergraduate student workers are members of the bargaining unit. Graduate employees at public universities have long enjoyed the right to collective bargaining, but their peers at private universities, where undergraduate tuition and fees can stretch over $60,000, have seen their right to do the same fiercely debated. A long history illuminates the years of work that brought about the Columbia strike—and the ways in which the terms of the debate remain stubbornly unchanged.

In 2001, graduate employees at New York University—members of the Graduate Student Organizing Committee, or GSOC, also part of UAW Local 2110—became the first of their kind at a private university successfully to form a union and negotiate a contract with the administration. The National Labor Relations Board had ruled a year earlier that graduate teaching assistants were, in fact, employees, overturning decisions from 1972 and 1974 that stated that teaching and research assistants were primarily students, not workers protected by the National Labor Relations Act. Under the NYU contract, teaching assistants saw wages increase and working conditions improve.

The victory was short-lived: In 2004, the NLRB was leaning to the right, thanks to new appointees by President George W. Bush, and faced a decision about whether graduate employees at Brown University had the right to unionize. Graduate student workers at Brown were seeking to build on GSOC’s success, but the board sided with the university, declaring that graduate employees were not workers with collective bargaining rights. The next year, GSOC’s contract expired, and the NYU administration, citing the Brown decision as precedent, refused to negotiate a new contract.

At the same time, graduate employees at Columbia were trying to unionize. In 2002, they held a union election, but the university appealed their right to unionize to the NLRB, and the ballots were never counted.

After GSOC’s contract expired in 2005, no private university in the country recognized graduate employees as such for nearly 10 years. And yet organizing among the workers steadily increased, with union efforts continuing at NYU and Columbia, as well as at schools including Yale and Harvard. At some universities, a push for more democratic unions blossomed within those unions, as well. These caucuses, known as Academic Workers for a Democratic Union, seek to empower rank-and-file members and support struggles for social justice. At Columbia, AWDU explicitly supports movements against gentrification, anti-racist movements, and climate-justice movements, among others.

But union recognition itself still depended on legal change, which relied on the political composition of the NLRB. A bit of hope finally arrived in 2012, when the NLRB, now leaning to the left under President Barack Obama, voted to revisit the Brown decision. Graduate employees were, once again, on the verge of obtaining the legal right to unionize—and then the NYU administration preempted them. In 2013, the university offered to hold a union election without the NLRB’s involvement, conditional on GSOC withdrawing its NLRB petition to overturn the Brown decision. It was a move that puzzled some, but it benefited private universities across the country, where administrations were facing graduate employees who were ready to move forward with unionization the second they had the government’s permission to do so. GSOC and NYU reached a contract agreement in March 2015, but only after the threat of a strike.

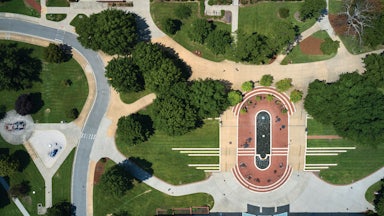

It was in the middle of this process that, in 2014, Columbia graduate employees amassed on the steps of the university’s Low Library to deliver that letter asking the school’s president to recognize their union voluntarily. Instead, the university sent the case back to the NLRB, which took the opportunity to overrule the Brown decision and expand it to cover research assistants in addition to teaching assistants, writing, “The Brown University Board’s decision … deprived an entire category of workers of the protections of the [National Labor Relations] Act.” The ruling continued, “The Brown University Board held that graduate assistants cannot be statutory employees because they ‘are primarily students and have a primarily educational, not economic, relationship with their university.’ We disagree.”

It was cause for celebration and mobilization among the teaching and research assistants who had spent years organizing for their right to collective bargaining. “It’s really exciting that they recognized that not only are grad workers workers, which is something that anyone who’s been a grad worker knows, but also that the government was willing to protect those rights,” Ian Bradley-Perrin, a union member and Ph.D. student in sociomedical sciences and history at Columbia, told me at the time.

Five years later, a contract has yet to materialize. The current strike is a renewal and expansion of the energy and optimism that the 2016 decision generated at Columbia, as well as at numerous other private universities where graduate employees had been organizing in preparation for that moment.

It has now been two full decades since GSOC, at NYU, became the first graduate employee union to sign a contract at a private university—two decades of back and forth, of legal battles, of waiting on the NLRB to flip-flop to one side or the other based on the whims of the leading political party of the day. But the union-busting tactics remain the same: Last week, Columbia threatened to replace striking union members, just as NYU once did when GSOC members went on strike in 2005.

In the last year, a wave of graduate union strikes at Columbia, NYU, and Harvard have built momentum and raised awareness. Solidarity rises, but the cyclical nature of this struggle reveals how the core arguments haven’t shifted: Universities refuse to see their workers as workers who are deserving of fair pay and working conditions, regardless of any student status they may also possess, while graduate employees contend that their work teaching undergraduates, running labs, and grading papers makes the university function and makes up a large part of the educational experience of their undergraduate students, many of whom go into significant debt to attend these prestigious universities.

Progress has been made. It shows itself in the solidarity among graduate employees and their supporters at the Columbia picket line, in the efforts not just to unionize but to make unions as democratic and responsive to rank-and-file members as possible, and in a wider political consciousness spurred on by increasing tuition, crushing student debt, subpar health care, rising costs of living, and a pandemic that has made many people feel those injustices more acutely. But when it comes to the brass tacks of the contract, the push and pull between graduate employees and private university administrations continues as it has for over 20 years.