Sharletta Evans lost her three-year-old son in a hail of bullets one torturous December evening in 1995. The Colorado mother had pulled her car up in front of a northeast Denver house, intending to dash inside to pick up her niece’s baby girl, to bring her out of harm’s way. Gunfire on the street the night before had frightened everyone in the house.

On this night, a small, white car carrying three teenagers cruised to a stop in front of the house in Park Hill, on a block scarred by violence since the mid-1980s. Two teens emerged and opened fire, spraying the house they thought was filled with rival gang members.* Little Casson Xavier, nicknamed “Biscuit,” was shot as he slept in his car seat next to his six-year-old brother. Evans cradled her toddler in her arms as he bled to death before emergency medical workers could arrive. “He took his last breath in my arms,” Evans remembered recently with painful clarity. “Still, I thought they could revive him.”

One week later, Denver police arrested a suspect. Raymond Johnson was a round-faced 15-year-old who’d grown up in half a dozen homes all over Five Points, Denver’s storied African American district. Tipped off by police, a KCNC-TV crew showed up at Raymond’s grandmother’s house to film the arrest for the nightly news. Live television cameras zoomed in on the teen, and on his white tank top, as he was handcuffed in the patrol car. He looked directly into the lens, his identity unprotected. The Denver Post quoted police describing his grandmother’s house as “heavily fortified” with steel bars and visible gang graffiti. Both the Post and the Rocky Mountain News labeled Raymond throughout his trial as “callous” and “cavalier.” The Denver public saw the young Black face of a remorseless criminal, someone who deserved a life sentence or worse.

Days later, in a whirl of grief, Evans laid eyes on Johnson for the first time, in a Denver courtroom. The prosecutor had prepared her for a stone-cold gang leader, the “worst of the worst.” The kid needed to be locked up for life, she was told, to send a message to the streets. Evans had no reason to doubt the authorities.

But Evans had heard a voice the night Casson died. It was a divine voice, she said, asking if she was prepared to forgive whoever was responsible for taking her son’s life. “Yes,” she said at the time, “I’ll forgive.”

And that day at the courtroom, she saw a child lost, shackled at the ankles. A few jheri curls strayed down Raymond’s forehead. He was alone; no apparent family in court. “I thought, oh my God, he is a little boy,” Evans said recently, her low voice rising at the distant memory. “He is nothing like they said.”

Raymond’s fractured childhood had never made the news. His father was in prison. His mother struggled with a drug addiction, ricocheting in and out of jail. At age two, he was struck by a car and suffered a severe brain injury. His grandmother raised him after the accident, but she was overwhelmed with upward of a dozen children at a time in her care. His older cousins lured him into the gang life when he was only nine years old. School failed to offer a ticket out. By age 16, Raymond was reading below a third-grade level.

The deeply spiritual Evans, even through her shattering pain, found in Raymond what the prosecutors, legislators, and compliant media were not conditioned to see—a human being capable of redemption. She knew she needed to forgive him, and the two other young suspects, in order to heal her own grief. “The media painted a picture of them, labeled them, they were throwaways,” Evans said. “And they were children.”

Johnson would be a grown man of 33 before Evans came face to face with him again in 2012, this time behind bars for a restorative justice meeting between victim and offender—the first of its kind in Colorado. They started with a prayer. Those agonizing hours sharing face-to-face convinced Evans that she was ready to accept Johnson into her family. Johnson calls her “Mother Sharletta,” his “godmother.” She unofficially adopted him. “I can honestly and truthfully say that I love this young man as my son,” Evans said. “I know that he’s better than the worst act he has committed. He’s served 25 years in prison for his crime. It’s enough punishment. He’s ready for a chance to join society.”

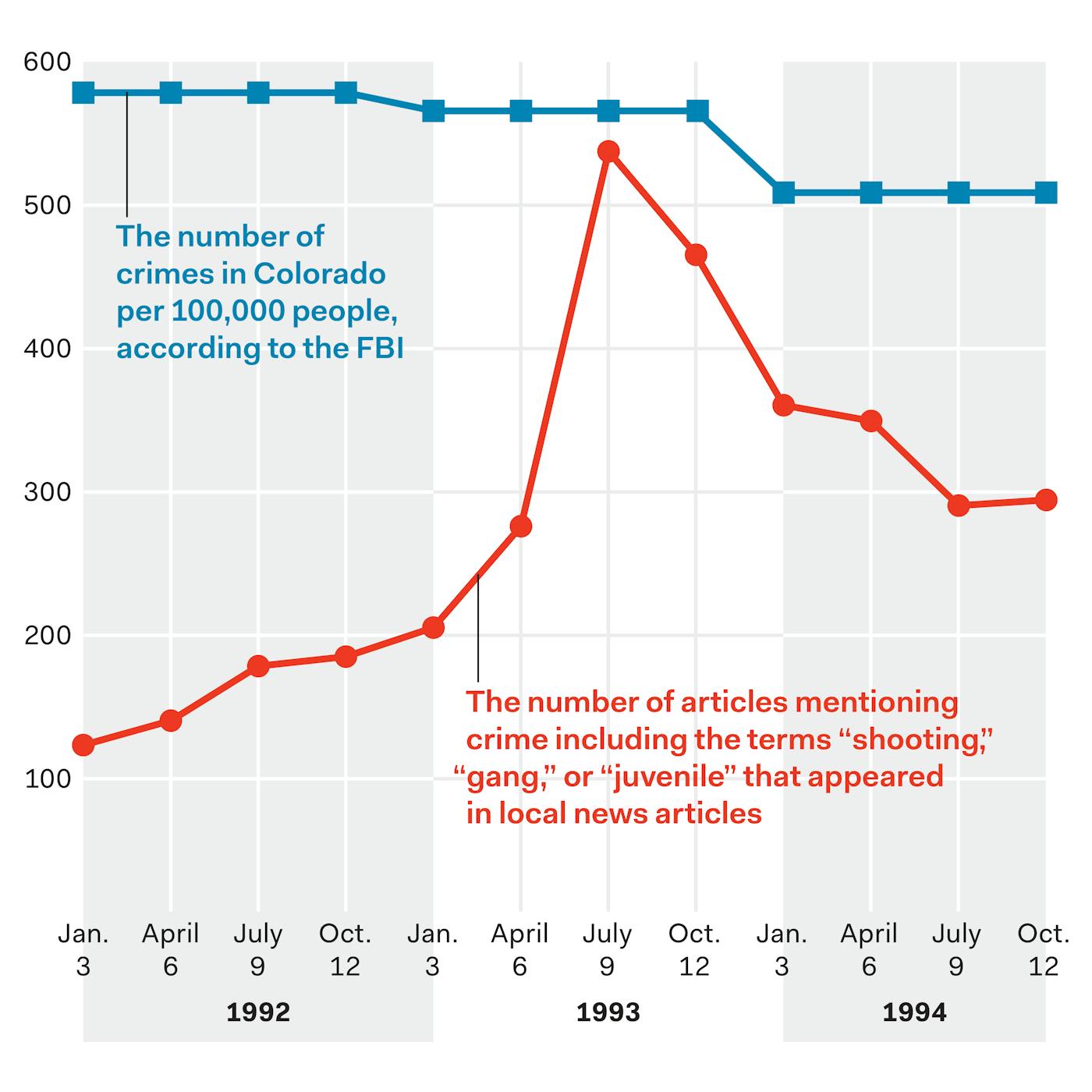

The rare relationship that evolved between a mother and her child’s killer defied the punitive justice system that Colorado legislators rushed into place after the combustible months of 1993, two years before catastrophe brought Evans and Johnson together. That was the summer of hysteria in the media about violent crime, inflated by an old-fashioned newspaper war and local TV news stations that doubled down on the dictum “if it bleeds, it leads.” The headline writers came up with a name for it: “THE SUMMER OF VIOLENCE,” splashed across front pages and TV chyrons. This, despite the reality that crime was actually a bit down from the previous summer.

“I was a product of the ‘Summer of Violence,’” Johnson said recently from Four-Mile Correctional Facility, where he has completed a reentry program for juveniles convicted as adults. He was approved for parole in June, and on November 15 the parole board told him that he would be freed from prison on early release by November 29. “The media made me into a monster. That wasn’t the case.”

Colorado is still sifting through the legal and human consequences born from that fear-stoked summer nearly three decades ago. Draconian laws were passed, creating an express lane for children into adult prisons. Those most affected were Denver’s Black youth, who made up a disproportionate share of the 46 people sentenced to life in the ’90s for crimes they committed as children. Many, like Johnson, are still behind bars. In recent years, Colorado legislators have rolled back some of the damage, bill by bill, program by program, in a halting attempt to restore juvenile rights. But they are far from done. Meanwhile, with crime again on the rise (though nowhere near the levels of the early 1990s), similar scenarios are playing out across the United States. Frenzied media coverage of violent crime has skewed public opinion and stalled judicial reforms, while the prison population continued, until recently, to soar.

The “Summer of Violence” was an overheated four months of nonstop crime coverage in 1993. The ever-pulsing drumbeat of emotional news stories about gangs and gunfire ignited public panic over a perceived wave of lethal juvenile violence. A baby grazed by a bullet in his stroller… a six-year-old shot in the head in his car… a teacher robbed and killed in a parking lot…

The incendiary season culminated in early September with Democratic Governor Roy Romer calling an emergency session of the state legislature to crack down with an “iron fist” on what he called a new breed of “amoral” youth terrorizing the city’s streets. At the time, Colorado’s century-old juvenile justice system was celebrated for its enlightened treatment of children, which emphasized rehabilitation over punishment, and protection from the adult criminal system. But in just five days’ time, lawmakers had largely dismantled it, replacing it with a system that doled out harsh adult punishments for minors.

Fear of teens and gangs had galvanized police, politicians, and editorial boards: “NO MORE MR. NICE GUY,” hailed a July 25 editorial in the Rocky, local shorthand for the Rocky Mountain News, referring to the governor’s crackdown on the city’s teens. “It’s time to strike the white flag and raise the battle standard.” “We created a bit of hysteria,” recalled Frank Scandale, then the assistant metro editor in charge of crime coverage at The Denver Post. “We got the politicians involved. There were a lot of editorials, a whole cauldron of stuff.”

The cauldron helped transform the political landscape in Colorado, laying the groundwork for a radical policy overhaul in a decade when mass incarceration was exploding across America. Both parties in Colorado united behind building more juvenile prison cells. The possibility of parole was eliminated for children as young as 14 convicted of felonies. A military-style boot camp was created for youths whom the politicians described as a new breed of hard-core criminals. Unique power was given to prosecutors to directly charge children accused of serious crimes in adult court, bypassing juvenile judges. By the end of the decade, that included lesser crimes as well. “The media blew up the homicides, blew up the gang violence,” said Maureen Cain, policy director at the Colorado State Public Defender’s Office. “The narrative in ’93 became scary kids. Scary Black kids…. We put children away for life. We locked up children until they died or were so disabled we didn’t know what to do with them. A lot of lives were lost. A lot were wasted.”

The gunfire was real that summer in Denver, each injury and death horrific. Story by story, the facts checked out, largely due to journalists’ heavy reliance on police and prosecutors. But the volume of media attention helped lead an already jittery public to believe the city was more dangerous than it was, a common reaction to fear-stoked coverage. Close analysis of Denver’s two newspapers at the time found that the scrappy Rocky Mountain News tabloid and the staid Denver Post broadsheet published 233 stories mentioning shootings in the summer of 1993, nearly 80 percent more than the previous summer when there were, in fact, more murders. The stories swirled around primarily seven high-profile crimes, all swept under a single banner, with a single narrative.

Gangs, guns, and juveniles dominated the headlines. More than 700 stories featured young gang members and shootings, more than double the number from the summer before. Juvenile crime was cited on the front page 14 times in the summer of 1993, compared with zero the prior summer. Editorials followed a similar pattern, targeting minors, even though most of the arrests that summer were of adults. Only one teen involved in a “Summer of Violence” crime ended up facing felony charges.

And here’s the thing. All the hysteria and hype notwithstanding, the facts showed that violent crime was actually declining in Colorado, and nationwide. The Denver Post’s own reporting revealed that the murder rate was down by 12 percent in 1993 since its highest point in the ’80s, when the so-called drug wars raged. The Post reported 49 homicides by August in Denver, just before the special session convened in 1993, compared with 60 by the same time a year earlier. But the facts didn’t matter. “It was 24-hour coverage. Everybody became unglued,” remembered Paul Colomy, University of Denver professor emeritus of sociology and criminology and author of a 2000 research study with Laura Ross Greiner on the media and the “Summer of Violence.” “It felt like, it sounded like, it read like Denver was facing an existential crisis perpetrated by a new breed of youthful offender.”

Some opinion leaders still contend there was, in fact, a unique crisis. “There was something going on in 1993. Whether it was inflated or blown out of proportion, it was real,” remembered John Temple, who was hired by the Rocky Mountain News in 1992 as metro editor and rose to executive editor, publisher, and president by the time the paper ultimately closed for good in 2009.

Wellington Webb, the mayor from 1991 to 2003 and Denver’s first Black chief executive, said in an interview that it was the nature of the crimes: “[They] were brazen … done in a public way, without much fear.” Governor Romer was convinced it was the character of the criminals. “These are very young people who have no code of conduct,” he told a reporter in 1993, echoing the infamous “super-predator” rhetoric coined by then-Princeton professor John DiIulio.

But the Reverend Leon Kelly, a legendary Black community activist in Denver for nearly four decades, has no doubt what tipped the scales on the summer’s news judgment. “It was the victims,” he said. Specifically, the color of the victims. Most were white. Kelly ticked off the names of four of the seven key “Summer of Violence” victims from memory. “None of them look like me,” he said. In fact, one child and all three adult victims were white. The other three victims were children aged six and younger, one Black and two Hispanic. The unflagging community organizer said he had been working since the mid-’80s to alert past governors, mayors, and news reporters to the crisis of Black and brown kids dying by gang gunfire in their segregated neighborhoods. He knew. He went to all the funerals. “We were crying for help,” said Kelly, who founded the Open Door Youth Gang Alternatives Program more than three decades ago. “Until white folks started getting hit, people weren’t coming out saying we’ve got to do something about this,” he said. Kelly has kept his own “Death List” since 1988—lives lost to gang killings. His tally shows fewer died in 1993 than the year before or the year before that.

The impact of race on story judgment was not top of mind in the mostly white Denver newsrooms that summer. “We weren’t as culturally sensitive or culturally aware, probably in large part because we weren’t as diverse as we could have been,” said Steve Lipsher, a Denver Post legislative reporter in the 1990s. Few dissenting voices made the papers. Robert Jackson, an African American reporter at the Rocky, did quote a Black business leader calling the governor’s iron-fist plan the equivalent of “cultural genocide.” That story and another airing the NAACP’s concerns about adding prison cells instead of school desks ran less than 300 words and deep inside the paper.

The power of the narrative propelled the politics. “We didn’t read statistics,” said Governor Romer, musing to a Denver Post reporter in 1998. “We read every event, and they were dramatic. It was a dramatic summer.”

The first shots that launched the summer’s frenzy were fired on May 2, 1993, outside the Denver Zoo’s polar bear exhibit. A stray bullet bounced off a guardrail, striking the forehead of 10-month-old Ignacio Fabian Pardo as he sat in his stroller.

Gun violence was hardly new to Colorado’s boom-or-bust capital at the foot of the Rocky Mountains. The Crips’ and the Bloods’ drug trade had been migrating in shifts from Los Angeles to the Mile High City since the 1980s, terrifying residents with gang-on-gang turf wars. Most of the hostilities up to then had plagued only the city’s Black and Latino neighborhoods. But rogue gunfire spilling over into its prized City Park—and a baby bloodied in an apparent shootout—rattled Denver’s core.

Both rival newspapers ran front-page versions of “GANG BULLET HITS BOY, 1, AT ZOO.” Police speculated that a nearby gun battle between warring teen gangs was the likely cause. The same day, officers rounded up three Black men—University of Colorado–Boulder football players in their twenties who happened to be in the park that afternoon. All were eventually released, but not before The Denver Post ran the young men’s photos and details of the police officers’ unfounded suspicions. “Our pictures have been all over,” complained one 22-year-old later to the Rocky Mountain News. “And I could tell you I’m innocent.”

No suspects were ever arrested. Still, the seeds of alarm were wedged into readers’ minds: Wild, violent youth seemed to be firing off guns in broad daylight, threatening ordinary Denver residents, even its littlest children. Wild West–style shootouts in the streets were not part of city leaders’ recovery plans from the 1980s oil bust that ravaged the local economy. An international airport was in the works. Coors Field Stadium was under construction, promising to revive downtown. Pope John Paul II was scheduled to lead a world youth rally in Mile High Stadium in August.

A Rocky editorial on May 5 warned of “BARBARIANS AT THE GATE” in the form of young people in “Miami-like dreads” who could be counted on to swarm the city’s zoo and scare away tourists. “The cages, after all,” mused the editorial writer, “may be housing the wrong occupants.” Little Ignacio eventually recovered, but the city’s equilibrium never did. By the end of July, the Rocky was the first to roll out the bold font banner that would define the narrative for years to come: “SUMMER OF VIOLENCE: WHEN WILL IT END?” The Post trotted out “DENVER CAUGHT IN A CROSSFIRE,” but adopted its rival’s headline one week later. Before the Rocky folded in 2009, the catchy mantra would appear 407 times in both newspapers, capturing national attention, and taking on a life of its own. Both papers, each angling to topple the other in one of the nation’s fiercest and longest newspaper wars, chased the same crimes, often using the same sources. There was a turnstile of stories on the arrests, the funerals, the town hall meetings, the court proceedings. The three local network television stations followed suit. Crime news was inescapable.

Mayor Webb responded by expanding the police gang unit, setting night curfews for teens, arming officers with more lethal weapons. Webb grew up in northeast Denver. He was not unaware that the Black community was conflicted about more police presence. Still, his efforts were applauded by the media elite. A Rocky editorial praised the mayor, dismissing concerns about potential racial discrimination in the police department. The editorial acknowledged that Denver police kept a list of suspected gang members that included more than 6,500 names, 93 percent of them kids of color. “Victim mongers may wish to focus on the trivial matter of ethnicity,” the paper wrote. “But the factor that links the members on the list is their potential criminal risk: regardless of their ethnicity, the lead in their bullets is a uniform gray.”

Webb rose to national prominence on the merits of his anti-gang response that summer. He was proudest of his prevention programs with jobs and sports, which tended to be eclipsed by the more dramatic adolescent gun control and curfew mandates. In one 24-hour period at the end of 1993, the mayor appeared on NBC’s Today, CNN’s Larry King Live, and public television’s MacNeil/Lehrer Newshour to highlight Denver’s anti-violence efforts. His influence extended to the White House. As chair of the U.S. Conference of Mayors’ Task Force on Youth Violence and Crime, Webb met with President Bill Clinton that summer. He encouraged Clinton to top his domestic agenda with a renewed war on drugs and youth crime prevention. By the end of that year, Webb’s approval rating shot up, propelling him to two more terms.

The “zoo shooting,” as it came to be known, jolted the city. But it was the bullet that hit six-year-old Broderick Bell between the eyes that brought out the full force of Denver’s media attention, firing up outrage among politicians, police, Black ministers, and the public. His mother, Ollie Marie Phason, can still recall that afternoon of June 9, 1993, in horrifying detail. Broderick’s sister was driving, and he was in the back seat. She pulled the car over to greet a friend. Three cars rolled by with teens dressed, she was told, in Crips blue. They opened fire at the houses across the street. Broderick peeked up from the back seat when a 9mm bullet blasted through the windshield and struck him in the forehead.

Every media outlet in Denver was on the story. Phason watched local television broadcasts from the waiting room at Denver General Hospital. The same image of her child smiling in his kindergarten class picture taunted her over and over. When Phason finally worked up the courage to walk into Broderick’s post-surgery recovery room, she screamed: “Bring those cameras in here! This is not the picture they’re showing on TV.”

The next day’s front-page photo of a skinny first-grader on life support, his swollen head obscured in a nest of bandages, became the iconic image for the “Summer of Violence,” the only Black victim among the high-profile crimes to come. The press chronicled every moment of Broderick’s recovery, something Phason remembers even today with gratitude.

Denver’s top officials flocked to the mother’s side in a show of political unity. Looking uncharacteristically rattled, Mayor Webb held an emotional press conference in front of Phason’s home. He declared a “war on gangs,” asking Black and Latino neighborhood residents to suspend their normal distrust of aggressive policing to end the “senselessness.” The editor of The Denver Post, the late Gil Spencer, was moved to write a personal column linking the torment he’d suffered from almost losing his own eight-year-old child to an illness to that of Broderick’s mother. “It would make some kind of sense to force-march these gang creatures into the hospital room,” Spencer wrote, “with his head still bloody, his body a forest of tubes.”

A week after the shooting, the governor, the mayor, the police chief, and district attorney linked arms with Phason for a well-publicized Juneteenth march titled “Save Our Children” and organized by the Black community. More than 1,000 supporters dressed in purple to signify the blending of the red and blue gang colors and marched to Five Points, Denver’s historic “Harlem of the West.” Phason remembered the ugly racist taunts hurled from bystanders along the way: “‘Kill each other, n-----s!’ I had never seen anything like it in all my life.” At one point, a young Crip approached her with an apology and a bouquet. “I was trembling, about to cry. I thought there could be a gun up in there,” she remembered. It was only flowers.

Like Ignacio in the zoo shooting, Broderick recovered, though he is still slightly impaired on his left side. Again, no arrests were made. Law enforcement’s failure compounded public anxiety, given the intensity of the media attention. By summer’s end, Broderick Bell’s name had appeared in 96 Denver newspaper stories, three times on the front page. By the end of 2009, Broderick’s story was mentioned 182 times and featured in eight more front-page stories. Nationally, his case was highlighted by New York Times columnist Bob Herbert in an August 1993 op-ed about the “Summer of Violence” titled “KILLING ‘JUST FOR WHATEVER.’” Denver also made CBS News’ list of the nine most violent cities in its 1995 documentary In the Killing Fields of America, produced by Dan Rather, Mike Wallace, and Ed Bradley.

By early July, Denver District Attorney Bill Ritter said he and a team of prosecutors were already urging the governor to take advantage of the media-fueled outrage to finally toughen sanctions against violent youth, changes they had wanted for a long time. Ritter, a Democrat, was savvy enough to know the summer’s crimes weren’t all juvenile-related. Still, the future governor said, “we chose to focus on juveniles because there weren’t enough consequences for violent kids.”

Five more randomly connected gun-related crimes in July and August fell under the “Summer of Violence” banner. Two Hispanic toddlers were wounded in a flurry of gunfire within 24 hours of each other. One was a three-year-old wounded in the arm by a stray bullet as he played jacks on his aunt’s porch. A 43-year-old white cable television salesman was gunned down at 4 a.m. in his car. The killing of Tom Hollar, owner of a popular clothing shop in the artsy neighborhood of Capitol Hill hit closer to home for several journalists, who happened to also live in the tony area. By the time Lori Anne Lowe, a new Denver public schoolteacher, who was white, was shot in the right side in a suburban parking lot for her purse, the public’s fears had reached a fever pitch. The only suspect was the 26-year-old driver of the getaway car that night, who is now serving a 60-year sentence. Police believed the shot that killed Lowe was fired by 16-year-old Charles Allison, who was himself killed in a gang-related shootout three weeks later.

On September 7, Colorado’s speaker of the house opened the state’s emergency session by invoking the “enormous amount” of media attention to juvenile violence in the previous six weeks. “There would not have been a special session without the media coverage,” said the University of Denver’s Colomy. “The coverage transformed the political landscape.”

The nation was in a punishing mood in the 1990s. News of a notorious, brutal gang rape of a jogger in New York City’s Central Park in 1989 ushered in the unforgiving decade. A horrified public was told by New York City media that a “wolf pack” of five Harlem teens had gone “wilding” in the park, ultimately attacking a white jogger, leaving her for dead. Their guilt was all but declared by the media—and by Donald Trump, who took out a full-page ad in four New York dailies at the time that screamed “BRING BACK THE DEATH PENALTY. BRING BACK OUR POLICE!” All five were exonerated 13 years later after the actual, lone rapist confessed. But the case helped set a tone that culminated in nearly every state passing laws making it easier to prosecute youth as adults.

Bill Clinton’s Democratic White House passed the tough 1994 crime bill, effectively wresting the tough-on-crime mantle from the Republican agenda. The law is often criticized for encouraging the U.S. explosion in prison expansion. By the end of the ’90s, the United States had quadrupled its 1970s incarceration rate. The years that followed began a slow retreat from the law-and-order ’90s, coinciding with an earlier steep drop in crime. The nation was no longer driven by what felt like a bipartisan consensus of fear. The juvenile crime rate had been on a steady decline since its peak in 1991. When the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2005 that the death penalty, and later mandatory life without parole, for kids was cruel and unusual punishment, it prompted some journalists in Denver to ask different questions, for different kinds of stories. “Once you lock these people up and throw away the key, then what happens?” asked Alan Prendergast, investigative criminal justice reporter for Westword, Denver’s alternative paper, founded in 1977.

That realization came as a career-altering jolt to Sarah Langbein (now Cohen), a young Latina Rocky Mountain News reporter, who set out to interview the 46 people still serving life sentences for crimes they committed as children—most of them in the wake of the “Summer of Violence.” These people’s lives had essentially ended before their eighteenth birthdays, leading Cohen to rethink what she was doing in journalism. She eventually left newspaper reporting altogether to become a teacher.

The Rocky published the multipart series she reported with two others, called “LIFE WITHOUT PAROLE,” in September 2005. The Denver Post followed with its own deep dive a few weeks later. “That story broke my soul in so many ways,” said Cohen, one of a few reporters of color at the Rocky in the mid-2000s. “It didn’t mean I thought all of them should be out of prison. Each case was unique. But so many had no support structures growing up.”

One of Cohen’s partners on the story, Sue Lindsay, a 32-year veteran reporter at the Rocky, remembered the experience differently. “Regardless of the tone of our series, some of these were heinous crimes. Heinous,” she said. “There was a reason why they were charged as adults.”

Racial blind spots were hard to miss. The two papers together wrote 2,515 stories by 2009 citing the 1996 unsolved murder of JonBenét Ramsey, the six-year-old beauty pageant queen and daughter of wealthy white Coloradans. A similar killing in the same period—this time of a local six-year-old Black child from Aurora—generated less than one-tenth of JonBenét’s coverage. The case, which remained unsolved for years, disappeared from the news cycle after two weeks. “Her name was Aaroné Thompson,” Cohen said. “Every time I drove through Aurora, I wondered what happened to that little girl.”

Raymond Johnson was one of the young Black men Cohen interviewed for the Rocky series in 2005. At the time, he was 26, nine years into his life sentence. “Raymond struck me as reflective about his crime,” Cohen remembered. “He was trying to turn his life over to God.”

When Johnson first entered Colorado’s Limon Correctional Facility in August 1996, he was barely literate, steeped in the gang life, serving two life sentences. Sean Taylor, a fellow inmate who became one of his older mentors in Limon, remembers Johnson’s first days. “I watched this pigeon-toed kid walk into this huge adult prison,” remembered Taylor, now the deputy executive director of Aurora’s Second Chance Center for those recently released. “He was scared. Clothes way too big.”

Several relatives incarcerated in Limon started a “tug of war for my soul,” Johnson said recently by phone from prison. Cousins on the inside pressured him to return to the gang life. Uncles urged him to join the Muslim brotherhood and improve his life. By age 19, Johnson had made his choice. “One day I woke up and said I wanted to become a Muslim,” he said. “From what I saw, they live upright and independent. I saw how they attain forgiveness in life. I wanted that.” His defection from the gang life came at a violent cost. “I have a nine-inch plate and screws in my arm from a fight,” he said. “Some family members turned their back on me. They hated me. They spit on me.”

Mentors in prison taught him to read, first by paying him $5 per chapter, then $10. He eventually earned his high school equivalency diploma, several work and life-skills certificates, and a reputation as an effective mentor in gang prevention classes.

Johnson first wrote to Sharletta Evans with his signature floral calligraphy shortly after he converted to Islam in 1999. “I asked for her forgiveness. To show her I was a changed person. I was learning,” he said. Though Evans says she had already decided to forgive him, years passed before she felt ready to respond, though her sister did on her behalf. For much of the next decade, she worked with youth in a nonprofit gang prevention group she founded. By 2009, Evans requested a reconciliation meeting with Johnson—a healing step to overcome her crush of grief. By 2012, she had submitted testimony to the U.S. Supreme Court in full support of eliminating juvenile life without parole.

That was the year Evans and her son, Calvin, 23, finally found themselves across from a 33-year-old Johnson in Limon high-security prison for a restorative justice meeting, Colorado’s first. The program had overcome years of resistance from prosecutors and victims’ rights advocates, including Evans, before it was passed into state law, spearheaded by Democratic state Senator Pete Lee.

Evans remembers her first words: “I’m Casson’s mom.” Johnson grabbed his chest and started crying uncontrollably, she said. He kept saying, “I messed up. I messed up.” Johnson told her he would spend the rest of his life trying to heal the pain he caused. The eight-hour meeting was “life-changing for the two of us,” Evans said. “We broke through hurt and pain and fears.”

Today, both wait in anxious anticipation for Johnson’s release. Eventually, they hope to write a joint book, and to do gang prevention presentations together in churches, schools, mosques, and community centers. Johnson prefers to do this work away from the cameras and journalists he learned to mistrust. “They portrayed my family as something that wasn’t worth saving,” Johnson said, of the media. “The world believed I was a monster.”

Denver’s media landscape has altered drastically since Johnson was first arrested. The 150-year-old Rocky Mountain News had shut its doors for good in 2009. The Denver Post’s newsroom staff was severely shredded by its new hedge-fund owners. Commercial television news outlets suffered similar cutbacks. Several digital start-ups, a nonprofit news site, and a robust public radio station have stepped into the local void.

The more progressive outlets have focused discussion on the punitive excesses of the past, and the legislature’s aggressive reforms. But the recent uptick in violent crime has already nudged some media into a more familiar stance. In a May editorial headlined “THE PRICE OF GOING SOFT ON CRIME,” the billionaire-owned Denver Gazette attacked the “terribly misguided” series of state justice reforms. The piece called them “a starry-eyed commitment to forgiveness, equity, ‘second chances’ ... and other buzz phrases driving the Democratic majority.”

In a Colorado State lockup, Johnson waits for that second chance to prove he is more than what the “Summer of Violence” led the Denver public to believe. “I’m grateful for the opportunity to have a home,” he said, after learning that he would be released by November 29. “I have the chance to show people who I am.”

Additional research was provided by Carroll Bogert, president of the Marshall Project, a nonprofit newsroom covering criminal justice. Data reporting was provided by Noya Kohavi and Kio Herrera, and was sponsored by a grant from the Brown Institute for Media Innovation.

* Due to an editing error, this article originally misstated that shots were fired at a car.