The Washington Free Beacon is reporting that America’s number one diet-pill enthusiast, Dr. Mehmet Oz, is exploring a run for a Pennsylvania Senate seat. As the outlet reported, though Oz was born in Cleveland, raised in Delaware, and is currently based in New Jersey, his affection for Pennsylvania appears to be primarily based in the fact that he went to school in the state 40 years ago. “Since last year, Dr. Oz has lived and voted in Pennsylvania where he attended school and has deep family ties,” a spokesperson for Oz told the Free Beacon. More likely is that Oz’s sudden affection for the state has something to do with the fact that Republican Senator Pat Toomey is retiring and, so far, the candidate pool has been rather disappointing: Oz would join the real estate developer Jeff Bartos, as well as Sean Parnell, a military veteran who is currently testifying in a child custody battle that includes allegations of physical abuse.

It is (I hope) unlikely that Dr. Oz, a well-documented purveyor of false medical claims, will sit in the Senate in 2023. But unfortunately the man who brought us such miracle cures as “rice in socks for insomnia” is pretty well suited to political campaigning, if not actually fit for office. Though Oz has most recently been associated with the Trump administration, his historical ability to blithely funnel nonsense to a dedicated audience is almost unmatched. For decades he has successfully courted the media—see this rather fawning 1995 profile in The New York Times—feted long lines of admirers, and escaped most consequential punishments for routine displays of dishonesty and corruption. In 2014, he took at least $1.2 million from pharmaceutical and medical device companies, another useful racket for a politician-to-be.

From his early days as a full-time surgeon convincing the press of the cardiac benefits of hypnosis, Oz has a particular gift for maintaining audience loyalty, even as he’s berated by the Senate for pushing “magic” diet pills with no proven benefit at all. He’s also been successful in offering vague indictments of Western medicine while encouraging private companies’ false claims, a strategy now deployed to great effect by wellness influencers and, often, anti-vaxxers across the United States. As Oz told The New Yorker just a few years ago, he yearns for the days “when our ancestors lived in small villages and there was always a healer.” Such nostalgic proclamations are often at odds with Oz’s public-facing practice, in which the “healers” are sometimes predatory businesses whose advertisements are splashed across the screen. In 2018, he settled a $5.25 million class-action lawsuit related to his boostering of bunk diet pills, without admitting fault.

According to another provider’s review of a sample of Oz’s episodes, about 78 percent of the doctor’s statements didn’t align with “evidence-based medical guidelines,” an unsurprising finding if you’re familiar with The Dr. Oz Show: The “green coffee bean extract” for weight loss; the promotion of conversion therapists as “experts”; the “conspiracy” of GMOs in food; along with more obscure and bizarre cures, such as lavender soap (for leg cramps) and raspberry ketones (“the No. 1 miracle in a bottle to burn your fat”). But following the 2016 election, like many of the tanned fixtures of daytime TV, Oz found that his particular brand of telegenic hucksterism was in high demand. Shortly before the election, he participated in a bizarre hourlong televised inspection of then-candidate Donald Trump, giving him a clean bill of health. Subsequently, Oz was appointed as health council adviser and was reported to have seriously influenced the then-president’s thinking on hydroxychloroquine, foreshadowing his career as coronavirus expert on Fox News. Last spring, Oz appeared on the network as many as four times a day.

Over the last year, perhaps in an attempt to recapture some semblance of professionalism, Oz has offered a handful of rare but reasonable opinions, among them that the Covid-19 vaccine is safe and effective and randomized trials for potential treatments are generally a good thing. That said, the doctor was also forced to apologize for suggesting it would “only cost us” 2 to 3 percent of the American population to reopen schools last spring. And like Alex Jones, he has argued, in the face of extreme criticism, that his words are entertainment rather than medical fact, telling NBC that because the “Oz” in his show’s logo is larger than “Dr.,” it’s clear his program “is not a medical show.”

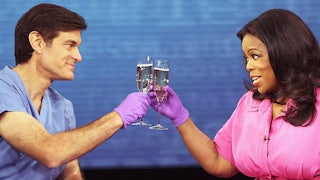

Despite all this, Oz’s show was recently renewed for a thirteenth and fourteenth season, and if his handlers are telling the truth, then someone, somewhere, gave the television personality “encouragement” to explore a Senate seat in a state to which he has tenuous ties. In the Free Beacon report, one unnamed senior Republican noted the difficulty his candidacy would face, considering the “long trail of issues that would be instant fodder for any Democrat running against him.” On the other hand, I am personally haunted by the opening paragraph of this 2013 profile, in which hundreds of people, most of them without access to regular medical care, lined up before dawn to be seen by the doctor. “I haven’t seen a doctor in eight years,” said one. “You’re the only one I trust.” And even if Oz is vastly underqualified to be a senator, the political press has a fascination with fringe candidates who sway toward the bombastic and woo-woo: Incidentally, Marianne Williamson, a Democratic contender for president fond of crystals, rose to prominence based on her appearance on Oprah, too.