The Democrats need a William Jennings Bryan. We mean the Bryan who came, full of fight, to the Democratic National Convention of 1912. He found a party threatened by resurgent Republicanism and by a rising Socialist movement, and stricken with conservatism and senility. By a single action, so simple that all could understand it, and so imperative that none could resist it, Bryan saved the Democratic Party and opened the way to the presidency of Woodrow Wilson. Bryan proposed and carried this motion:

“Resolved: That in this crisis in our party’s career and in our country’s history this convention sends greetings to the people of the United States, and assures them that the party of Jefferson and Jackson is still the champion of popular government and equality before the law. As proof of our fidelity to the people, we hereby declare ourselves opposed to the nomination of any candidate for President who is the representative of or under obligation to J. Pierpont Morgan, Thomas F. Ryan, August Belmont, or any other member of the privilege-hunting and favor-seeking class.

“Be it further resolved: That we demand the withdrawal from this convention of any delegate or delegates constituting or representing the above-named interests.”

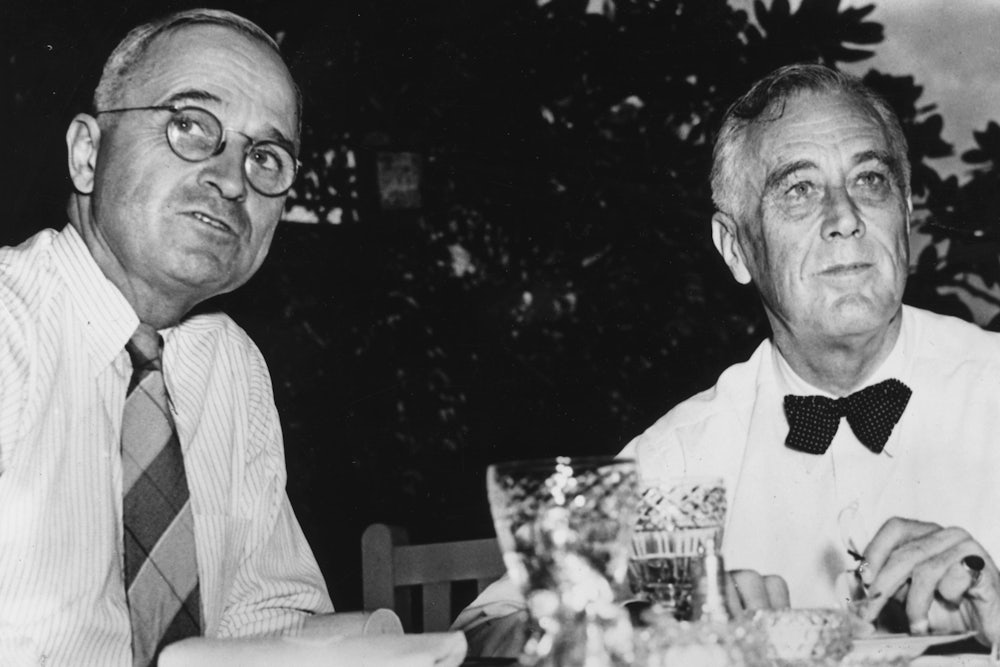

Where is the Bryan of 1948 who can rescue the Democratic Party from Wall Street domination and assure the people that the party of Jefferson and Jackson, Wilson and Roosevelt, is once again the champion of popular government and equality before the law? The crisis of his country and of his party is as urgent as in 1912. Americans are demanding the progressive leadership that alone can win lasting prosperity and peace. James Forrestal, John Snyder, George Allen and Harry Truman—the men who control the Democratic Party today—can no more provide that leadership than could their conservative counterparts whom Bryan drove from party control thirty-six years ago.

For sixteen years the Democrats have held power because Franklin Roosevelt gave the Democratic Party a progressive faith and because he taught Americans to distrust the Republican Party as the means of carrying out the will of the common man. He taught Americans to demand competence in government, and he gave them competent government.

Now, three years after his death, his legacy has been exhausted by the Truman Administration. It is the Republicans who stand for competence in government—tile central campaign issue of 1948. It is the Democrats who stand accused of incompetence. It is too late to deny the charges or to place all the blame on Congress. Every liberal Democrat knows that too many of the charges are true.

The choice for Democrats at Philadelphia is to find progressive leadership or perish.

On one side the Democrats face a revived Republican Party. Its platform is written to appeal to independents. Its new managers are master builders in organization, trained to take and to hold political power. Its nominees are strong. Both gain from impressive records, relative freedom from the actions of the 80th Congress and the ability to win important labor support by the use of a little reform and a lot of patronage.

On the other side the Democrats face the New Party. Its program is militant. Its leadership is aggressive. Its basic support is solid. History may be on its side.

“Nature abhors a vacuum,” Franklin Roosevelt told the Democratic Party in 1938, reminding it that men who fail to lead are soon replaced. The Democratic national leadership has been one immense vacuum since Roosevelt’s death.

Harry Truman and his friends have failed to act as the party in power in fighting for liberal measures. They have failed to act as the party in opposition by opposing reactionary measures pushed by Republicans. If they keep control of the Democratic Party, then the Democratic Party will be replaced as the party in power by the Republicans in November, and it will be replaced as the party in opposition by the New Party after November. The Democratic Party will perish, as it should. “The system of party responsibility in America,” Roosevelt wrote, “requires that one of its parties be the liberal party and the other the conservative party.” Fundamental in a democracy is the death and replacement of a major party which fails to lead.

No longer can the Democrats ride into power on Roosevelt’s voice and will. Yet if they fight with his legacy they can win in 1948, or lose on a principle and soon return.

Roosevelt’s legacy is clear. “My party,” he said, “can succeed only so long as it continues to be the party of militant liberalism.”

Never was the outlook brighter for such a party because never was the need greater than today: the need, that is, for a party which asserts in action the supremacy of democracy in fulfilling the needs of modern man.

The Democratic Party has never been a national party. Since the Civil War it has functioned as an emergency party, called into service only in times of crisis when the Republicans had made such a mess of things that the voters demanded a change. In the intervening years, between Cleveland and Wilson and between Wilson and Roosevelt, the party lapsed into an oldline regularity hard for even the Republicans to match.

The presidential victories won by the Democrats in the last fifty years have all been the result of a coalition of forces in the party to achieve a particular result in a particular election. Finding the right combination was always a hard task. Twice, in 1904 and 1924, the Democrats tried to win by combining the conservative South and the firmly entrenched conservative state machines, and failed. Three times in 1896, 1900, and again in 1908, they tried combining the South and the West in an openly sectional approach.

In 1912 the Democrats won with Woodrow Wilson and 44.9 percent of the total vote, only because of the split in the Republican Party. During his first term as a minority President, however, Wilson laid his plans for a broad majority combination. “Like Stephen A. Douglas,” Binkley writes in his American Political Parties, “Woodrow Wilson sought to combine the Western agrarians with Eastern labor and business, and as the standpat and the progressive factions of the Republican Party recombined he endeavored to attract the dissatisfied in elements.”

“During the war years,” Binkley continues, “President Wilson produced an almost hypnotic effect by his felicitous phrasing of the ideological common denominator of the Great Crusade, and he obtained a hitherto unknown unity that transcended party and became national.” But, the story goes on, “this unprecedented unanimity was suddenly broken by a revival of partisan strife precipitated by the President’s maladroit appeal for the election of a Democratic Congress in the term elections of 1918.”

Wilson did not live to fight day. His dream of a great national party died with the wartime coalition. Between 1920 and 1932, the elements of the old Wilson team grew and further apart. The Democrats ways had a harder time than the Republicans in sticking together because in addition to an Eastern and a Western, their party had a Southern branch. The demoralization of the party was complete when the South stubbornly rejected the hero of the Northern city Democrats, Al Smith.

Wilson’s young follower Franklin Roosevelt knew the lesson of Wilson’s 1916 triumph by heart when he began to work out a combination for his own election. His winning of the 1932 nomination by the creation of the alliance of West and South against the opposition to him which Smith organized in the East, was inspired. “His nomination,” Binkley writes, “signified that at last the party had a popular leader who united every section of his party as Cleveland, Bryan and Wilson had never quite done.”

“While no notable political leader ever came to or passed through the presidential office with an inflexible political philosophy,” Binkley continues, “it is no disparagement to say Franklin D. Roosevelt may be the inveterate opportunist of them all.” The thumbnail platform he wrote for the 1932 convention was ‘synthesized overnight out of opportunism.’ After all, it is the politician-stateman’s function to ascertain, express and translate into public policies current balance of social forces. In light of electoral verdicts, what political leader has been more successful in performing that particular function the second President Roosevelt?”

Roosevelt won four different elections by being four different men with four different campaign techniques, but always with one basic design: a coalition of the South, the big-city machines and organized labor. In 1932, when Franklin Roosevelt was less than positive in either program or leadership, the South and the powerful city machines backed him from the first, and a strong protest vote from former Republicans provided the extra strength to put him in. That really was not a Party victory. The second time, President Roosevelt ran on his record. Labor and progressives worked more actively as conservative supporters fell away, but the Democratic Party nationally was still deeply divided. The same applied in 1940 and 1944, when the campaigns were highly complicated by the crisis in Europe and our own involvement in war.

Louis M. Hacker describes the Democrats’ fundamental support after 1932 in this way:

“Previously political power had been in the hands of the middle class—the industrialists, the bankers, the large farmers. Now political power was concentrating more and more in the hands of the lower-middle class and the workers. Those who voted for Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932, 1936, 1940 and 1944 came from the smaller farms throughout the country; from the urban dwellers who toiled as workers and salaried employees; from small distributors, small manufacturers, and those on the WPA rolls.” Roosevelt and Farley tied this support into their original coalition—the South, the city machines and labor.

Except for Philadelphia in 1932 and Baltimore in 1940 and 1944, the New Deal carried all twelve of the counties which contain cities of more than half a million population (1940 census) all four times. The nine states in which these twelve cities are located have an electoral vote of 218, out of the Electoral College total of 531. The areas outside of the big cities in all of these states usually give Republican majorities, and in 1944, except for Massachusetts and California, the majority of the counties in them were Republican. The trick for the Democrats was, and is, polling a large enough total in the cities to blanket the count from the outlying regions. Every time the lesser Roosevelt politicians tended to become diverted to the minutiae of politics in the less highly populated districts, they were reminded of what areas really counted.

By paying close attention to winning the largest possible majority in the 12 great cities of the nine crucial states, Roosevelt was able to get out their marginal votes. In this way, in turn, the Democrats were able to bring out the marginal vote in border-line states and in the areas influenced by the cities.

But in every election after 1932, the Democratic Party organization concentrated not only on appealing to the labor and liberal elements in the Northern cities but to the Southern conservatives as well. “Vigor and enthusiasm” were needed from the South too, if those states were to do their share in winning over marginal votes in neighboring states. As the conflict between President Roosevelt and the Republocrats of the South grew, the Democratic majority in the “Solid South” declined. But even in 1944, when there was widespread talk of a Southwide revolt and walkout from the national party, the Democratic majority was less than 55 percent in only four of the sixteen Southern and border states.

Every Democratic victory in this century has been based on the solid electoral vote of the South. However, in terms of the popular vote, FDR could have won without the South in 1932, 1936 and even in 1940. Deducting the popular vote cast in the 16 Southern and border states from the total Democratic column in 1932, the party still had a lead of almost three million votes in the remainder of the country, a more than six-million-vote lead in 1936, just under a 700,000- vote lead in 1940. But, in 1944, even with Harry S. Truman replacing Henry A. Wallace in the interests of “party unity,” the Democratic vote would have been 714,483 votes short of the Republican, without the Southern states.

The Roosevelt-New Deal approach to party victory hinged as much on the enthusiastic support of the Solid South as on the wholehearted backing of organized labor and the machines of the big cities.

By 1938, however, the conflict between Roosevelt and the Southern reactionaries seemed intolerable to the President. It had become all too clear that government by coalition raised a basic political problem. The Administration was, by then, almost equally concerned with the problem of fascist aggression abroad and that of extending reform at home. The Southern Democrats supported the President’s position on collective security but were increasingly implacable foes of his domestic program. The Westerners supported his progressive domestic measures but at the same time clung to their isolationist views on world affairs. Only the Eastern Democrats could be depended upon to vote solidly with the President on both sets of issues. For a while the Administration managed by deftly uniting the East and the West on domestic matters and the East and the South on foreign policies. But obviously the times were too tense for such an arrangement to last.

It was than that Roosevelt determined to break with Democratic political tradition. When the Southerners refused to go along on his scheme to reorganize the Supreme Court, his Dutch was really up, and he announced his intention to “interfere” in the party primaries on the side of candidates who would loyally support the New Deal in the Congress. Jim Farley and all the professional politicians en his side were against the move. The Republicans promptly labeled it a “purge.” But the President was secure in his conviction that the time had come, not just to trade in the Walter Georges and the “Cotton Ed” Smiths for Claude Peppers and Lister Hills, though that was certainly a major political need, but to bring about a complete readjustment of party lines, fitting party labels to the ideas the politicians really stood for.

Frances Perkins, Harry Hopkins, Lowell Mellett, Henry Wallace, Tom Corcoran and Ben Cohen all encouraged the view that the time had come when the spread of organized labor into every corner of the country, and the growing unity of farmers and workers behind the New Deal program, no longer made it necessary for the Democratic Party to be intimidated by the backward elements of the South. They encouraged FDR’s thought that perhaps the New Deal might trade the Southern conservatives for Western Republican liberals who were misfits in their own party. That trade had already largely occurred in the East, led by Fiorello LaGuardia and Gifford Pinchot.

So the “purge” was on.

Roosevelt’s thinking was clear as he went into the battle, but his equipment was shoddy. The candidates with whom he proposed to rout the reactionary incumbents were, for the most part, weak reeds, unknown to him or unworthy of his personal support. The only “managers” available to run the various state campaigns were New Dealers, completely untried in political intrigue and handicapped by being regarded as “carpetbaggers” by the natives they hoped to win over to the Roosevelt side.

Most important of all, for the first time in his life President Roosevelt had adopted a tactic that was unrealistic. His campaign to defeat the reactionary Southern leaders was based on winning over a group of Southern voters, far more inclined toward Walter George than toward Franklin Roosevelt, by persuading them, on the basis of reason and self-interest, that the New Deal would benefit all groups in the South alike and would not interfere with white supremacy in the process.

Roosevelt had often tried the same line of argument on the value of reforms with the businessmen of the country. But he had certainly never depended en the “enlightenment” of those businessmen to win elections for him.

In the North, he encouraged increasing militancy on the part of the farmers and the workers to that end. In his foray into the South, he made no appeal to the poor whites and the Negroes who needed the New Deal’s help and were ready to respond. To be sure, they were in no position to turn their masters out in 1938. The Southern primary system, the poll tax, the discriminations practiced in qualifying for the vote, and the “white primary” rules, had disfranchised them. But to one of Roosevelt’s proved political acumen the procedure indicated by these facts was federal action to repeal the poll tax and otherwise break the feudal power of the primary system— not to attempt to work with the Southern opposition.

The “purge” failed. Roosevelt, like Wilson, had no second chance to rebuild his party into a modern, national structure. Having failed to best the Southerners in 1938, Roosevelt saw no choice but to capitulate in 1939. Acceptance of the Administration’s foreign policy by then seemed so imperative to the President and his closest advisers that they dared not risk its defeat by Southerners and Republicans bent on retaliation for continued domestic reforms.

In a twelve-year period, as E. E. Robinson points out in They Voted for Roosevelt, the Roosevelt leadership appealed at various times “to reformers, to radicals, to labor leaders, to businessmen, to ‘internationalists’; rarely did it appeal to all of them. At no time did it have a particular to the leaders in the area from he was seen to draw basic Democratic support, that is, from the South... Without the certainty of Southern support, Mr. Roosevelt’s programs, speeches, actions and methods of procedure in office must have been different, for in the nation outside the South he was a minority leader with temporary majority.”

Roosevelt would have understood and sympathized with this analysis of his dilemma. He recognized his major political problem and tried to do something about it at considerable personal cost to his own position. Had he lived out the war period, some of those who knew him best believe that would have tried again to turn the New Deal coalition into a national party.

Instead, the leadership of the Democratic Party passed into the hands of Harry Truman after Roosevelt’s death. Truman presented Roosevelt’s program to Congress. He watched a coalition of Northern Republicans and Southern Democrat tear that program to pieces. He gave up fighting and so lost the 1946 elections. He surrendered then to a Republican Congress. He might have used the time to direct the rebuilding of the Democratic Party. Instead, he let the Roosevelt collapse.

In the name of the bipartisan policy he sacrificed principle and failed really to fight for liberal measures. He ignored party leaders in determining policy and in appointing high officials. He alienated liberals by formulating a foreign policy of unending conflict. He made no real effort to work with labor. He let federal patronage dwindle without providing an alternative incentive. So the party faltered.

Led By Roosevelt, the coalition of the South, labor and the cities gave America a rebirth in democracy and led in the winning of a great war. It left permanent landmarks of progress such as the United Nations and the TVA. Now the coalition is breaking up.

The South is in revolt against the Democratic national leadership. Its rebellion is old and futile, since the Southerners have no place to go. Yet it is harmful. The Southern revolt may no more than 50 of the 167 votes that 16 Southern states bring to Electoral College. But, by threatening to swing these votes to a Republican candidate, some Southerners veto liberal leadership in the Democratic Party now and in the future.

By silent sabotage in the campaign, the revolt may cut down the Democratic vote in the South and the states. If labor were united in support of the Democratic Party, the loss could be borne. Today these states must be held if the Democrats are to win.

Labor has been a senior partner in the Democratic coalition since 1936. More and more the unions have turned out the city vote for which the bosses have claimed credit. Labor’s contribution in dollars and energy was decisive in Roosevelt’s last campaign.

Today the break between labor and the Truman Democrats is deep and wide. CIO-PAC officials have worked hard to draft General Eisenhower or Mr. Justice Douglas to replace Truman because they know that labor will not support the man who proposed that striking railroad workers be drafted and who subjected all government workers to a ‘’loyalty” probe.

Nineteen forty-eight was to be the year of labor action; that was the promise of all trade-union leaders who saw in the Taft-Hartley Act, and the Republican Congress which passed it, mortal threats to the continued existence of trade unionism in Amtrica. The vehicle for labor’s action in Meeting a liberal Congress was to be the Democratic Party. In many localities, labor has brought new life to the party in 1948.

But today labor is split.

Many AFL unions are traditionally Republican. Their objective is to elect a Congress that will amend the TaftHartley Act and a President who will not veto the amendment. Earl Warren has already declared his opposition to the T-H Act. Dewey may not oppose its amendment. Given a choice between Dewey and Truman, the AFL will be, at best, neutral.

Many CIO unions which in the past were most aggressive in campaigning for Roosevelt have either joined the New Party movement or will join it if Truman is nominated. These unions are among the strongest in the twelve major American cities that are vital to the Democratic Party.

Other CIO unions, if Truman is the nominee, will concentrate on local candidates. But the burden of trying to carry an unpopular national ticket is bound to make them discouraged and apathetic.

City machines, the third element in the Democratic coalition, are in bad repair. Ed Kelly and Frank Hague are tired and faltering. Ed Flynn cannot control the vote that his machine turns out on election day, and, swallowing his pride, is accepting coalition with the Republicans to withstand the Labor Party threat. Like Roosevelt, the bosses arc always inclined to cut down young leadership rather than build it up. Consequently, the men who hold the posts of district and county leaders are old and worn-out. They are crumbling under the pressure of the young and aggressive leadership of the New Party.

The morale and discipline of the city machines are breaking up. The basic supports of the machine system are rotting away. Doles and baskets have passed out of the realm of machine charity. Widows and orphans, the old and the sick have other places to turn. Fixing parking tickets, filling out immigration forms, aiding in burial services, arranging it with the judge, went out with prohibition. The unions are providing their members with the friendly services that the bosses once used to win loyalty. The needs of the people—for low-cost housing, price control, social security—are needs that the machines cannot fulfill.

Patronage, the great cementing force of all machines, is dwindling. Civil service has cut down the clerkships in the customs office that the precinct captain disposed of; inflation has shriveled up the poll watcher’s fee that gave the job of committeeman a small but adequate reward. The golden days of the city machines have vanished.

Threatened also are the assets of the party—the workers, the hard core of voters, the financial supporters— built on this loose and outworn coalition.

In 1936, 150,000 party workers organized 130,789 precinct, 3,531 county and 51 state committees for the Democratic Party. The numbers today on paper are not much less. But in place of an active army of 150,000 enthusiastic campaigners, there is often only a token force.

There are 150,000 stalwarts who contribute to the party, from the Jackson Day diners in evening dress at the Waldorf-Astoria, to the farmers in shirtsleeves at the county barbecue. But the party’s financial basis is also crumbling. In 1928 and 1932 it drew on bankers and brokers for huge contributions. By 19-40 it was relying on officeholders and organized labor to pay its bills. In 1944, hankers and manufacturers contributed more than 40 percent of Republican funds and less than 13 percent of the Democratic income. The Democrats drew from small businessmen, labor, consumer-goods producers, Hollywood, and neighborhood moving-picture theatre owners.

The Hatch Act, the Smith-Connally Act, and now the Taft-Hartley Act, all serve to cut deeply into sources of support for the Democratic Party. Funds have been available, but for a price in political corruption that the Democrats could not pay. Truman’s two-faced policy toward Israel has left the city machines high and dry. By contrast, the New Party, using aggressive fund-raising techniques, took in as much as the Democrats or the Republicans in the first six months of 1948—income which the Democrats lost.

Another dwindling asset of the Democratic Party is the hard core of regular voters. They were close to 50 percent during the New Deal. Today they are, perhaps, the 32 percent of the voters who indicated continued support of President Truman during one of his lowest periods of popularity.

Most significant, perhaps, is the loss of the spirit that distinguishes a live party. In conservative areas the Democratic spirit is drained by senility; in progressive areas, the breakaway of the New Party has caused division. Still deeper is the loss of spirit because liberals have not carried their program beyond the New Deal and given it shape and body in terms of the present needs of the American people.

To the public, the Democratic Party is its national leadership—-the President and the 45 Senators and 183 Representatives listed as Democrats in the Congress. For all the reasons given above, the national leadership is largely paralyzed. The Democrats in Congress agree on nothing, and have voted together less often than at any time since 1930.

The Democratic National Committee asserts, as it must, that Truman’s progressive proposals are killed or crippled by the Republicans in Congress; that social security, housing, price control, federal aid to education, public power, public health, progressive taxation, reclamation, reciprocal trade and adequate funds for reconstruction, have all suffered the Republican ax.

All of which is partly true. But on many occasions a majority of Democrats voted with the Republicans. Democrats combined with Republicans to override the presidential veto of the Reed-Bulwinkle bill exempting railroads from the Anti-Trust Act. They helped override the veto on a bill weakening the social-security system. Low-cost housing, picked as the number-one campaign issue by the Democrats, was bungled when 88 Democrats joined with Representative Wolcott and the real-estate lobby to support a phony housing bill. Only 85 Democrats opposed the bill. Party regularity has collapsed under Truman, with the Democrats solidly supporting their leaders little more than half of the time.

The root of this congressional evil is of course the Southern tories. Throughout the New Deal their practice of allying themselves with the most reactionary elements in the Republican Party to sabotage Roosevelt’s program constituted a dangerous threat to patty government. After the 1946 defeats, the Democrats were not only the minority party, but the Southerners were once more the predominant force within the Democratic bloc. One hundred and fourteen of 185 Democratic Representatives, and 23 of 45 Democratic Senators, were Southerners.

Truman’s recourse against the Republican majority in Congress was his veto. Taft’s counter-offensive was the organization of a two-thirds bloc of conservatives to override the veto. On vote after vote, proposals or vetoes of President Truman were killed by a coalition of Southern Democrats and Republicans.

One hundred and six Democratic Representatives voted to override the President’s veto of the Tart-Hartley Act. Seventy-one Democrats voted to sustain the President. Ninety-seven of the 106 Democrats were Southerners.

Twenty-seven Democratic Senators voted with the Republicans to override the President’s veto of the tax-reduction bill. Nineteen of the 27 were Southerners.

One hundred and one Democratic Representatives voted with the Republicans to remove thousands of workers from social-security benefits. Twenty-four Democrats opposed the measure. Eighty of the 101 were Southerners.

Ninety-four Democratic Representatives voted with the Republicans and the oil lobby to give the states control of the oil-rich tidelands; 74 of the 94 were Southerners.

The Republican Congress, committed in the main to conservative measures, was committed also to civil rights legislation in abolishing poll taxes, discrimination and lynch law. The undercover unity of the alliance was one reason why Senator Taft broke his party’s campaign pledges and refused to push legislation offensive to the Southern tories. So the American, people were beaten coming and going. They may forgive the Republicans for broken promises and double dealing. But the liberal party they will not forgive.

John Hay once called the Democratic Party “a fortuitous concourse of unrelated prejudices.” The same could be said of the Republican Party. America’s political problem as a young continent was how to combine strong central government with effective home rule in the states. America’s answer was a two-party system in which both parties, although they chose national leaders, were not national parties at all but federations of largely independent and autonomous state parties which varied greatly in character.

These state organizations, when they met in national convention, chose platforms and men acceptable to all factions. In this way, for the sake of unanimity, they often sacrificed direction and principle and sent mediocre men. to the White House because stronger men had taken sides and made enemies. Yet the federal system met the needs of a pioneer nation with as many contrasts of land, race, creed, color, religion and ways of living as mat among all the nations of Europe. It permitted all types of people to co-operate in building America.

Today the jobs of Americans are national factors through the growth of monopoly. The distance between Americans is shortened by nationwide transportation systems. The standards of Americans are fixed by national legislation. The minds of Americans are shaped by national networks of press, radio and movies. The attitudes of Americans are determined by organizations of farmers, workers business and professional groups, all active in politics. Only the political parties have failed to keep up.

A modern political party must be one—uniform in composition, continuous in structure, outspoken in principle and platform, and cohesive in character—whose policies are determined nationally and adhered to locally, and whose membership is both active and self-disciplined in accepting majority rule. This type of party alone cm survive today by providing adequate leadership.

In response to modern needs the Republican Party is becoming a national party. It was always more uniform in composition and more centralized in control than the Democratic Party. Dewey, who held his New York organization with the tightest rein, and who won the nomination by a powerful machine, is certain to modernize the party structure and reshape it into a national mold.

For the liberal party the task is always harder. The conservative party has the massed weight of the press behind it, and unlimited financial resources. It consolidates liberal reforms and stands for the status quo. Only when it commits unusual blunders and betrayals of the public interest is it endangered. But a liberal party must show the way ahead. It may gain by gathering up all the forces of discontent. But, except in moments of crisis, it cannot take power without a clear and decisive program.

As educational standards rise in America, and consciousness grows, the political awareness of Americans increases. Powerful groups of farmers, workers, Negroes, people in the professions, are not only dissatisfied with the platforms offered in past years. They are not satisfied with the rate of progress achieved. As they come to demand higher standards and faster programs, no patchwork coalition of antagonistic groups can hold them. No party today can keep within it the Southern plantation owner and the Northern Negro; the large investment banker and the CIO member; the corrupt machine boss and the ministers, the teachers, the students and veterans who are active liberals. To survive, a political party must set its course and choose its allies. They can be Philip Murray or John Rankin, but not both, if the party is to win the voters instead of fighting itself.

The New Party is founded on recognition of this truth. In accordance with modern needs, it is organizing along national lines. Its membership is disciplined and active and has provided funds as large as either major party. It demands absolute conformity of its leaders with its national policy. Its base is far too narrow for the New Party to function today as the party of militant liberalism. But where the Democratic Party shrivels up, the New Party hopes to take root and grow.

In composition a liberal party today must be based on organized labor. Only organized labor has the strength to match the force of organized capital in the industrial nation that America has become. Allied with labor are all the groups which stand for social and economic progress and which sincerely believe in civil liberties.

In structure a liberal party must give to its national committee the power to determine policy and to take measures against any rebellious minority. Its membership, as the experience of the CIO-PAC has proved, can be aroused by conviction and enthusiasm for a program rather than by increasing greed for declining patronage.

In program a modern liberal party must include in its party structure provision for adequate research and for continuous self-education of its own membership. It cannot evade issues and it cannot compromise. It must give shape in legislation to Roosevelt’s Economic Bill of Rights and to the assurance of continuing full employment. It must combat intolerance, militarization and the lack of democracy. It must ally American democracy with world democracy by demonstrating to all peoples that our purpose is to raise living standards and not armies abroad; to accept social reform and not to impose our form of capitalism; to seek cooperation with Russia without sacrificing any fundamental American principle; to give real service and not lip-service to the United Nations.

The task in every case is not simply to present the problem, as liberals have too often been content to do, but to show, at each stage of development of American and of world democracy, how the next stage can be reached.

Southern tories, Northern’ bankers, and a few aging bosses, are throttling the Democratic Party. William Jennings Bryan—here is your task.

First comes the nomination. During Harry Truman’s occupancy of the White House, the issues Roosevelt developed have been laid aside; the liberals he relied on have been driven from office, while the conservatives he held in check have taken over the government; the coalition he built has been discarded and the party he worked with has begun to fall apart. The only convincing proof that the Democrats at Philadelphia can offer of their will to survive is to nominate a liberal candidate for the presidency in place of Harry Truman.

A truly liberal candidate could reconstruct the Roosevelt coalition under progressive direction in this campaign. He could revitalize the Democratic Party, swing the labor movement into political action, assume the leadership of all progressive forces, and carry into power not only himself but enough Northern and Western liberals to enact a liberal program.

If this round is lost and Truman is renominated, the problem for the Democrats will be: how to fall without getting hurt. The question for the majority of Americans will be: can the Democratic Party be saved; is it worth saving?

A Republican landslide will leave the Democratic Party in Congress little more than the Southerners, who may make resistance to civil-rights legislation their major activity in opposition. Then liberals may work to create another party or broaden the New Party instead of narrowing the Democratic Party. America may pass through a decade like the fifties when, from a welter of Whigs, Democrats, Anti-Masons, Nullifiers, Barn-Burners, Hunkers, Loco-Focos, Cotton Whigs, Conscience Whigs and Know-Nothings, the realignment of major parties took place and the GOP emerged.

Of course a new party will appear. Changing economic and social conditions compel a changing role of government. The Republican Party is organized to resist change. As the contrast between change and resistance is compounded, disaster brings the Republicans down and carries a liberal party to power. But the task of democracy is to govern by foresight, not hindsight; to avert disaster rather than to learn from it. The question may be: will the new party be liberal and will it come in time?

The answer lies not only with the Democratic Party but with the liberal movement itself with which it is allied. Roosevelt’s success, after all, was that he served as the conductor through which the vital energy of the liberal movement flowed. Truman’s failure comes partly from his own inability, partly from the fact that the same current is not flowing today.

Today the liberal movement is without ideas. It is ignorant of its methods and uncertain of its ends. It is divided against itself, and so lacking in vision and guts that often its tune is called by the most reactionary and corrupt groups of extreme Right or extreme Left. It is weak with fear, bowed down before hysteria and filled with negative hatreds, instead of a positive and contagious faith. Unless it finds new purpose, American liberalism may be permanently lost.

Others will rise where the Republicans fall. And they must-fall. By now they have learned the lessons of the New Deal; but by now the New Deal itself is out of date. The Republicans cannot prevent a new depression or win lasting peace. Catastrophe, in depression or war, will lead to their defeat. But depression leads to war, and the cost of both is more than democracy can bear. Another such victory over the Republicans and we are all undone.

Win or lose at Philadelphia, the organization liberals choose is less important than the will they bring to the task. The job for all liberals is the same: to go through the wringer; to start at the bottom, as all great movements do, mastering the techniques and the problems of community organization; forming a full partnership with labor; training leadership in ideas, and building from local elections up; merging identities in one political organization and forcing through Congress legislation that will extend the framework of democracy to all the citizens of the South and provide for national political parties through the abolition of the archaic Electoral College and the election of our President by popular vote. Only when we build such a movement will world democracy take shape and peace be secure.