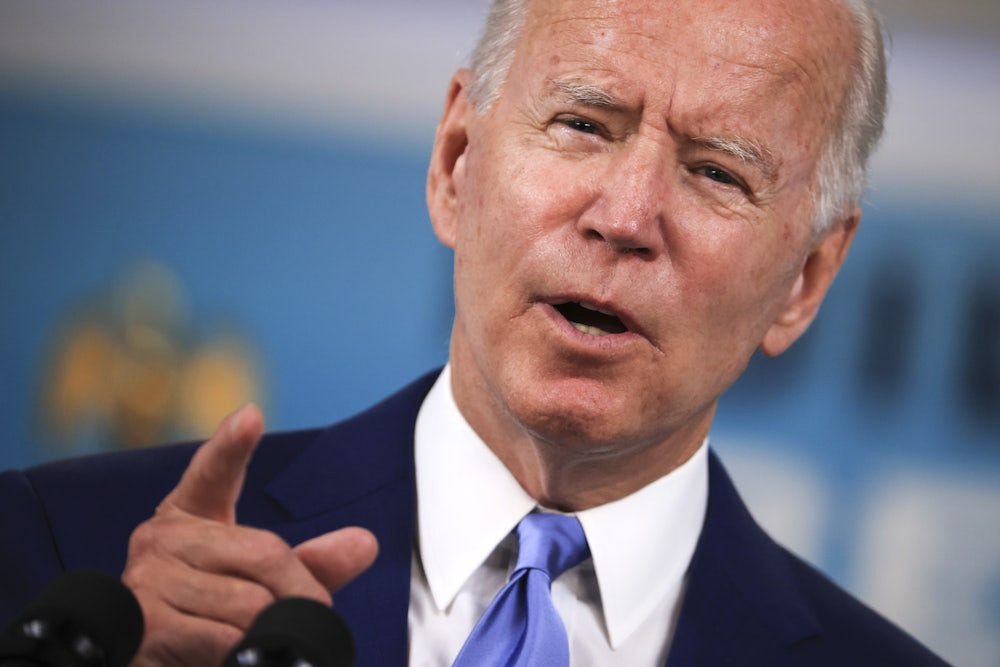

A harsh reality is setting in at the White House and Capitol Hill. One of two things needs to happen for Democrats to pass President Biden’s Build Back Better bills. Either there need to be across-the-board cuts to the spending in the $3.5 trillion reconciliation package, or specific programs need to be struck entirely. Someone is going to have to make the call about how exactly to scale back the $3.5 trillion reconciliation package, and that someone is probably going to have to be Joe Biden.

But that’s not a call that Biden is especially anxious to make—at least yet. He doesn’t want to leave any Democratic faction out in the cold. But progress appears to be slow among congressional negotiators, and the calendar is becoming a factor. And Biden is the president—and the guy who ran on being able to unite his party’s disparate factions and pass something big.

“We’re at the end of the road, and now is the moment,” said a former Democratic Senate chief of staff turned lobbyist. “It’s outside of Schumer’s hands. It’s outside of Pelosi’s hands. They need to decide what they can live with and cut a deal.”

Biden administration officials and congressional leadership know the votes aren’t there to pass the reconciliation package as it is. The progressive block in the House of Representatives don’t want to lower the top-line price tag too far down from $3.5 trillion over 10 years (although they’re aware that, realistically, it has to come down to win over some outstanding votes). They are also strongly opposed to any kind of means testing—something more conservative Democratic lawmakers, led by Senator Joe Manchin, have signaled a strong interest in. There are key lawmakers who still have problems with the package’s proposal to expand vision and dental coverage in Medicare. Maine Representative Jared Golden described it as relying on “budget gimmicks.”

Then there are the most prominent Democratic holdouts in the Senate—Manchin and Arizona Senator Kyrsten Sinema—whose hangups are at odds even with each other. Manchin doesn’t like the proposed carbon tax in the package. Sinema reportedly wants to cut spending on climate provisions but paradoxically wants the package to be robust on environmental measures, and she opposes moves to lower prescription drug prices.

That’s left top progressive negotiators exasperated and confused. It’s also helping to force Democrats to take a long hard look at their options going forward. “The time is now long overdue for Senators Manchin and Sinema to tell us exactly where they are standing,” Senator Bernie Sanders said during a conference call on Tuesday. “Do they want to cut childcare? Do they not want to negotiate with the pharmaceutical [industry] and have Medicare negotiate prescription drug prices? They don’t want paid family medical leave? They don’t want us to be aggressive in terms of climate or affordable housing or community colleges? What do they want?”

Some Democrats argue that they are fast approaching a point where the White House is going to have to make a tough call for congressional negotiators. “I think there is this frustration—or reticence—that the White House isn’t seeing us through this period,” said the former Senate Democratic chief of staff. “[Chuck] Schumer doesn’t want to be the bad cop, right? … [Nancy] Pelosi can’t do it because the vast majority of her caucus is the progressive caucus. So we’ve got this constellation of political interests.”

White House officials and those close to the negotiations say the White House isn’t quite at the point where it’s going to say time’s up for Congress and decide the next course of action. Congressional Democratic officials say right now lowering the price tag or cutting out specific proposals are both still on the table as negotiations continue. “The White House isn’t quite yet at the point where they’re going to have to decide between a “carrot” or “stick thing (yet),” one administration official said.

Speaker Pelosi, in the past few days, has offered contradictory signals on the path forward. She wrote in a letter to colleagues that it might be better if the package did “fewer things well” but then said Tuesday morning that she was “disappointed” that Congress would have to cut the overall price tag of the reconciliation bill—a move critics warn could result in underfunding every program in the package.

At the same time, though, the White House has moved to a different phase of negotiations. Susan Rice, the director of the White House’s Domestic Policy Council, has become more visible in negotiations on the Hill, oftentimes spotted going in and out of meetings with White House National Economic Council director Brian Deese. Rice, according to multiple administration officials, has been involved in the reconciliation package talks for months, and lawmakers have looked to her as one of the point people within the administration on topics that fall under the DPC’s purview: Health care, childcare, housing. Deese and Rice have been “tag teaming” those meetings, one administration official said. “It’s just that as the negotiations have come to a head, she’s become a little more visible,” the official added.

But veterans of past major Democratic policy battles warn about the limits of a White House that throws up its hands and says enough is enough. The White House has already gone out to the states, looking to rally support among the broader public by having Biden himself stump in key congressional districts. He has also used the power of the Oval Office to try to win over lawmakers like Sinema and Manchin.

“Having dealt with situations like this, there is a point where the administration really doesn’t have a lot of leverage,” said former Democratic Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle. “They can use the media. They can use the president’s Oval Office presence to bring people down and persuade as much as they can, but ultimately there isn’t a lot of leverage, and when you’re at 50–50 and almost 50–50 in the House, every person is in a position to veto a particular proposal.”

But Daschle said, so far, the White House has played its hand well in the negotiations. “I think the administration has played it about right. They’ve got to give the leaders enough flexibility,” Daschle said.

Phil Schiliro, who served as the White House director of legislative affairs during Barack Obama’s presidency, stressed that right now the White House is in the common-ground phase of negotiating with lawmakers. “It really is [about] trying to find the opportunities to reach common ground, and that’s just a process,” Schiliro said.

Still, increasingly, Democrats are having to face picking one of two choices: spending less or including fewer programs in a domestic policy package they hoped just about every Democrat running in 2022 could run on. “Here, I don’t know that there’s any magic to any number, as much as there’s getting the policies right,” Schiliro said.

Publicly, the White House is trying to exude calm. Its latest deadline for moving a package forward is still a few weeks away. White House press secretary Jen Psaki told reporters Tuesday that Biden’s role, right now, as he remains very involved in negotiations, is “to find common ground so that we can move forward with an agenda that the American people demand we pass.”

Privately, though, the White House and Washington Democrats in general know they’re fast approaching a different deadline—the moment when someone is going to have to come out and say whether to shrink the overall spending and duration of the package or include fewer programs. That is the only way for Democrats to win over the members they need to pass anything at all. The only Democrat with the necessary stature and the ear of the people who matter most to make that call is the president. Biden was the one who promised to unite as much of Congress as possible behind as large a domestic policy agenda as anyone in Washington had ever seen. Now he has to cut it.