Divinity was everywhere I looked in Mobile, Alabama. It glinted in the language used to describe the pandemic: the purgatory of its looping ebbs and flows, the perils of congregation, the miracle of vaccines, and the blind devoutness of the sheep inoculated with them. Hoping to tap its deeply religious community’s trust, Mobile County had converted some of the city’s 370-plus places of worship into vaccination clinics. Hoping to boost its health care workers’ morale, local leaders asked the houses of worship to toll their bells each day at noon for eight days of appreciation in August. Even I—a nonbeliever, and a Northerner plopped down in this Bible Belt county of 413,210 people—felt it, too, in the two nuns aboard my flight to Mobile, and the sign outside an abandoned building I kept driving by that proclaimed, ambiguously, SHIELD OF FAITH.

But alongside these spiritual symbols, I also witnessed the grotesque realities of a county battling its worst surge—more than a year and a half into the pandemic and with only about one in three residents vaccinated at the time of my visit (the number was 41 percent as of October 20). When I arrived in late August, the city’s hospitals were overrun with Covid-19 patients, too many of whom would never be discharged. In the ICUs, patients sick with the Delta variant were drowning in air and begging health care workers for vaccines. The Alabama Department of Public Health sent temporary morgue units into the area. “There’s no room to put these bodies,” an emotional Alabama state health officer, Dr. Scott Harris, told reporters at a press conference. The city’s EMS system reached a total saturation point, leading officials to urge residents to stop and consider—before they called 911—whether they really needed an ambulance. “The entire emergency medical system is overwhelmed,” Steven Millhouse, an EMT and spokesperson for Mobile Fire-Rescue, told me. “It’s just way too much.”

Early vaccine uptake had initially inspired genuine hope for the pandemic’s end. Nationwide, people rushed to stadiums, schools, mall food courts, beachfronts, banquet halls, and empty airport hangars to get their shots as soon as they could. Across Alabama, mass vaccine sites quickly hit choke points as demand outstripped the state’s supply. On March 2, Mobile County administered a record-high 4,079 doses—almost 1 percent of the county’s entire population was blessed with partial immunity in a single day. “It was steady, all day long,” Vicki Davis, a registered nurse and vaccinator with the Mobile County Health Department, told me from behind a table at All Saints Episcopal Church, where she and her colleague, another registered nurse, Adrienne Irvin, prepped for the morning’s clinic. “No matter where we were,” Irvin added, “lines.”

Then, in late spring, vaccination stalled. “It was like we reached the number of people who wanted it,” said Carolyn Eichold, a volunteer at that day’s vaccine event. By July, when a CNN crew showed up to film a vaccine pop-up at a food truck festival in Mobile, a mere 12 people got the shot—over three hours. That month, with just 34 percent of its residents inoculated, Alabama earned the undesirable distinction of being the country’s least vaccinated state (it no longer is).

“Sure, I wish we had a line out the door,” Eichold said. That morning, about two dozen people would end up trickling into All Saints. Some were regulars at the church’s weekly food share. Today, planting a seed—not harvesting by the acre—is the goal, Eichold said. “It’s a tremendous relief every time someone comes in,” she said. “I think, ‘We’ve reached somebody, and they can reach somebody.’”

At their station, Davis and Irvin prepared 30 to 40 doses of Moderna, Pfizer, and Johnson & Johnson Covid-19 shots for the morning. “If we did that many, that’s successful,” Davis said. I asked them both how they felt when they got their shots. “It brought a lot of relief,” one of them told me. The other widened her eyes and shook her head no. “I wish you wouldn’t ask me that,” she told me, returning her gaze to a paper in front of her tallying the morning’s recipients. In a few hours, bells at houses of worship would toll for exactly one minute at exactly noon. Tomorrow, Healthcare Prayer and Appreciation Week would be over. You’d have to be amid an ICU’s cacophony or close enough to a mobile morgue’s hum to hear the sound of Mobile’s everlasting Covid-19 crisis.

From the pulpit in 1882, Archdeacon Thomas Colley denounced the evils of inoculation. This “abominable mixture of corruption, the lees of human vice, and dregs of venial appetites,” he preached in a Sunday sermon entitled Vaccination: a Moral Evil; a Physical Curse; and a Psychological Wrong, “in after life may foam upon the spirit, and develop hell within, and overwhelm the soul.”

One hundred and thirty-nine years and several epidemics later, it’s salvation through injection being offered at churches throughout Mobile. In a suffocating atmosphere of distrust, public health officials need to tap into faith, wherever they find it. “Any time you’re going and doing something unknown, a house of worship is certainly a place of calm,” Davis, the nurse and vaccinator, told me. “It’s a place they know and are comfortable.”

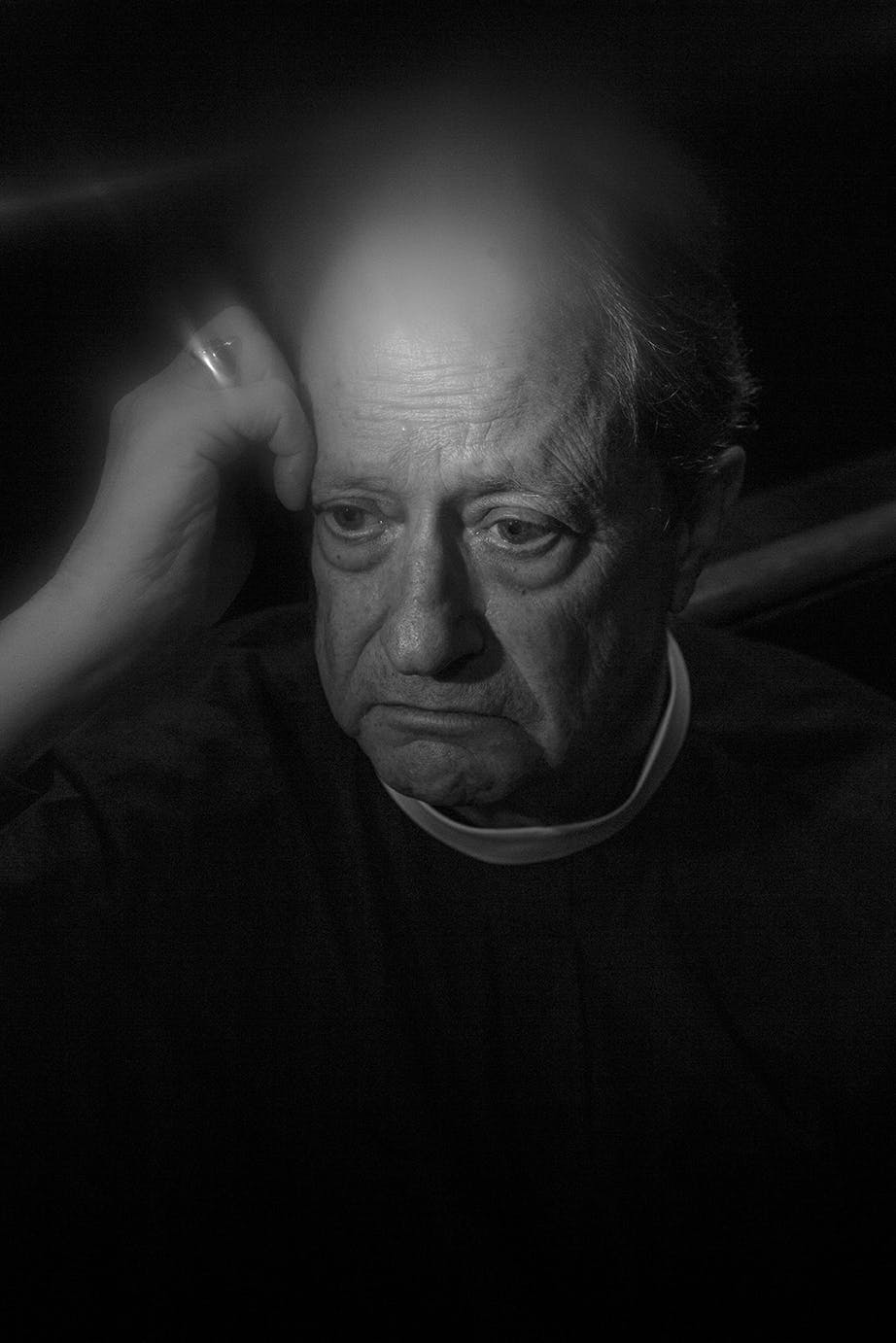

Meanwhile, beyond sanctuary, a soulish war between blind faith and grim hopelessness seemed to rage within Mobile’s vaccinated minority. Plenty of ink and pixels have been invested in their unvaccinated counterparts, and the myriad reasons—political, personal, or otherwise—for their abstention. But what, I wondered, about people living in red America who have embraced immunity? In the national battle over vaccination, their voices have largely been drowned out. Perhaps that gave them even more to say. I set out to listen—to find out what being marginalized for being vaccinated does to a person’s sense of safety, belonging, and community. They may be, statistically speaking, more sheltered from death by Covid-19, but would they ever recover from a total loss of faith in humanity? For those who have maintained compassion for vaccine holdouts or refusers, it is a mounting struggle to keep loving the neighbors who endanger by abstaining from our best tool to save ourselves. By delaying or refusing to get vaccinated against Covid-19, a majority of Alabamians have offered up their bodies to host the virus, spread its disease, and incubate its next, potentially more dangerous variant. It is a biblical question—“Am I my brother’s keeper?”—that leaves Mobile’s vaccinated sleepless by night and dread-filled by day.

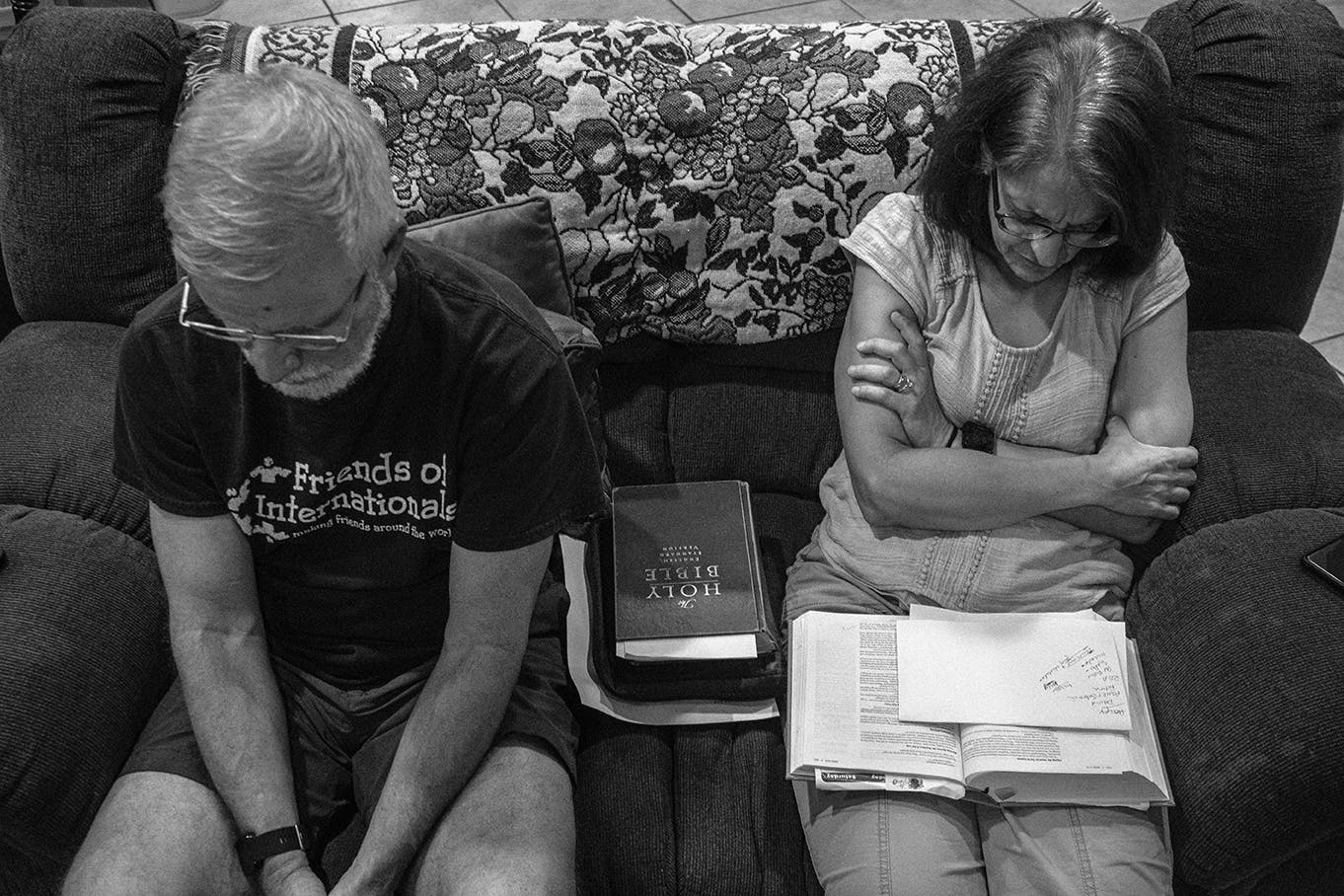

“There’s a hardening of hearts,” Pastor Jim Mather told me in the mint green living room of the home where he and his wife, Mary, run Friends of Internationals, a Christian ministry focused on international students at the University of South Alabama and the rest of the international community in Mobile. The pandemic has become more than a public health emergency. “It is a spiritual crisis,” Mather said. “We are being revealed.” It had been a shock for many to realize that mercy is not infinite, it can be drained, that there may be a hard edge to grace, and it can be reached. It was a greater shock to realize that the survival of so many in Mobile would depend on their whittled-down patience and worn-thin compassion. How else, but with open arms and hearts, could they welcome the unvaccinated majority into their outnumbered ranks? How else could they draw another soul into the sanctity of herd immunity?

“You’re tempted to be so frustrated. It breaks your heart. Like, man, this is preventable,” said Dr. Tiffani Maycock, a family doctor and vaccine hesitancy researcher at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “In the back of your mind, you know they chose not to get a vaccine. It takes a lot of discipline to not entertain that thought. I have to force myself to be empathetic.” She is not alone. Dr. Nina Ford Johnson—a pediatrician, president of the Medical Society of Mobile County, and wife of a pastor who works at a funeral home—faces Covid-19, one way or another, every day. To her dismay, many of her patients remain unvaccinated. “Maybe they don’t believe what I do or what I’m saying,” she told me. “It’s been a challenge. I do ask God, ‘Why are we going through this?’”

Even spiritual leaders have grown weary. “I have to watch myself. My patience is wearing thin,” said the Reverend Jim Flowers, All Saints pastor. “I just don’t understand it. I’m convinced there’s a segment of our population that would rather die than get vaccinated.” On a near-freezing day last January, the Reverend Joseph Laffiette eulogized and buried his younger sister, Annita, who had contracted Covid-19 in December and rapidly declined in a matter of weeks. Right after the graveside service, Laffiette got his first Covid-19 shot. “I’ve done funerals, I’ve sat with families as they cry. I understand that death is part of life,” he told me. “It’s the part where this didn’t have to happen is what gnaws at me.” If Annita would have been alive long enough to be eligible for a vaccine, he’s certain she would have gotten it. “She just didn’t have an opportunity,” Laffiette said. “Every time I see someone who refuses to be vaccinated, I think about my sister.”

And yet, for many vaccinated Mobilians I spoke to, the stakes are too high for abandonment. They had come this far. They quarantined, masked up, and got the shot to protect their communities and shield its most vulnerable members. In August, with 85 percent of hospitalized patients unvaccinated, the most endangered people in Mobile were, clearly, those who’d refused the vaccine. In their time of need—and at everyone’s most weary—whatever spare grace was left had become precious beyond measure. “I don’t know how to prevent compassion fatigue,” Maycock told me. “I just pray.” Ford Johnson, for her part, seeks patience in a biblical mantra: “With loving-kindness I have drawn thee.”

Raymond, a senior at the University of South Alabama who, like several sources I spoke to, asked me not to use his last name for privacy concerns, is not particularly religious. Instead, he turns to the myth of Tantalus, the Greek figure eternally punished to stand in a pool beneath a fruit tree in the underworld; hungry and thirsty, Tantalus cannot reach the food just beyond his grasp or the water ever beneath his reach. Like Tantalus, Raymond finds that every effort he makes is undermined. As in the underworld, relief exists only in the space beyond fingertips. It’s maddening. “You feel like you’re the odd one out, you’re the one in the wrong,” Raymond told me. “It almost feels like you’re the person spouting conspiracy theories.” In many other U.S. states at the time, he’d outnumber his unvaccinated neighbors two to one. In Alabama, it was the other way around, he said. “I’m the lunatic.”

Betty Wilkinson, a 70-year-old retired English professor living across Mobile Bay in Fairhope, Alabama, feels it as an abandonment, heavy in her chest. “It’s easy to mouth off and say, ‘Oh, those stupid people.’ But I think deeper than that, it’s scary,” she said. “It’s a paper house falling down.”

To truly believe that things could get better soon in Alabama—where, as I write this, only 37 percent of all residents are fully vaccinated, patients are being treated in hospital hallways, and too many children are on ventilators, where there is a negative number of available ICU beds, and morgues are running out of space—requires unimaginable faith. In science. In public health. In one another. “This is the great test,” Jim Mather said. “What if we fail?” I asked, somewhat desperate. “So far,” Mary replied, “we are.”

“It is difficult to breathe here,” Kevin Lee told me.

Lee, an arts editor at Mobile’s alt-weekly newspaper, Lagniappe, was mostly referring to the weather. By late morning, the temperature had already spilled over the 90-degree mark outside Soul Caffeine, a local coffee chain. With the humidity, the air feels not only hot, but viscous.

More obliquely, Lee is also describing his own respiratory problems. He was diagnosed with emphysema in 2003, when he was surprised to learn his lung capacity was one-fifth of what it should have been for his age (he is now 57). In the last 20 years, Lee has landed in the hospital a half-dozen times after the postnasal drip from a cold or seasonal allergies triggered congestion, then bronchitis and pneumonia.

Being vaccinated and immunocompromised in Mobile, Lee told me, is another kind of suffocation. Lee and his wife did what public health officials asked them to during the pandemic to slow Covid-19’s spread. They stayed in. They wore masks in public, even after Alabama’s Governor Kay Ivey lifted mandates earlier this year. In spring, once they qualified, they drove 35 minutes to a drugstore in Bayou La Batre to get their Covid-19 vaccines. At his doctor’s recommendation, Lee got his blood drawn to monitor his immunity; in September, once he was eligible, he got a booster shot.

Across the United States, more than 700,000 people and counting have died of Covid-19—more than the U.S. military casualties suffered in any war, many of which were waged for much longer than 18 months. In August alone, 284 in Mobile died of the disease—more than any other month so far in the pandemic, and representing, at the time, a staggering one-fifth of the county’s total Covid-19 death toll. Around Lee, the virus spared everyone else’s sense of normalcy. This summer, visitors and vacationers packed the beaches and bars along Alabama’s Gulf Coast, despite a mounting surge in cases and hospitalizations. The fall school semester started in-person, without statewide masking requirements. Recently, an unmasked man sat in the waiting room of Lee’s pulmonologist—a doctor whose patients are more likely than not coping with respiratory issues and are therefore uniquely vulnerable to a Covid-19 infection. “It’s astounding,” Lee said. And yet, none of it surprised him.

With our coffees long gone, a middle-aged woman sat down at the table next to us and joined the conversation. “Are you vaccinated?” Lee asked. She chuckled and told us no. When we said we both were, she gasped and, just to check, asked, “Really?” Lee asked her why she hadn’t gotten it. It wasn’t about politics, she told us. She knew people who felt worse off, health-wise, after the vaccine; she also knew people with underlying health problems who got Covid-19 and made it out fine. “I’m always a bit skeptical type of a person,” she explained. “I weighed the pros and cons and felt, for me personally, it wasn’t the right choice.” When the even-keeled conversation hit a lull, she mused out loud, “I think we’re the state with the lowest total vaccination or something.” “It’s the very bottom,” I told her. She laughed. “How is it like being in the minority in Alabama, getting vaccinated?” she asked Lee with genuine curiosity. “It’s kind of frightening,” he told her.

Wherever he went, Lee knew that two out of three Mobilians had so far opted out. He just doesn’t know which ones, or what more he can do to avoid the invisible danger they pose. I asked her what it’s like for her among the unvaccinated majority. “Well,” she said. “It’s less pressure on me.”

Vaccination is an act of violence.

The motion is one of force, of penetration, of piercing skin, of muscle-deep stabbing. The earliest immunizations were particularly gruesome and involved scraping cowpox or smallpox blisters and lacing the lucky recipient with a pus-covered thread. Despite about one in four modern adults fearing needles, we opt to call a vaccine the shot or the jab.

But it’s a leap of faith that first sets the needle in motion.

On its own, Covid-19 vaccination is a shield against individuals’ risk of being hospitalized or dying should they make contact with the virus. But millions of individual doses can coalesce into a congregation of immunity that could push SARS-CoV-2 to the margins. “We are protected not so much by our own skin, but by what is beyond it,” writes the essayist Eula Biss. Immunity, she adds, “is a common trust as much as it is a private account.” Vaccination’s most powerful protection is amassed, not allocated. It is an ideal. And it is achieved only when enough individuals decide it’s worth contributing to. “We give up a little freedom to all be safer,” Craig Klugman, a professor of bioethics at DePaul University, told me. The very roots of the word “immunity” reflect this hopeful collectivism: In Latin, munis means a burden, duty, or obligation.

With the help of mass vaccination, humanity has successfully overcome diseases that used to ravage us, including whooping cough, yellow fever, and measles. Vaccines helped us win the Revolutionary War when George Washington decided to mandate smallpox vaccines among troop members who did not yet have natural immunity. Polio—which paralyzed between 13,000 and 20,000 annually—was not defeated until children, dressed in their Sunday best, waited in line to receive a sugar cube blooming with a pink dose of vaccine. After a bad batch of the first polio vaccine—administered by injection years earlier—caused 40,000 polio cases, paralyzing 200 children, and killing 10 more, parents still wanted their children to get vaccinated. “They did it because they saw the greater good,” Maycock said.

Long before she was assistant state health officer with the Alabama Department of Public Health, Dr. Karen Landers was a child who received the polio vaccine and later got a smallpox shot. “We need to do these things,” she told me, so that we can control or eliminate communicable diseases “to the point that many people no longer have to think about them.” This is the paradox familiar to Dr. Bert Eichold II, who has served as Mobile County’s health officer since 1990. A successful public health campaign during a pandemic will eventually render itself invisible. “If we do it really well, the end result is zero,” Eichold said, which critics use to their advantage. “They will say, ‘Y’all did too much. Nobody got sick, nobody died.... That was a waste of time.’”

For mass vaccination to become as protective as possible, enough individuals have to believe in a best-case scenario that looks like nothing at all. In other words: It hangs on blind faith.

The morning she got her Covid-19 vaccine, Abby Wilson, a nurse manager at Springhill Medical Center in Mobile, wrote out notes to her two daughters, a four-year-old and a one-year-old. Wilson often writes them letters to read in the future, when they leave for college, or travel abroad alone for the first time. “Sometimes in life you have to be courageous,” Wilson wrote to her daughters. It was wintertime. Covid-19 hospitalizations were surging. The vaccine had just been approved for emergency use. “I had to decide to have peace about it,” Wilson told me.

Wilson had been praying for an end to the pandemic and asking God for help until then. The call was answered, Wilson said, with vaccines that could blunt Covid-19’s lethal edge. The virus wouldn’t go away on its own. Without protection, the human body acts not only as an unwitting and unwilling viral host, but as a safe harbor for SARS-CoV-2 to multiply and mutate. After almost a year of unimaginable loss, here was a miracle that could shore up individual defenses to Covid-19 and tamp down the dangers we all pose to one another. “This was the beginning to the end,” Wilson said. “It felt like a page was turning,” said her colleague, fellow Springhill nurse Brelee Grow.

By mid-March of this year—about two months after Covid-19 first peaked in Mobile and across the United States—the number of hospitalized patients in the county had dropped by 85 percent, down to just 41 patients. In spring, someone clicked off the massive air filters that had been running nonstop since March 2020 at the nurses’ stations at Springhill Medical. The sudden, fan-free silence invited the thought of what other relief might soon accompany it. “A lot of us thought in the back of our mind that everybody would want the vaccine and get it,” said Paul Tomlinson, registered nurse and Springhill’s emergency and critical care services director.

“It makes me so, so mad,” Tiffany Anderson told me. “None of this makes sense.”

Anderson has had Covid-19 twice. She got vaccinated long enough ago to potentially qualify for a booster soon. She has left the service industry job where, she recalls, customers told her to take her mask off so they could see her smile. When we spoke, one of her best friends was in the ICU, on a ventilator, fighting for his life. Anderson was begging people close to her (including nurses and other medical workers) to get the shot while they could. “I’ll bully you,” she told me. “I don’t care. I want everybody I love to be protected against this.”

Everything that seemed obvious to her (the vaccine’s safety and effectiveness, the dangerous contagion spreading like wildfire through Mobile, the social contract we all share as immunological neighbors) was not evidence enough for her unvaccinated peers. “It’s crazy. I don’t know how you can’t see it,” she said. “It’s a slap in the face.”

Being vaccinated in Mobile could feel like damnation, many told me. They were deeply moved by a social responsibility no one else seemed to feel. They were initially buoyed by the opportunity to make a meaningful individual contribution in the face of monstrous danger. They were condemned to powerlessness as they realized nothing—not data, not personal pleas, not gentle encouragement, not scare tactics—may be enough to achieve herd immunity. “I feel like I’ve done my part to help others out,” Stan, a 37-year-old who works in the hospitality industry, told me. “I feel like they’re not even trying.”

The time for compassion and patience came and went for Gerri Wright once children ended up in the hospital with Covid-19 and some hospitals became overrun with unvaccinated patients. “Now I’m more pissed off about it, to be honest,” said Wright, 31. “If I hear that somebody is not vaccinated, I think, ‘You just went to the bottom of my list of people I want to hang out with.’”

By summer’s end, a righteous anger had mushroomed across Alabama, the South, and the nation. “It’s time to start blaming the unvaccinated folks, not the regular folks,” Republican Governor Kay Ivey told news reporters in Birmingham late this summer. “A lot of us are pissed,” said Susan Hassig, an epidemiologist at Tulane University. “We need national therapy.” Art Caplan, a bioethicist at New York University, told me he thought vaccine refusal should be punishable by law, in the same way a person who purposely hides their HIV status from sexual partners can be held legally accountable for knowingly spreading a deadly disease. “You ought to be sued. You should be personally liable,” Caplan said. Most maddening of all, Hassig said, is that within this gulf lies common ground. “We all actually want the same thing,” she said. “We want this pandemic to be over.”

The rage is palpable, and corrosive. “Everybody is looking at everybody with a little suspiciousness. It’s a great time of distrust,” said Richard Carpiano, a medical sociologist at the University of California, Riverside, who studies vaccine hesitancy. “The well has been so poisoned.” It leaves room for dark, unanswerable questions about what society wouldn’t sacrifice at the altar of a twisted conception of individual liberty. “It craters everything you thought about a community,” Stan told me. “I think there’s a possibility that everything we think about how society functions in this state will come to a screeching halt.”

Many have reached their limit. “At this point, I’m past the point of having a real conversation with them about it. There’s just no point,” Wright told me. “I just have to go back to thinking about myself again.” Some cling only to a hardened faith that the upcoming wave of deaths among the unvaccinated might be the only way to convince them to save their own lives. “I don’t understand why they can’t do it. It’s their problem if they want to get sick,” a veteran in his sixties told me on the day he ventured out to get his booster shot. “Once they see somebody pass away, I guess they’ll realize it’s time.”

Unfortunately, barring that gruesome persuasion tactic, a Covid-19 vaccine about-face at this point in the pandemic will require patience, genuine concern, and a willingness to listen (in short, everything they’re not getting from their unvaccinated counterparts), said Glen Nowak, co-director of the Center for Health and Risk Communication at the University of Georgia. “If you get too adamant, too strident, too strong, people react to how you’re communicating,” Nowak said, and not what you’re saying. “Harsh rhetoric is hardly an effective communication strategy.”

But that is a huge ask, said University of Florida epidemiologist Cindy Prins. “You’re asking me to extend a lot of care to someone who is not doing the same for me,” she said. It’s like doing all the work for a group project, failing, and then being asked to do extra credit to make up for it. Mary, a vaccinated schoolteacher in Mobile County, has reached a painful stalemate amid the chaos. “I don’t know how much yelling or getting mad will do anything. I’m not going to shove it down someone’s throat. That’s not going to convince anyone,” she said. “It has to come from within them, or they’ll have to come face-to-face with this.” These days, she said, the frustration she feels is fleeting. The despair that replaces it feels more permanent. “It makes me more sad than mad,” she told me.

In Mobile County, public health officials have accepted that unfortunate lot. “Right now, we don’t have time to sit around and be frustrated that it didn’t have to be this way. We have to keep working,” said Dr. Laura Cepeda, who left her role as the health department’s chief medical officer a few weeks later. “We just gotta keep digging in and fighting.” The health department’s shift in strategy reflects this reality. Instead of herding as many people as possible to mass vaccination sites, it has spent recent months setting up about 130 pop-up clinics wherever they might reach someone, anyone: parks, barbershops, high schools, coffee shops, art walks, hunting and fishing expositions, churches. “It’s one-on-one, I think, at this point in time,” Dr. Eichold said.

A one-on-one is what reached Lillie McCoy. McCoy, who is in her 40s and suffers from diabetes, heart problems, and high blood pressure, spent almost a week in the ICU with Covid-19 last winter. She was initially skeptical about the vaccine. “I don’t jump on the first thing I see, and I don’t believe everything I hear,” she told me sitting at a table in her restaurant, Soul Heaven Cafe. McCoy is a Black Alabamian, which means she belongs to a demographic that has been grossly underrepresented in the vaccine drive and overrepresented in Covid-19 deaths—a modern shadow of the state’s grotesque history of medically abusing, exploiting, and deceiving its Black residents.

It is a city in Alabama, after all—Tuskegee—whose name alone invokes memories of the entire country’s historic medical apartheid. During the Tuskegee experiment’s 40-year run, researchers withheld syphilis treatment from 600 Black men so doctors could trace the disease’s unobstructed advance from painless sores to bone decay, heart damage, blindness, paralysis, insanity, and death. It was in Montgomery, Alabama, that two Black girls—12-year-old Minnie Lee and her 14-year-old sister, Mary Alice—were involuntarily sterilized at a family planning clinic in 1973; the resulting class-action lawsuit exposed the widespread practice of using federal funds to coercively sterilize poor, Black women. It was in Alabama, during the nineteenth century, that J. Marion Sims, sometimes celebrated as the “father of modern gynecology,” first practiced his surgical techniques on enslaved women, without anesthesia.

When Laffiette gives a sermon like the one he’s named “Covid-19 Vaccine and Being a Black Christian,” he’s speaking to descendants of that legacy. “My people have pause,” he told me. “Those things are still resonating in the minds of people.” In February, reports showed Black Alabamians were receiving a disproportionately smaller share of shots (only about 11 percent of vaccines had gone to Black people, who make up 27 percent of Alabama’s population and 36 percent of Mobile County’s). That gap was partly attributed to distrust sowed by decades of abuse. In response, many Black spiritual leaders in Mobile have turned their pulpits into tools of public health, in the hope that a belief in God—channeled into a faith in the vaccine—might prove more powerful than this history of harm.

Laffiette has invited virologists to join community Zoom calls and answer questions from his 120-member congregation at Bethlehem Missionary Baptist Church. “I want the people of God to understand it’s not a lack of faith to have been vaccinated, to wear masks, to wash their hands,” Laffiette told me. “When I cross the street, I know he’s going to watch over me, but I still look both ways.” In January, he and three other Black clergymen were vaccinated in an event organized and livestreamed by the Mobile County Health Department.

“I can’t trust TV, but I can trust my pastor,” is a common sentiment, said the Reverend Alexander Zack Johnson, pastor at Midway Missionary Baptist Church, which hosts a free Covid-19 testing clinic. He is the husband of Nina Ford Johnson, the president of the county’s medical society, whose first member was a Confederate surgeon and slave owner who argued that whites and Blacks were different species. In her daily work as a pediatrician, she tries to leverage patient-doctor trust in much the same way that her husband does. “Sometimes that’s all you need to do, is plant the seed,” she said. “Somebody else will water it.”

For McCoy, it was precisely that—a conversation with her trusted doctor—that delivered her to certainty. “We got to get vaccinated. There’s no other way,” she told me. The first convert of McCoy’s vaccine proselytizing, her husband, got his first dose on the same day she got her second. She now felt a personal obligation, she said, to shepherd whomever she could from doubt to conviction. “I’m trying to get to heaven,” McCoy told me.

Founded by the French in 1702, Mobile is not only the state’s oldest city, but predates Alabama’s own statehood by more than a century. On Caroline Avenue, in a historic district, the Duffie Oak—a 48-foot-tall giant with a 126-foot limb spread, according to one 2009 description—has stood an estimated 300 years, for practically all of Mobile’s history. Spanish moss sleepily drapes across the rest of its eight million tree canopy, framing the cathedrals, synagogues, temples, mosques, and churches that grace seemingly every street. Hemmed in by the city’s skyline, Mobile Bay’s majestic expanse frequently hosts a spectacle of roiling clouds that have earned Mobile the title of the country’s rainiest city in years past. I found myself thinking often, as I drove around, how beautiful—serene, even—the city looked.

But of course, this is not a city steeped in peace. Its past recounts the story of racial violence in the United States and in the Deep South—from the slave ships that landed in Mobile well into the nineteenth century, to Ku Klux Klan lynchings that continued into the 1980s, and up to 2016, when 19-year-old Michael Moore, who was Black, was shot by a white police officer during a traffic stop. I couldn’t drive around this serene city without thinking also of those things, and of Covid, raging invisibly across Mobile during my stay.

Cases skyrocketed, from about 140 weekly in early June to 2,167 weekly the following month, when Alabama researchers warned they were finding Delta in almost 71 percent of sequenced Covid-19 samples. At the close of July, almost one in three Covid-19 tests in Mobile County was coming back positive, and hospitalizations were surging.

By mid-August, a bad situation was growing worse by the day. Governor Ivey issued an emergency declaration that allowed out-of-state health care professionals to temporarily practice in Alabama and permitted hospitals to free up bed space for Covid-19 patients. With 1,568 patients outnumbering Alabama’s 1,557 ICU beds, the state now touted a “negative” available ICU bed count. “Unlike last year, when we were hoping for a miracle,” Ivey said, now there was the blessing of three free, highly effective vaccines. And in the meantime, the enemy had grown deadlier.

Delta patients, it seemed, needed ICU-level care from the moment they entered the emergency room, said Tomlinson. Staff worried about the hospital’s oxygen supply, and whether the building’s infrastructure could handle running so many breathing machines at once. As soon as a Covid-19 ward was set up, it would fill, Tomlinson said. In one single 24-hour period, 12 patients died of Covid-19. “I’ve been here 25 years; I’ve never seen numbers like this,” Tomlinson told me. “Was there a warning? Yes. Did I think it would be this bad? No.” For staff that had weathered 15 months of the pandemic’s ups and downs, the surge was unbearably dark. “What more can we take?” said Sandy Rodriguez, a nurse at Springhill. Rodriguez said that when she tries to sleep after her shifts, she dreams of her patients’ faces and of the ICU’s never-ending beeps and alarms. “Sometimes you work all night in your sleep.”

After wrapping up my interviews at Springhill, I cried in the parking lot. I thought of Rodriguez, who couldn’t escape the nightmare. I thought of Anderson, whose friend died in a hospital bed that weekend. I thought of Wilson, and the look in her eyes when she talked about how close some patients were to death before they changed their minds about the vaccine. It was as mysterious as God to me how anyone could go on like this. I found myself driving to a liquor store. As I opened the door to the beer cooler, I overheard a customer as he made his purchase. “99.9 percent survival rate,” he told the cashier. “Don’t believe the hype.”

About an hour and a half into my conversation with Kevin Lee outside Soul Caffeine, the discussion turned to what felt to him like the health system’s imminent collapse. One day earlier, doctors in South Florida staged a brief walkout in protest of unvaccinated patients. Texas health care policymakers were discussing whether to take into account a person’s vaccine status when triaging. Mobile had issued an alert that demand for emergency medical care had outstripped the city’s ambulance supply. Jason Valentine, a Mobile County physician, got national news coverage for announcing he would no longer see patients who were not vaccinated against Covid-19. “At what point will everybody break down?” Lee asked me.

A young woman one table over interrupted us with a shaking voice. “I’m unvaccinated,” she said, “and there is not anything, jail or death, that would make me do it.” (A few minutes later, she repeated this shocking perceived martyrdom a second time: “I would gladly die.”) We sat stunned as she launched into a breathless spectacle of paranoia and pain. She knew people who’ve been injured and maimed by the shot. She knew that the vaccine research used aborted fetal cells. She knew that pharmaceutical companies own and operate both the media and the Food and Drug Administration, neither of which could be trusted to tell the truth or serve the public’s best interests. She knew that her vaccination status didn’t prevent the Covid-19’s spread—and that, actually, the vaccine was driving mutations in the virus. And above all, she knew that she felt the vaccine posed a greater risk to her health than Covid-19. “You can’t say, ‘Set yourself on fire to keep me safe,’” she told us. “Not doing it has nothing to do with not caring.” In her eyes, it is stunningly clear, we are the monsters.

“I’m normally a very sweet person, but I just want to cry listening to your conversation, because it’s very hurtful, the segregation that’s happening,” she said. “I know far more unvaccinated people than I know vaccinated. There are way more people not willing. And I’m sorry if that bums you out.” Lee, who had remained composed during the entire eight-minute exchange, told her sincerely, “I’m sorry you feel so persecuted by this.” Without a word, she shook her head, packed up her belongings and walked off, on the verge of tears.

“Someone’s watching them 24/7,” said Rodriguez, the ICU nurse, of her Covid-19 patients. Whether she was referring to God or hospital staff, I could not tell. I do not think the distinction matters. She recounted for me the scene she dreaded most, the one that clung to her even in sleep once a shift ended.

On their insides, the critically ill Covid-19 patients are obliterated, lungs pulped into mush and other organs cascading into failure. On the outside, they are visibly terrified. They are what Rodriguez calls “air hungry.” Each minute, they grasp at 40 to 60 shallow, crackling breaths—about three times as many as a healthy adult would draw in the same time span. Rodriguez ratchets up her efforts to save them. But with the Delta variant, she said, as treatment escalates, the patients typically decline.

At some point, Rodriguez will lay her hands on their chest. She will lock into their eyes. She will press down meaningfully on their ribs, to shepherd their breath away from panic. “Slow,” she says. “Deep.” She prays with oxygen. “We’re in this together.”

But the air runs out for the patients, who suck at it with desperate gasps. Rodriguez extends a blessing under her palms. With patience and faith—and someone to bear witness and ward off life’s longest solitude—another breath may come. It is the purest testimonial I heard during my time in Mobile, but it is one Rodriguez has lived many times over. At the end of each one, Rodriguez stands alone and weary. “I wish people could see that,” she told me, our eyes wet. “I think it would change their mind.”