Heidi Laurson didn’t know how she was going to make it to the end of the summer.

Laurson, a single mother with three grown children and one still living at home, had lost her job during the pandemic. She’d taken a new job as a director of sales and marketing for two hotels in Denver, Colorado, at a paycut. Now she found herself struggling to find summer programs and camps with the necessary resources to accommodate her eight-year-old son, Jack, who has special needs.

“People don’t understand how much additional worry falls on your shoulders, when you’re responsible for everything,” Laurson said about being a single mom. “If you mess up, if you get behind, it could devastate your entire family.”

She had set aside money in anticipation of the financial strain of summer expenses, but the first three weeks of summer daycare for Jack had cost an entire paycheck. There were still two weeks open in August—two weeks when she needed to find care for her son, two weeks that would cost yet more.

“He jumped around to five or six different camps, and it was hard for me. I was kind of piecemealing where I could get him in,” Laurson told me.

A solution appeared in the middle of July, when Laurson received her first monthly installment of the child tax credit that had been updated and expanded by the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan in March. Households earning under a certain threshold started receiving the checks in their bank accounts on July 15: $300 for children under age 6, and $250 for children between 6 and 17, like Jack.

“The July tax credit and the August tax credit essentially paid for those additional two weeks of childcare that I needed to get covered in August,” Laurson said.

She enrolled Jack in a rock-climbing camp, using the $500 from the two payments to cover the two weeks. Unlike other extracurricular activities that he had tried and found overstimulating, like karate, Jack immediately took to climbing. Laurson said she had “never seen him love anything like this before.”

“This is the first extracurricular activity that he’s done that just seems to fill him up with joy,” Laurson said. She intends to use the monthly payments to pay for him to attend a climbing club after school twice a week. “When you live on a tight budget, it’s a luxury to be able to put your kids into extracurricular activities.”

That relief may be temporary. Unless the expanded credit is renewed by Congress, it will expire at the end of the year and revert to its previous form. Laurson and other families now relying on the monthly installments will receive it as an annual lump sum instead. The credit will also shrink back to $2,000, and the cutoff age will again be 16 instead of 17. Laurson says she’s already worried about January, when she will have to start paying student loans that she took out to pay for college for one of her daughters.

“I think it would be wonderful if it is extended,” Laurson said. “It is helpful, having it come to me on a monthly basis like this, something that I can use and budget and have for my child.”

Laurson may not need to be pessimistic: Democrats sit atop reams of new data that show the expanded credit is working for families with children, as well as polling that suggests voters may well reward Biden and congressional Democrats for implementing it. But using these successes as the centerpiece of a midterm election campaign will become much less viable if these benefits are not extended beyond the end of 2021. And despite the Democratic Party’s congressional majorities, the terms of the extension are very much in doubt.

The expanded child tax credit, or CTC, is a cornerstone in President Biden’s “Build Back Better” agenda—an immediate method for reducing child poverty that has produced tangible results, and a bankable applause line in any campaign event.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimated that the changes implemented by the American Rescue Plan would lift more than four million children above the poverty line, cutting the number of children in poverty by nearly 40 percent. The benefit reaches nearly 60 million children in around 39 million households.

“There’s two things I really like about this child tax credit,” Senator Sherrod Brown told The New Republic. “One, it’s predictable, it’s coming every month. And second, we trust families to make the decision [of] how they’re going to spend the money.” The Ohio Democrat has long been a champion of expanding the child tax credit and repeatedly introduced the legislation on which the American Rescue Plan’s expansion was based.

Single filers earning under $75,000, heads of household earning under $112,500, and two-earner households earning under $150,000 receive the full benefit—$3,600 per year for children under age 6 and $3,000 per year for children ages 6 through 17, an increase of $1,000 or more from the previous credit. The credit phases out for higher-income Americans, such that two-earner households earning more than $150,000 and up to $400,000 will receive smaller payments, totaling $2,000 per child. Families can opt out of the prepayments through the IRS website, which may be preferable for higher-income households that don’t need monthly payments and want to claim the full credit when they file their 2021 taxes.

But the regular payments are critical for parents like Laurson, who can use the checks to make decisions about what their children need on a month-by-month basis, accounting for life’s unexpected twists and turns, instead of making a decision when they receive a lump sum at tax-filing time.

Because the credit is also fully refundable, it is available for the first time to children with parents whose incomes are so low that they don’t need to file taxes. These families were previously excluded from receiving the credit, leaving poorest children behind. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, or CBPP, around 27 million children under 17—including roughly half of all Black and Latino children and a similar number of rural children—received only partial credit or none at all because they lived in families with incomes too low to qualify for the full credit.

The Biden administration, the Treasury Department, and Code for America recently collaborated on a new nonfiler online tool that launched on September 1, replacing the previous portal that the IRS initially implemented, which drew widespread criticism from lawmakers, nonprofit groups, and legal aid organizations about its poor mobile accessibility, complicated language, and lack of Spanish-language translations.

It is, in short, still a work in progress—but the early data shows that the expanded CTC is accomplishing the Biden administration’s goal of cutting down on child poverty and generally making life easier for low-income families. It’s also providing some significant economic stimulus: An August report by the Niskanen Center, issued after the first checks were distributed, estimated that the expanded CTC would “boost consumer spending by $27 billion, generate $1.9 billion in revenues from state and local sales taxes, and support over 500,000 full time jobs at the median wage.”

The number of adults with children reporting that their household didn’t have enough to eat dropped by 3.3 million between early July and mid-August, after the first two CTC monthly payments were distributed, according to a report by the CBPP based on data from the Household Pulse Survey conducted by the Census Bureau.

“The CTC is certainly not a panacea. We’re not living in a perfect utopian world just because we rolled out the [expanded credit],” said Lindsay Owens, an economist and the executive director of the Groundwork Collaborative, an organization that advocates for progressive economic policies. “But cash benefits are really powerful.”

Carmen Rodriguez, a grandmother of nine living in Connecticut, said in an event with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Connecticut-based lawmakers and officials, that the credit was “gratefully needed.” Rodriguez, who recently lost her son and is now raising his children along with her other grandchildren, credited the CTC for providing the means by which her kids could get caught back up after the pandemic had left them “a year behind or more” educationally. “Without a father, now this money is stepping up and helping with the kids’ education and keeping them focused and on the right track so that they won’t fall through the cracks,” Rodriguez said.

A poll conducted by Parents Together Action, a nonprofit advocacy group, after the first payment, found that 50 percent of parents surveyed said the checks made a “huge difference in their lives,” and 40 percent said it was “helpful but not a huge difference.” Moreover, 85 percent said that it was extremely or somewhat important for the monthly checks to continue after December, and 58 percent said that they would be “much more likely” to vote for politicians who support a permanent extension of the credit.

Brown said that the expanded child tax credit could ultimately have an impact on the economic landscape similar to that of the creation of Social Security and Medicare.

“There’s no question that Congress’s commitment to seniors—Social Security and Medicare—was transformational in the lives of American people. We’ve not done the same commitment for children until now,” Brown said. “And this will be transformational in the way that Social Security and Medicare [were].”

Some members of Congress have advocated for an expanded child tax credit for years but have faced opposition from lawmakers of both parties concerned about the optics of implementing a program that could be construed as welfare. Resistance slowly thawed among Democrats. When Brown first introduced a bill expanding the child tax credit in 2013, it had 36 co-sponsors; when he reintroduced the bill in 2019, this time including monthly distribution of the credit, it had support of all but one member of the Democratic caucus.

The coronavirus pandemic scrambled calculations about what the federal government owes its citizens in times of crisis. Republicans and Democrats suddenly supported direct cash payments to struggling Americans, and much-appreciated stimulus checks flowed forth. A provision expanding the child tax credit was tucked into the American Rescue Plan, which became law last March.

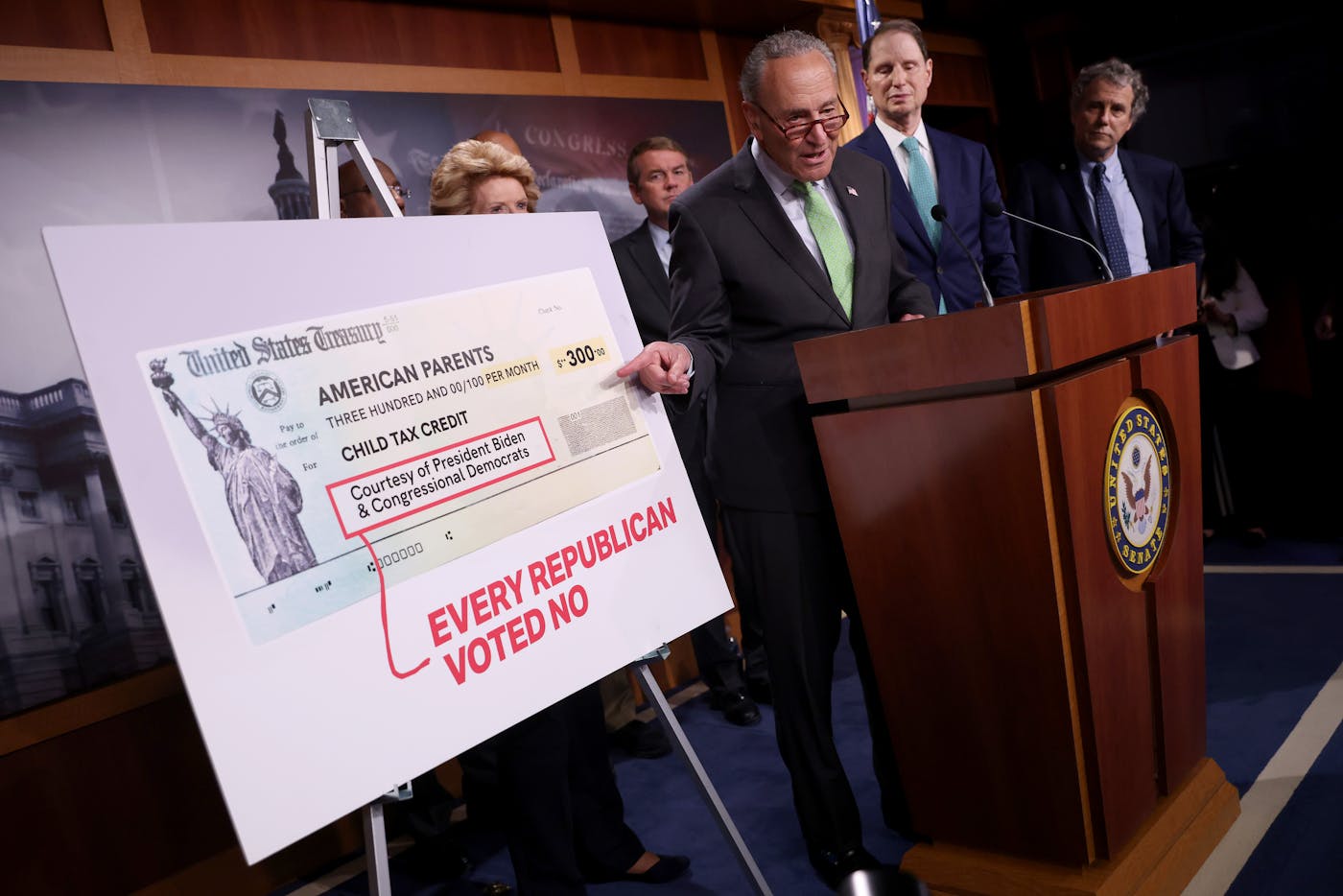

Democrats have been eager to promote the expansion of the child tax credit since it took effect in July. Ahead of a midterm election where Republicans are structurally advantaged, the CTC expansion is a slam-dunk policy win that vulnerable Democrats can use in their campaigns. Campaign arms are already getting in on the action: The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee issued a press release in late August citing a report from Columbia University’s Center on Poverty and Social Policy, which found that the monthly child poverty rate fell from 15.8 percent in June to 11.9 percent in July 2021. The release noted that “every single Republican incumbent and Senate candidate opposed this critical tax relief for hardworking American families.”

Congressional Democrats have included a CTC extension in their massive, multitrillion-dollar budget bill. That measure, which includes a laundry list of progressive priorities, must pass through what’s known as “reconciliation,” a legislative process that allows certain bills, which meet conditions laid out by the Senate parliamentarian, to sidestep the 60-vote supermajority requirement imposed by the filibuster—and Senate Republicans. The American Rescue Plan was also passed through reconciliation.

But as Democrats continue to wrangle over what’s to be included in the budget bill, it remains unclear whether a permanent extension of the CTC will survive, despite its efficacy and popularity. Although congressional Democratic leadership initially proposed a price tag of $3.5 trillion for the reconciliation bill, several moderates have balked at the cost. With thin margins in both houses of Congress, the bill cannot afford to lose many votes.

In addition to the CTC, Democrats will have to figure out how and whether to include other elements of their agenda, such as expanding Medicare to include hearing, dental, and vision benefits, expanding Medicaid coverage under the Affordable Care Act, establishing universal pre-K, and implementing paid family and medical leave. Many of these priorities may end up competing for space in the final bill.

“Where would you cut? Childcare? Family medical leave, paid for? Universal pre-K? Home health care?” Speaker Nancy Pelosi said in a press conference last Wednesday, challenging Democrats who have balked at a larger bill. “We will have a great bill, and I hope that as people are looking at numbers, they’re weighing the values and what we can accomplish with that legislation.”

To paraphrase an old truism, there’s no such thing as a free expanded child tax credit. The Joint Committee on Taxation puts the cost for the temporary one-year expansion of the credit at $110 billion, and it could cost $450 billion if extended through 2025. The Tax Foundation, a conservative think tank focused on tax policy, estimates that the expanded credit would cost $1.6 trillion over 10 years if made permanent. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, a nonpartisan budget watchdog, estimates a cost over 10 years of $1.1 trillion. (Some of those expenses may be recouped—a study by Columbia’s Center on Poverty and Social Policy released in August found that the “value of current and future benefits for society equals roughly $794 billion, or approximately eight times initial costs.”)

Given the cost considerations, congressional Democrats may opt for a temporary extension of the expanded CTC for two or three years, rather than a permanent one. It’s also possible that there could be a compromise in the final bill that reduces the amount of the benefit while retaining its pandemic-era innovations, such as the monthly distribution and expanded access to poorer households that don’t file taxes.

In a press call with reporters last Wednesday, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer stayed vague on what the child tax credit provision will look like in the final reconciliation bill. Although he called it “one of the most important things we’re doing” and promised to “certainly extend it for a good period of years,” he did not specify how long that extension would be.

“We’re going to make it as strong as we can,” Schumer vowed. In the same call, Senate Budget Committee Chair Bernie Sanders promised to “extend it to as far as we possibly can within the $3.5 trillion,” without offering any details.

The House Ways and Means Committee released a proposal on Friday extending the child tax credit through the end of 2025, and keeping it at current levels. But as the proposal has not yet been conferenced with the Senate, it’s unclear whether this will be the final version of the extended tax credit.

Brown believes there is “almost zero chance” that the reconciliation bill would lower the amount of the credit. He said that he was “confident the child tax credit will exist in very close to its present form for the rest of my life.” Brown said, “Every Democrat buys into this. I think every Democrat wants to see permanence. I know every Democrat likes the expansion, the larger amount, and likes the predictability, and likes the monthly payment, and likes the full refundability.”

As with most of the details of the bill, it’s unclear what the final list of revenue streams will look like, because it will have to appease all the various factions of the Democratic Party. Part of the reason why Republicans are not expected to support the reconciliation bill—beyond the price tag—is that the offsets are expected to increase taxes. Biden has pledged no American earning under $400,000 would see their taxes increase, but the White House considers the wealthy and corporations to be fair game.

Democrats are considering a host of proposals to fund the massive bill, including overhauling international taxation standards, raising the corporate tax rate, and raising income tax rates for Americans in the highest tax brackets. Another possible revenue stream, taxing appreciated assets upon death, has faced criticism from some Democrats who say that it will hurt farmers and small-business owners. Predictably, corporations and business groups have begun lobbying against the reconciliation bill.

With a disappointing August jobs report and high deficits, Republicans want to put the brakes on spending—an argument not inimical to moderate Democratic Senator Joe Manchin, who called for a “strategic pause” on the reconciliation bill, saying in a Wall Street Journal op-ed that he “can’t explain why my Democratic colleagues are rushing to spend $3.5 trillion.” (Schumer rejected the “strategic pause” idea last week, saying Democrats are moving “full speed ahead.”)

Manchin on Sunday reiterated that he would not support a $3.5 trillion price tag for a final budget reconciliation bill. He also raised concerns about the child tax credit that echo some conservative critiques—namely, that the expanded credit is not tied to work requirements.

“I support child tax credits. I sure am trying to help the children,” Manchin said on CNN on Sunday. “There’s no work requirements whatsoever. There’s no education requirements whatsoever for better skill sets. Don’t you think, if we’re going to help the children, that the people should make some effort?” (Food insufficiency among adults with children in West Virginia dropped by three percentage points after the first monthly installment, according to the West Virginia Center on Budget and Policy.)

Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders offered a riposte to his West Virginia colleague: “I would not want to be a Republican in that position to tell working families, working parents, who have been able to put aside a few bucks to take care of their kids that we’re gonna end that program at the end of the December. So we’re gonna do our best to extend it for as long as we can.”

But Manchin doubled down on Tuesday, insisting that “tax credits are based around people that have tax liabilities.”

“I’m even willing to go as long as they have a W-2 and showing they’re working,” he said.

Others are concerned about whether the permanent expansion of the CTC is the most cost-effective way to aid low-income children. “It’s definitely a policy that I would be more sympathetic to as a short-term proposal than as a permanent one,” said Scott Winship, the director of poverty studies at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank, who has written a report proposing changes to the earned-income tax credit and the child tax credit.

Winship is also concerned that providing the credit to low-income families without tying it to job requirements might disincentivize unemployed parents to find work. But a recent report studying the impact of Canada’s child tax benefits found “no evidence” that the policies “had a significant impact on the labor supply of single or married women with treated children.” A 2019 report by the National Academy of Sciences found that the vast majority of people in low-income families would continue to work after an allowance of $3,000 per child was implemented and that most would not reduce their work hours.

Chye-Ching Huang, the executive director of the Tax Law Center at New York University, said that many of those who might reduce their work hours or leave the workforce may have young children and would be taking leave for caregiving purposes. Huang noted that, while the research into how direct investments affect intergenerational poverty was relatively new, “the impact of lifting children out of poverty ha[s] these really long-reaching benefits.”

“A lot of the time, to the extent that such families are not at work, it’s for a temporary period,” Huang said.

The Biden administration has emphasized its support for the “middle class,” a nebulous phrase with multiple meanings that people in higher tax brackets often ascribe to themselves. In a memo to House Democrats on political messaging on Biden’s agenda, the White House urged lawmakers to highlight the extension of the child tax credit to constituents, among other “Build Back Better” policy priorities—focusing particularly on how the agenda will affect middle-income families.

Isabel Sawhill, a senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institute, has argued that tax credits need to be more targeted to lower-income households and that some of the funds spent on expanding the tax credit could instead be used to invest in education, health care, and nutrition.

“I’m not saying that low-income parents don’t need more money. I’m just saying middle-class families probably don’t need money—their children probably don’t need money as much as they need a better education and better health care,” Sawhill said.

But education and health care investments are also on the to-do list for Democrats, who have recently made a practice of rhetorically broadening the definition of “infrastructure” to encompass social systems as well as physical ones. To further underscore this, Democrats have tied their ambitious budget plan to a bipartisan infrastructure bill in a marriage of agenda items.

If the reconciliation bill manages to wed the child tax credit expansion to other social policies, including providing universal pre-K and paid leave, that could help lift children out of poverty in a more sustainable way. Therein lies one of the main purposes of the reconciliation bill, if it manages to pass with its primary priorities intact: It invests in the complex infrastructure of childcare in a way that reverberates throughout the economy for decades to come.

Brown says the arrangement builds a “foundation for families,” with the expanded child tax credit as a cornerstone in that edifice. With the credit, parents are “going to buy better food for their kids, they’re going to be able to make their home safer, they’re going to be able to give their kids more opportunity,” he said.

If just a few changes to the tax credit can lower child poverty, can decrease food security, can aid the education of Rodriguez’s grandchildren, can help Laurson’s son go to rock-climbing camp—if just a few changes can make a big difference, Brown and the credit’s supporters argue, how can Congress choose not to extend it?

“Everything I do is going to be aimed at making sure this doesn’t go away,” Brown said. “I don’t speak in superlatives often, but this is the most important thing I’ve ever done.”