The hard part of Democrats’ massive

$3.5 trillion reconciliation package kicked off Thursday with multiple

congressional committees beginning their markups of the proposal. Democrats are

sure they’re going to pass something, although exactly what is way up in the

air. So the core questions at hand are not if the reconciliation package will

move forward but how big it will be and what taxes will be included.

There are ongoing fissures between various factions within the party on the spending part of the package. Those are well known. But more ominously, and less publicized, are the differences on the revenue side. This is probably the most perilous part of passing any major piece of domestic legislation.

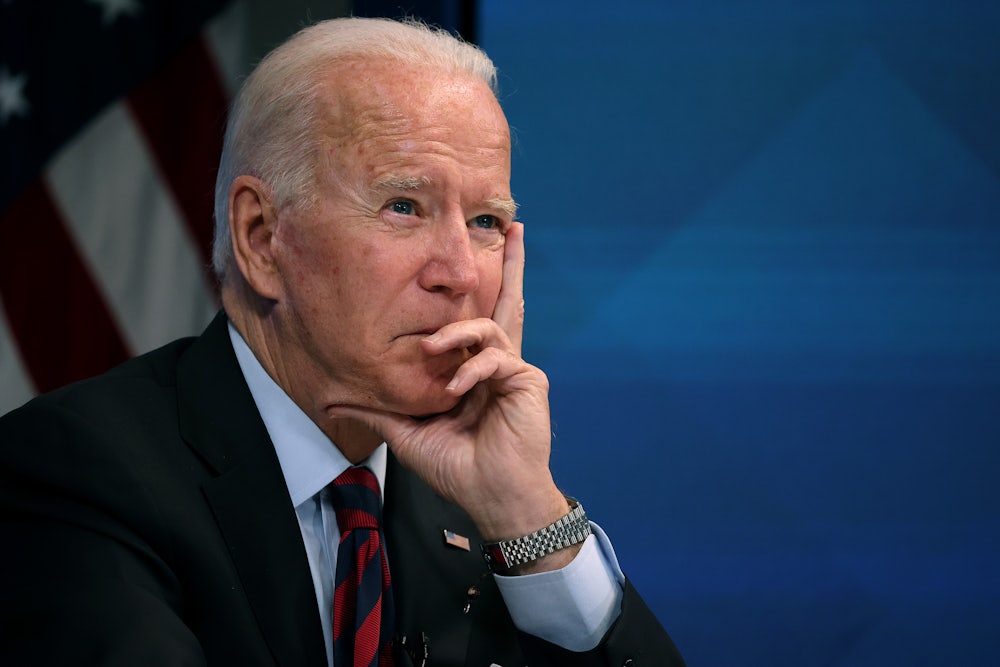

President Biden has often argued

that the country needs to make an about-face on economic policy to benefit the

middle class and the poor. He’s argued for more public investment but also

effectively called for rethinking the decades-old idea that tax cuts are

universally beneficial. The taxation part of Biden’s $3.5 trillion

reconciliation package is essentially the biggest test yet for his

administration and Democrats in general. Can they finally pass something that breaks

from 40 years of tax-cut orthodoxy? And there are more specific tensions among

Democrats about the revenue side that span from the best-known Democrats in

Washington to the key committee chairs in the House and the Senate to the less

high-profile lawmakers. Waiting in the wings is the anti-tax conservative

opposition that is gearing up for a battle it is all too familiar with

waging.

Figures like Senators Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema, House progressives, the small block of House Democrats concerned with removing state and local tax deductions, Senator Bernie Sanders, and the White House have all voiced sticking points on various aspects of the package. It’s enough to think the proposal is doomed. But Democrats argue that the package needs to pass, and it will pass in some form.

“It’s a three-dimensional chess game involving the left in the House, Manchin and Sinema, Pelosi, Schumer, and Biden,” former Representative Barney Frank said in an interview on Tuesday. “I’m pretty confident that they’ll wind up with something. It won’t be $3.5 trillion.”

Frank noted Manchin’s opposition to the $3.5 trillion price tag, a position that Sinema is somewhat in line with. Meanwhile, Sanders, who wanted a reconciliation package in the $6 trillion range, says $3.5 trillion is already a major concession. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer has brushed aside Manchin’s call for a pause, saying his caucus is “moving full speed ahead” with the $3.5 trillion plan rather than paring it down. Other top Democratic lawmakers suggest that the end result could be somewhere between Manchin’s $1 trillion and the $3.5 trillion. But that leaves a whole lot of wiggle room.

Democrats are also quick to note the underlying differences between Senate Finance Committee Chairman Ron Wyden and House Ways and Means committee Chairman Richard Neal. “Neal’s a little more conservative about business,” Frank said. “[But] when you’re talking about Neal and Wyden, you are clearly talking about two people who are very committed to getting this done for a range of reasons—ideological, political, their own personal accomplishment. So yeah, I think that’s an issue that will be talked about, but I think it will get worked out again.”

The differences between Neal and

Wyden are essential and could decide the course of Biden’s overall package, as

well. Wyden is more aligned with the liberal wing of the party. Neal is

regarded as a bit more business-friendly. Wyden has proposed

a set of taxes on executive compensation, increasing the estate tax, and establishing

a tax on billionaires to pay for the reconciliation package. Neal and his

committee have been working on their own set of tax increases, and they have

largely kept quiet on them so far. Major differences between the two committee

chairs on revenue sources could extend the tax-writing aspect of the

reconciliation bill longer than it otherwise might be—and fuel anxieties among

shakier Democrats that an extended debate over taxes could roil the party

heading into 2022.

Arguably, a bigger intraparty flashpoint is on state and local taxation, or SALT. The blueprint for the reconciliation bill directs lawmakers to include a limit on how much taxpayers can deduct from federal taxes. A group of 30-some lawmakers from states with high tax rates have vowed to oppose the reconciliation package unless the cap on deductions is gutted from the bill. On the other side, liberals see gutting the limit as an effective tax cut for just the superwealthy.

In an interview earlier this week, Democratic Representative Tom Suozzi of New York, who has been leading the “SALT Caucus” told Bloomberg News, “I will support my progressive friends and the Democratic caucus on big, bold initiatives, on getting things done to improve people’s quality of life,” before adding, “no SALT, no deal.”

If these Democrats are serious, their opposition could upend the entire reconciliation package. It’s not clear whether these Democrats really want to be responsible for tanking one of the key policy pillars of Biden’s legislative agenda over a tax-deduction cap. Democratic leadership and the White House haven’t moved with the urgency one would see if the threat were considered serious.

The White House has been circulating a memo on Capitol Hill, obtained by The New Republic, promising that the reconciliation bill will cut taxes for the middle class while effectively raising taxes on the wealthiest Americans to set a fairer landscape. The White House plans to make a national push in support of the bill.

“To do that, we aim to tell a clear story about what the Build Back Better agenda will do to level the playing the field for working people, make corporations and the wealthiest pay their fair share and lower costs that are critical for working families, like prescription drugs, home care, and child care; as well as the growing costs of climate change,” the memo, authored by White House communications director Kate Bedingfield, reads.

And last week a leaked chart of possible revenue provisions for the reconciliation bill surfaced out of the Senate Finance Committee. The chart included increasing the corporate tax rate from 21 to 25 percent, allowing the top marginal income tax bracket rate to rise less than three percentage points by 2025, estate tax reforms that would cut loopholes for the estate tax, and updating Treasury Department regulations to prevent “non-economic valuation discounts.”

Meanwhile, there’s a robust lobbying

and anti-tax effort underway, led by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Elsewhere, former

Democratic Senator Heidi Heitkamp is at the vanguard of an effort to kill the tax

increases on corporations and large inheritances in the reconciliation package.

Heitkamp has been making appearances on CNBC to make

the case, a continuation in her shift from the last of the moderate Great

Plains senators to former lawmaker to anti-tax Washington insider.

She’s not alone among former Democratic legislators. “I’ve seen that some Democrats are looking to increase taxes on corporations and wealthy individuals to pay for their spending, which shouldn’t come as any surprise,” former Representative Nick Rahall, a Democrat from West Virginia turned lobbyist, wrote in the Charleston Gazette-Mail. “However, some of these provisions will actually make it harder for our family-owned businesses and farms to stay open.”

And this is the kind of fight that attracts the most famous anti-tax maven in American politics: Grover Norquist. Norquist said his Americans for Tax Reform group is planning on “highlighting the damage done by each of these taxes, talking to voters in districts where the congressman or woman could decide to vote either against the whole package or more likely be part of scaling it back.”

But Norquist predicted that in the end something will pass. “Well, the D’s will pass something, they’ll pass some tax bill, some spending bill,” Norquist said. “The question is what’s the spending number? And Manchin gets to be part of that negotiation, so not $3.5.”

During the Ways & Means markup on Thursday, Republican committee members were sounding the all too familiar anti-tax tune and fomenting the red-blue divide. GOP Representative Drew Ferguson of Georgia warned that the reconciliation bill would only help “liberal wealthy elites build back better,” while rural America, hard-working entrepreneurs, and small businesses would suffer, to the benefit of the country’s global adversaries.

The irony here is that the

reconciliation bill, at its current level, would direct massive amounts of dollars

to rural America. In addition, there’s the reality that raising taxes results

in, well, higher revenues. “The bulk of deficit reduction from all the budget deals of the

last 40 years came on the tax side,” Bruce Bartlett, an economist, historian,

and former Treasury official during George H.W. Bush’s administration, wrote in

an email to me.

Despite all the crowing about the dangers of increasing any taxes at all, the record is pretty clear. The last two presidents who saw deficit reductions were Democrats Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. The last two presidents who left office having passed tax cuts saw deficit increases: Donald Trump and George W. Bush. And, as Bush presided over the Great Recession and Trump the pandemic downturn, it’s also the case that Obama and (especially) Clinton oversaw better economic growth. Clinton’s 1993 budget bill, which raised taxes even on the middle class, was cited often by economists in the 1990s as having helped kick-start the late-1990s boom.

Biden obviously wants to join Clinton and Obama rather than Trump

and Bush on this historical ledger, and indeed he proposes to go further than either.

But he and the Democrats have many hurdles to overcome first.