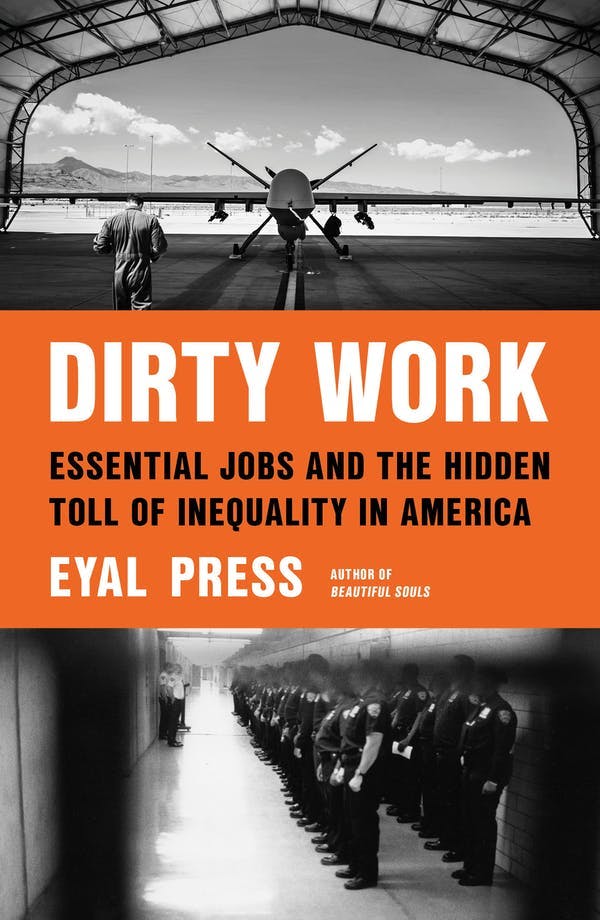

Heather got a job as a drone operator because she wanted to get out of small-town Pennsylvania and she didn’t have money for college. Now when she passes the Beale Airforce Base in California, Eyal Press writes in his new book, Dirty Work: Essential Jobs and the Hidden Toll of Inequality in America, she glares at the anti-war women’s group that throngs the entrance. “They didn’t know what kind of shit we had to see,” Heather said, “they didn’t know most of us wanted to go home and fucking kill ourselves.”

Press can take it for granted that, in 2021, his reader will understand what kind of opprobrium drone operators receive from other people. It’s a form of warfare that veils violence in science and diminishes it by distance; for this reason, drone operators, much like prison custodians, feel little solidarity from workers in more highly esteemed sectors of otherwise similar jobs in the military or police.

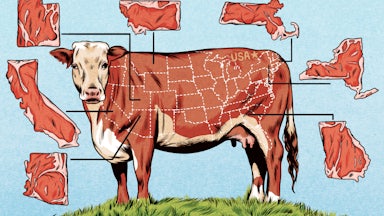

One Beale protester told Press that drone workers “have a responsibility,” since they are “the ones that are doing the killing.” And yet Heather did not create the drone program, any more than the “knocker” at a pork slaughterhouse kills pigs for his own enjoyment. Instead, Press argues, this kind of worker carries a moral burden on behalf of society writ large. Employed to keep the violence of prisons, slaughterhouses, and battlefields out of public life, these workers, Press argues, essentially function as trauma buffers for everybody else.

Press’s cases are diverse and compelling, among them the story of the prison psychiatrist who felt she had no choice but to turn a blind eye to the violence meted out by the guards, and of the oil rig worker in Louisiana who personally has to live amid the pollution his own employer has wrought on that state’s coastline. The term Press coins to describe this kind of labor is dirty work, in the sense that the people who do these jobs are doing everybody else’s dirty work for them.

Dirty workers carry out actions with a “tacit mandate” from a society—which wants the jobs done, considers them necessary, but prefers to have the whole process kept out of its sight. The very notion of civilized and hygienic public life, in fact, relies on all this staying private. But the task of keeping blood off the streets collaborates with the logic of social shame, where secrets mean unpleasantness.

So “dirty work” is Press’s definition of a “kind of unseen labor that is necessary to society” but that takes a toll on workers in the form of guilt and shame. Doing such stigmatized or morally compromised work incurs some very specific psychological effects, he argues, which in America are compounded by the fact that most of these jobs are taken not out of choice but out of economic necessity. The shame that afflicts millions of American workers is, Press argues, an uncompensated and very real occupational hazard.

A key term in Press’s lexicon is “moral injury.” He takes the concept from Jonathan Shay’s 1994 book, Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and the Undoing of Character. In the Iliad, Shay observes, Achilles’s character is undone by the betrayal of his commander, Agamemnon. It violates Achilles’s sense of “what’s right” and makes him “do things that he himself regarded as bad,” Shay writes.

After working with veterans of the war in Vietnam, Press writes, Shay became convinced that “moral injury is an essential part of any combat trauma. Veterans can usually recover from horror, fear, and grief once they return to civilian life, so long as ‘what’s right’ has not also been violated.” So Shay’s theory suggests that it’s not violence itself that causes trauma but that the sense of lacking a good reason for doing that violence “impairs a person’s dignity.” While that might be a delicate notion to articulate, it doesn’t detract from its concrete reality or the suffering that our supply chains expose only certain workers to. Secrecy enhances those feelings of shame; it’s obvious but worth considering that we kill animals behind closed doors, out of the view of respectable society, in a way similar to how Heather eliminated people from a distance.

In Heather’s first week at her job at the Air Force Base, for example, she “watched the screen flash and then saw the thermal signature of blood oozing from a corpse.” This felt fine, until she examined documents about different Afghan dialects and tribes. Gradually, she realized that operating drones is a terrible, terrible job, but she had already witnessed and caused human death by the time she stopped to contemplate what it entailed.

She had suffered moral injury, in a way that is similar, Press argues, to that suffered by a pork slaughterhouse worker. “The worst thing, worse than the physical danger,” one source says, “is the emotional toll. Pigs down on the kill floor have come up and nuzzled me like a puppy. Two minutes later I had to kill them.” A worker in a similar facility for cattle advised an undercover journalist to avoid working as a “knocker,” the person who actually delivers the fatal blow to the cow. “That shit will fuck you up,” he said.

In her convenient social invisibility and in her cleanliness level, the dirty worker resembles, Press points out, the coal miner that George Orwell described in The Road to Wigan Pier. He is “a sort of grimy caryatid upon whose shoulders nearly everything that is not grimy is supported,” Orwell writes, including “you and I and the editor of the Times Lit. Supp., and the Nancy poets and the Archbishop of Canterbury and Comrade X, author of Marxism for Infants.”

Orwell brings in Marxism because the specter of the exploited everyman is often raised solely for purposes of political rhetoric. Orwell here was describing an exploitative labor dynamic specific to fossil fuel mining, but Press borrows his imagery for something more complex: a dynamic of affective inequality, whereby millions of people in America who eat meat expect other people to kill their animals and guard their prisoners and wage their wars for them, at bargain basement prices. In this system, literal dirt in the form of blood or coal helps mark the morally compromised worker as unclean.

As Press’s subtitle suggests, the Covid-19 pandemic has “revealed the degree to which more privileged Americans with the luxury to work from home were dependent on millions of low-wage workers—supermarket cashiers, delivery drivers, warehouse handlers whose jobs were deemed too critical to be halted.” Designating such workers “essential” under a pandemic, as J.C. Pan has argued on this website, has shown just how hollow promises like “hazard pay” are under real emergency conditions.

The new wave of writers reconceptualizing work in the post-Covid world echo many older traditions of political analysis. When I read the title Dirty Work, I thought it was going to be a work of old-school, sociology-flavored feminism—or perhaps a study of the types of work conventionally understood as done by women and therefore badly compensated both materially and symbolically. I expected Press to discuss sexuality as part of his consideration of morality and “dirt,” to discuss a link between sexual dirtiness and the way women disproportionately encounter literal dirt, as carers, sex workers, childbearers, and domestic workers.

Instead, Press’s concept of “dirt” is gender-blind and therefore, in theory, defines “moral injury” as a locus for worker solidarity, because it is experienced by all kinds of people in similar ways, whether in war, at work, or at home. But by avoiding the seemingly obvious way into the subject, through feminism’s articulation of invisible forms of work, like Arlie Russell Hochschild’s ideas about “emotional labor” and “the second shift,” Press occasionally seems to miss opportunities to strengthen his own arguments.

One such opportunity comes when he speaks to Flor about her husband, a supervisor at the chicken factory where she works. “Why do you pressure the workers so much?” Flor would ask her husband, “pleading with him to advocate on their behalf.” He replied, Press writes, that the “pressure she felt was nothing … next to the pressure that he and his fellow supervisors felt from their superiors, who badgered them at meetings to push the workers even harder.” Press here skips over the way “moral injury” is multiplied by the vector of gender. Flor has her own mental and physical scars from working in a chicken factory, but she also has to take on and accommodate the emotional pain felt by the breadwinner of her family, who is also literally her boss.

Dirty Work may actually be stronger for the fact it does not make the broadest possible claims based on the data and stories it contains: Despite its low-key, sociological timbre, Press’s reporting contains an unusually high-feeling number of women sources, with whom Press appears to have fostered long-term trust. Flor tells him about her childhood, for example, and how she fended off her stepfather with a knife; Harriet, the former prison psychiatrist, tells him how it felt when a prisoner whispered to her, “You know they starve us, right?” Press knows how to frame a human story.

It’s in a collective act of witnessing that Press finally finds a resource specifically for traumatized workers like Heather. He describes a meeting he saw take place at a Philadelphia VA hospital, “where people gathered to hear veterans talk about the moral transgressions they had committed in the course of fighting America’s recent wars.” Communal witnessing is a powerful salve to dirty work’s type of shame, the meeting showed him. At this event, the audience members spoke in unison, as if dispensing a doctor’s prescription for treating moral injury, in what Press calls a message “all dirty workers deserve” to hear:

We put you into situations where atrocities were possible. We share responsibility with you: for all that you have seen; for all that you have done; for all that you have failed to do.

By extending the concept of moral injury to the workplaces of millions of workers, Press offers readers a chance to be witnesses too.