The people selling fake vaccination records online are ravenous for my attention. The Telegram channels ping me at all hours of the day with emoji-laden reminders to deal only with verified sellers, copy-and-pasted passages from anti-vax e-books describing infertility, pulmonary issues, and neurological degeneration. “THE ONLY WAY FOR YOU TO BE FREE IS STAYING AWAY FROM THE VACCINE AND GETTING A LEGIT COVID-19 CARD,” warns one seller who says they can ship me a “verified” card for $250, which could be paid in crypto, of course. This person refers to themselves as “Dr. Will.” A lot of the sellers use the honorarium, as if it could possibly translate into a better piece of card stock filled with more convincing script. The proprietors of Instagram accounts that appear and disappear every eight hours or so have the cadence of teenagers, and about the same level of patience. “Hey wb the cards” writes the person behind an account called Vaccination Card Covid when I stop responding to emails, and then, a day later, just: “Hey.”

But why would I spend a couple hundred bucks on a piece of paper filled with the unintelligible handwriting of an imaginary, overextended nurse? Forging a vaccination card is a crime, but if we could move into theoreticals for a moment: It would take me about five minutes to find and download free image-editing software, and about seven more to locate a sample template of a vaccination card posted on a state-run site. It would then be quite easy to alter, print it, and fill it in myself, being careful to use different pens for each imaginary jab (or just the one if I’m feeling lazy and decide to forge the Johnson & Johnson shot instead). And then, again theoretically, I could upload it to New York City’s official vaccine passport app—a program that, despite being developed by a city with some of the strictest vaccine mandates in the country, rolled out a verification system that is nothing more than a simple photo app. I could almost certainly use this theoretical card to get into any establishment in my Brooklyn neighborhood, because the vacuum where a vaccine certification effort might be has been filled with what are functionally index cards and the discretion of exhausted bartenders or museum ushers managing a rush of tourists for around $15 an hour.

As summer rolls toward an uncertain fall and a handful of local governments impose vaccine mandates for entry into restaurants or gyms, it’s vaccine fraud season in the United States. According to a report from the security research firm Check Point, vendors on the dark web hawk vaccine certifications from nearly every imaginable country, the demand for their products spiking in tandem with new restrictions and laws. Fake cards have been spotted on Shopify, on Etsy, and on Amazon for months.

The fervor of that market is somewhat at odds with the administration’s existing position. Faced with so much government distrust and a deeply politicized crisis, President Biden’s various spokespeople remind the public just about every week there will be “no centralized universal federal vaccinations database” and “no federal mandate” to be vaccinated. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention doesn’t keep records about who has been inoculated, and only a handful of cities and states have announced or launched efforts more secure than the vaccine card—the kinds of digital passports that, if not designed carefully, could have the potential to track users or irrevocably change how other credentials are stored.

Nearly two years into the ongoing pandemic, as the delta variant circulates and introduces any number of risks, the charge to return to normal is hinging on the validation of flimsy records by a patchwork of state agencies and employers. As with mask mandates, it’s also relying on the successful transformation of some of the lowest-paid workers into agents of public health. (Recently, I asked a Manhattan bartender how she’d found it to check vaccination cards along with IDs. She told me one guy tried to show her the emailed confirmation of his vaccination appointment and she had absolutely no idea how to react.)

There’s something faintly ridiculous, then, about the vaccine card black market. At its core, it’s a group of people exchanging large sums of money for pieces of cheap card stock in anticipation of an event the administration has built its policy on refusing to invoke, largely out of deference to the idea that extreme paranoia is a private and personal choice a person makes for the sake of their own health.

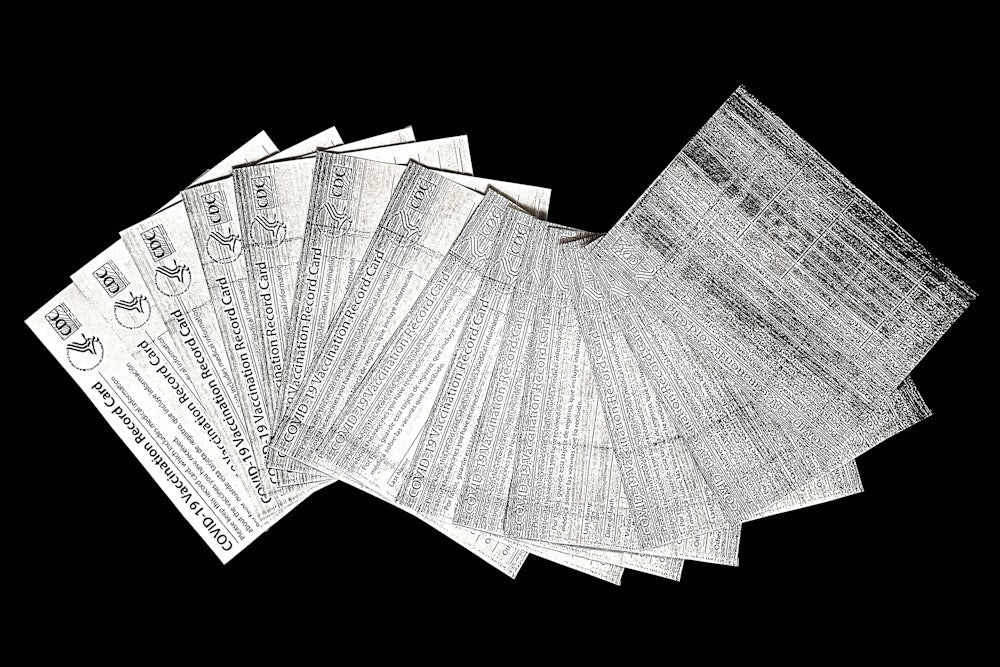

Given everything that precipitated it, the vaccination card is oddly disappointing, the horror of the pandemic answered with a piece of paper that looks like an award an elementary school teacher might give out. In the absence of any clarity from the CDC on how those white cards were designed, public health experts have offered a variety of opinions, the most compelling of which is that in the midst of a once-in-a-lifetime crisis, getting shots into arms took priority over meditating on the particular shape of a government-issue form. (As one person told The Atlantic, it’s probably part of the same structural lag that had state-level officials sending crucial infection data to the feds over fax.) It’s the kind of unexamined but wildly consequential decision that makes sense in the grim chaos of the country’s Covid response, and one that was noted early by people like Ed Felten, a former government officer and longtime security researcher. Was the card a certificate? A reminder to get the second jab? A temporary pass?

Seemingly unwilling to risk the potential backlash, the Biden administration punted responsibility for figuring out how these cards would be used to the states, and by extension to the institutions doing business within those states. Earlier this month, the president asked governors to “please help” or “get out of the way” when it came to requiring vaccination for indoor activities. “I think they just need to give authority to those restaurants and businesses,” he said. Last week, relaying essentially the same message, the head of Biden’s Covid-19 response team predicted that “through vaccination requirements, employers have the power to help end the pandemic.” After all, he noted, Capital One and Discovery had taken the brave step of requiring their employees to get the jab.

In a matter of months, twisted by the feverish daydreams of right-wing pundits, an easily misplaced piece of card stock was reimagined as a highly sophisticated vaccine passport: a nefarious symbol of overreach, derided by governors as a way to force citizens to “reveal private health information” and likened by the histrionic Marjorie Taylor Greene to the Nazis’ yellow stars. By the time I texted Dr. Will about fake vaccine cards, 20 states had outright banned the already rare practice of asking for proof.

Here are some things I could do with my (again, completely theoretical) fake vaccination card, depending on whether an institution is checking my information against data collected by my state: I could go to a bar in New York or a gym in San Francisco. I could be cleared to return to the office at Facebook or McDonald’s—though I wouldn’t need it to serve behind the counter at the fast-food chain. I could return to a college’s campus, provided that college is one that has imposed a mandate and isn’t, for instance, in Florida or Tennessee, where schools have been banned from asking students for proof. I could go on a cruise to the Bahamas or fly to Hawaii without quarantining or start work at United, among the only airlines to require employees to get the jab. I could also use it to work for the federal government or in a California school, though in both cases if I chose not to flash it I’d be required to submit to Covid-19 tests once a week.

We’re so far from the vaccine mandate conjured by counterfeiters that I struggle to imagine how often buyers are really getting their money’s worth, the scenarios in which vaccines are required almost entirely dictated by a jumble of private businesses tasked with regulating one of the most pressing public health crises in 100 years. The insistence on fully reopening the country primarily through private-sector credentialing has left a chaotic landscape of institutions being responsible for enforcing what, in the absence of a real mandate, is basically just the right to make money (or spend it) indoors.

Digital passports have been in development by private-sector companies for months as scores of businesses look to develop the definitive app, a veritable vaccine certification industrial complex growing where a centralized process might otherwise be. A government survey identified 17 separate initiatives as of late March; they include efforts from Deon, a biometrics company, as well as MasterCard and IBM. New York State’s vaccine certification process—a separate entity from the New York City pass—is built on IBM’s platform and cross-references state records with a user’s birthday and vaccination date. It’s been plagued by issues, which isn’t to mention it presents problems should a person have been even partially vaccinated out of state.

Whether from true conviction or as a marketing bit, almost all of the people selling fake vaccine cards warn that soon, the government will require its citizens to submit to the vaccine. “Do not wait for them to force you to get it,” one says, invoking a future when Americans are strapped into chairs and injected with poison against their will. But the truth is so much more mundane, and murky. The Biden administration, concerned with the optics of taking a hard stance among the rampant misinformation and institutional distrust, will likely never require mass vaccination, and those $250 cards aren’t really for the government at all. They’re for the people the government has tasked with policing vaccination: the bartenders and school administrators and HR departments and third-party security companies contracted by large corporations who have suddenly become the de facto enforcers of a pressing public good.