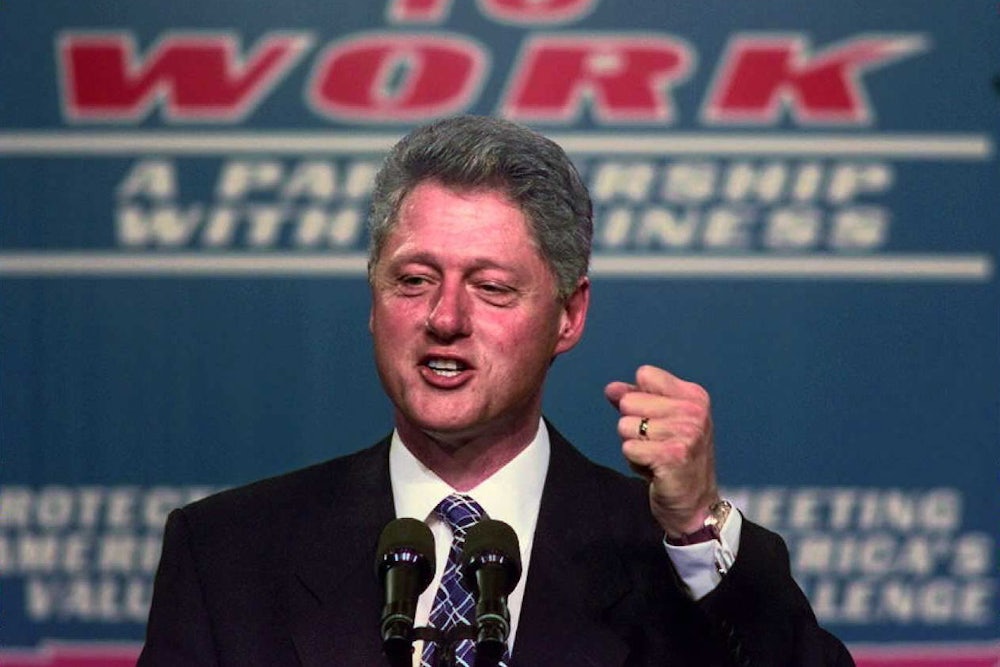

Twenty-five years ago, President Bill Clinton signed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act into law, following through on his campaign pledge to “end welfare as we know it.” He turned the Aid to Families with Dependent Children system, with its entitlement of cash assistance, into a miserly program bound tightly by reams of red tape, now known as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. The law was deeply divisive among Democrats and the party base—half of Democrats in Congress voted against it, and welfare rights activist staged protests in front of all 50 state capitol buildings—but the idea had its supporters: Eight years prior, then-Senator Joe Biden had already been calling for something like it. “We are all too familiar with the stories of welfare mothers driving luxury cars and leading lifestyles that mirror the rich and famous,” he wrote in a column. Whether true or not, he argued, they proved “the welfare system has broken down.” The poor, he insisted, needed to “work their way out of poverty.”

A quarter of a century later, his tune, and his party’s approach to poverty, may be changing. After decades of insistence that government benefits be parceled out only to those who prove they’re worthy enough, the pandemic has forced a different approach—sending pandemic aid to most Americans without erecting heavy barriers—that could create a more lasting, and desperately needed, transformation of social policy in the United States. Have we finally reached the end of the end of welfare as we know it?

Ronald Reagan spent a lot of his energy demagoguing against the system, talking about welfare queens and “strapping young bucks” who bought pricey steaks with government benefits, eventually turning welfare into a dirty word. So Clinton came up with a strategy in his climb to power: He justified reform, both during his campaign and in office, as a way to defang the issue. “Welfare is no longer a political football to be kicked around,” he said after signing the law. Once welfare “deadbeats” were forced to work, he argued, the public would start to view them favorably and be ready to open their hearts and wallets.

Those new benefits never materialized, and public sentiment instead became even stingier and more punitive after his welfare reform law passed. And yet the approach to policymaking it epitomized has run rampant throughout the Democratic party ever since. It’s the reason that poverty-alleviating tax credits like the Child Tax Credit or Earned Income Tax Credit have, until recently, been withheld from the poorest families earning little to no money—because if they weren’t working enough, they and their children were considered undeserving of help. Democrats, the supposed champions of poor Americans and the social safety net, were hell-bent on separating out the righteous and the supposedly flawed.

We’ve now had 25 years to observe whether welfare reform’s experiment worked. It depends, really, on what your definition of “worked” is. Did it help the needy find good, well-paying, lasting jobs that lifted them out of poverty, put them on stable footing, and kept them from needing government assistance? No. Did it kick a lot of people out of the program? Yes.

The bill that Clinton signed into law ended the promise of cash benefits for anyone who qualified, imposed work requirements and time limits on the program, and allowed states to throw up virtually any other barriers that they wanted. A review of the research on those work requirements in seven states found that people who were subject to them were no more likely to be employed in five years than those who had escaped them. In some of those places, the people who weren’t put through the work-requirements ringer were in fact more likely to have work. If the people who were kicked off did manage to get a job, it was likely to be a crappy, unstable one, lasting less than three-quarters of the year. In Maryland, more than half of the people pushed off the program who had a job had low, unstable, or falling earnings.

Those “deserving” of welfare didn’t do much better. The program’s block grant structure—states get a fixed pot of money to spend on it, rather than the funding increasing with need as it did under AFDC—has meant that, thanks to rising inflation since 1996, benefits have been eroded. They’re at least 25 percent lower in a majority of states.

The reforms Clinton signed into law have served to desiccate the program so that all it can offer is mere ashes, so that it’s too weak to support most who need it. Today it reaches less than a quarter of families with children living in poverty, even as extreme poverty has climbed steadily since the 1990s. Welfare performs poorly when we need it most. When unemployment doubled during the Great Recession, TANF caseloads increased just 13 percent—and in six states, they actually fell. The same thing happened when deprivation shot up almost vertically during the pandemic: The rolls fell in 10 states, all of them ones that failed to relax the program’s harsh rules.

Those rules have long served to immiserate people. In Kansas, median earnings for parents who left the program due to a work requirement were just $2,175 annually four years later, while more than one-third had no earnings at all. Eighty percent were still living in poverty. The same was true in most other places; only one location in California managed to reduce former recipients’ poverty rates. By 2008, about 20 percent of poor mothers received neither income nor cash assistance.

Work requirements in other programs are no less useless. With food stamps, the requirement has led to lower enrollment but hasn’t helped people find more work.

President Trump’s administration built on Clinton’s rhetoric and legacy and put out lengthy tomes praising work requirements and arguing they should be added to any and every government program possible. The one that the administration actually got its hands on was Medicaid. Under Seema Verma, former administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, states were invited to impose work requirements on their Medicaid programs for the first time in the program’s history.

The guise under which this was all done was promoting “self-sufficiency,” operating under the assumption that poor people need to be threatened with the loss of their basic subsistence to force them to get a job. But beyond completely mischaracterizing what it means to live in poverty—and the fact that most people who need Medicaid or food stamps do work—it was all a farce anyway. Arkansas, the only state that actually got to impose a work requirement on Medicaid recipients, kicked more than 18,000 people off the program in the span of seven months. In his budgets, Trump counted on work requirements to save billions in dollars thanks to the people he presumed would be bumped from the rolls. Republicans used Democrats’ moral rectitude as a ruse for accomplishing their longstanding goal of pushing the poor off of the government dole.

Trump’s effort is now dead in its tracks. Judges struck down state attempts at Medicaid work requirements quickly after they were rolled out. The Supreme Court was supposed to hear two states’ cases, but has tabled them with no sign of picking them back up. After President Biden assumed office, he quickly took a variety of bureaucratic steps that walked back Trump’s actions and made it clear he won’t support work requirements in Medicaid.

With the demise of Trump’s quest for welfare reform on steroids, we appear to be witnessing the demise—in fits and starts—of Democrats’ welfare reform–minded thinking. All it took was a global health catastrophe.

In the new regime, Congress has sent multiple rounds of stimulus checks to all American citizens making $75,000 a year or less to help them weather the pandemic. It increased food stamps and unemployment insurance to rates never seen before. While the programs had intentional gaps limiting their reach, these steps have still blunted the shock of the crisis to an astonishing degree. Pandemic aid will cut poverty nearly in half this year, the largest decrease in such a short amount of time the country has ever accomplished.

Democrats, prodded by the vast popularity of these measures and the party’s ascendant left flank pushing for a new approach to poverty, have gone even further on their own. After they campaigned in Georgia’s runoff election on the promise that they would send out a third round of stimulus checks, they made good, and then they expanded the Child Tax Credit to reach all poor families—whether they work or not—with more money on a monthly basis. In other words, the country has enacted a temporary child allowance for the first time in its history, something many other developed countries did long ago. For the next year, over 90 percent of families will receive a check for every child they have at home without asking if they work. This has the potential to slash child poverty in half all on its own.

Then, ahead of a looming deadline at the end of September when extra pandemic food stamps were set to expire, Biden took action to increase them by more than 25 percent from pre-pandemic levels for every recipient. It’s the largest permanent increase in the program’s history, and it came without a whiff of adding new rules or requirements to make sure the “wrong” people don’t get it.

Biden is an odd avatar for his party’s changed stance on how to help the poor. He was a fixture in the Senate throughout the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. He voted personally for the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act in 1996. But when it comes to some kinds of aid, he can sound very different today. “Families need economic relief,” he said in a statement about the expanded Child Tax Credit. Offering it to all families, even ones without income, “will ensure for the first time that even the most hard-pressed families will get at least as much support as more affluent families.” It’s not a wholesale conversion story—Biden still walks a conservative line on many of these programs—but he’s clearly had to shift his rhetoric.

The pandemic exposed how close so many Americans are to financial ruin. It also made clear that telling them to be more enterprising or self-sufficient doesn’t keep them out of destitution. Now we know for sure what does work: offering them financial assistance without forcing them to prove they deserve it. It’s never been clearer that American poverty is a policy choice. Many Democrats appear ready to make a different one.