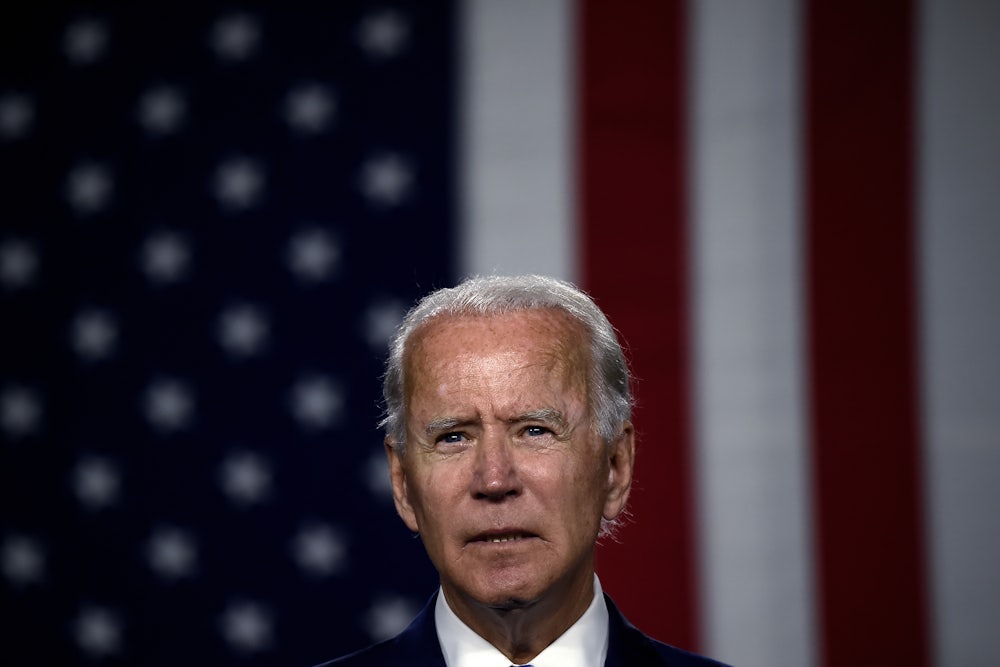

Joe Biden is keeping another campaign promise. This time, that’s not a good thing.

One of the cornerstones of Biden’s 2020 platform was to shore up democracy not only in America but around the world. In response to the rise of (sometimes Trump-inspired) authoritarianism, he pledged to “organize and host a global Summit for Democracy to renew the spirit and shared purpose of the nations of the Free World” during his first year in office, bringing together U.S. allies to “honestly confront the challenge of nations that are backsliding” and “forge a common agenda to address threats to our common values.” The White House announced on Wednesday that it will hold the first such summit virtually in December, followed by an in-person summit a year later.

But these summits are likely to do more harm than good to U.S. security—and to the cause of democracy at home and around the world. The guest list will almost certainly exclude China and Russia, inciting some measure of both anger and fear in them. Powerful states do not take kindly to being banned from international forums, and China and Russia already feel that the United States ignores their interests and is committed to undermining their regimes. The summits will only confirm as much in their eyes.

More generally, democracy promotion is no longer a useful foreign policy priority. The U.S. was successful in nurturing democracy in Japan and Europe during the Cold War. But as the political scientist Tony Smith wrote in his study of those efforts, America’s Mission, “American foreign policy was in keeping with the times as it sought to promote national security by encouraging like-minded democratic states to come into the world.” We live in very different times now. The major challenges facing this country—climate change, homegrown authoritarianism, and, yes, China and Russia—cannot be met via democracy promotion, which is liable to make solving those problems even harder.

Reflecting the post–Cold War political consensus, the Clinton administration believed that the U.S. had immense power and responsibility to reshape the world. In 2000, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright led a meeting in Warsaw, Poland, with more than 100 other countries to establish a “Community of Democracies.” The group agreed to uphold and advance democratic principles and practices. Notably, France demurred from signing the agreement. “If we’re only allowed to associate with friends who are comme il faut, who think like us, we might as well renounce the possibility of acting on any problem at all, of resolving the slightest crisis,” the country’s Foreign Minister Hubert Védrine argued. He said that Saddam Hussein and Fidel Castro showed how authoritarians could only became more entrenched when they were under siege from democratic foes. These wise objections were mostly ignored.

President George W. Bush had little interest in multilateralism, but the idea of uniting democracies remained alive in Democratic circles. In 2004, two veterans of the Clinton administration’s National Security Council, Ivo Daalder and James M. Lindsay, suggested an “Alliance of Democracies.” “The main security threats in today’s world come from internal developments within states rather than from their external behaviour,” they wrote. Daalder and Lindsay imagined the Alliance to have military capabilities fit for peacekeeping and making war.

The Obama administration didn’t adopt this idea, but it has become more attractive in foreign policy circles amid China’s continued growth and Russia’s aggression in Georgia and Ukraine, and its interference in the U.S. presidential election in 2016. America’s homegrown democratic backsliding, exemplified and furthered by Trump’s Republican Party, highlighted the global nature of the problem.

Uniting democracies in a campaign against undemocratic countries has appeal across much of the left and the Democratic Party establishment. In 2018, Senator Bernie Sanders called for a “global democratic movement to counter authoritarianism.” In a recent phone interview, Congressman Ro Khanna, another leading progressive, said, “I don’t see anything wrong with us standing for our values and trying to build alliances around our values around democratic influence.” He added: “I think there’s a way of doing it that doesn’t come off as arrogant.” Biden’s secretary of state, Antony Blinken, joined neoconservative Robert Kagan in calling for a League of Democracies back in 2019.

But all the emphasis on the commonalties of democracies has had the predictable effect of convincing nondemocratic countries that they, too, should cooperate—against the U.S.-led order. In March, China signed a major investment deal with Iran, and it has moved closer to Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. “To build small circles or start a new Cold War, to reject, threaten or intimidate others, to willfully impose decoupling, supply disruption or sanctions, and to create isolation or estrangement will only push the world into division and even confrontation,” Chinese leader Xi Jinping said about America’s moves to align democratic countries.

Promoting democracy as a superior alternative to other forms of government makes some leaders—concerned that they could one day face a democratic revolution—fearful and hostile to the U.S. They are less likely to cooperate with democratic countries on, for example, climate change, where China’s participation is essential to any initiative to reduce greenhouse gases. Shunning authoritarian countries also persuades them that they must take actions to weaken democratic countries for their own security, something Russia has demonstrated to important effect.

Rather than dividing the world based on regime type, Biden should recognize the interests of undemocratic countries—especially powerful ones—and try to convince them to align with the U.S. Some former Democratic Party officials understand this, arguing for a foreign policy aimed at splitting Russia and China. Others observe that restoring American democracy is more helpful to the cause of democracy than anything else. But that, alas, is a much harder challenge in Washington today, and hosting a global summit won’t make it any easier.