It’s hardly a secret that many House Democrats are frustrated with the infrastructure bill cooked up by a bipartisan group of senators that’s currently wending its way through the upper chamber. While the plan, which has the enthusiastic backing of President Joe Biden, has $550 billion worth of new spending baked into its pages, several members of the House Democratic Caucus have denounced the bill as woefully insufficient to address the crises facing the country—particularly climate change.

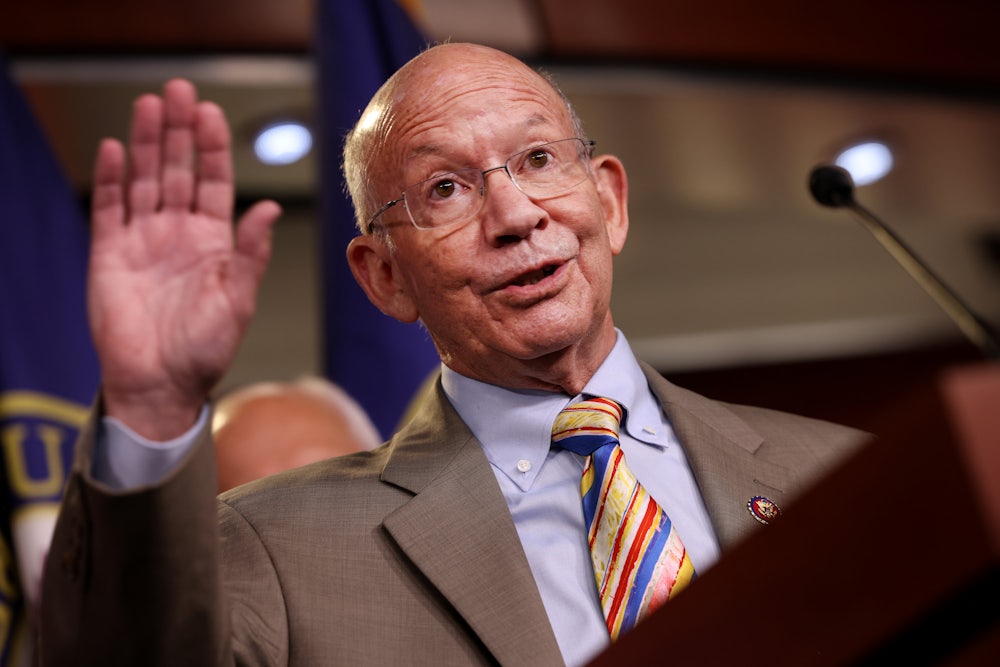

Representative Peter DeFazio, the chair of the Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, has been notably vocal in his criticism of the bipartisan deal. DeFazio told The New Republic that while he has not yet gotten the chance to read the text of the bill, which was only released late Sunday night and clocks in at 2,702 pages, previous drafts of the bill, which he characterized as too “status quo” and “highway-centric,” left him unimpressed.

“We are not moving their so-called bipartisan bill until we have reconciliation in hand passed by the Senate,” DeFazio said about the prospects of the Senate bipartisan infrastructure bill in the House. “At this point, we don’t know what will be in it, but hopefully we will fix some of the issues that have been created by this so-called bipartisan bill.”

A number of Democrats in both chambers have insisted that they are unwilling to support the bipartisan bill unless they get commitments that a larger measure, which includes more of their key priorities, follows in its wake. This second bill would necessarily have to be passed through the reconciliation process, a complicated maneuver that would allow it to be approved in the Senate without any Republican votes.

DeFazio reiterated the bipartisan deal “is not going anywhere” until House Democrats could see “what we can fix and improve in the reconciliation process before making any final judgments.” The Senate may vote on a budget resolution, which lays out the instructions for budget reconciliation, as soon as this week, but the House is in recess until the end of September.

DeFazio has proposed his own $715 billion surface transportation bill, which passed in the House in June. He argues that his measure is truly “the first twenty-first-century transportation bill,” in that it includes policies “oriented toward reducing fossil fuel pollution, electrifying the national highway network, or using alternate fuels robustly.”

The bipartisan infrastructure plan does include several climate-related provisions, including funding for more electric vehicle charging stations and improvements to the nation’s electrical grid. However, it dedicates significantly less funding to climate change than Biden originally sought and still promotes the usage of fossil fuels: It would, for instance, dedicate funding to establishing “regional clean hydrogen hubs,” one of which would generate hydrogen from fossil fuels. Natural gas and coal are also proposed as options for generating hydrogen in the bipartisan framework.

DeFazio says that he’s heartened by provisions in the bipartisan measure that would reduce the use of diesel fuels, but that these fall short of “where we need to go to save the planet.” He also noted that the provision for “reconnecting communities” in the bipartisan bill, aimed at helping disproportionately Black and poor neighborhoods divided by highways, fails to include the necessary safeguards to prevent displacement due to gentrification—which he had included in his bill.

While DeFazio has been in conversation with both Senate colleagues and the White House about adding amendments to improve the bipartisan bill, he’s largely in the dark about “what the amendment process is going to be,” and frustrated by the way the Senate’s measure, the product of lengthy negotiations between a core group of 10 senators—five from each side of the aisle—was crafted.

“Not only was the House excluded, but the chairs of the committees of jurisdiction in the Senate, for the most part, were excluded,” he said. Some committee chairs, like Senator Tom Carper of the Environment and Public Works Committee, had previously expressed concerns about the way water infrastructure provisions were negotiated in the bipartisan bill. (Carper has since endorsed the bill wholeheartedly.)

DeFazio argued that his original bill was all the better for having been passed by the House twice, after considerable seasoning from debate and amendments. His bill also included several earmarks—funding for district projects—after House Democrats ended their self-imposed ban on the practice. “We went through a real legislative process and hammered it out.”

“This is essentially a backroom deal,” DeFazio said, referring to the bipartisan bill.

Technically, DeFazio’s bill is being considered in the Senate—but only as the vehicle for the bipartisan bill. Its language will be replaced by the text of the bipartisan bill, which will have to be adopted as a substitute amendment. The bill will keep the number that it had in the House but have a new title to go along with its replacement text.

“I don’t understand the rules of the Senate, I don’t know why they chose to do that,” DeFazio said. “From what I know of their bill, I don’t want to put my name on it as an author.”