In the fall of 2018, a Snapchat video began circulating in the wealthy Dallas suburb of Southlake, Texas. It showed a group of white high school students at a party, laughing as they chanted a racial slur in unison. After the video went viral, the school district held a series of listening sessions and committee meetings around diversity and racism that resulted in a list of recommendations, which were then compiled into a “Cultural Competence Action Plan.” The plan, released last summer in the wake of the George Floyd protests, proposed a series of trainings and policies that would help “achieve student equity and inclusion.”

That report made a woman named Hannah Smith very upset. Smith had clerked for Supreme Court Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, but now she was a parent with children in Southlake’s largest school district. She viewed the cultural competence plan as evidence of a new and radical anti-racist dogma, and earlier this year she decided to run for school board to stop the district from implementing it.

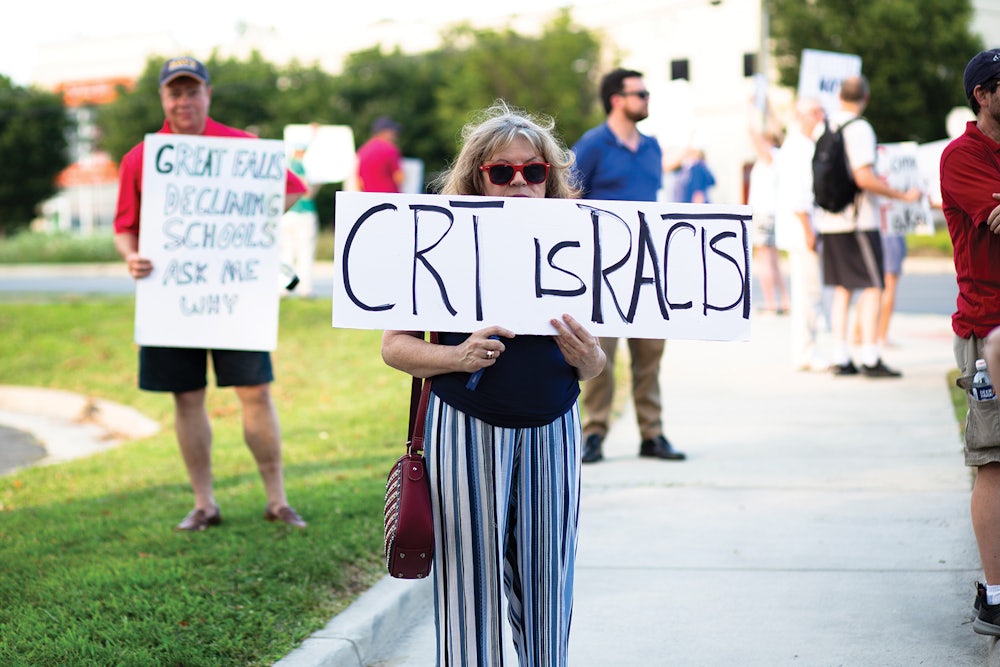

The spring school board election in the district soon became not only a referendum on “critical race theory,” the term conservatives have appropriated to describe all manner of race and equity initiatives, but also a contest for political control in a diversifying suburb. The local Democratic Party called the conservative candidates racist on social media, while the conservative bloc raised more than $200,000 from a bespoke right-wing PAC. National reporters from Fox News and NBC covered the election and the turmoil in the district.

When the polls closed in the first week of May, Smith won in a landslide, beating her opponent by more than 30 percent, as did another conservative candidate who ran alongside her on similar issues. Smith told a reporter that the results proved parents “don’t want racially divisive critical race theory taught to their children or forced on their teachers.”

The uproar in Southlake has attracted more attention in the press than almost any other scuffle over critical race theory, but the idea has become a flash point issue in dozens of school districts around the country, from the suburbs of Philadelphia and Portland to rural swaths of Utah and Florida. The furor originated in the backlash to the diversity and equity commitments that many school districts announced after the Floyd protests, but it has profound implications for the midterms and beyond. Republican donors and the right-wing media have seized on the phenomenon as a potential wedge issue for the suburban electorate, and they are now doing everything they can to invent a crisis where none exists.

Most of these tussles have followed a predictable pattern. White parents press incumbent school board members to take an uncompromising stance on a hard-to-define dogma, then react with fury when the board members struggle to respond. In some cases, like Southlake, these parents are fielding their own conservative candidates, putting control of the school board in the balance. These candidates run the gamut from engaged operatives like Smith to political newcomers: A homemaker in Rapid City, South Dakota, and a real estate agent on Long Island have both won recent elections in part by opposing the doctrine.

The issue has mobilized conservative parents even in places that do not have a school board election this year. A vitriolic battle has been raging in the wealthy D.C. suburb of Loudoun County, Virginia, since the Washington Free Beacon reported last September that the district had spent more than $420,000 on diversity training and equity assessments. The next school board elections in the county are not until 2023, but a former Trump Justice Department official named Ian Prior has led an effort to recall six members of the board before then. Prior has reportedly accrued more than 75 percent of the signatures needed for at least one of the recalls. At one recent school board meeting to discuss transgender issues, chaos erupted as parents tried to derail the meeting, resulting in at least one arrest.

It is important to note that the phrase “critical race theory” means something different in all these districts, and rarely does it have anything to do with the school of legal thought outlined by the scholar Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in the 1980s. The phrase has become conservative shorthand for any kind of diversity or equity training whatsoever, whether a lesson intended to help students dissect their privilege or a teacher seminar on implicit bias. The perceived threat in all these cases is that teachers will somehow indoctrinate students with the lessons of writers such as Ibram X. Kendi, author of the 2019 book How to Be an Antiracist, and Robin DiAngelo, who wrote White Fragility in 2018.

Although recent polls show that a large majority of Americans have no opinion about “critical race theory,” there is no doubt that some of the parent outrage over the issue is sincere. Thanks to the work of documentarian Christopher Rufo and the willing megaphones at Fox News, millions of conservatives now believe that schools across the country are teaching radical racial dogma. The freak-out over CRT comes on the heels of a yearlong conflict over school reopenings, one that pitted many white and well-to-do parents against the interests of school boards and teachers’ unions. The coincidence of these two issues has made local education a fertile ground for right-wing outrage, especially as Republicans attempt to claw back Democratic gains in the suburbs.

The upheaval in school board elections like Southlake, though, is not entirely grassroots in nature. Smith and her fellow conservative candidates benefited from tens of thousands of dollars in donations, an unusual amount for a race in which only a few thousand people voted. The same has been true in Loudoun County and in Rapid City, where a retired financier recently bankrolled a victorious slate of four conservative candidates. This influx of money has also seeded multiple advocacy organizations, which have sprung up in recent months to combat critical race theory. These include No Left Turn in Education, founded by a former social worker from outside Philadelphia, and Parents Defending Education, which maintains a shady map of ever-multiplying places where students are supposedly suffering beneath the yoke of racial dogma. (In one district, for instance, a teacher used a nonbinary “snowperson” to teach students about gender identity.)

However, the most prominent public face of this political mobilization is not a parent at all, but a childless, 34-year-old political operative named Ryan Girdusky. A native of Queens, New York, and a veteran of several Republican campaigns, Girdusky in May launched what he called the “1776 Project PAC,” intending to raise money he could funnel into school board elections this November. When I reached him over the phone in mid-June, he told me that he had founded the group after he heard that his nine-year-old cousin had learned police officers “only follow Black cars, they don’t follow white cars.” He said he had raised more than $100,000 in the three weeks since he launched the PAC and plans to raise more—enough to move the needle in multiple elections. Donations were coming at a steady trickle until Tucker Carlson highlighted the project, at which point the money started flowing from all corners. These weren’t deep-pocketed donors either, but small-dollar contributors compelled to action by the outrage machine.

It is no coincidence that this surge of political activity has arrived right after a Democrat took over the Oval Office. The moral panic over CRT is a kind of right-wing mirror image of the #Resistance movement that exploded in the first years of the Trump era, when the interests of pissed-off liberals and deep-pocketed donors aligned at a fortuitous political moment. The explicit goal of organizations like 1776 Project PAC and Parents Defending Education is to spin the fervor around critical race theory into discernible electoral gains. Once installed on local school boards, these CRT skeptics could have the power to ban diversity training for teachers, buy new textbooks, and fire superintendents they don’t like.

But the more profound possibility is that the uproar over CRT will lay the groundwork for Republican mobilization in next year’s midterm elections. Republicans believe they have identified a social issue they can use to cleave suburban voters away from the Democratic Party’s social liberalism, and they intend to exploit that issue for everything it is worth. The electoral future of their party may depend on it.