In 2005, Bill Cosby and Bruce Castor—supposedly—struck a deal.

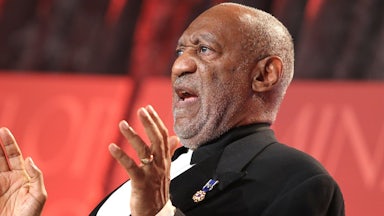

At that point in pop culture history, Cosby was still the beloved creator of Cliff Huxtable and famous for his influential standup; he was also trying to leverage his reputation as America’s TV Dad into the persona of a professional public moralist. The year before, he delivered his now-infamous “Pound Cake Speech,” berating Black Americans for failing to name or raise their children properly and for dressing “with their hat on backwards, pants down around the crack.” This hard-won reputation, however, was potentially going to be exposed as fraudulent: Cosby was being accused of drugging and sexually assaulting Andrea Constand, whom Cosby met through his alma mater and her then employer, Temple University.

The alleged assault took place at Cosby’s home in Cheltenham, Pennsylvania, in Montgomery County, where Bruce Castor was then serving as district attorney. Constand made the allegations about a year after it occurred, shortly after telling her mother; by this point, she’d returned to her native Canada, so she first spoke with the police in Ontario before being interviewed by the Montgomery County Police Department. Cosby was questioned by the Cheltenham Police. He claimed his encounter with Constand was consensual.

Castor never interviewed Constand. He never even met her. About two weeks after Constand spoke to the police, California lawyer Tamara Green came forward on The Today Show to say that in the 1970s she, too, was drugged and sexually assaulted by Cosby. A week after Green’s television appearance, Castor announced he would not be pursuing charges against Cosby. He said that “insufficient credible and admissible evidence exists upon which any charge against Mr. Cosby could be sustained beyond a reasonable doubt.”

This is when—so Castor would later claim—he made a deal with Cosby. Castor says he promised Cosby that he would never be prosecuted in the Constand case. Castor (again, later) said he extended this pledge so that Cosby would “testify freely” in Constand’s civil suit, secure in the knowledge that whatever he said could not be used as evidence against him in a criminal proceeding. (Or, as Cosby’s attorneys would later frame it, the deal deprived Cosby of his Fifth Amendment rights, making it so he could not refuse to answer any questions during the deposition.) It’s worth noting that, at the time Castor issued his press release about not pursuing charges against Cosby, Constand had yet to file her suit. In a statement released yesterday, Constand and her attorneys wrote, “We were not consulted or asked our thoughts by Mr. Castor concerning any agreements concerning immunity or anything, and we were not made aware if there were any such discussion.”

Constand’s eventual civil suit against Cosby charged him with battery, assault, and intentional infliction of emotional distress. Thirteen women, all identified as Jane Does in court documents, alleged similar assaults. That fall, Cosby was deposed, during which time he revealed an explosive piece of evidence, arguably the crux of the case that eventually sent him to prison: He admitted on the record to obtaining drugs for women with whom he wanted to have sex.

It’s hard to overstate the impact this testimony had on the Bill Cosby case. In the court of public opinion, it instigated a swift and extraordinary turn against the comedian. Even President Obama commented on the matter, averting specifics but saying, “If you give a woman, or a man for that matter, a drug and then have sex with that person without consent, that’s rape. And I think this country, any civilized country, should have no tolerance for rape.”

Though its inclusion was contested mightily by Cosby’s legal team, this testimony was deployed by the prosecution in both of Cosby’s criminal trials, which I covered for ThinkProgress. It seemed that any reasonable person could agree that it removed all doubt from the situation. This was the smoking gun that sexual assault cases virtually never have: as close to an on-the-record confession from the assailant as one was likely to find.

Armed with this extraordinary piece of evidence, District Attorney Kevin Steele, who had by this time replaced Castor in office, recruited 19 women who alleged Cosby had assaulted them to serve as “prior bad acts” witnesses. Of those 19, the judge in Cosby’s second criminal trial allowed five to take the stand. (At the first effort, which ended in a mistrial, only one prior bad act witness was allowed to testify.) This second trial hit as the #MeToo movement was cresting, as multitudes of survivors were emerging from the excruciating isolation of their trauma and discovering that they were not alone—they weren’t the only one subjected to Harvey Weinstein’s casting couch, to Larry Nassar’s abuse masquerading as medicine, to that teacher, to that coach, to that boss.

There was horror in numbers, in just how many scores of survivors it seemed to take for one abuser to be exposed and stopped. There was, sometimes, guilt at what could have been prevented if those who came before had been able to speak up, or be believed, in time to protect those who came after. But there was also, finally, power. There was some sense of community, even what many Cosby survivors told me they considered a “sisterhood.”

The five women who testified to aid Constand’s case had no route to justice on their own; the statutes of limitations in their respective cases had all expired. Despite the insidious, persistent myth to the contrary, victims of sexual violence have everything to lose when they speak out and very little to gain. Most never report. But this time seemed different. Because it seemed like times were different. It was simultaneously agonizing and encouraging. These women opened themselves up to the world, to aggressive and potentially retraumatizing cross-examinations, and told the truth.

Was it worth it? At the time, it surely seemed so: Cosby was found guilty on all three felony counts of aggravated indecent assault, and sentenced to three to 10 years in prison.

He served just two years and nine months. Cosby is now a free man. He is no longer obligated to register as a sexually violent predator. And he cannot be tried again on these charges. According to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, in a ruling that came down yesterday, there shouldn’t have been a trial at all, because the criminal trial violated the nonprosecution deal struck by Cosby and Castor. But the proof that this deal ever existed is dubious.

We are left with a situation in which a man who has been credibly accused by 60 women of drugging and sexually assaulting them; who was convicted in a court of law by a jury of his peers; who admitted, on the record, to obtaining drugs, including quaaludes, for the purpose of giving them to women with whom he wanted to have sex is now being released from prison because of some promise Bruce Castor supposedly made, for which no contemporaneous documentation can be found.

The most charitable description for what the Pennsylvania Supreme Court has done is to say it’s made a hash of the matter. Here at this late date, it’s diminished the compelling and credible testimony of numerous survivors in favor of an account from the case’s two most unreliable narrators, Bruce Castor and Bill Cosby.

What we have here—can you believe this shit?—is a classic he said, he said.

In case you’ve forgotten what the prevailing attitudes regarding Cosby were in 2015, here’s a refresher: In October 2014, Hannibal Buress’s standup set about Cosby went viral (“... you rape women, Bill Cosby, so turn the crazy down a couple notches”), kicking off a wave of media attention around the allegations against the star. Accusers came forward in a trickle, then an onslaught; by May, more than 40 women had stated publicly that they’d been victims of Cosby’s violence. During that year’s Golden Globes monologue, hosts Tina Fey and Amy Poehler joked that Sleeping Beauty “just thought she was getting coffee with Bill Cosby.” That summer, the deposition from Constand’s civil suit was unsealed, its contents revealing a chilling portrait of Cosby as a calculating predator who used sedatives in his relentless pursuit of young women.

The national mood and public opinion about Cosby had shifted so dramatically over the decade prior that Castor—who, in 2005, issued a press release about not pursuing charges against Cosby—was, in 2015, running for district attorney on a platform of “I’ll get Cosby this time!” His opponent, Kevin Steele, ran TV ads calling Castor “a former DA who refused to prosecute Bill Cosby.” It was not a great time to be running for office as the guy who let Cosby go. Case in point: Castor lost.

So it is in this awfully convenient and questionable climate that Castor, for the first time, mentioned in writing that he had struck a nonprosecution deal with Cosby. Judge Thomas G. Saylor, who wrote the dissent to yesterday’s Pennsylvania Supreme Court decision, points out this obviously suspect timing. “The first time [the alleged promise not to prosecute] was reflected in any written form was in Castor’s 2015 emails. This alone calls its existence into question.”

The notion that Castor made this deal to help Constand in some valiant effort to make sure her civil suit succeeded also strains credulity, not least because civil suits are not, in fact, the purview of the district attorney. Also: Castor and Constand never spoke to one another! Or met!

As Carrie Goldberg, a personal injury lawyer specializing in sexual violence, wrote on Twitter, “Granting Cosby a non-prosecutorial agreement made did not help [Constand’s] civil case. Her civil case would have been served even better by him pleading the 5th and having the jury draw negative inferences.… Prosecutors play NO role in civil claims. Castor is not a party to the civil case.”

Saylor put it this way:

“Castor wrote those emails in the midst of a political campaign for district attorney, after he had learned of a renewed investigation into the case. He would face negative publicity if criminal charges were filed before the election. He tried to discourage then-District Attorney Ferman from filing charges by rewriting history in light of the political facts on the ground in 2015. His testimony at the hearing was also inconsistent with his 2005 press release, his statements to journalists over the years, and irreconcilable with his September 2015 emails to District Attorney Ferman.”

You don’t even have to look to the dissent to see that the deal that was supposedly struck between Cosby and Constand was underpinned by spurious documentation. “In fact, no one involved with either side of the civil suit indicated on the record a belief that Cosby could be prosecuted in the future,” reads the Pennsylvania Supreme Court opinion. “DA Castor’s decision was not included in any written stipulations, nor was it reduced to writing.”

In early 2016, as Cosby’s first criminal trial approached, his legal team argued that Cosby only spoke so candidly in that bombshell deposition because he thought he was immune from prosecution thanks to his deal with Castor, and that said deal needed to be upheld by all Montgomery County district attorneys for the rest of time. A judge disagreed, ruling that the deposition was fair game. The deposition made it into both trials.

But in its ruling yesterday, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court overrode that decision because “we are not bound by the lower courts’ legal determinations that derive from those factual findings.” Instead of being bound by fact, they are loyal only to “the principle of fundamental fairness that undergirds due process of law in our criminal justice system[, which] demands that the promise be enforced.” It is taking Castor’s word for it—despite Castor’s general untrustworthiness and the extremely flimsy evidence supporting his word—and has determined that the promise itself created a constitutional obligation not to prosecute.

Though Castor didn’t bother contacting Constand in 2005, he heard from her when she sued him for defamation in October 2015, just before the election that Castor would go on to lose. The month before, her attorneys published an open letter to Castor, demanding an apology from him for accusing her of making inconsistent statements back in 2005, essentially blaming her for not being a reliable enough witness for his office to bring charges against Cosby. Her lawsuit alleged Castor had made her “collateral damage for his political ambitions” by smearing her in the press and accused Castor of working to “thwart” the reopened investigation into her case by telling a local reporter that “from a political standpoint, it looks really bad to move on Cosby before the election.” After that interview came out, Constand’s attorneys said, the investigation “stopped cold.”

Just to round out the Bruce Castor Cannot Be Trusted portion of the proceedings here, let’s review some of the latest bullet points on his résumé. Earlier this year, he defended President Donald J. Trump—a man who lies so brazenly and often that the qualifier “pathological” feels quaint and useless and who, it always bears repeating, has been credibly accused of sexual violence by at least 20 women—at his Senate impeachment trial over the allegations that he incited the January 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol.

During that trial, Castor’s rambling, nearly incoherent work was described by presidential historian Michael Beschloss as “the most incompetent legal representation of any modern president, incumbent or otherwise.” Castor and his defense team accused the rioters of bringing “unprecedented havoc, mayhem, and death” to the Capitol, saying those rioters ought to be on the receiving end of “robust and swift investigation and prosecution.” But now—plot twist!—Castor is defending two of the rioters. And this is the guy who not only says that we must trust him when he says he made a super-secret special promise with Cosby but also holds that Andrea Constand was not a credible witness.

The other person whose credibility we are being asked to rely on is Bill Cosby. Bill Cosby—who still insists that every single sexual encounter he has ever had was consensual. I repeat: More than 60 women have publicly, credibly accused Cosby of sexually assaulting them. Seven of those women have testified as such under oath, on pain of perjury, during Cosby’s criminal trials. Bill Cosby’s name is essentially pop cultural shorthand for drugging and raping someone. If you’re at a party and you hand your drink to a friend while you go pee and say, “Can you watch this for me so I don’t get Cosbied?” nobody thinks what you mean is, “Hold my beer so no one tries to sell me Jell-o.”

Did the Pennsylvania Supreme Court not find it a little suspect that these men—a district attorney and a wealthy, powerful celebrity who availed himself of the best legal counsel money could buy—allegedly made this handshake deal over immunity and left it at that? Nobody thought they’d want a contract for this extremely high-stakes situation? Once more to Saylor: “That an experienced district attorney, a veteran criminal defense attorney, and several competent civil attorneys would fail to leave a paper trail of such a significant agreement beggars belief.”

As a thought experiment, let’s just say Castor and Cosby really did make a deal. Here’s the thing: In Pennsylvania, a prosecutor needs to ask the court for permission to officially grant immunity from prosecution. Castor never did. Goldberg tweeted about this, as well: “There is an actual PA law that formalizes immunity agreements—42 PA.C.S. 5947. It requires an actual court order.”

So if Castor really wanted this so-called deal to be kosher, he would’ve gotten a court order and made it official. But he didn’t.

In her victim impact statement, Andrea Constand wrote about the toll of Cosby’s alleged assault on her life and her family. She was only 30 years old at the time, “a young woman brimming with confidence and looking forward to a future bright with possibilities.” Now, she said, she’s “unable to heal fully or move forward. Bill Cosby took my beautiful, healthy young spirit and crushed it.”

She wrote about the responsibility she felt as the only one—the only one with a case against Cosby that hadn’t expired, one of the only sexual assault survivors whose case could shape how other survivors felt about themselves.

“I have often asked myself why the burden of being the sole witness in two criminal trials had to fall to me,” she wrote. She knew that how she was portrayed “would have an impact on every member of the jury and on the future mental and emotional well-being of every sexual assault victim who came before me. But I had to testify. It was the right thing to do, and I wanted to do the right thing, even if it was the most difficult thing I’ve ever done.”

Constand put herself, and her family, through a nearly never-ending ordeal for the sake of justice. The women who testified alongside her did the same. But Castor could not be bothered to file some paperwork. And Cosby still walks.

Something about this particular technicality just wrecks me. It makes me think about every sexual assault survivor who is ripped to pieces for not being some perfect, rule-following, box-checking victim; who is dismissed as a liar or an opportunist because she didn’t dial 911 the second her rapist rolled off her, because she didn’t behave exactly the way someone who doesn’t know anything about sexual violence expected her to; who, in the aftermath of someone else doing something so, so wrong to her, finds herself villainized at every turn for not doing every single thing just right.