Savvy guys like Matt Yglesias, the newsletter writer and former Vox and Slate blogger, sometimes critique bad political punditry by pointing out that it often boils down to saying things like, If politician [x] wants to win, they should adopt all of my preferred policies. It’s a fair point: A lot of bad electoral analysis from across the political spectrum does follow that pattern.

But of course, even savvy guys sometimes make related fallacious arguments, like, Candidate [x] pulled off this victory because they adopted the messaging strategy I currently deem the savviest. Or even, This specific, overdetermined local election result exposes a fatal flaw in the strategy of the left/progressives/Democrats.

Just after 11 p.m. on Tuesday, with only a portion of the ballots unofficially tallied, Yglesias announced that the early results in the Democratic primary for the next mayor of New York should cause the “progressive nonprofit world” to “reflect on the extremely limited constituency for the Maya Wiley brand of politics.” (Wiley is the candidate currently in second place.) The journalist Josh Barro, on the other hand, explained the election by crediting Eric Adams’s electoral performance to his focus on crime, something that politicians have focused on forever but that is now rebranded as a counterintuitive strategy precisely because the left has had some electoral success undermining that message. Since the polls closed, I and every other too-online follower of election news have seen countless other similarly broad and vastly overgeneralized interpretations of this primary election.

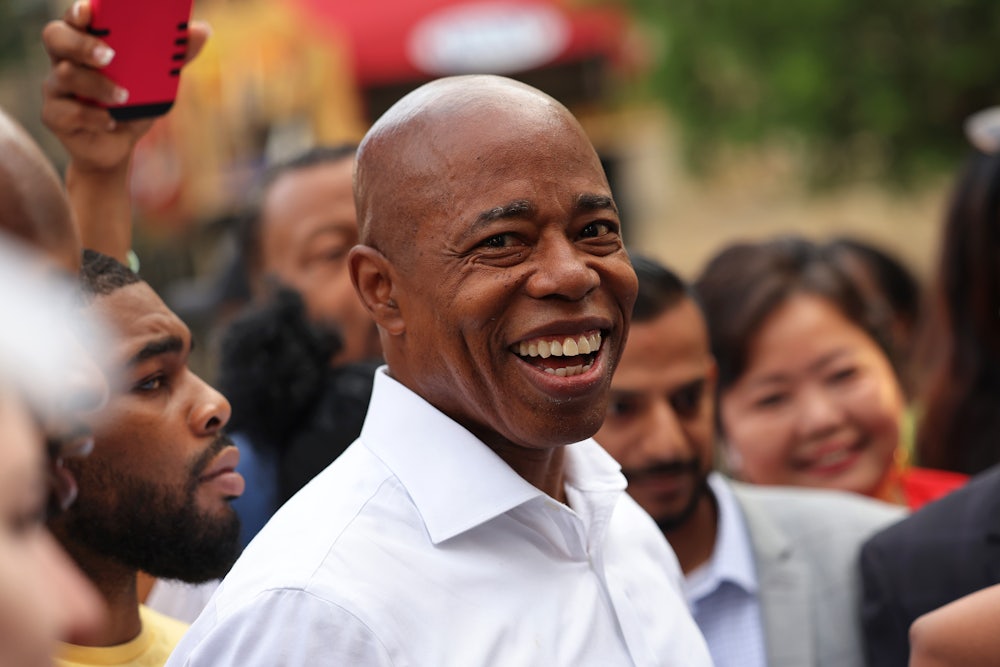

This is where the election stands: With early results of the in-person vote in, thousands of absentee votes yet to be opened, and multiple rounds of ranked-choice votes to count, Adams—a former New York state senator and police officer who is now Brooklyn borough president—is leading the race for the Democratic nomination for mayor of New York, with around 31 percent of the vote, compared to 22 percent for Wiley, the candidate from the aforementioned “progressive nonprofit world.” This is the result that so many people, Tuesday night and through all of Wednesday, decided to hang entire takes on, arguing to audiences of people who already agree with them that anyone who disagrees should step out of their narrow ideological echo chambers.

One common thread in these takes is a sort of satisfaction that an amorphous faction of The Left had been rebuked, and that they were unprepared for it. To wisely intone (as New York Times election-knower Nate Cohn also did Wednesday) that “the Democratic Electorate on Twitter is not the same as the Actual Democratic Electorate” is to imply that the “Democratic Electorate on Twitter” live in a bubble and think everyone agrees with them, unlike the sober Elections Expert who knows that, actually, it’s all More Complicated than that. In actuality, no one following the race closely, very much including the “Democratic Electorate on Twitter,” failed to see Adams coming or doubted the strength of his coalition and message.

It is actually a banal truism that New York has a lot of fairly conservative voters who are also Democrats, because the Democrats are the only game in town (this is common in American urban politics, in fact, which is why American urban politics would likely be more democratic and accountable if it could somehow adopt European-style multiparty elections and coalitions). In a piece that went viral on Twitter shortly before the election, the writer Alex Yablon shrewdly mapped New York City politics not to the self-identified worldviews of Democratic voters (most of them, including many conservatives, would likely label themselves liberal) but onto homeownership. For obvious material reasons, homeownership in an economy built on appreciating asset values leads fairly directly to conservative positions on a variety of issues. A candidate who can adopt conservative positions while still credibly claiming to be progressive has an obvious advantage in urban politics, and indeed those candidates win elections basically all the time in cities across the country. Unfortunately, this slightly more sophisticated analysis does not quite juice engagement as much as “loser nonprofit world liberals got stomped by the anti-crime candidate, and Rose Twitter never saw it coming.”

In real life, Eric Adams was the law and order candidate and the police reform candidate. He has a multidecade record of making headlines attacking the leadership of the NYPD. He was also rather explicitly the candidate of what centrist pundits typically castigate as “identity politics.” That makes total sense, too, because he was running in a Democratic primary with a massive Black electorate. He was thus able to run as the most conservative candidate in the field and credibly present himself as a true progressive Democrat with endorsements (both official and tacit) from other Democrats representing most of the ideological spectrum of New York Democrats (including even a few nominally on “the left”!) In other words, if you told me last year that a Black Brooklyn elected official would win full-throated support from the New York Post and also run ads featuring beloved actor and longtime anti–police brutality activist Danny Glover, I would assume that that candidate would be the overwhelming favorite to win, with or without adopting any particular messaging I could possibly conceive, and regardless of the messaging flaws of his opponents. The fact that Adams instead won a bit less than a third of the vote in the first round of ranking, and still faces the possibility of losing in later rounds, suggests he may actually be a flawed candidate or one who emphasized the wrong message.

Pundits could conceivably chalk Adams’s lead up to a number of reasonably credible explanations. It could be a sign that “the party decides.” It could suggest that while name recognition remains one of the most important factors in elections, liberal voters continue largely to reject “celebrity” candidates. It could, as Yglesias suggested, point to the limits of Wiley’s MSNBC-inflected “nonprofit world” politics, but those limits have been apparent for some time now, including to the city’s organized left (there are reasons she only became their candidate after other candidates on the progressive track imploded for other reasons). Alas for my profession, most of the lessons pundits can really draw from this partial result apply mainly to politics in New York and perhaps a handful of other very large and demographically similar cities.

I doubt many national-level Twitter and Substack pundits could have told you very much about Eric Adams a year ago. For them, Adams perhaps seems like he came out of nowhere. But that is simply not the case for the sort of people who always vote in local Democratic primary elections. Before forming takes on his messaging and extrapolating nationally from there, one should understand how little persuasion Eric Adams had to do at all. He and his allies turned out his base in an election with relatively small overall turnout, against a field that no one was very satisfied with. (When will the clueless left learn to field candidates with long political careers and many popular and influential allies?)

What happened yesterday in New York was the most boring and predictable outcome—one that anyone who has even a glancing familiarity with the city’s politics would have predicted last month or even two years ago. It’s not an outcome many left-wingers and progressives wanted to happen, but contrarians looking to dunk on their left flank should stop intentionally conflating undesired outcomes with surprising ones.