When a pro-Trump mob attacked the Capitol on January 6 to prevent Congress from finalizing President Joe Biden’s victory, many Republicans were willing to say that it was Bad. Mitch McConnell denounced it as a “failed insurrection” that had been “provoked by the president.” GOP members of Congress who’d planned to object to the certification of the Electoral College votes backed down, having come face-to-face with the consequences of their actions. Some of them even called for the president’s resignation.

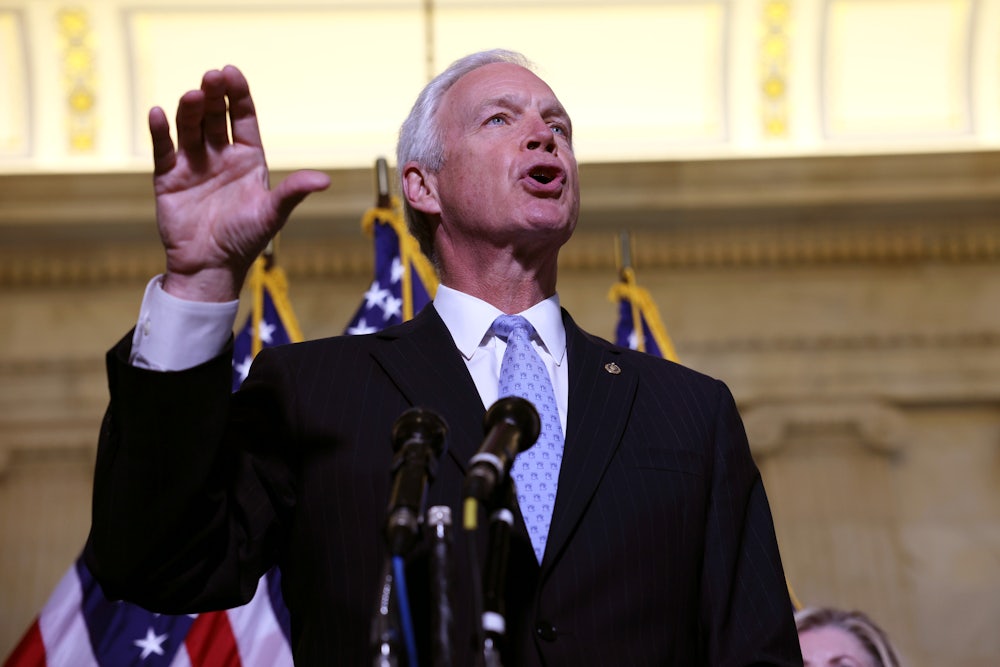

Their stance has shifted over the past few months. Instead of the free and open denunciation of the Capitol riot, a growing number of Republican officials are softening their position from “It was Bad” to, at worst, “It was Not Good” or “It was … less than ideal.” Foremost among them is Wisconsin Senator Ron Johnson, who freely admitted to Fox News over the weekend that he wanted to rewrite history to the rioters’ benefit. “I think it’s extremely important to create an accurate historical record of exactly what happened so the false narrative that thousands of armed insurrectionists doesn’t last,” he said.

The rioters assaulted dozens of Capitol Police officers, ransacked congressional offices, vandalized artworks, chanted, “Hang Mike Pence,” and built a makeshift gallows nearby. Johnson said he didn’t “condone” them for breaching the Capitol but nevertheless claimed that they “weren’t rioting.” He noted that many of the protesters were “staying within the roped lines in the Rotunda” and seemed to be “in a jovial mood.” Johnson denied that the attack on Congress amounted to an insurrection.

Johnson isn’t alone. Georgia Representative Andrew Clyde described the rioters’ behavior inside the Capitol as akin to a “normal tourist visit.” Jody Hice, another Georgia representative, argued that it was Trump supporters “who lost their lives that day,” imparting a sense of victimhood upon the rioters. South Carolina Representative Ralph Norman suggested last month without evidence that the Trump supporters who attacked the Capitol may have been left-wing agitators—a theory also floated by Johnson but abandoned after he decided to start defending the rioters outright. On Tuesday, 21 Republicans in the House voted against awarding a medal of valor to the police officers who protected the Capitol; Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene said she voted against the measure on the grounds that the bill referred to the events of January 6 as an “insurrection.”

Meanwhile, law enforcement agencies continue to investigate the riots and make arrests; numerous trial proceedings against those who illegally breached the Capitol that day are wending their way through the courts. What would these Republicans suggest be done with the rioters, if they had the ability to decide? Pardon them and commute their sentences? This is a hypothetical concern for now, but it represents a larger fear: If Republican lawmakers can move from open condemnation of January 6 to a mixed indifference toward it in less than six months, there’s ample reason to believe that sometime between now and 2024, they’ll have revised their position to a tacit or open support of something similar.

These lawmakers’ perceptions are a reflection of the conservative mainstream. A Reuters/Ipsos poll in April found that 55 percent of Republican voters said yes when asked by pollsters if left-wing agitators were responsible for January 6. This isn’t actually true, and there’s little reason to think that Republican voters generally believe this. A Quinnipiac survey last month, for example, found that 74 percent of Republicans wanted to move on from the attack and focus less on what happened. If Republicans sincerely believed leftists were responsible for January 6, why would they want less scrutiny of the day’s events?

Fox News’s Tucker Carlson, who recently called immigration “the most radical possible attack on the core premise of democracy,” often downplays this actual attack on American democracy. He has disputed that January 6 amounted to an insurrection and insinuated that some of the rioters were political prisoners. On the three-month anniversary of January 6, Carlson gave an extremely favorable spin on the rioters as he sarcastically mocked coverage of the attack.

You saw what happened. It was carried live on television, every gruesome moment. A mob of older people from unfashionable zip codes somehow made it all the way to Washington, D.C., probably by bus. They wandered freely through the Capitol, like it was their building or something. They didn’t have guns, but a lot of them had extremely dangerous ideas. They talked about the Constitution, and something called their rights.

Some of them made openly seditious claims. They insisted, for example, that the last election wasn’t entirely fair. The whole thing was terrifying, and then, as you’ve been told so very often, they committed unspeakable acts of violence.

The result is a strange mishmash of claims and beliefs among the right: that the tragedy of January 6 may have been the work of left-wing provocateurs and that it shouldn’t be investigated further by Congress, that the ongoing criminal investigations mean a bipartisan commission is unnecessary and that those criminal investigations reflect a purported anti-Trump zeal by the Biden Justice Department, that what happened on January 6 should be condemned and that those responsible for it shouldn’t be held accountable.

This obfuscation isn’t new, especially in the Trump era. When someone mailed pipe bombs to prominent Democrats and major news outlets ahead of the 2018 midterms, right-wing media figures immediately argued that it was a liberal hoax or false flag operation of some kind. Federal agents later arrested an avid Trump supporter in Florida for the attempted attacks. As I noted at the time, there’s a deeper history of this aggressive denialism in American politics: When the first Ku Klux Klan emerged in the 1870s, many of its sympathizers denied the abundant evidence of its existence and cast Southern whites as the true victims of Reconstruction.

What makes this shift in conservative views on January 6 so troubling is that the underlying grievance that drove January 6 remains intact. More than six in 10 Republicans still wrongly believe that the election was stolen from Trump, a belief he is more than willing to inflame during his postpresidential retreat to Florida. Arizona Republicans’ pseudo-audit of the 2020 results over the last few months, and the widespread interest it evoked among other GOP state lawmakers, shows that the party itself hasn’t moved on, either. Even congressional Republicans are drifting toward Trump on the Big Lie: The House GOP ousted Liz Cheney from her number three leadership slot for not lying about the election last month, installing Trump devotee Elise Stefanik in her place.

It’s worth noting that Trump’s efforts to overturn the 2020 election before January 6 mainly failed because a sufficient number of elected officials in key positions refused to go along with them. Democrats held key governorships and secretary of state positions in many of the states Biden won. But GOP state officials in Arizona and Georgia also resisted pressure to interfere with the official count or declare it fraudulent. Republican lawmakers in Michigan and Pennsylvania ultimately declined a Hail Mary bid to change the electoral votes through legislative action. The Supreme Court’s conservative majority rejected out of hand a stupendously anti-constitutional lawsuit by Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton to overturn Biden’s victory in six states.

Trump, for his part, will continue to insist that the 2020 election was stolen. He will likely spend the next few years doing what he can to punish Republicans like Georgia’s Brian Kemp and Brad Raffensperger for not helping him undermine the outcome. If he runs again in 2024, he will almost certainly be the party’s nominee. If the past is prologue, he will once again try to delegitimize the election in advance and fight the outcome if he loses again.

This time out, however, he would enjoy even deeper support among the GOP for these thuggish and authoritarian tactics—and possibly even an open embrace of the type of violence that nearly made January 6 a greater tragedy than it already was. The GOP’s shift from vilifying the riots to revising their history suggests that it might now be susceptible to a deeper and more incurable illiberalism. If so, the only question that remains is whether the GOP will succumb to this disease alone or take the rest of the Republic down with it.