A few years ago, attending a tech conference that catered to an industry-friendly audience, I listened as a venture capitalist praised the upcoming possibilities for growth in the U.S. health care market. This V.C., who invested mostly in bioscience companies, was exultant at the possibility that personalized genetic mapping and other innovations would allow people to spend even more money on health care, purchasing everything from customized nutritional supplements to advanced targeted cancer treatments. The result would be great profits for people like him and the companies in which he invested, as health care would become as personalized and consumer-driven as shopping for clothes online.

Consumer choice and bespoke vitamin packets with your name printed on them are not solutions to much of anything in American health care; fancy artificial intelligence diagnostic tools and online pharmacies have not solved the essential problem of provisioning and accessing care. Yet Silicon Valley acts as if it is an innovation or two away from solving the problem—made glaring and overwhelming during the Covid-19 pandemic—of furnishing something like universal health care.

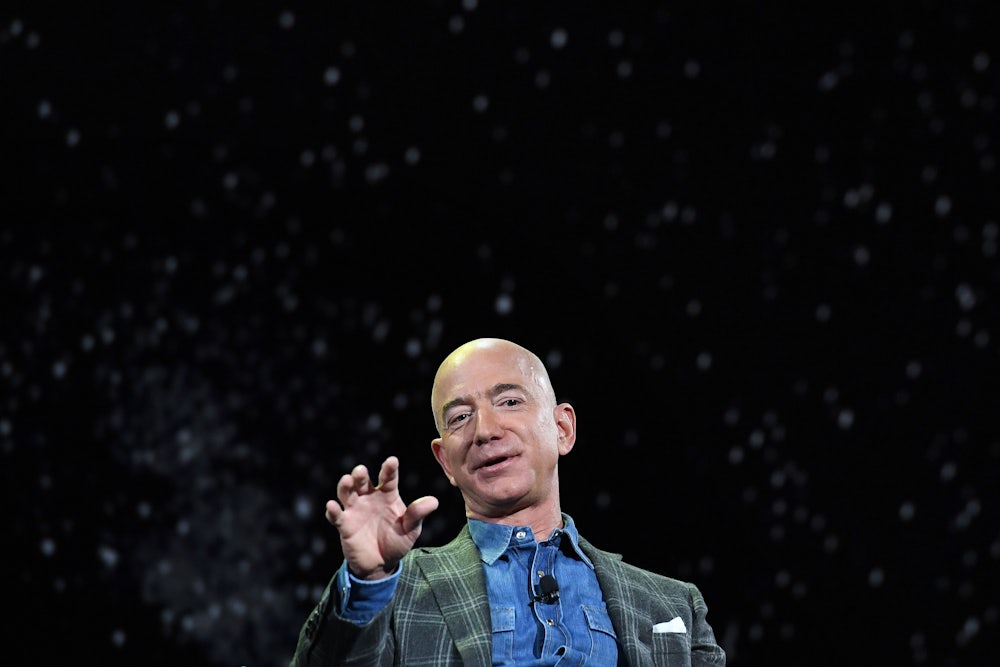

Whether it believes its own rhetoric—or just smells another profit opportunity—the tech industry shows little sign of slowing its march into the world of commercialized medicine. Following years of rumor and hype about its health care intentions, it was reported this week that Amazon may soon launch brick-and-mortar pharmacies. Amazon also has a forthcoming public health care offering known as Amazon Care, in which it will offer telemedicine and in-person care. That program has already been available to Amazon employees for about 18 months.

Amazon isn’t alone. Microsoft has a data initiative with Providence St. Joseph Health, which operates dozens of hospitals in the United States. In 2019, Google signed a deal with the Mayo Clinic to manage and parse health records for “insights,” explaining that cloud computing and data analytics would provide better performance. Google also reached an agreement this week with HCA Healthcare, a large hospital chain, to mine patient records to develop algorithms that might improve care. Like many Google initiatives, it’s essentially a data grab. “Data are spun off of every patient in real time,” HCA’s chief medical officer told The Wall Street Journal. “Part of what we’re building is a central nervous system to help interpret the various signals.” This “nervous system” may help hospitals better handle digital medical records or diagnostic data, but it will also serve to implant Google, or companies like it, at the digital heart of operations for medical facilities all over the country.

And in the case of Amazon, this isn’t its first effort to “disrupt” health care. Earlier this year, a health care consortium known as Haven, which was funded by Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway, and JP Morgan, folded after accomplishing nothing in three years. At the time, a spokesperson told CNBC that Haven produced useful insights that would yield advantages for its partners’ individual initiatives: “The Haven team made good progress exploring a wide range of health care solutions, as well as piloting new ways to make primary care easier to access, insurance benefits simpler to understand and easier to use, and prescription drugs more affordable.”

This bloodless technocratic language should sound familiar: It’s the same attitude exhibited by the V.C. at that tech conference a few years back, and it is totally removed from people’s fundamental material needs. There’s talk of ease of access and furnishing better care but little discussion of what really matters: universal care that’s free at point of service. Nor do Silicon Valley’s would-be health care entrepreneurs evince much concern for concepts like health care justice, reproductive rights, or repairing systemic inequities. New algorithms may hold out promise for processing masses of medical images, but even these supposed breakthroughs come with deficiencies, often owing to biased training data. One New England Journal of Medicine study found that algorithms used in a variety of medical contexts can reinforce racial biases, compromising care. In this arena, “disrupting” health care doesn’t mean repairing a broken system; it means leveraging that system’s vulnerabilities to innovate new delivery systems and new forms of profit.

That V.C.’s dream of Americans spending more of their income on health care may have been ghastly in its insensitivity to people’s real concerns, but it remains a sad market reality. U.S. health care spending grows consistently, reaching $11,582 per person in 2019. Insurance premiums—and insurance company profits—have risen far faster than workers’ wages. One study found that Americans now spend double on health care what they did in the mid-1980s. Tales of Americans refusing health care for fear of bills—passing on an ambulance ride or delaying treatment for an acute condition—are legion. Medical bills remain one of the leading contributors of consumer bankruptcy—a novelty for large swathes of the world where no one must pay for medical care, much less risk bankruptcy.

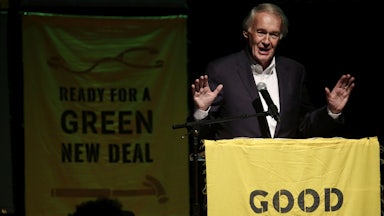

The solution, as it’s long been, is clear: a universal health care system that provides free care. The principle is as simple as the fire department or the local library—shared services that everyone pays into and are free when they need them—but it’s one that would likely be lost on most politicians today. (If public libraries were proposed now for the first time, how many Democrats would join Republicans in voting against them?)

Bracketing social justice concerns for a moment, advocates and policy experts have known for years that universal, free, government-provisioned health care would save consumers and the government money. On neoliberal logic alone, it makes sense—which is why venture capitalists fear it. As a result, the tech industry, seeking its own share of the rentier’s pie, would rather speak of novel public-private partnerships and unexpected insights garnered from parsing millions of private medical records. These initiatives do nothing for a diabetic patient struggling to afford insulin or a new parent drowning under five-figure medical bills. There is only one way to solve our broken health care system: make it accessible and free for everyone. By America’s hypercapitalist standards, that would be an innovation beyond anything we’ve yet seen.