The ultraconservative hijack of the Supreme Court, enabled by Mitch McConnell’s chicanery and President Donald Trump’s assent to Federalist Society–blessed nominees, has left liberals and Democrats flummoxed by a justifiable dread. Now comes the question: What is to be done about it? Lacking agreement on a credible path to reverse the prospect of a judiciary hostile to landmark judicial and legislative achievements, they have spent months squabbling over various “court reforms”—essentially, institutional makeovers—that are unlikely either to pass into law or, on the chance they do, to reliably advance liberal goals or interests.

It’s possible that all the saber-rattling might, for a time, make a difference. Even if the current court reform debate yields no concrete legislative results, the noise it generates may convince the court’s conservatives that discretion should be their guide star, and that trimming their sails and tacking toward the center might be the best course of action. But at some point, talk without action threatens to recast the drive for judicial reform as a paper tiger, which might in turn embolden the right’s grand reactionary design.

Perhaps the most damaging aspect of the current preoccupation with court makeover confections is that it has distracted liberal and Democratic leaders from the real challenge they must meet to regain traction in the war for the courts: to come up with a politically marketable picture of what a liberal-leaning judiciary would look like and do. They need to roll out an agenda for the judiciary that matches what the nation requires and most voters want. Moreover, that agenda must be packaged in a credibly constitutional vision—an undertaking that, unlike their adversaries on the right, contemporary Democrats and liberals have never seriously attempted.

Now they have no choice. Since any Democrat-sponsored court-related proposal will inevitably be perceived as a tool to roughly engineer a liberal judiciary, such proposals won’t gain legislative traction—unless liberals first generate traction for their underlying cause. In effect, leading with “structural” fixes to the courts puts the cart before the horse.

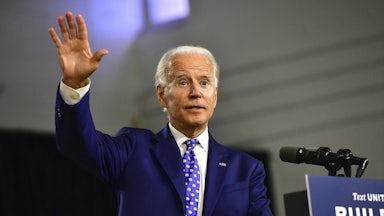

There is a better way forward. History provides an example to follow. Contemporary observers need only look back to the saga of FDR and the Supreme Court—not simply at his notorious failure to expand the court but to his ultimate success in establishing a constitutional regime hospitable to New Deal–scale liberal governance. In particular, they should take note of FDR’s sales strategy, which unabashedly anchored his agenda in both the text of the Constitution as well as the original design of its framers. In forceful but accessible terms, using rhetoric that combined agenda-setting with a sort of civic storytelling, Roosevelt stressed that it was the framers themselves who had crafted the charter for strong governmental economic stewardship—one that both twentieth- and twenty-first-century liberal presidents have built upon, that President Joe Biden is seeking to strengthen, and that a new breed of genuinely reactionary Supreme Court justices are threatening to dismantle.

In 1938, in United States v. Carolene Products, a

Republican-appointed justice and future chief justice, Harlan F. Stone, laid

the cornerstone of the constitutional regime upon which FDR erected the New

Deal: Henceforth, Stone ruled, as long as federal judges could imagine “some rational basis [for a challenged

law] within the knowledge and experience of the legislators,” those judges were to keep their hands off legislation

touching any aspect of the national economy.

Since the mid-twentieth century, however, Carolene Products has become primarily known for an exception to that general rule of judicial restraint. Elaborated in a footnote (known to cognoscenti simply as “Footnote Four”), this exception sanctioned active judicial protection for individual and minority civil rights and liberties. This carve-out became the basis for the judicial interventionism initiated by the Warren court and continued into the twenty-first century

In this way, the Carolene Products template accommodates both of the two dominant contemporary Democrat-leaning factions: culture-war constituencies accustomed to depending on left-tilted judicial activism; and pocket-book, environmental, and other regulatory and safety net–oriented constituencies, accustomed to meeting their needs in legislative and executive agency arenas, untroubled by second-guessing right-wing activist judges. This framework provides a snug constitutional fit for Biden’s popular domestic agenda and may prove to be as attractive to moderate-leaning independents as it is to liberals. It might even pique the interest of some traditional judicial restraint–oriented conservatives in the mold of the late Antonin Scalia, whose doctrinal scaffolding for twentieth-century liberal government is being increasingly savaged by the justices on the court’s right.

Right-wing reactionaries love to say that the Roosevelt court’s constitutional regime, and the “administrative state” it facilitated, flout the original understanding of the Constitution (meaning the unamended 1789 version). For the most part, liberals have failed to notice, let alone spotlight, that this canard gets the facts exactly backward. The new legal right’s real beef is with those venerated “original” framers—George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison.

Naturally, the predominantly rural and frontier society of that time hardly resembles the industrialized, urban economy of today, so it’s no wonder that government was much smaller then than it is now. But the 1789 Constitution that its framers and their immediate successors manifestly laid out and executed was a vision of an “energetic” federal government, empowered to foster a robust and broadly prosperous national economy.

This was etched in constitutional stone by their contemporary Chief Justice John Marshall, in a universally acknowledged 1819 “super-precedent” laid out in McCulloch v. Maryland: “The sword and the purse … and no inconsiderable portion of the industry of the nation are entrusted to [the federal] government,” and “the happiness and prosperity of the nation so vitally depends on the due execution” of its “ample powers.” Indeed, Chief Justice Marshall delineated precisely the same dualistic frame for judicial oversight that the Roosevelt court adopted over a century later—general deference to elected officials, with an exception for active judicial scrutiny wherever, he wrote, “the great principles of liberty are … concerned.”

The chief justice’s rationale for upholding, in that 1819 decision, the legislation creating the second Bank of the United States, was substantially lifted from then–Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton’s 1791 memorandum to President Washington, approved by Washington when he signed into law its predecessor, the first national bank. The law that Marshall upheld three decades later, establishing the second national bank, was supported and signed by President James Madison, who thus recognized not only its policy value but its constitutionality, despite having opposed the first bank in concert with his patron, Thomas Jefferson.

This second Bank of the United States—endowed with enhanced regulatory authority and macroeconomic leverage, akin to its lineal descendant, today’s Federal Reserve—was part of a broader multistatute plan, the “American System.” Championed by Henry Clay and enacted between 1816 and 1828, this program also included tariffs and roads, canals, and other “internal improvements” (that generation’s term for “infrastructure”). According to the U.S. Senate Historical Office, Clay’s plan stands as “one of the most historically significant examples of a government-sponsored program to harmonize and balance the nation’s [economy].” Underscoring the current salience of this founding-era embrace of using federal choreography to align national economic development strategies, New York Times center-right columnist David Brooks recently labeled “the Biden Project” an “updated, monster-sized ... revival ... of Clay’s ‘American System’ ... to secure two great goals: economic dynamism and national unity.”

The “Biden Project,” like Clay’s “American System,” offers real-world benefits, rooted in discernible founding-era credentials. Democratic leaders and their allies could take a page from FDR’s playbook and play up both the practical virtues of Biden’s ideas and their ancient roots. Roosevelt detailed a recipe for the political deployment of “originalist” and “textualist” legal interpretational credos, in the service of a liberal governing tradition, decades before twenty-first-century right-wingers hijacked those shibboleths.

To open the March 9, 1937, fireside chat in which he first broached his court-packing proposal, Roosevelt began, “I hope that you have re-read the Constitution of the United States in these past few weeks. Like the Bible, it ought to be read again and again.” He detailed the Constitution’s grants of federal authority—“all the powers needed to meet each and every problem which then had a national character … to form a more perfect union ... for ourselves and our posterity.”

Unfazed by getting into legal weeds, he shared with his vast radio audience quotes from dissenting opinions by Republican Supreme Court appointees Stone and Charles Evans Hughes, who condemned the court majority for “unwarranted limitation[s] on the commerce clause” and for “reading into the Constitution their own ‘personal economic predilections.’” He concluded by taking the high ground of strict constitutional fidelity, affirming that “I want—as all Americans want—a Supreme Court that will enforce the Constitution as written, [not] amend the Constitution by ... judicial say-so.”

The current drive for court reform will fizzle unless it’s tucked into a similarly canny messaging strategy. Such a campaign should feature actions and measures—such as mandating recusal of justices from cases involving parties who funded their own ascent to the court—that will highlight the new right’s threat to responsive national governance, as the framers designed and which the Biden administration is implementing.

This is, at first blush, perhaps a more meandering way of confronting the right’s capture of the judiciary. But most of the quick fixes bandied about will be inevitably tarred with the brush of rank partisanship. The answer, for Biden and today’s Democrats, is to simply look back to the ideas woven into our civic fabric from the nation’s founding, and the way Roosevelt’s skillful enunciation of those ideas bred consensus around shared goals and allowed him to initiate dynamic, enduring change. Taking a hammer to the McConnell-Trump design may dangle the prospect of a moment of satisfaction; the longer path offers Democrats something more amenable to a greater majority of voters, and something more sustainable down the road.