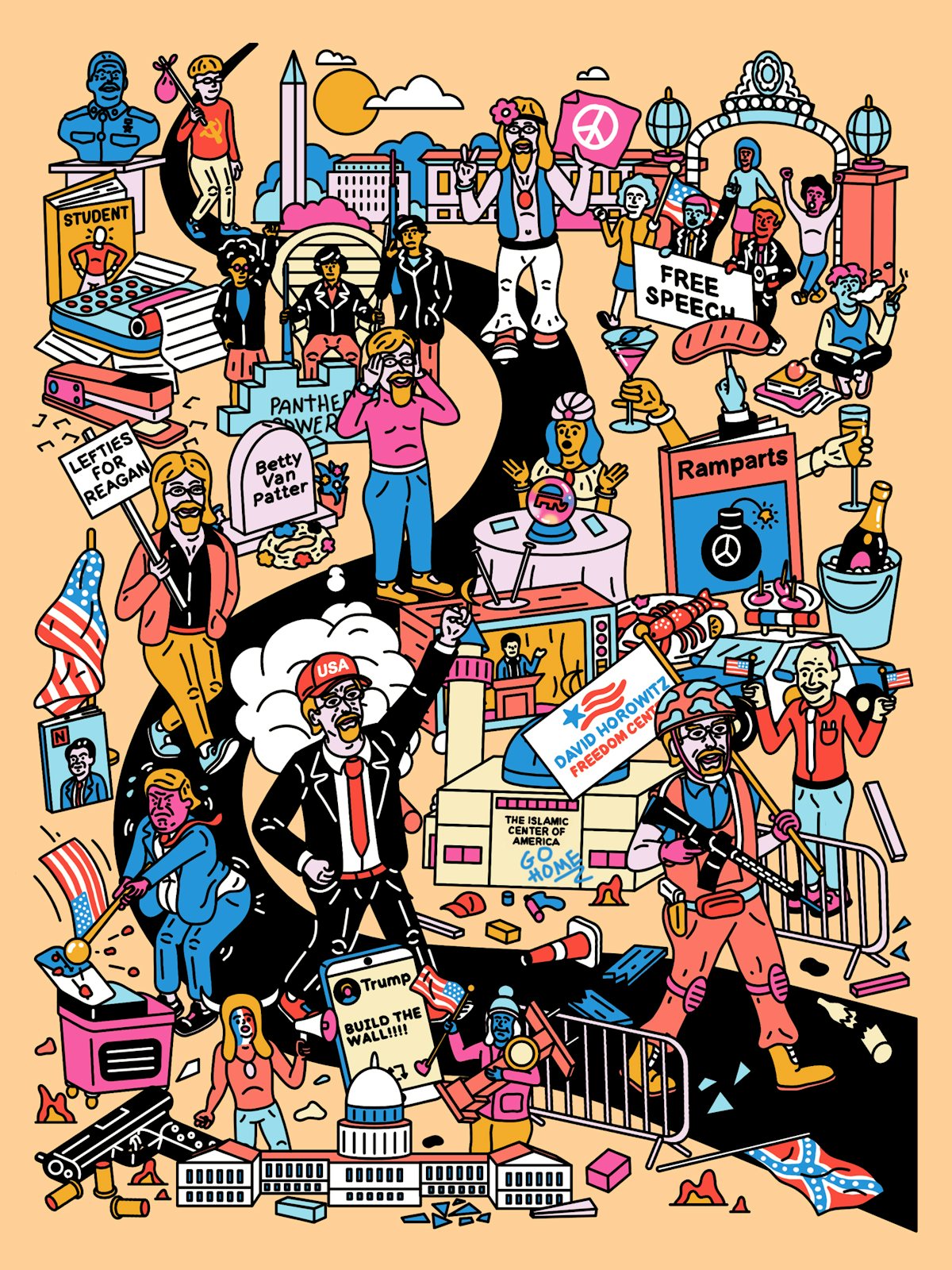

According to our old friend David Horowitz—the radical leftist turned thoughtful conservative turned Trump propagandist whom we’ve been acquainted with, in his various political guises, for more than 60 years—America is on the brink of destruction by way of a communist takeover that only the patriots of the MAGA movement can prevent. That’s the main message in Horowitz’s new book, The Enemy Within: How a Totalitarian Movement Is Destroying America. On the book’s cover are portraits of the seven Democrats allegedly plotting the revolution: Nancy Pelosi, Chuck Schumer, Kamala Harris, Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and Ilhan Omar.

The third book Horowitz has published about Trump since 2017, The Enemy Within is even more of a jihad against liberals and progressives than his previous two (both bestsellers). Horowitz’s justification for writing yet another Trumpist screed is that, in the aftermath of the Democrats stealing the 2020 election, an event he describes (in lip sync with the former president) as “the greatest political crime in the history of the country,” the “totalitarian” threat the party poses is now imminent.

The book begins with a lamentation: “Americans are more divided today than at any time since the Civil War.” The trouble is that almost everything Horowitz has recently written has been calculated to fan the flames of division. Yet he can’t make up his mind whether the tyranny the Democrats are about to install would be more like twentieth-century communism or fascism. He asserts, for example, that the diversity training programs favored by Democrats are akin to the surveillance system of “people’s commissars” created by the Bolsheviks. In practically the same breath, he announces that the Biden administration “has clearly defined itself and its party as a fascist vanguard.”

When the full history of the Trump intellectuals’ betrayal of decent conservatism is written, David Horowitz will have special pride of place, a chapter all to himself. What we offer here is a preview, a chronicle of the twists and turns that led him from radical leftism in the 1960s, when his political journey began, to the far more destructive MAGA movement. Horowitz’s war-fighting rhetoric may sound daring and original to Trump’s followers, but it’s really a reprise of his earlier support for the revolutionary left’s strategy of “bringing the war home” to America’s streets and campuses. His leftist background notwithstanding, Horowitz has achieved the status of a MAGA elder statesman, proudly advancing the causes of some of the movement’s brightest stars, including figures such as Stephen Miller, Steve Bannon, and Jeff Sessions.

We have known David for decades—since graduate school, in Sol’s case, and in Ron’s case, since high school. We were once political comrades, and we admired him for his prodigious intellect. But by spreading the big lie that the election was stolen, our old friend has become a danger to American democracy. That demands our attention.

David Horowitz’s plunge into radicalism happened early. He was born in New York City to parents who were Stalinists and members of the American Communist Party, and, at least to begin with, he followed in their footsteps. In high school, he belonged to a Communist youth group (where he and Ron met). But his political education only began in earnest at Berkeley in 1959, when he arrived from the East Coast as a 20-year-old first-year graduate student in the department of English. Having jettisoned his parents’ creed, he was in search of a new path, free of the ideological rigidity of the old left. It was the dawn of an era of protest, and the Berkeley campus became his radical crucible.

Horowitz was a seeker, with a broad range of political and literary interests. A budding Shakespeare scholar, he also took classes in the Chinese studies department. Along with Sol and Robert Scheer, another Berkeley student, he founded Root and Branch, one of the early, university-based, New Left magazines. For the inaugural issue, published in early 1962, Horowitz contributed a precocious philosophical essay titled “The Question About Meaning,” on the themes of alienation in the works of Marx and Martin Buber. The article reflected David’s fertile, intellectual imagination, and, like the rest of the inaugural issue, it wasn’t very Marxist. (Neither David nor the other editors were particularly interested in the working class as agents of radical change; they were far more focused on students and the underclass.) The magazine was put together with a stapler and a mimeograph machine in the home of one of the editors. In 1963, after three issues, it folded.

Meanwhile, Horowitz had already published his first book, Student. The short volume vividly described the growing unrest on college campuses as students took a leading role in the civil rights and anti-war protest movements. Now 23, Horowitz anticipated the Free Speech Movement, which erupted on the Berkeley campus two years later as students rose up against the university administrators they saw as oppressive. Mario Savio, the movement’s firebrand leader, later revealed that he had read Student in New York City. The book so excited him that he transferred to Berkeley.

Horowitz missed the fireworks of the Free Speech Movement, however, because he and his young family had set off on a five-year sojourn to Sweden and London, during which time he managed to publish two more books that together revealed his intellectual restlessness: a serious, well-argued critique of America’s Cold War policies, The Free World Colossus, and Shakespeare: An Existential View, an unconventional study demonstrating the influence of the controversial existential psychologist R.D. Laing. Now 26, Horowitz was still seeking.

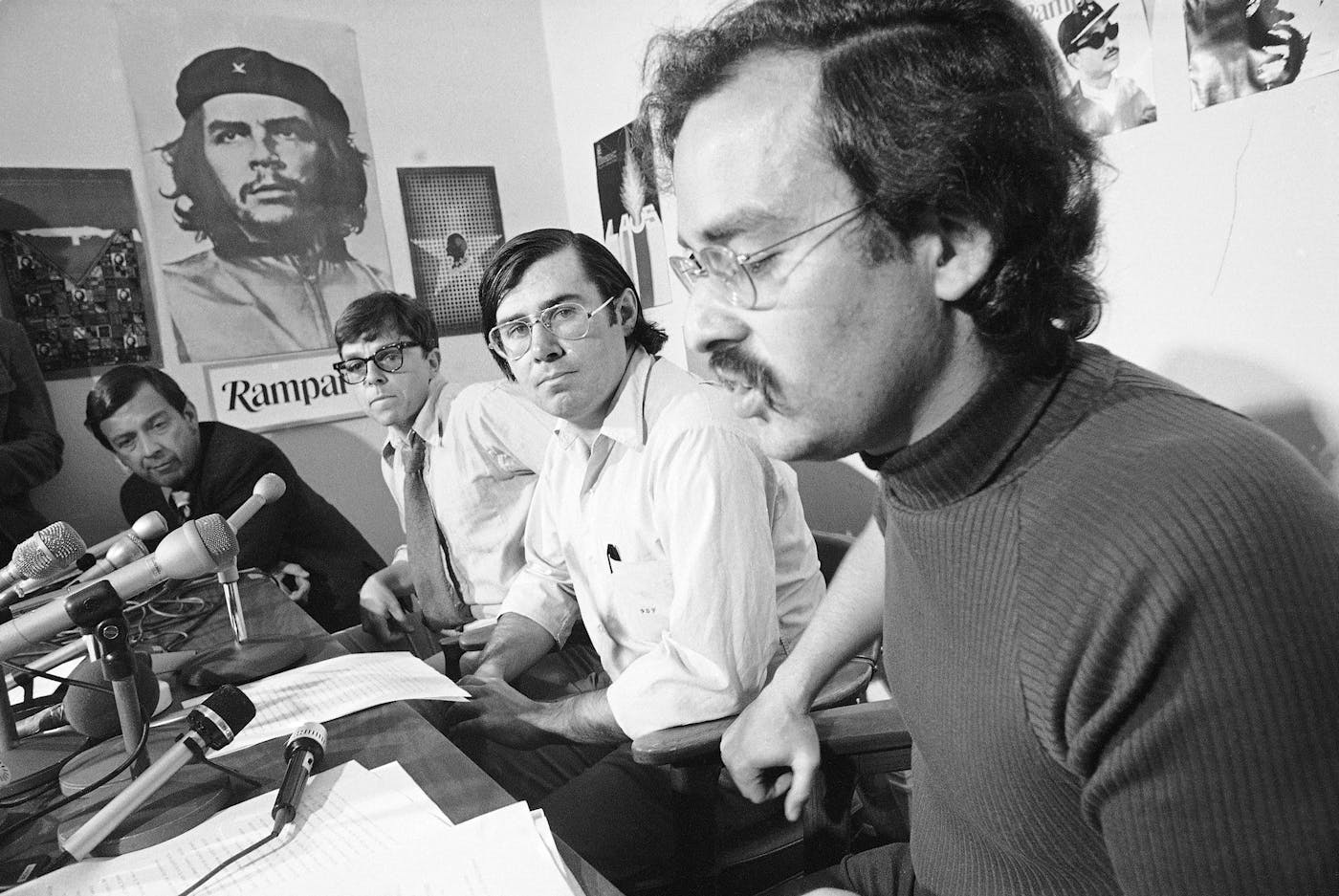

In early 1968, Horowitz moved back to Berkeley after his Root and Branch colleague, Robert Scheer, offered him an editorial and writing position at Ramparts, the slick radical monthly that was then at the height of its notoriety, with a paid circulation that had reached almost 250,000—unheard of for a leftist publication. (Sol, whom Scheer had also recruited, already worked at the magazine.) With the job offer in hand, Horowitz had an epiphany.

The counterculture was in full bloom. The city and the campus, indeed the entire Bay Area, were vibrating with the sounds of resistance and change. San Francisco had just celebrated its “summer of love,” the gun-toting Black Panthers were stirring up Oakland, and raucous street protests were erupting almost every day. It seemed clear that an alternative, radical youth nation had been born in America, and the Bay Area was its capital.

Despite the magazine’s growing readership, it soon foundered, the result of the editors’ own folly rather than any act of government repression. The changing media climate might have sustained a fiscally responsible, mass-circulation New Left publication, but restraint was an alien word in the Ramparts office. There were too many wasteful junkets and three-hour, booze-filled lunches at the priciest restaurants in San Francisco.

In late 1968, the bill collectors came calling. But the miracle of the capitalist system’s Chapter 11 bankruptcy laws insulated the Ramparts editors from the consequences of their recklessness. Nevertheless, the magazine then found itself beset by internal strife, a common occurrence in the radical movements of the time. Robert Scheer briefly took over as chief editor, but was soon ousted in an office coup orchestrated by Horowitz and Peter Collier, another Berkeley graduate student whom Scheer had recruited.

The financially restructured publication moved its headquarters to Berkeley and turned even more radical, as Horowitz and Collier drank the Kool-Aid served up by the left’s most violent elements. They aligned the magazine with protest leader Tom Hayden, then living in a Berkeley commune called the Red Family while awaiting trial on federal conspiracy charges for his role in the riots at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. The young editors enthusiastically published Hayden’s incendiary call for an insurrection led by the Black Panthers, whom he anointed America’s “internal Vietcong.” The lasting image of Ramparts’ second incarnation was a cover depicting a burning bank branch in Southern California. The caption on the cover read, “The students who burned the Bank of America in Santa Barbara may have done more towards saving the environment than all the Teach-ins put together.”

For Horowitz, it wasn’t sufficient to celebrate the Black Panthers in the pages of Ramparts, and he soon grew close with Huey Newton, one of the Panther leaders. He became a frequent visitor to Newton’s lavish penthouse apartment, which sported majestic water views, and proudly raised more than $100,000 for the Panther’s community projects. Newton, in turn, viewed Horowitz as so vital to his operation that he assigned him a Panther body man, a military veteran, to serve as a personal liaison.

Horowitz’s wild, improbable ride with Newton was a fatal attraction—except that it wasn’t the Ramparts editor for whom it turned deadly. Among the services Horowitz performed for the Panther leader was recommending a 44-year-old Ramparts employee named Betty Van Patter for a job with the organization as a bookkeeper. Months after Van Patter, a mother of three children, began working at the Panthers’ office in Oakland, she suddenly disappeared. When Horowitz asked his Panther contacts about her, he was threatened and told to shut up. On January 17, 1975, Betty Van Patter’s body was found floating in San Francisco Bay, her head crushed by a blunt instrument. The police launched a criminal investigation but never solved the murder.

In Horowitz’s 1997 memoir, Radical Son, the chapter about Van Patter is the most disturbing section, reading at once like a detective story and a Dostoyevskian descent into hell. Van Patter was killed, Horowitz argues, because she had learned too much about the Panthers’ shady financial dealings and was suspected of being an informant. The shock of her death made him recognize, finally, that his bromance with Huey Newton was a derangement. In his memoir, he lamented, “I was forced to confront myself in a way I never had to before.... Everything now appeared before me in a pitiless, unrelenting light.”

Two years after Van Patter’s murder, Sol visited Horowitz and found his friend still mourning and in the grip of an existential crisis. In Horowitz’s desperation, he was even seeing a psychic healer. The dream of revolutionary Berkeley was over. He was a seeker again, looking for new meaning to his life. Within a few years, he’d find it: The ex-Berkeley radical was about to experience another epiphany—this time within the erstwhile tolerant, big-tent conservative movement.

In December 1979, Horowitz announced his disenchantment with the left in The Nation, the magazine that had been a pillar of American progressive journalism for over a century. His thoughtful essay posed this essential question: “Can the left take a really hard look at itself—the consequences of its failures, the credibility of its critiques, the viability of its goals? Can it begin to shed the arrogant cloak of self-righteousness that elevates it above its own history and makes it impervious to the lessons of experience?”

Horowitz and his writing partner Peter Collier later wrote a more definitive article about their break with the left for The Washington Post Magazine, “Lefties for Reagan.” Making it clear that they now considered themselves conservatives, the authors also insisted they did “not accept Reagan’s policies chapter and verse.” Nevertheless, they said, “We agree with his vision of the world as a place increasingly inhospitable to democracy and increasingly dangerous for America.”

David Horowitz, in other words, was beginning his rightward turn as a neoconservative, just like the neoconservatives he and his fellow Trumpists now routinely denounce as traitors and renegades. He later assured readers that he was committed to the Burkean vision of “respect for the accumulated wisdom of human traditions” and hadn’t simply “exchanged one ideology for another.”

It was in that ecumenical spirit that Horowitz convened the Second Thoughts conference, which aimed to gather journalists and thinkers reconsidering their former radical political commitments. Held in October 1987 at a hotel ballroom in Washington, D.C., the event was funded by several right-wing foundations, although Horowitz affirmed that it was not meant to “prescribe any political program for our participants to endorse.” The panelists were a diverse group of well-known former leftists and liberals who had provocative and sometimes clashing things to say on current issues. A keynote speaker, Julius Lester, recounted the lessons he had learned during the 1960s, when he was an activist with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. As the war in Vietnam ground on, he came to believe that the anti-war movement had become anti-American. “All too quickly, unrequited idealism can become surly and aggressive,” Lester warned. “Ideology does not permit second thoughts.” Having stood for so many years on the left, he added, he wasn’t about to make the same mistake by branding himself part of the right.

Three years later, Horowitz and Collier convened another Second Thoughts conference, this time focusing on the issue of race. Again, the meeting was intellectually diverse. The tolerant conservatism Horowitz encouraged at the Second Thoughts conferences was reflected in an extraordinary essay he wrote for the January 1993 issue of his new monthly magazine, Heterodoxy:

Conservatism, then, is not an ideology in the sense that liberalism, or the various forms of radicalism are. It is not an “identity politics” whose primary concern is to situate its adherents in the camp of moral humanity and thus to confer on them the stamp of History’s approval. It does not have a party line. It is possible for conservatives to question virtually any position held by other conservatives including, evidently, the notion that they are conservatives at all, without risking excommunication, expulsion, or even a raised eyebrow.

If David Horowitz still believed in those moral guideposts for conservatives, we would likely still be with him. Alas, our old friend couldn’t resist being drawn to the radical party line yet again.

After the Second Thoughts conferences, Horowitz used his entrepreneurial skills to advance several projects within a network of right-wing funders and tax-exempt foundations, eventually launching his own conservative think tank, the wonky-sounding Center for the Study of Popular Culture. Over the years, the center became less wonky, but also less thoughtful and ecumenical. In 2006, in a kind of “dear leader” moment, its name was changed to the David Horowitz Freedom Center, and the spirit of “second thoughts” soon gave way to the militant thoughts of Chairman Horowitz. Heterodoxy was supplanted by the publication FrontPage Magazine, which now carries the slogan “Inside Every Progressive Is a Totalitarian Screaming to Get Out”—itself a rather totalitarian concept. Horowitz makes no bones about what his organization is really after. The center’s website offers this statement of purpose: “The David Horowitz Freedom Center is unique among conservative think tanks whose emphasis is on public policy and institutional reform in that it sees its role as that of a battle tank, geared to fight a war that many still don’t recognize…. The Center remains unique as an organization dedicated to the war and to developing strategies to win it.”

The drift away from heterodoxy toward party-line orthodoxy also became evident at one of Horowitz’s other projects, the Restoration Weekends. The three-day retreats for conservative thinkers and activists are held every year at the opulent Breakers resort in West Palm Beach, not too far from Donald Trump’s lair at Mar-a-Lago. Like the Second Thoughts conferences, the retreats started out intellectually and politically diverse, and the panels included at least some mainstream liberals and centrists. At one of the early events, for instance, Ron shared a platform with the liberal journalist Matt Bai, a politics reporter for The New York Times Magazine, and Marc Cooper, a contributing editor with The Nation. Yet Horowitz soon began appealing to conservatives to stop talking so much and to start beating the drums of political war, setting an example himself by frequently denouncing President Obama as a “communist” and/or a “traitor.”

By the 2016 election, the retreats had turned into cheerleading sessions for Trump’s brand of nationalism and populism. After the election, Steve Bannon was selected as the Horowitz center’s Man of the Year, in part for his role in helping Trump win the presidency. Presenting the award, Horowitz praised Bannon for “the ability to stand firm under fire,” just like Trump. The following year, Bannon was a repeat winner, even though his serial provocations had recently sent him crashing out of the Trump White House. Still, Horowitz cited Bannon for waging “a war for our country.” This time, Bannon received the Annie Taylor Award for Courage, named for the 63-year-old woman who went over Niagara Falls in a barrel in 1901. The award was unintentionally ironic; you might say that Steve Bannon had just gone over Niagara Falls without a barrel.

By now, Horowitz had perfected what could be called the Mike Tyson approach to American politics. In his 2017 book, Big Agenda, he proposed that Republicans take lessons in electoral strategy from the ex-heavyweight champ, who had famously observed that “everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.” In order to win the struggle for America’s future, Horowitz declared, conservatives “must begin every confrontation by punching progressives in the mouth.” Readers of Horowitz’s manifesto had to be struck by how often the “punch in the mouth” meme and similar references to physical combat appear in the text: “the strategy is to go for the jugular;” “it’s time to take the gloves off”; “take no prisoners; stay on the attack.” Not that the new president needed any encouragement from Horowitz—he was already reveling in metaphorically whacking his perceived enemies.

Indeed, among all the 2016 Republican candidates, it was Trump’s willingness to take up the tools of war, to hit Hillary where it hurt, that turned Horowitz into an early supporter of the politically inexperienced, vulgar billionaire. Horowitz believed that principled conservatives who failed to support Trump should also from time to time get the proverbial punch in the mouth. In fact, he personally delivered one such blow during the campaign, calling Bill Kristol a “renegade Jew” in the pages of Steve Bannon’s alt-right publication, Breitbart. According to Horowitz, Kristol betrayed the Jews when he sought a Republican candidate other than Trump, thus giving aid and comfort to that known enemy of Israel, Hillary Clinton.

None of the pilgrims to the Restoration Weekends—who included Charlie Kirk, Chris Ruddy, Sebastian Gorka, Jeff Sessions, Louie Gohmert, Ted Cruz, and Mike Pence—were quite as important for Horowitz’s long-term influence project as the young Stephen Miller, soon to become President Trump’s policy consigliere and main speechwriter. Horowitz had mentored the teenage Miller from his days as a racial provocateur at Santa Monica High School, and then recommended him for a position with Senator Jeff Sessions. After Sessions became the first sitting senator to endorse Trump, Miller moved up to become a rising star on the Trump campaign staff, and eventually the main architect of the Trump administration’s draconian and heartless immigration policies.

In her revealing book about Miller, Hatemonger: Stephen Miller, Donald Trump, and the White Nationalist Agenda, journalist Jean Guerrero traced how Horowitz used Miller to help shape Trump’s speeches. Miller would give Horowitz a heads-up on forthcoming Trump campaign appearances, and in turn Horowitz would offer ideas that the candidate might use. When Miller emailed Horowitz asking how the government had “‘rigged’ the system against poor young blacks and hispanics,” for example, Horowitz answered with a sound bite: “Everything that stifles the aspirations of minorities and the poor and blocks their advancement … Democrats are 100% responsible for.” The inner cities, Horowitz added, “are war zones.” Littered with talk of “carnage,” Trump’s speeches borrowed nearly the same language: “You can go to war zones in countries that we’re fighting and it’s safer than living in some of our inner cities that are run by the Democrats.”

Naturally, Horowitz expected his influence at the White House to continue for four more years. His second Trump book, Blitz: Trump Will Smash the Left and Win, received a presidential endorsement via tweet—“Hot book, great author”—thus guaranteeing that it would become a bestseller.

When Trump lost, Horowitz might have provided some insights into what Trump got wrong (perhaps it had something to do with going AWOL during the country’s greatest health crisis in a century?) so that future conservative candidates might learn lessons from the mistakes. Instead, he abandoned what little intellectual credibility he had left and joined in the biggest and most dangerous lie yet told by President Donald Trump—that the Democrats had stolen a national election in broad daylight.

To help sustain the lie, Horowitz was duty bound to deliver another quickie Trump book within six months of the lost election. Not that The Enemy Within provides evidence that a crime was committed on November 3, 2020. It’s basically a clip job, repeating the wild and disproven fraud allegations made by Rudy Giuliani, Sidney Powell, Peter Navarro, and other Trump fabulists. In the screed, Horowitz claims a vast criminal conspiracy carried out at polling places in many of the 50 states. Yet there’s one little fact missing from the dossier—the name of a single person who participated in the “biggest crime in American history.” We have heard, of course, of “victimless crimes”; for Horowitz and his fellow conspiracy theorists, the alleged election fraud is a history-changing crime that hasn’t a single named perpetrator.

Trump’s best legal minds, including Rudy Giuliani and Sidney Powell (and their mouthpieces in Trump media), did put forth the names of two guilty parties: Hugo Chávez (deceased) and Dominion voting machines. But when Dominion began filing billion-dollar lawsuits, most of the Trump world backtracked or recanted. For Horowitz, the Democratic Party is guilty of terrible crimes that no one can prove, while the MAGA criminals who stormed the Capitol under the glare of hundreds of video cameras are as white as snow and as red, white, and blue as the patriots of 1776. “The protesters inside the Capitol are heroes,” Horowitz tweeted on January 6, as the mob ransacked the Senate and House chambers and threatened to kill his friend, Mike Pence. “They will not be able to stop the steal, but they will expose the lies that are defending the steal. Shame on the Republicans who caved to Biden’s criminals.”

One of the laugh lines in The Enemy Within is the outrage Horowitz directs against what he calls the liberal “tax-exempt advocacy culture,” a category in which he includes the Southern Poverty Law Center, a nonprofit that uses a “successful but sinister” political fundraising strategy. Talk about the pot calling the kettle black. According to the official IRS website, “all section 501(c)(3) organizations are absolutely prohibited from directly or indirectly participating in, or intervening in, any political campaign on behalf of (or in opposition to) any candidate for elective public office.” We aren’t lawyers, but those prohibitions sound as if they would apply to the Horowitz Freedom Center’s relentless support of Trump, as well as its financial support, to the tune of $175,000 (as reported in The Washington Post and The Intercept), of the Party for Freedom of the Dutch ethno-nationalist politician (some would say white supremacist) Geert Wilders, then campaigning for the Netherlands Parliament. (The first of the donations came in March 2014; later that year, Wilders was a speaker at the Restoration Weekend.)

The IRS appears reluctant to provide any serious oversight, so Horowitz manages to raise a significant percentage of the Freedom Center’s yearly $6 million budget through tax-exempt donations from conservative foundations and individual big funders. That budget allows Horowitz to take a salary of over $600,000, according to the center’s latest tax filing. Some portion of the center’s budget is also raised through Horowitz’s signed fundraising letters, which go out to a vast email list. Horowitz typically begins each with a personal salutation, and then issues a dire warning: America is about to be overrun by radical Islamists or Central American immigrants, or educators are turning public schools into centers for leftist indoctrination. Then comes the pitch: Send me $35 or $50 so the Freedom Center can continue fighting to save the country.

One recent Horowitz letter reads: “I’m sure you’ve read and seen countless stories about the Left pushing God out of our schools....After all, this is a tactic from radical communist dictator Vladimir Lenin—he said, ‘Give me four years to teach the children and the seed I have sown will never be uprooted.’” Then Horowitz asks for a small “tax-deductible” donation to protect America’s children from Leninist indoctrination. Lenin did say something like that about education, but here’s the Lenin quote more relevant to Horowitz’s own political advocacy: “We can and must write in a language which sows among the masses hate, revulsion, and scorn toward those who disagree with us.”

In the arc of David Horowitz’s life as a writer and political activist, there is a recurring cycle: an attraction to the most extreme, pugilistic flank of an ideology, a period of reckoning and second thoughts, and then a relentless drive toward the violent fringes of another radical crusade. The stakes seem to increase with every fitful change of heart. With his Freedom Center battle tank, his Restoration Weekends, and his recent bestsellers, Horowitz has become one of the most effective propagandists for a destructive mass movement of millions of middle- and working-class Americans. Such a movement threatens our democracy far more than the campus-based radicalism Horowitz championed during his Berkeley and Ramparts period.

In that earlier era, he celebrated the burning of a bank by a student mob. Today he’s an intellectual pyromaniac who honors the MAGA mob that attacked the U.S. Capitol on January 6. Horowitz’s provocations are calculated to destabilize the electoral process. Perhaps most despicably, he has compared Democrats’ response to the Capitol insurrection with Hitler’s response to the 1933 Reichstag Fire, which the Führer used as an excuse to unleash his horrors on Germany: “The difference was that for Hitler,” Horowitz wrote, “the phantom enemy that justified his depredations was the Jews, while for the fascist Democrats it is ‘white supremacists,’ whose actual numbers are fewer even than the Jews.” But the only political tactic reminiscent of the rise of the Nazis is Horowitz’s (and Trump’s) big lie of a stolen election. It’s the historical equivalent of the Nazi’s claim that the Weimar liberals “stabbed Germany in the back” and lost World War I. Such rhetoric makes Horowitz an enemy of the open society and beyond the pale of rational political discourse.

Our old friend must be defeated on every political front on which he operates, a counteroffensive that should begin by investigating and exposing the Horowitz center’s fundraising scams and the potential abuse of its tax-exempt status. Horowitz will surely protest loudly that the leftist Democrats and traitorous Republicans are canceling his speech. (He already complains of that.) Of course, his free-speech rights should be protected, just as every other American’s are. But you don’t get to ignite warfare and take pride in “fighting fire with fire” and then cry foul when the other side fires back.