Two men dropped their tools and fled on foot from an approaching motorbike. They abandoned their own motorcycle, yellow jugs of water, two hoes, and several charred lumps of wood. Nearby, wisps of smoke leaked from soil mounds. Further afield lay bare roots of freshly felled trees. They had been making charcoal, the same way people have done for years, stretching back into prehistory: Cut down trees; gather the logs and branches into piles; cover them with earth; light a fire underneath; and let it slowly burn for about a week to produce a fuel that burns hotter and discharges less smoke than wood does.

This charcoal produced from the receding forest at Agyana, an agrarian community on the edge of Nigeria’s capital territory Abuja, is then packaged in bags and sold to consumers all over the world for their barbecue grills, many of them unaware of the origin. It’s also in high demand locally, where urban households buy it from kiosks to cook their meals. The producers, mostly young men, invade the forests in droves in search of income. In Agyana, the charcoal producers have formed an association. The two men who fled, association chairman Gimba Abubakar explained, ran from him because they did not pay the association’s levies.

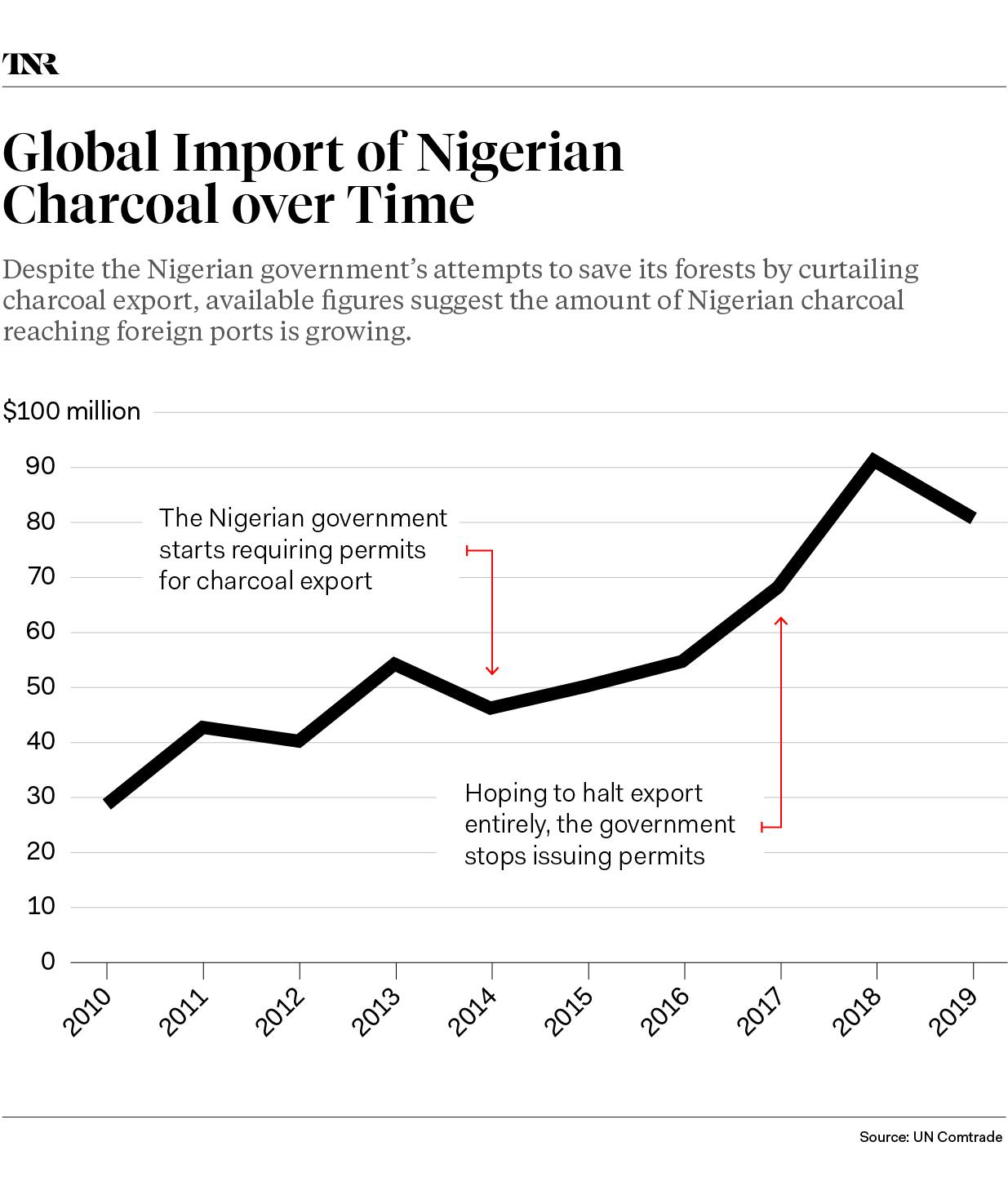

Nigeria lost nearly half of its forest area between 2007 and 2017, according to the World Bank’s Little Green Data Book. In 2017, the staggering deforestation forced environmental policymakers to recommend a de facto ban on charcoal export by ceasing to issue the permits required to produce charcoal for export legally. But the following year, with this policy still in place, other countries’ import of Nigerian charcoal grew by 34 percent, according to Comtrade, the United Nations export and import database. Charcoal use for pleasure, rather than subsistence, seems to be increasing: In 2020, the United States alone imported over 158 million kilograms of charcoal from various countries, 42 percent more than in 2019 and more than twice the amount a decade ago, in 2010.

Africa accounted for about two-thirds of global wood charcoal production in 2018, with dire consequences for the continent’s carbon-absorbing forests. Deforestation is frequently blamed on local dependence on wood fuels, in addition to land cleared for farming, timber, and construction. But there is also another factor: illicit charcoal export to countries in Europe and North America with abundant modern energy sources, consuming charcoal for leisure and novelty. And because illicit charcoal export is hard to track, very little is known about the extent of the issue.

/ In honor of Earth Day, Apocalypse Soon content is free to registered users until April 29. Start reading now.

In 2014, Nigeria started requiring charcoal exporters to obtain a permit from the Federal Department of Forestry by submitting, among other things, a reforestation plan for their area of production. But rampant deforestation continued, hence the 2017 decision to stop issuing permits entirely. The 2017 policy shift doesn’t seem to have had the desired effect either. Nigerian official charcoal export figures don’t match international charcoal import figures: According to U.N. Comtrade, countries around the world reported importing more than $91 million worth of Nigerian charcoal in 2018 alone and more than $80 million in 2019, while the country reported just $4.5 million of charcoal export in 2018 and about half that amount in 2019.

There’s some reason to believe these exports may be reaching American consumers who aren’t aware of the origins. In December 2019, for example, two years after the government stopped issuing permits for the export of charcoal, over 19,000 kg of hardwood charcoal was unloaded at the port in Miami, Florida, according to Panjiva, a subscription-based website with import and export details on commercial shipments worldwide. The port of lading was Algeciras, Spain, but the product originated in Nigeria, shipped in a 40-foot container.

A Nigerian company, Ike Godwins Business Solutions, supplied the charcoal to Florida-based Red Ember Trading, which sells hardwood charcoal to Americans. Red Ember Trading is a subsidiary of Goldengrill, a Spanish charcoal manufacturing company. Goldengrill claims on its website that its product is “made of selected woods which are processed under strict pruning control required by the environmental organizations in the Economic European Community”—a claim hard to square with Nigeria’s export ban and widespread unsustainable practices of charcoal production. Goldengrill did not respond to emails and phone calls requesting comment for this story.

Nigeria’s Ministry of Environment still maintains that charcoal export is banned. “Yes, I confirmed it has been banned,” texted Sagir el Mohammed, the ministry’s director of information. Adekola Razak Kolawole, director of the Federal Department of Forestry, agreed in a phone interview: “We have a total ban on charcoal export.”

The discrepancy between official policy and outcome is tough to untangle, but Kolawole, the director of the Department of Forestry, said the decision about the ban had been clearly communicated to Nigeria’s customs. He doesn’t understand, he said, why charcoal is still being allowed through the country’s ports, given that his department had not issued any export permits since 2018. The Nigeria Customs Service, meanwhile, denies having any responsibility for stopping the exports. Charcoal, spokesman Joseph Attah said, is not currently in the country’s export prohibition list that customs is tasked with enforcing. Officials at the Department of Forestry countered that getting a product into the prohibition list requires legislative action, which takes a long time, and said customs was merely covering for its failure in enforcing the ban. The current export prohibition list has only eight items, including corn and timber.

As Nigeria struggles to control the trade that is destroying its forests, the international community isn’t exactly helping. Countries have no binding treaty to seize Nigerian charcoal even when it is exported illegally. That is not the same with wood species covered under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. “You cannot export rosewood,” said Tiamiyu Oladele, Kolawole’s predecessor at the Forestry Department, adding that without a valid export permit, upon arriving in a country of destination, the product would be impounded. In a troubling loophole, there is no similar regulation that applies when these endangered species are processed and shipped as charcoal.

Traders routinely obscure the origin of Nigerian charcoal. In a market survey of barbecue charcoal in Germany, the environmental nonprofit World Wildlife Fund found that while no charcoal sold in Germany was labeled as being from Nigeria, some of it clearly was from Nigeria, particularly the charcoal Germany imported from Poland, which in 2017 counted Nigeria as its second-highest producer of charcoal, after Ukraine. “When I confronted German customs with the results and ask what they are planning to do, the answer was ‘nothing—when the charcoal from Nigeria arrives, it is legal by definition,’” said Johannes Zahnen, senior adviser for forest policy at WWF. The EU Timber Regulation that came into effect in 2013 prohibits entry of illegally produced tropical woods but does not specify charcoal.

Since 2017, when WWF first conducted the market survey, it has followed up with two more in Germany and similar reports in Switzerland and Belgium. “All results are more or less the same,” Zahnen said. “Forty to 50 percent of the charcoal is from tropical species, many of them from Nigeria.” WWF’s campaign against illicit charcoal in Europe has not led to any policy changes. One Polish company it identified as relabeling Nigerian charcoal with “Made in Europe” did briefly lose its Forest Stewardship Council certificate, which is intended to indicate that a company’s products come from sustainable forests. But the company, Dancoal, was recertified in 2019.

The matter of Nigerian charcoal called into question the reliability of the FSC certification system: Nigerian charcoal by definition should not be FSC-certified, since no Nigerian forest is certified by FSC. In December 2019, FSC acknowledged in a report that it had discovered that some of the charcoal products it certifies were not coming from certified forests and said it would consequently terminate 63 FSC certifications between 2018 and early 2019.

Dania Mousa, media engagement manager at FSC, in an emailed statement, explained that Dancoal’s certificate was reinstated after the company demonstrated that it had addressed all nonconforming FSC products in its supply chain and committed to purchasing charcoal only from FSC and legal sources: “Dancoal was monitored for one year, and FSC continues to monitor the charcoal markets in Europe.”

Polish imports of Nigerian charcoal, however, continue—$11.5 million worth in 2019, according to U.N. Comtrade. Europe is still one of the biggest destinations for illegal charcoal from Nigeria and also serves as a conduit to other continents. Nigerian charcoal is certainly being burned in the U.S., for example, without being labeled as such.

A company called Bluecamp, registered in Georgia, received nearly 18,000 kg of charcoal shipped from Antwerp, Belgium, to Savannah in April 2019, according to the bill of lading obtained from Panjiva. The charcoal was originally supplied by a Nigeria-based company, Primewaters Trading and Logistics, from Lagos. Both companies had similar transactions a year earlier with the bill of lading from Algeciras, Spain. Abayomi Iwajomo, CEO of the company according to his LinkedIn profile and multiple business directories, declined to comment on the transactions.

Similarly, when a 20,000 kg shipment of Nigerian charcoal was received in a port in South Houston, in August 2018, the bill of lading listed the point of origin as Antwerp. The charcoal was supplied by Phoenix Import and Export, a Nigerian freight forwarder, to MBA Multiservice, a Houston-based company. Algeciras, Spain, was the port of lading listed for 20,000 kg of Nigerian charcoal supplied in July 2018 to JNK Investment, a New Jersey–based company, by Leerad West, a Nigerian company.

The fact that tracking charcoal export is this complicated may help explain why charcoal rarely comes up in global climate change conversations, despite the danger the trade poses to tropical forests. Many climate advocates may perceive charcoal as an energy alternative used mostly in Africa by people without electricity. “It’s not broadly known that Africa, in fact, exports charcoal to some other parts of the world,” said Catherine Nabukalu, the project coordinator of District of Columbia Sustainable Energy Utility, who researches the global charcoal supply chain.

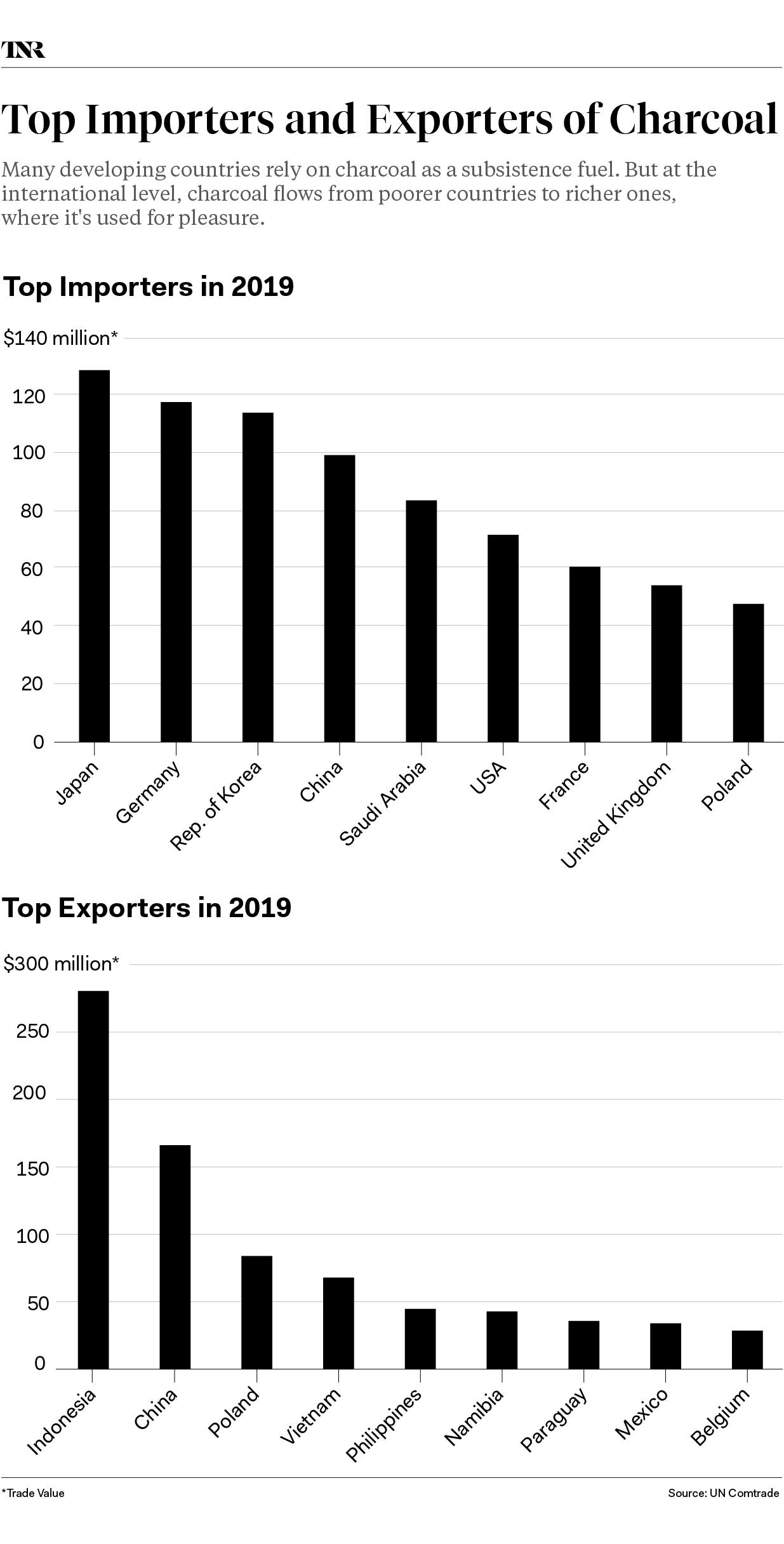

When Nabukalu first questioned climate advocates’ neglect of charcoal in conversations about global carbon emissions, her then professor, Reto Gieré from the Department of Earth and Environmental Science at the University of Pennsylvania, encouraged her to research charcoal as an energy source during her master’s program at the university. Together, they published their findings in 2019 in the journal Resources. “The charcoal trade is highly informal, characterized by low record keeping and little to no tracking of the source of inputs and waste materials along the value chain,” they wrote. While charcoal production occurs predominantly in developing countries—more than 50 percent is produced in Brazil, Nigeria, and Ethiopia, specifically—the top importers are disproportionately high-income countries with dense, reliable energy grids: Germany, Japan, the U.K., the U.S., and France are all in the top 10.

“What bothers me is the export to rich countries,” Gieré said. “I think we should restrict the import because it’s really used basically for leisure. It’s not essential. In the countries that produce it and use it locally, that’s essential there for the survival of the family. It provides jobs, it provides salaries for people. I think that’s a totally different scenario.”

Trees left untouched absorb carbon dioxide. When felled, they release it. And the process of burning the logs to produce charcoal releases carbon as well. It’s not clear how much this is contributing to global greenhouse gas emissions. The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that fuelwood and charcoal may account for 2 to 7 percent of global emissions, with sub-Saharan Africa accounting for one-third of those emissions.

“It signals that the dimensions of emissions and climate change are distinct in much of Africa, different from the standard narratives focused on fossil fuel emissions,” said Adam Branch, a reader in International Politics and the director of the Centre of African Studies at the University of Cambridge. “We need a better understanding of the many ways that climate change is being driven from different parts of the world as well as of the many ways that climate change is manifesting itself for different communities globally.” Instead, the issue is neglected—partly out of prejudice and misconception. “Charcoal tends to go below the radar of most national and international regulation because it is seen as a premodern, traditional fuel, one that is on its way out in a transition to fossil fuels or renewables,” Branch said.

Climate advocates’ reluctance to focus on charcoal may come from a good place—not wanting to focus on what they see as necessary charcoal emissions for fuel in low-income countries. This comes from the perception that charcoal is a sign of energy poverty, with the belief that the poor should not be deprived of their only source of energy because of climate change. High-income countries, after all, are both disproportionately responsible for climate change and better able to pay for the tools necessary for energy transition.

But the reality of charcoal consumption is more complicated, and bound up in the assumption that food tastes better cooked by charcoal than by gas or electricity. Even in Africa, Nabukalu and Gieré found, charcoal is largely consumed by urban households that have access to electricity, though it may not be stable in some places, and charcoal could be cheaper than gas.

The charcoal trade is growing, and high-income countries are playing a huge role in that. The value of global import of charcoal grew by almost 22 percent between 2015 and 2018, according to analysis of U.N. Comtrade. That’s largely due to high-importing countries like Japan, Germany, South Korea, China, Saudi Arabia, the United States, France, and Britain. As demand soars, it is difficult for low-income countries to enforce a ban on charcoal export. In 2012, for example, the U.N. Security Council imposed a ban on charcoal export from Somalia. Years later a U.N. investigation found that illicit charcoal export from the Horn of Africa was estimated at $150 million annually, generating funds for Al Shabaab, a terrorist group.

Nigerian charcoal traders argue that legal domestic consumption, not exports, is the primary driver of deforestation. “Less than 10 percent of it has been exported out of Nigeria,” said Audu Isa, secretary of the Association of Charcoal Exporters of Nigeria. He denied any involvement of the association’s members in charcoal export since the export ban, and said some members have begun to plant trees, as they have realized that the ongoing charcoal production mainly done by artisans is not sustainable. Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari likewise told the U.N. climate summit in 2019 that his administration would mobilize youth to plant 25 million trees “to increase our carbon sink.” But if the charcoal export problem continues, these tree-planting events may not be able to make a dent in the problem.

In January 2020, I visited one of the two Chinese-run

factories by Kwo-Chief Investment Limited that specifically produced charcoal

for export. The site I visited, in Obimo Nsukka in eastern Nigeria, was as

big as six football stadiums. The way it had functioned, I learned, was that locals

would go into the forests, hunting for dwarf red ironwood. They supplied

the logs to the factories, which have tens of brick kilns. After burning the

logs, the lump charcoal was cut into regular shapes and packaged in cartons for

export.

It’s more efficient than the earth-mound kilns used by artisans in Agyana and other parts of the country—more industrialized. And the villagers in this part of the country hadn’t previously been producing commercial charcoal. The new export factories had created large-scale logging where none had previously existed.

In May 2019, the Nigerian environmental agency ordered the facilities to halt operations, on the grounds that they were illegally producing charcoal for export. The following April, the factories reopened and again began burning the logs being supplied by the locals, who in turn are buoyed by new income.

Until countries that import charcoal start restricting import from countries that have banned its export, and until the international community shows interest in establishing proper tracking and enforcement for the global charcoal trade, it will be almost impossible for countries like Nigeria to protect their tropical forests. Fighting charcoal-fueled deforestation will require multiple steps, to be sure: Modern alternative energy sources need to be cheaper than charcoal in low-income countries. But high-income countries also need to reconsider the habit of cooking food over the charred remains of tropical forests merely for pleasure.