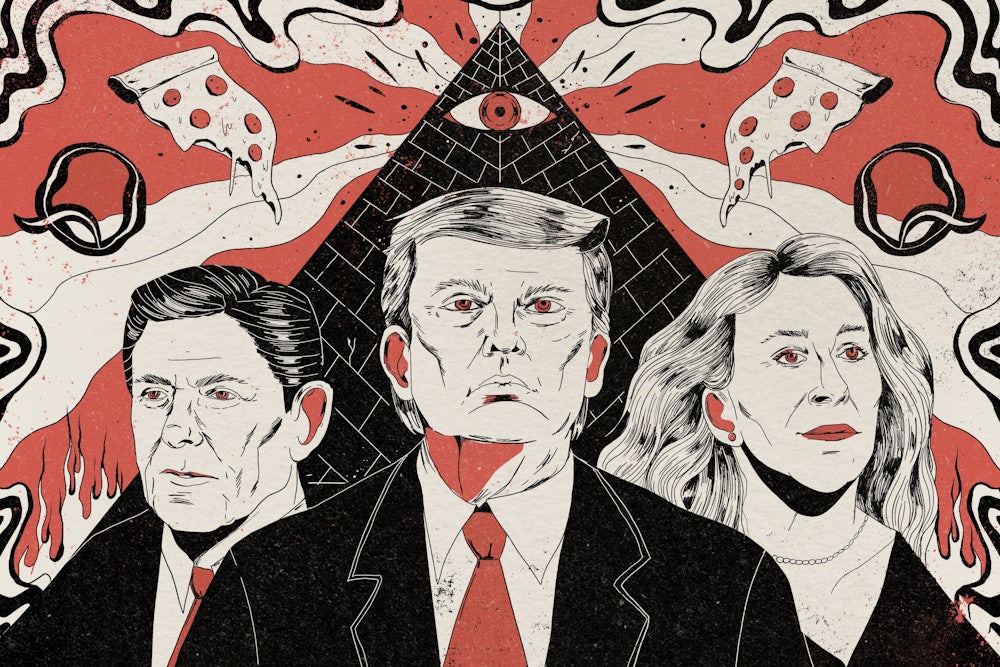

The Republican Party is facing what many observers are describing as a William F. Buckley moment—a make-or-break opportunity to purge the racists and conspiracy theorists who are rapidly gaining control of the GOP.

Marjorie Taylor Greene, the congresswoman who has questioned whether a plane hit the Pentagon on 9/11 and suggested that Democratic political leaders could be executed for “treason,” is more popular among Republicans than Liz Cheney. A full 75 percent of Republican don’t believe that Joe Biden legitimately won the 2020 election, laying the groundwork for Donald Trump to incite an insurrection to steal it for real. The QAnon conspiracy theory—which holds that Democrats in the Deep State undermined Trump’s presidency in order to cover up their child-sex racket, and claims Greene among its more prominent adherents—is favorably viewed by nearly one-third of Republicans, while polling shows that violent anti-democratic sentiment is rampant in the conservative movement.

And when Republican lawmakers had a chance to draw a bright line between their party and the conspiracy theorists and the insurrectionists during Trump’s impeachment trial, the vast majority voted to acquit.

Journalistic commentators have settled into a narrative about what it all means: The American right is reverting to what it looked like before the mid-1960s, when William F. Buckley single-handedly purged the conservative movement of the outright racists and conspiracy theorists, like Robert Welch and his John Birch Society, who threatened to condemn American conservatism to permanent exile on the political fringes. What’s necessary now is for the GOP to show some of Buckley’s backbone, they say. “In the past,” wrote Ronald Brownstein in The Atlantic, “the GOP had a stronger core of resistance to extremism than it’s had in the era of Donald Trump, QAnon, the Proud Boys, and Marjorie Taylor Greene.”

“William F. Buckley got it right the first time,” Jonathan Zimmerman wrote in USA Today, adding, “The only question is whether Republican leaders will have the courage to stand up and say so.”

Such confident appeals to past GOP precedent could not be more misleading. They fly directly in the face of the facts—discovered by a new generation of historians who have dismantled the claim that the GOP and the conservative movement ever split with their addled, racist fringe.

Start with Buckley. The man who founded National Review in 1955 at the tender age of 29 was nothing else if not a politician. The political project that defined him was moving America’s ideological center of gravity to the right. His strategy for doing so was Janus-faced. On the one side, he charmed mainstream cultural gatekeepers, skiing with John Kenneth Galbraith in Gstaad and hobnobbing with Hubert Humphrey at the New York Catholic Archdiocese’s annual Al Smith Dinner. On the other, he plied the far-right side of the fence.

Consider, for example, the direct influence on Buckley’s first book, God and Man at Yale: The Superstitions of “Academic Freedom” (1951), of the ideas of American fascist sympathizer Merwin K. Hart. Buckley later cited Hart as the sort of figure whose tone his new magazine would specifically avoid so as to evade the “fascist” label—even as Hart’s key argument that democracy itself was a foreign, anti-American imposition would continue to exert an obvious influence on many of National Review’s most important writers, like Willmoore Kendall, as the historian Joseph M. Fronczak has demonstrated.

Consider also the work of historian Jesse Curtis, who has showed that the magazine described the decolonization of Africa in terms not very different from that of the magazine of the white supremacist Citizens’ Councils movement. No surprise: Buckley’s own statements on the subject—that Africans were “semi-savages” who would be ready for self-government “when they stopped eating each other”—were far more vicious than anything that Robert Welch ever said.

Although it wouldn’t be fair to beat up only on Buckley. It was Ronald Reagan, after all, remembered today as the avatar of the Republicans’ lost respectability, who in 1971 described African United Nations delegates to a chortling Richard Nixon as “monkeys … uncomfortable wearing shoes.” He espoused conspiracy theories like the claim that Gerald Ford staged assassination attempts against himself to win sympathy votes in the 1976 presidential primaries, and that the Soviet Union had removed 20 million young people to the countryside to practice for reconstructing their society after launching an offensive nuclear war. The newsletter of Reagan’s political action committee advocated the quack cancer cure (and pet Bircher cause) laetrile, which “[m]ay be efficacious against cancer but which government in its wisdom wants to keep people from using.” (The reason was that it didn’t work, and frequently killed people.)

Then Reagan became president—and the only thing that changed was the people around him worked harder to keep his wackiness from the public.

They were frequently frustrated—for instance when Reagan claimed the nuclear freeze movement that drew a million protesters to Central Park in 1982 had been engineered in the Kremlin, or the time he told reporters that apartheid South Africa had “eliminated the segregation that we once had in our own country.” There was also the moment when he quoted to a group of college students visiting the White House Vladimir Ilyich Lenin’s “eloquent statement” of his plan to conquer America: that he would first take Eastern Europe, then “organize the hordes of Asia,” then “move into Latin America”; then “we will not have to take the last bastion of capitalism, the United States. It will fall into our outstretched hand like overripe fruit.”

Except that Lenin never said it. But Robert Welch claimed he did, in The Blue Book of the John Birch Society, the ur-text of his movement.

Such evidence of Welch’s influence on Reagan tells a truer story of how the modern right evolved. Its founding act wasn’t purging the extremist conspiracists like Welch. Instead, the far right better represented the “mainstream” right’s vanguard, according to the organizing metaphor of a forthcoming book from John S. Huntington. Or it was, to borrow the title of a groundbreaking Princeton dissertation by David Austin Walsh, but one component of the “Right-Wing Popular Front.”

To take one crucial example, it is generally agreed that the transformation of Sun Belt states like Texas into Republican bastions was a key driver of the ideological shifts that led to the presidential election first of Richard Nixon in 1968, then of Reagan in 1980. And in Texas, according to a forthcoming study by historian Jeff Roche, it was Birchers as much as establishment Republicans who drove that shift.

Roche’s book is called The Conservative Frontier: Texas and the Origins of the New Right. That term, “New Right,” refers to the key addition to the conservative coalition that made Ronald Reagan president, whose signature innovation was aggressively prospecting for new social issues, enraging ordinary citizens on the ground, and turning them into vectors for recruiting the otherwise apathetic into electoral politics. That was a method the John Birch Society mastered before the New Right even earned the name.

In Orange County, California, for example, parents were livid about sex education in the schools. Before the issue became part of any politician’s platform, the John Birch Society fanned the flames in 1969 with a front group called the Movement to Restore Decency, or MOTOREDE, whose activists argued that the sex-ed advocates of the Sexual Information and Education Council of the United States, or SIECUS, were in cahoots with the Communist-infiltrated National Council of Churches to “destroy the moral character of a generation,” in order to soften them up for the Red takeover. MOTOREDE then produced another extraordinary political innovation, which has remained with us ever since: A Birch activist named John F. McManus announced, “MOTOREDE believes that abortion is murder.” The society soon began organizing around the issue with a film called License to Kill, alongside fundamentalist radio preacher Billy James Hargis.

It was years before Roe v. Wade but smack in the middle of a wave of abortion-law liberalization in state after state. It was the John Birch Society that first discovered the power of the nascent Christian right’s most galvanizing issue. And because the John Birch Society was a secular organization with members of all faiths, it pioneered the sort of operational unity between evangelical Protestants and Catholics that the Moral Majority received credit for when it came along, nine years after the Supreme Court’s landmark abortion rights decision in Roe—a group that Ronald Reagan hugged tight as an ally, even as Birchers were officially personae non gratae.

The John Birch Society leaders’ motivations for joining this fight, as always, were fantastical. They believed abortion was part and parcel of the strategy of the “Insiders”—the shadowy globalists who directed the Communist conspiracy—to weaken America by shrinking its population. It was “people control,” just like “gun control.” That is how front groups work: Find an inviting come-on with the power to arouse an angry citizenry, even if it is just to win their vote; and if this becomes the gateway drug to sell the whole crazy conspiratorial package, all the better.

Another example: the ubiquitous Birch-issued bumper stickers to “SUPPORT YOUR LOCAL POLICE.” If you sported one to signify your horror at leftists who, then as now, criticized urban police forces as racist armies of occupation, fine. Maybe it will serve, to employ a contemporary anachronism, as your red pill, leading you to the twilight struggle against Insiders’ infernal conspiracy to make American police forces bought-and-paid-for adjuncts of the United Nations. QAnon functions much the same way when it sets up tables in town squares around the country urging none-the-wiser citizens to fight the scourge of global sex trafficking.

Other examples proliferate. Those in the know fought the Equal Rights Amendment, historian Erin Kempker demonstrates in her book Big Sister: Feminism, Conservatism, and Conspiracy in the Heartland, because they believed it a cat’s paw for one-world government. Meanwhile, the movement’s brilliant public-facing spokeswoman, Phyllis Schlafly, went on The Phil Donahue Show to explain the alleged harms ERA would do to women’s access to their husbands’ financial support—and “respectable” Republican politicians echoed that line.

Simultaneously, in the late 1970s, television preachers like Jerry Falwell taught their flocks that since “homosexuals couldn’t reproduce,” they set in motion a massive conspiracy to recruit children (in order to ritually murder them, according to another prominent televangelist, James Robison, whose right-hand man was a young Mike Huckabee). From the other side of his mouth, Falwell would take to big-city newspaper op-ed pages to explain decorously, in the language of good-old-fashioned American pluralism, that all his flock were interested in was practicing their faith without government interference, just like everyone else.

This habit of speaking to two audiences at once was mirrored at the level of Republican presidential politics. Ronald Reagan appeared beside Falwell at a rally of preachers at the height of his 1980 presidential campaign to proclaim, “I know that you can’t endorse me … I want you to know that I endorse you and what you’re doing.” Reagan’s endorsement occurred even as, backstage, a leading Christian Reconstructionist—an extremist movement that sought to make the Old Testament the foundation of American criminal law and considered the public school system a conspiracy to spread paganism as the national religion—complained that their guru, Dr. R.J. Rushdoony, had not been included in the event’s program. A Reagan campaign official reassured him: “If it weren’t for his books, none of us would be here.”

Such was the complex dance that has always been at the heart of Republican politics in the conservative era. The extremist vanguard shops fantastical horror stories about liberal elites in the hopes that one might break into the mainstream, such as the “Clinton Chronicles” VHS tape distributed by Jerry Falwell in the early 1990s. The stories included the Clintons covering up the murder of Vince Foster, murdering witnesses to their drug smuggling operation, and participating in a crooked land deal at a development called “Whitewater.” (The New York Times bit hard on the latter claim, setting in motion a chain of events that led to President Clinton’s impeachment over lying in a deposition about a sexual affair.)

Later, an incumbent Republican president ran for reelection on a platform of wartime national unity and policies to spread the beneficence of American capitalism more broadly—while at the same time his backroom operatives got divisive anti–gay marriage initiatives in swing states to flush scared reactionaries to the polls, and the Republican National Committee distributed fliers in rural areas accusing Democrats of a literal conspiracy to outlaw the Bible.

This is why Trumpism is not a reversion to an older, more gothic form of conservatism but an apotheosis decades in the making. Trump may have been our country’s first post-truth president. But the post-truth environment of conspiracy we are living in today has been a long time coming. We owe it in part to the truth-optional habits on the right that Robert Welch and the Birch Society exemplified—and in part to the same Republican elites who were complicit every step of the way.