“Is it possible to be a black lesbian writer and live to tell about it?” asked budding writer and scholar Barbara Smith at the 1976 convention of the Modern Language Association. Among those in attendance was Audre Lorde, an established poet, whose first collection, The First Cities, was published in 1968. The question, largely rhetorical, was addressed to the entire assembly, but Lorde took it personally. “I thought, ‘Oh boy, I’ve got to start writing some of that stuff down. She needs to know that, yes, it is possible.’”

A self-described Black lesbian mother warrior poet, Audre Lorde lived a life of possibility. To her readers, colleagues, and admirers, she offered a radical and liberating vision of the world in her work. Eminently faithful to the tenet that the personal is political, she wrote fearlessly from the landscape of her most intimate self. Lorde treated her body—the range of her corporeal needs, fears, and desires—as a resource of political and creative information, a platform from which she communicated her worldview. She was unique in her determination to speak and write without shame, but at the same time wholly representative, embodying the complexities of a contemporary radical Black feminist identity. Her life emblematized the concept of intersectionality, a term coined in 1989 by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw to describe the ways in which distinct social identities, such as race and gender, are mutually constitutive. Lorde devoted her career to building bridges across social divides as well as nurturing the distinct voices of Black feminist writers who responded to the raw physicality of her imagery and her now famous rallying cries, such as, “Your silence will not protect you.”

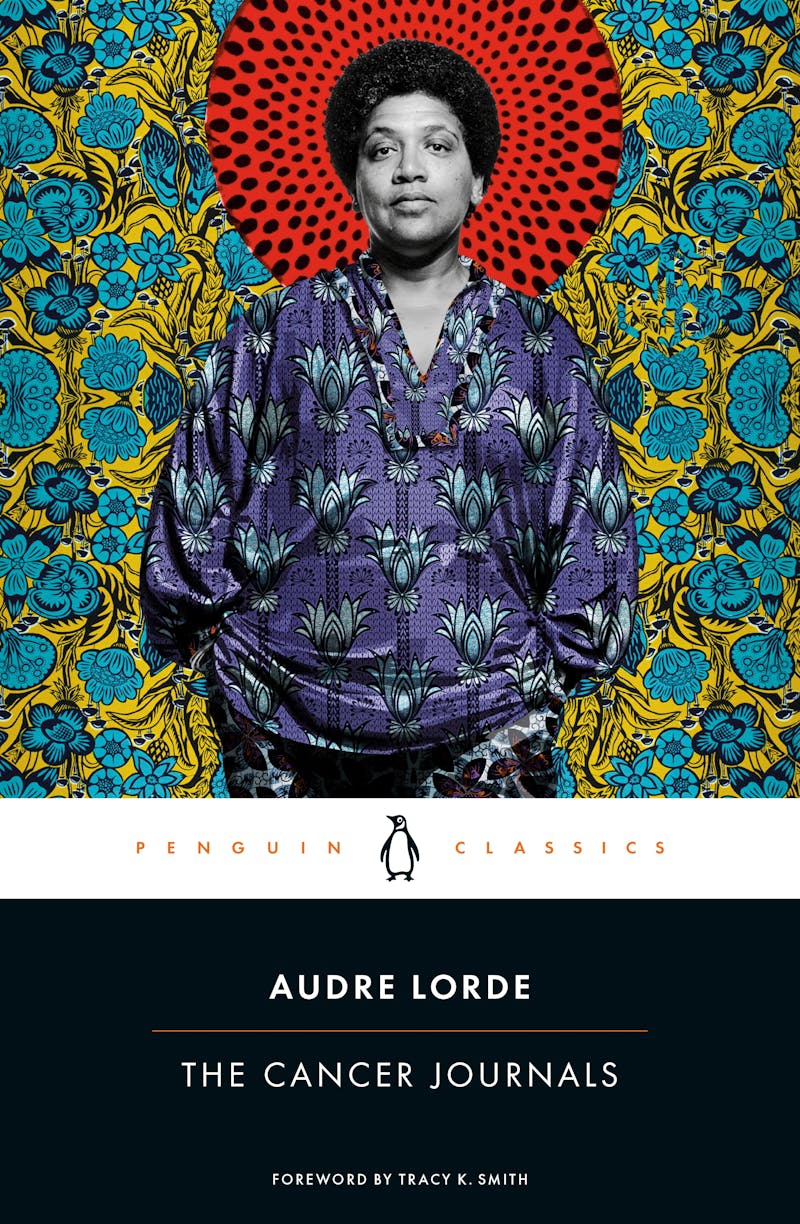

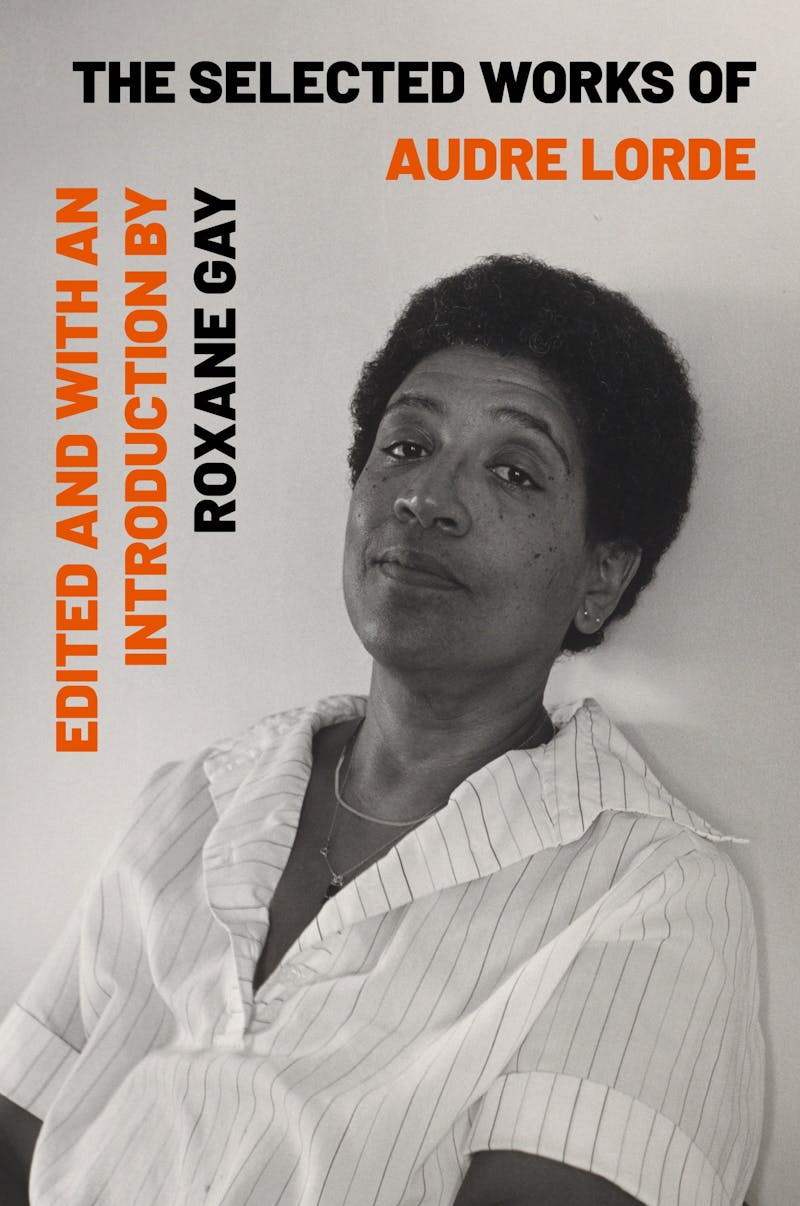

Two recent publications, The Selected Works of Audre Lorde, edited and with an introduction by Roxane Gay, and a new edition of The Cancer Journals, with a foreword by Tracy K. Smith, capture the complexity of Lorde’s singular perspective. The Selected offers the closest thing to a complete portrait of Lorde, putting both her poetry and prose within the same covers, while The Cancer Journals shows a writer in a full-throttled battle with not just the disease but with the larger threat of permanent silence. Together, the books reveal Lorde at the height of her intellectual powers, but also as a human being who, just like the rest of us, faced down fears and uncertainties. The closer she got to death, the clearer became her mission—to approach the world with a kind of ferocious openness, and to insist that she be received with the same.

Born in New York City in 1934, Audre Lorde was the daughter of strict Grenadian parents. They “spoke all through my childhood with one unfragmentable and unappealable voice,” she remembered. Under their forbidding gaze, however, she developed a poetic sensibility. “Poetry was something I learned from my mother’s strangenesses and from my father’s silences,” she remembered in a 1980 interview for The American Poetry Review. Her mother’s influence was the strongest. Lorde told Adrienne Rich: “My mother had a strange way with words; if one didn’t serve her or wasn’t strong enough, she’d just make up another word, and then that word would enter our family language forever, and woe betide any of us who forgot it.” Young Audre thrived underneath and in spite of her mother’s accusative, watchful eye. “In my mother’s house, there was no room in which to make errors, no room to be wrong,” Lorde remembered in her 1982 book Zami: A New Spelling of My Name.

A hybrid of autobiography, mythography, and fiction, Zami is a sensory revelation, an erotic meditation, and a portrait of the artist as a “fat, Black, nearly blind, and ambidextrous” girl growing up in pre-Stonewall New York. In this book and separately in her 1977 essay “My Mother’s Mortar,” Lorde wrote of how her mother dominated her burgeoning sense of her sexual identity:

As I continued to pound the spice, a vital connection seemed to establish itself between the muscles of my fingers curved tightly around the smooth pestle in its insistent downward motion, and the molten core of my body whose source emanated from a new ripe fullness just beneath the pit of my stomach. That invisible thread, taut and sensitive as a clitoris exposed, stretched through my curled fingers up my rounded brown arm into the moist reality of my armpits, whose warm sharp odor with a strange new overlay mixed with the ripe garlic smells from the mortar and the general sweat-heavy aromas of high summer.

The erotic and the literary were inherently intertwined in Lorde’s life. As she explained to Charles Henry Rowell, editor of Callaloo, two years before her death: “My sexuality is part and parcel of who I am, and my poetry comes from the intersection of me and my worlds.”

Lorde never saw herself as a writer of prose. Most of her signature works of prose were born in public forums as speeches, their intensity amplified by her immense charisma and commanding rhetorical presence. Her editor, Nancy Bereano of Crossing Press, had to convince her to transform them into essays. “I am a poet to my bones and sinews,” she once told Rowell. As the founding poetry editor of Chrysalis, a new feminist quarterly, she published the luminary poets of second-wave feminism, such as Patricia Spears Jones, June Jordan, Honor Moore, Pat Parker, and Adrienne Rich, and contributed her own essay “Poetry Is Not a Luxury” to one of the journal’s early issues in 1977. The essay describes the writing of poetry as an act of creation on the highest level. “Poetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought,” she wrote. “The farthest horizons of our hopes and fears are cobbled by our poems, carved from the rock experiences of our daily lives.” Poetry was essential—and essentially maternal and Black: “The white fathers told us: I think, therefore I am. The Black mother within each of us—the poet—whispers in our dreams: I feel, therefore I can be free.”

Lorde’s freedom was intimately connected with sexuality. In 1978, she delivered her paper “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power” at a conference on the history of women at Mount Holyoke College. The conference attracted protests due to its lack of attention to lesbian history. Although “Uses of the Erotic” did not focus on lesbian identity directly, it presented a retort to the distortion and oppression of the full range of women’s sexual experience and expression. The erotic, Lorde argued, was something much deeper and broader than sex, particularly when it came to lesbian consciousness. She found the erotic in the most mundane and profound experiences, from “dancing, building a bookcase, writing a poem, examining an idea,” to grinding spices with her mother’s mortar and pestle. She felt its absence while lying cold and alone in a sterile hospital room, an environment she described as “erotically blank.” Recuperating at home from a surgery, Lorde knew she was on her way back to life when she found herself able to masturbate again.

Both papers derived from “the one thread I feel coming through over and over in my life,” which was “the battle to preserve my perceptions, the battle to win through and to keep them—pleasant or unpleasant, painful or whatever.” To name her experience, to refuse the definitions imposed by others, was Lorde’s primary objective and the touchstone of her creative alchemy. The final stanza of “To the Poet Who Happens to Be Black and the Black Poet Who Happens to Be a Woman” reads:

I cannot recall the words of my first poem

but I remember a promise

I made my pen

never to leave it

lying

in somebody else’s blood.

A Black feminist to her core, Lorde was a vigilant critic of the racism that permeated the women’s movement. She delivered her most searing public indictment at the Second Sex Conference in New York in 1979. Her paper, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” denounces the hypocrisies of white feminists, while condemning the alarming absence of papers addressing race, class, and sexuality at the conference.

It is a particular academic arrogance to assume any discussion of feminist theory without examining our many differences, and without a significant input from poor women, Black and Third World women, and lesbians. And yet, I stand here as a Black lesbian feminist, having been invited to comment within the only panel at this conference where the input of Black feminists and lesbians is represented. What this says about the vision of this conference is sad, in a country where racism, sexism, and homophobia are inseparable. To read this program is to assume that lesbian and Black women have nothing to say about existentialism, the erotic, women’s culture and silence, developing feminist theory, or heterosexuality and power.

Lorde forced the other panelists and conference attendees to face up to the distance between the lives they lived and the theories they espoused. “How do you deal with the fact that the women who clean your houses and tend your children while you attend conferences on feminist theory are, for the most part, poor women and women of Color?” she asked the audience. White women were just as complicit in oppression as the “masters”—the representatives of white patriarchy—whom they characterized as threats to their own freedom. Many of the white women present were chastened and horrified.

Lorde was disappointed that the Roman Catholic philosopher Mary Daly was not there to hear her presentation. She had written Daly a letter to take her to task for her misrepresentation of Black women in her landmark work on radical feminism, Gyn/Ecology. Daly responded months later, and suggested that they meet, an encounter that Lorde biographer Alexis De Veaux describes as “comparatively trivial.” Lorde found Daly’s reserved personality disquieting and was frustrated by her inability to get through to her. Not surprisingly, she turned to the page; the same year, she composed “An Open Letter to Mary Daly,” a reiteration of many of the points she had made in their private correspondence about the racism she believed to be embedded in Daly’s book. The letter was not only a critique of Daly, but also a wake-up call to all white feminists who were unwilling to confront their own biases. Still, as frustrating as she found white feminists—and at one point she swore off speaking to them about racism altogether—she believed in the necessity of a true multiracial feminist collective, and in doing the hard work required to build real and lasting connections across difference.

In fact, Lorde found difference vitalizing. We should neither ignore differences between racial groups nor deny differences within a particular racial group, Lorde insisted. Race was as elastic and complex as gender and sexuality. Lorde eschewed what she called an “easy blackness”—assumed and unexamined. She was hurt when she felt the disapproval of Black people who objected to her sexual identity. Her poem “Between Ourselves” begins:

Once when I walked into a room

my eyes would seek out the one or two black faces

for contact or reassurance or a sign

I was not alone

now walking into rooms full of black faces

that would destroy me for any difference

where shall my eyes look?

Once it was easy to know

who were my people.

“I have a right to be black,” she wrote in her journal at around the same time that she composed the poem. “I have a right to be different and I have a right to survive.”

The year after her encounter with Barbara Smith, Audre Lorde had another momentous experience at an MLA convention, only this time it was her words that rocked the audience. “Beyond coming out,” writes De Veaux, “it was her most revelatory statement to date.” She delivered her statement as part of a panel entitled “The Transformation of Silence Into Language and Action.”

For the panel, Lorde had originally planned to deliver a paper on the theme of lesbian invisibility in contemporary literature, but Adrienne Rich convinced her instead to use the session to describe her experience of a recent cancer scare. At the time, no one was talking so openly about the personal and political dimensions of cancer. Susan Sontag’s groundbreaking 1978 work, Illness as Metaphor, was relatively impersonal; Lorde’s unapologetically confessional account drew on raw emotion. In her MLA address, Lorde described the agonizing three-week period while she waited for biopsy results as completely disorienting. “But within those three weeks,” she wrote, “I was forced to look upon myself and my living with a harsh and urgent clarity that has left me still shaken but much stronger.” She learned a lesson that she shared with the audience: “I was going to die, if not sooner then later, whether or not I had ever spoken myself. My silences had not protected me. Your silence will not protect you.”

A pathology common to all women regardless of race was silence. “The fact that we are here and that I speak these words is an attempt to break that silence and bridge some of those differences between us, for it is not difference which immobilizes us, but silence,” Lorde said. Having faced the specter of final silence—her own mortality—Lorde exhorted the white women in the audience to interrogate their silences on racism. She challenged: “Perhaps for some of you here today, I am the face of one of your fears. Because I am woman, because I am Black, because I am lesbian, because I am myself—a Black woman warrior poet doing my work—come to ask you, are you doing yours?” As Tracy K. Smith notes in her foreword to The Cancer Journals, “It is immensely valuable to witness Lorde, even in the throes of illness, modeling anger as a dynamic process, a source of growth and change.” Lorde believed in the utility of anger, especially in response to racism. “Every woman has a well-stocked arsenal of anger potentially useful against those oppressions, personal and institutional, which brought that anger into being,” she wrote.

The biopsy that gave rise to “Transformation” was, thankfully, negative, but a dread of cancer dogged Lorde from that point on. She felt doomed and powerless. She’d had a potent influence on contemporary feminist thinking and politics, but she could not order her own fate. She did not hide her fear, admitting to those in attendance, “you can hear it in my voice.” That phrase, left out in the essay version of her speech, underscores the most dazzling element of Lorde’s skills as an orator and a writer: her ability to reveal herself entirely to her audience. Both on the page and in person, she spoke from the body.

Lorde would face cancer three times: breast cancer in 1978; liver cancer in 1984; and ovarian cancer in 1987. She knew that speaking out about her own experiences with cancer had the potential to liberate other women to talk about the effects of the disease on their own lives. In 1979, she decided to publish a compilation of journal entries she had recorded before and after her mastectomy. She wrote in her introduction:

Living a self-conscious life, under the pressure of time, I work with the consciousness of death at my shoulder, not constantly, but often enough to leave a mark upon all of my life’s decisions and actions. And it does not matter whether this death comes next week or thirty years from now; this consciousness gives my life another breadth. It helps shape the words I speak, the ways I love, my politic of action, the strength of my vision and purpose, the depth of my appreciation of living.

Her willingness to be vulnerable was a fundamental part of her personality as well as her politics. For Black women, she once said, “that visibility which makes us most vulnerable is that which also is the source of our greatest strength.” Lorde wanted to lead from her strength as a Black woman but also through the example of how she managed her weakness, fear, and pain. It wasn’t an easy balance to achieve, and she struggled as she composed The Cancer Journals with her competing needs to appear strong as well as authentic. The struggle is evident in The Cancer Journals, when she envisions the bravery of Amazon warriors at the same time that she begs for extra blankets from unsympathetic nurses. She confesses to being “shit-scared” in her meditation on the emotional and psychological impact of her mastectomy. “The pain of separation from my breast was at least as sharp as the pain of separating from my mother,” she wrote. The book is saturated with characteristic Lorde-ian wisdom. “The acceptance of death as a fact, rather than the desire to die, can empower my energies with a forcefulness and vigor not always possible when one eye is out unconsciously for eternity,” she wrote.

Lorde used her individual experiences with cancer as platforms to discuss larger cultural problems. A nurse’s comment that, without a prosthetic, her appearance would be “bad for the morale of the office” anchors an essay about the pressure imposed upon women suffering from cancer and its political implications. “Suggesting prosthesis as a solution to employment discrimination,” she writes in “Breast Cancer: Power vs. Prosthesis,” “is like saying that the way to fight race prejudice is for Black people to pretend to be white.” In the essay, Lorde unearths the connections between two experiences—racism and breast cancer—that on the surface appear to be entirely distinct. Her objection to prosthetics was a rejection of another kind of silence and erasure and a defiant refusal to conform to the expectations of others when it came to the way she chose to move in the world.

In 1984, Lorde’s doctors had predicted she would live for only two or three more years. In 1991, she said in an NPR interview that she was grateful to be alive to share her experiences with other men and women. “I left grateful,” the interviewer told her audience, “to have spent time with a woman who showed me that it’s possible to surrender to the reality of tragic life circumstances without giving in.” That year Lorde was named New York State Poet Laureate, the first African American and first woman to be so designated.

Lorde wrote “Today Is Not the Day,” one of her last poems, in April 1992. The poem begins:

I can’t just sit here

staring death in her face

blinking and asking for a new name

by which to greet her

I am not afraid to say

unembellished

I am dying

but I do not want to do it

looking the other way.

Seven months later, Lorde’s 14-year battle with cancer ended. She was 58 years old. At her memorial service, Barbara Smith recalled their first encounter at the 1976 MLA conference. For Smith, Lorde’s presentation had been a milestone on the road to a full Black lesbian feminist cultural and political awakening; she and Lorde had begun a lifelong collaboration, going on to establish Kitchen Table in 1980, the first press to focus exclusively on the work of women of color. Smith’s words were published in a New York Amsterdam News article about the memorial:

“Is it possible to be a Black lesbian writer and live to tell about it?” Audre Lorde answered the question with an emphatic “Yes,” Smith said. Even though she faced ostracism for having the integrity to speak out about what she believed to be true, “there was nothing she thought worth having that her silence would buy.”

“Your silence will not protect you,” Lorde warned her audiences, in person and on the page. With these two new editions of her work, her voice resounds, a writer who is easy to quote but whose self is impossible, in the end, to distill into a catchphrase. Black. Lesbian. Mother. Warrior. Poet. Audre Lorde insisted on being recognized for who she was. More important than names she answered to, and the slogans she is known by, are the stories she tells, in poetry and prose, about how she came to be. These volumes take readers beyond the maxims and into an inner world where shame is useless, anger is sobering, and silence is a stranger.