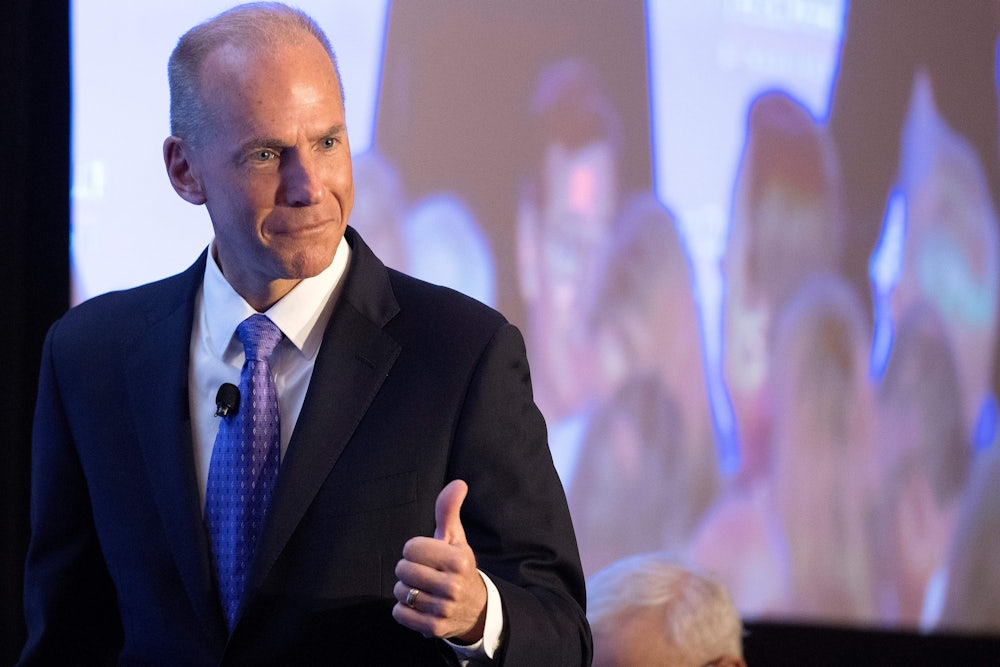

In December 2019, reeling from the growing fallout of two crashes that killed 346 people, Boeing fired its CEO, Dennis Muilenburg. While he departed in disgrace, he was hardly frog-marched to the exit: The former chief will receive $60 million in stock options and pension benefits. And his time in the corporate wilderness hasn’t been long. Two years after the crashes of Lion Air Flight 610 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, both of which involved Boeing’s 737 Max planes, Muilenburg is back, running a vaguely defined holding company in the aerospace and defense industry.

Muilenburg is now the CEO and chairman of New Vista Acquisition Corp. The new firm, which went public on Wednesday after raising $240 million, is a special-purpose acquisition company, or SPAC: a kind of blank-check financial vehicle that’s become a popular method for companies—including some run by sports and Hollywood celebrities—to facilitate mergers and go public without much of the scrutiny associated with an initial public offering. In this role, Muilenburg will be largely free from shareholder oversight—to the dismay of crash victims’ families.

“Dennis Muilenburg should be defending himself in criminal court right now as the lead conspirator in corporate homicide in two plane crashes,” said Michael Stumo, whose daughter, Samya Rose Stumo, 24, died in the Ethiopian Airlines crash.

Last month, the Department of Justice’s fraud division announced a $2.5 billion settlement with Boeing, in which the company admitted that two of its employees had deceived the Federal Aviation Administration about critical software in the 737 Max that helps to avert crashes. Thus ended the government’s criminal investigation into the two deadly crashes—and the chain of corporate, bureaucratic, and technical malfeasance that led to them. In the eyes of victims’ families, though, this agreement was a whitewash. The real blame, they say, lies not with two midlevel employees but with the executives who supervised them and oversaw a penny-pinching project designed to rush a slapdash aircraft to market.

And now, the CEO who oversaw the introduction of the 737 Max is returning to the same industry from which he was ignominiously dismissed.

To their critics, SPACs are inherently suspect—a shadowy, speculative instrument designed to bypass the due diligence ostensibly built into the IPO process. Using money raised from venture capitalists, private equity, hedge funds, or other investors, a SPAC is essentially a shell company formed to acquire other companies and take them public. The reporting requirements are exceedingly thin: A SPAC has to tell the Securities and Exchange Commission and investors which categories of companies it plans to pursue and little more. According to its SEC filing, New Vista will pursue companies from the “space, defense and communications and advanced air mobility and logistics industries”—all in line with Muilenburg’s experiences at Boeing.

With fewer regulatory measures in place to guide them, SPACs reward salesmanship and promises of investors reaping huge value somewhere down the road. That may be why SPACs often cater to futuristic-sounding industries—aerospace, renewable energy, cryptocurrencies, and other hyped technologies—and why they have attracted a range of speculators, especially since the beginning of the pandemic. “They’re incentivized, if anything, to get the deal done so they can get their 20 percent,” said Andrew Park, a senior policy analyst at Americans for Financial Reform, referring to the fact that SPACs give a fifth of shares to “sponsors”—i.e., founders and investors. “There’s no quality control.”

SPACs have become intensely popular, outpacing traditional IPOs in the last year. They benefit from well-connected and celebrity figureheads: Former baseball star Alex Rodriguez, basketball legend Shaquille O’Neal, and football player turned activist Colin Kaepernick have SPACs. Virgin Galactic—the nascent space-travel firm helmed by Richard Branson—went public via a SPAC. Along with the fantasy sports betting website Draft Kings, Virgin Galactic is often cited as one of the more successful examples of a SPAC. (It may be one of the only successful examples, as SPACs have a high failure rate.)

Boeing has settled lawsuits in relation to the Lion Air crash, but a variety of civil litigation is ongoing regarding the Ethiopian Airlines crash, and some lawsuits may eventually expand to encompass the company executives who oversaw the Max project. But for now, victims’ families must watch as Muilenburg, flush with tens of millions in compensation from Boeing and facing no criminal liability, now launches a potentially lucrative new venture. “This is what he’s attracted to: avoiding scrutiny and pumping up the profit margins,” said Stumo.

Andrew Park, the analyst from Americans for Financial Reform, recently submitted a letter to the leadership of the House Financial Committee recommending regulatory changes to bring more transparency to the SPAC market. In the case of Muilenburg, Park thinks that the former Boeing chief’s ability to raise $200 million in a SPAC offering reveals how flawed these shell companies really are. “This is someone who, in my opinion, has no credibility, and yet he can still raise a SPAC,” said Park. “I think that’s quite incredible.”