Massachusetts’s road to failure runs straight through the digital waiting room of the Democratic State Committee’s video calls. During long, slur- and expletive-filled gatherings, a vanguard of wizened Harvard alumni and outer-ring suburbanites screech over one another in a dread contest for Zoom-mic supremacy, hurling insults at the young, progressive, and racially diverse members bold enough to question the most basic tenets of their long-held rule. In a particularly unpleasant meeting last month, state committee apparatchiks moved to end the inquiry into the state party’s role in destroying Alex Morse, the young gay mayor from Holyoke who went up against the powerful chair of the House Ways and Means Committee, Ritchie Neal, only to have his reputation and career pummeled by a homophobic smear campaign ginned up by young politicos in search of an internship.

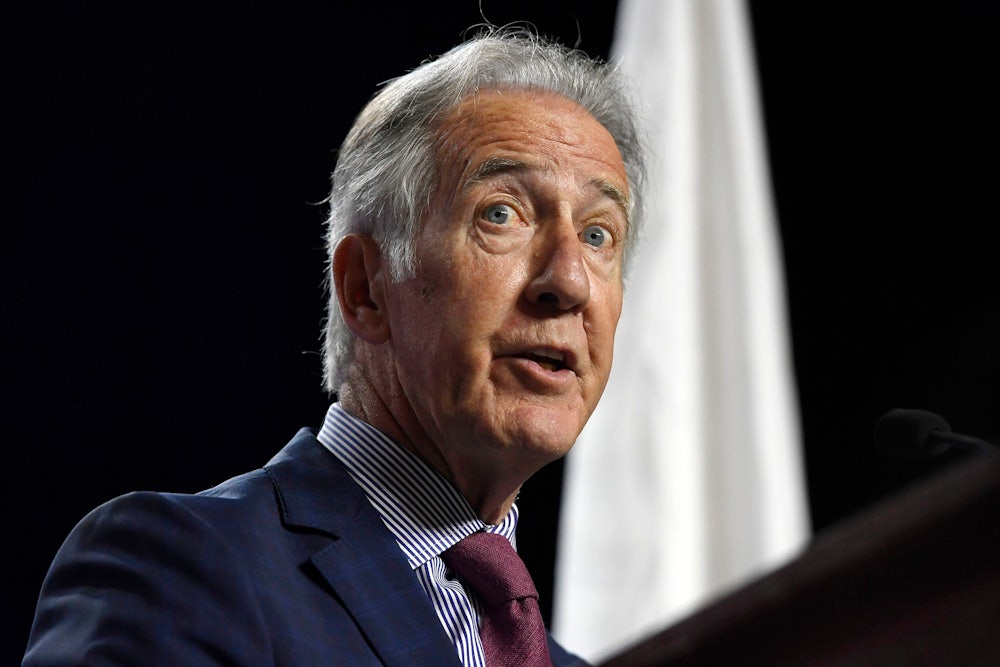

The disturbing behavior of the state Democratic Party’s varied membership may come as a surprise to political spectators whose bird’s eye view of Massachusetts leaves the mistaken impression that it’s studded with progressive firebrands like Senators Ed Markey and Elizabeth Warren and Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley. But at the Democratic State Committee’s end-of-January meeting, Markey made a special appearance to laud committee Chair Gus Bickford for his stewardship of the party and of the state. This was a shocking cameo: It was none other than Bickford who fanned the flames of the Morse smear campaign, who has had a hand in enabling Republican Governor Charlie Baker’s two-term tenure, and who cultivated a roster of conservative DSC members so horrified by Morse’s unprecedented threat to the sleepy status quo, and their power within it, that they leapt to protect his saboteurs.

Prior to the Morse scandal, the DSC was more content to simply ignore progressives than actively sabotage them. The organization’s membership is much closer in skill and temperament to an army of Rudy Giulianis than it is to a cabal of conniving Boss Tweeds. Markey’s laudatory remarks merely demonstrated the extent to which the state’s most committed progressives are compelled to do business with the cracked and anachronistic moderates who line the statehouse, governor’s mansion, and the top floor of The Boston Globe. Taken together, this is no party machine: It is a hopelessly atomized collection of actors, scrambling to maintain their political careers at the cost of a cohesive political vision.

As a result of this mayhem, Massachusetts ranks thirty-first in affordable housing and forty-seventh for income inequality in the nation. As of 2017, the average net worth of a Black family in Greater Boston was $8, and in cities to the north and south, between one in four and one in six residents live in poverty. The towns of Lynn, Lawrence, New Bedford, and Fall River rarely make the news, but when they do, it’s usually because their residents are struggling to make ends meet. Springfield, once a major manufacturing hub of firearms, textiles, and paper, now boasts the highest rate of asthma in the country, and in Boston’s Chinatown, the air quality is the worst in the state. (An instance of environmental racism rendered even more staggering by a recent report showing nearly 20 percent of deaths worldwide are attributed to air pollution.)

Failures on the part of Democrats to address the fallout from a half-century of deindustrialization and its outsize effects on Black, immigrant, and working-class citizens have only been exacerbated by Baker’s unflinching willingness to sacrifice human lives for the sake of Boston’s business-owner class during the Covid-19 pandemic, opening up restaurants and pushing for fewer restrictions even as the state’s food insecurity rises faster than any other’s. In carefully worded statements, state Representative Mike Connolly and other similarly cautious legislators have detailed the ways in which Baker’s belief in private enterprise as a universal panacea had positioned Massachusetts next to last for overall vaccine distribution:

If Massachusetts was its own country, we would have the worst per capita COVID death rate in the world—and unfortunately, that fact remains true as of this writing (with 212 deaths per 100,000 residents, according to recent figures tabulated by Johns Hopkins University). To put these numbers in context, the overall death rate in the United States is about 135 per 100,000.… According to figures posted Thursday evening by The New York Times, Massachusetts has so far only been able to administer about 53% of the vaccines that we have received from the federal government. This places us 48th in the nation in terms of overall vaccine distribution. Only the states of Alabama and Mississippi have been less efficient than us.

Data suggests substantial improvements have been made in the intervening time.* But the blame for Massachusetts’s cascading failures doesn’t fall on the individual sensibilities of Baker or Massachusetts’s progressive senators. After all, neither Markey nor Warren have been able to propel themselves out of the stupefying quagmire of the state’s politics on their own. Markey’s 2020 revival was almost entirely dependent on the bonds he forged in recent years with the Sunrise Movement. Warren would still likely be a Harvard professor had Harry Reid not tapped her to play an oversight role in Washington as millions of Americans coalesced in outrage over the 2008 financial crash. Neither has successfully built a coalition capable of challenging their state’s inert political institutions.

Jonathan Cohn, an organizer with Progressive Mass and dedicated chronicler of the state party, tells The New Republic that in order to understand why it’s so difficult for progressives to build power in the Bay State, one must first come to grips with Massachusetts’s underlying political ideology. “People think Massachusetts isn’t a terrain of conflict or struggle because they conceptualize conflict only through nationalized fights of Democrats versus Republicans, and we don’t have those kinds of fights because we have a nonexistent Republican Party and plenty of Democrats in our legislative supermajority whose voting records align with moderate Republicans,” he says.

This lack of polarization creates a political feedback loop in which progressives seeking to challenge and confront the stale hegemony of moderate rule find themselves without any real state-based mass movement to back their efforts. The resulting dismal success rate has sapped the motivations of progressive political aspirants. It’s no wonder that the most vital project to which Massachusetts’s youngest progressives pledged themselves was the cynical smearing of Morse’s character. Out-of-state reinforcements are in short supply as well. “You don’t have big donors or outside progressive groups mobilizing electorally here, because everyone’s under the impression that we’re all just living happily in this liberal utopia,” Cohn says.

“Then you also have Charlie Baker, who nobody is willing to attack outright,” he says. “Whether for his vetoes, or for his regressive stance on basic social welfare policies, everybody in the state is terrified of his approval rating, and so it keeps growing even as he continues to attack progressive policies and voices.”

In 2020, Baker held the highest approval rating of any governor in the country, following in the footsteps of other Republican governors like Mitt Romney who leveraged Boston’s corporate lobbies and the absence of a competent Democratic Party to maintain his lock on power. In the Senate primary last year, neither Markey nor Kennedy was willing to say that they would support a Democratic challenger to Baker; major progressive groups like Planned Parenthood and the Environmental League of Massachusetts have similarly refused to endorse a Democratic challenger out of fear of reprisal. After losing his 2010 election with a Tea Party–style campaign, Baker rebranded with a persona more closely aligned with the charter school bourgeoisie. Swapping political wardrobes secured his favor with Boston’s fiscally conservative Brahmin class in 2014; they reaffirmed their fealty in 2018.

“If you are a wealthy, educated, socially liberal person, you align with the Democratic Party in most places, but Baker is a great asset for your fiscal conservatism,” Cohn says. “This is the kind of person that really defines the voice of The Boston Globe editorial board: They represent the mindset of white, upper-middle-class, inner-ring suburbia—socially liberal but into the idea that a friendly Republican governor is a check on a runaway Democratic legislative branch.”

As Lily Geismer argues in Don’t Blame Us: Suburban Liberals and the Transformation of the Democratic Party, there is a strong argument to be made that Boston and its suburbs provided the ideal spatial and economic conditions to serve as the scaffolding for the national party’s most conservative leanings. In the highly segregated suburbs connected by the postwar construction of Route 128, academics and high-tech defense industry workers were fused into an upper-middle-class bloc by a military-industrial complex rapidly expanding outward from MIT’s labs and legitimized by the kind of liberal, if jingoistic, social scene swirling around Harvard Square cocktail parties.

These professionals endorsed socially liberal policies like busing and fair housing but only insofar as they didn’t integrate Blacks into their own suburbs. Once proposals for various kinds of integration started to creep out of Boston proper and into the 128 corridor, they were met with intense hostility. (It’s worth remembering that Massachusetts may have been the first state to abolish slavery outright, but it was also the first colony to legalize it.) The suburban liberals supported pro-business tax cuts as long they aligned with high-tech white-collar job creation, leaving the deindustrializing central and coastal towns to wither. The only state to go for McGovern in 1972 and Reagan in both 1980 and ’84, Massachusetts finally found a presidential candidate in its own likeness with Michael Dukakis, who, in an ironic turn, climbed into a tank and lost to Bush handily in a 1988 landslide.

Today, the suburban political outlook forged in Brookline, Newton, Concord, and Lexington is also the mentality that tolerates a statehouse controlled by a Democratic supermajority in theory but by the troika of governor, statehouse speaker, and state senate president in reality. The centralization of power in the weekly meeting between the three Boston bosses is enabled by rules and procedures that make the Massachusetts state legislature one of the least transparent in the country. (In 2015, the Center for Public Integrity gave Massachusetts an F for access to public information, a D for legislative accountability, and a D- for executive accountability.) This provides cover for Clinton-era “progressives” and Blue Dog hard-liners alike to pander to their respective bases without any real accountability for highly secretive votes.

Calla Walsh, an organizer with the progressive advocacy organization Act On Mass, has been organizing to expand transparency in the Massachusetts statehouse. She tells The New Republic that if progressives want to see change in the state, first they have to pull back the shades shielding Beacon Hill from public scrutiny. “Right now, committee votes are for the most part secret. That means that bills will sit in committee for years or get sent to study, where they die,” Walsh says. “That’s why we’re lobbying to have a 72-hour period before any bill is voted on where they are made available to the public, lowering the threshold needed for a recorded roll call vote, and making committee votes public.”

At the end of last year, the statehouse waited for the final days of the session to vote on a slate of high-profile bills. The late arrival of a police reform bill, weighing in at over 100 pages, gave members cover to vote against it under the pretense of not having time to read it in full. Now, hot on the heels of his veto of the Roe Act—which would have immediately expanded access to reproductive health care in the state—Baker has vetoed a sweeping climate bill for the second time, returning it to the legislature with a suite of kneecapping amendments. In a gesture mirroring his Janus-faced stance on the climate emergency, Baker signed the rejection on recycled paper.

Even when members of the legislature try to break the consensus forged by Baker and Democratic leadership, the speaker’s cudgel is used to punish dissent and rein in progressives who step out of line.

Multiple state representatives have spoken publicly about former speaker Robert DeLeo (who resigned last year) stripping members of their committee chairs for challenging his conservative agenda in the statehouse. While DeLeo managed to break the streak of the three preceding House speakers who left office under indictment, his chosen successor, Ronald Mariano, lined up the votes for his own speakership years before DeLeo’s resignation, winning the election handily along party lines almost immediately after DeLeo’s departure in a not-so subtle hat tip to the seat’s storied legacy of corruption.

In 2016, Massachusetts’s statehouse primaries were ranked last in the country for competitiveness. There’s little to no incentive for incumbents to challenge the speaker and fight for progressive policies. If they do, they are stripped of their committee chairs and the healthy stipend that comes with the job. The failure to advance progressive ideas comes with no consequences, as there are few viable progressive challengers moving through the pipeline of the atrophied state party. While a handful of representatives and state senators affiliated with progressive groups have pushed for drug legalization, subsidized housing, police reform, racial justice legislation, climate action, and eviction relief, they represent a sparse minority in a crowded field of Democrats who are content to ax bills in secret committee votes or send them to the purgatory of legislative study.

The lack of a vital progressive wing in Massachusetts’s state politics has had national implications. In addition to Ritchie Neal maintaining his chairmanship of the House Ways and Means Committee—where he has continued to wage war against Medicare for All, an end to surprise billing, and tax filing reform—other House districts have either become safe havens for tepid moderates or have been seized by young conservatives, taking advantage of the absence of a progressive bench.

Congressman Stephen Lynch, known for his anti-abortion and pro-charter school stance, has represented the Southie-anchored 8th Congressional District for two decades. Before arriving in Washington, Lynch was arrested for drunkenly attacking a group of Iranian students protesting U.S. intervention abroad, and went on to provide pro-bono legal counsel to a gang of white teenagers accused of violence and harassment of an interracial couple. Later, in 1996, Lynch would introduce a “gay panic” amendment to lower the penalties for homophobic hate crimes. The most notable piece of legislation forwarded by Congressman Bill Keating, a New Dem caucus member and 10-year incumbent representing Cape Cod, is H.R. 1814, extending the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate exemption to Christian Scientists.

In the 4th District, a young Jake Auchincloss—with the help of his mother’s expansive donor network, forged through her role as head of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and her cozy relationship to The Boston Globe—won Congressman Joe Kennedy’s former seat. Prior to his electoral victory, Auchincloss worked for Baker; he is viewed by progressives in the state as little better than a Republican in Democrat’s clothing. Recent additions to the state delegation, such as Seth Moulton and Lori Trahan, offer policies similar to their moderate Democratic colleagues in competitive Southern and Midwestern districts, albeit polished with a progressive sheen to reflect Massachusetts’s bleeding heart facade.

As Ezra Klein observed in relation to California last week, “progressive” states are often fraught with contradictions between the superficial image promulgated by the national media and the economic and social realities on the ground. The lack of attention afforded to these contradictions allows for the further erosion of progressive institutions in the very states that claim to be their champions. With Republican state legislatures in states like Arizona and Texas weaponizing Trump’s legacy to pass increasingly right-wing—and increasingly craven—policies, Massachusetts has failed to offer a rejoinder. No one seems to notice that despite being plastered with “RESIST” yard signs, the state is devoid of inspiration when it comes to developing a policy response to the rise of the far right.

During his second term as a state representative, Ed Markey fought for legislation to end part-time district court judgeships in Massachusetts and, by extension, the cycle of corruption whereby judges curried favor with the politicians who appointed them through the private practices they were allowed to maintain. In an episode that could easily have played out today given the perpetuation of concentrated power in the hands of the House speaker, Markey was stripped of his seat on the Judiciary Committee, his desk literally thrown out into the hall. As he then quipped, “The bosses may tell me where to sit, but nobody tells me where to stand.”

To transform Massachusetts into the progressive beacon it’s often mistaken for, Markey and his fellow progressives will have to break from the tradition of supporting incumbents at all costs, especially when they categorically oppose the most basic tenets of the progressive agenda. Like-minded liberals must support the same challenge to the status quo that Markey mounted in 1976, spending equal time fighting for left-wing legislation in Washington and energizing grassroots movements back home. During his 2020 campaign, Markey flipped the Kennedy script, declaring in his most celebrated ad, “With all due respect, it’s time to start asking what your country can do for you.” The joke landed, and Markey won a mandate with a 10-point victory. What Massachusetts is doing for its residents, however, remains unclear.

* This piece has been updated to reflect new Covid-19 data.