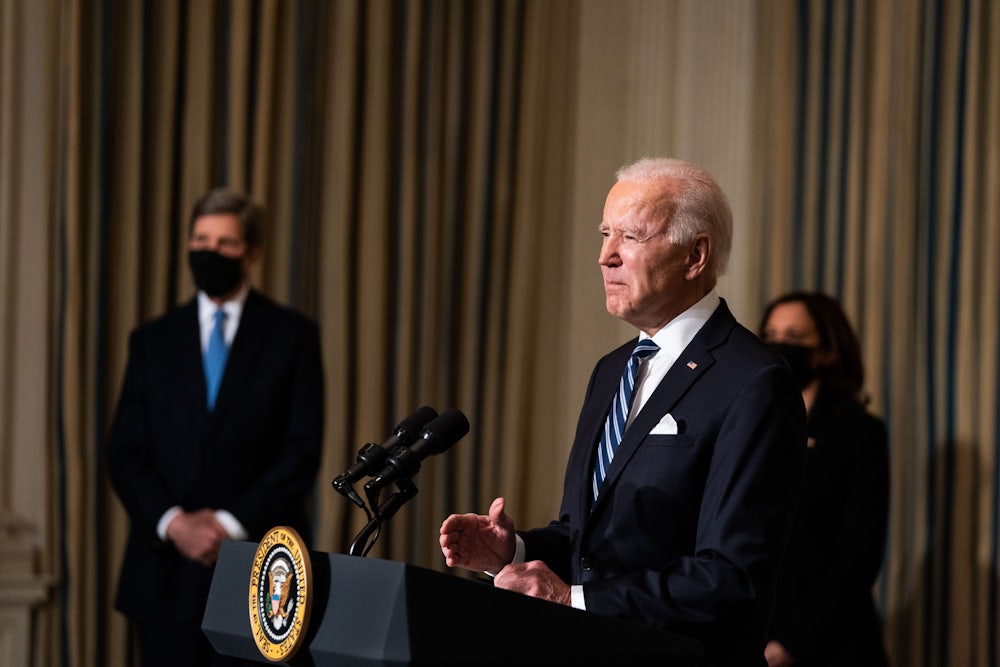

What does it mean to “elevate climate change as a national security priority?” President Joe Biden is already well on his way to keeping this campaign promise, tapping John Kerry for a new Cabinet-level “climate czar” position housed on the National Security Council and directing the intelligence community, last Thursday, to put together the country’s first National Intelligence Estimate on climate change.

These might sound like steps in the right direction. Biden’s been praised by climate groups for these and other climate-related measures in his first week in office, including pressing pause on many drilling leases, revoking the Keystone XL pipeline’s permit, and rejoining the Paris Agreement. But “security” has meant some troubling things to American politicians and the world over the past few centuries. And designating climate change a matter of national security may affect how we engage with institutions like the Paris Agreement or the very topic of climate change—for the worse.

Security can come in many forms. One approach, collaborative security, is the kind of security that a community with herd immunity has from an infectious disease: Each person is protected by the protection others have. A society that prioritizes this kind of security works to build social safety nets, ecological protections, and social insurance schemes—policies that benefit the collective and can also reduce the kind of pressures and anti-social sentiments that inspire harm and violence in the first place.

The other approach is much less sociable. Let’s call it “antagonistic security.” This strategy wins security by protecting one group from others—“us” versus “them.” A society that prioritizes this kind of security works to build armed forces, competitive advantages over presumed and imagined rivals, and prisons. This is the kind of security those patrolling a barbed wire fence have from those trapped within it. This approach is built into the institutions that defend the “national security” interests of modern countries. Today, in the wake of the January 6 insurrection, the United States Capitol building is surrounded by miles of literal fencing with razor wire, which the Capitol Police chief has argued should be made permanent.

These are two very different ways of securing ourselves, our communities, and our interests. And both our safety and our freedom depend on which we choose: Doubling down on razor-wire politics will ensure that we fail to solve the political problems at the root of the climate crisis.

Antagonistic security has been the story of the modern world. From the voyages of Christopher Columbus to mass incarceration, modernity has been structured by social systems that protected those who stood atop hierarchies and marked the rest for exploitation and expulsion—an ongoing project. And much of American climate policy to date has likewise been built on the assumption that security is a zero-sum game. While President Trump made headlines by withdrawing from the Paris Agreement, Obama-era technocrats also defended corporate interests from more stringent and binding emissions targets that would have helped protect the entire world from climate disaster. This doesn’t just cater to industry donors or coal-containing swing states; it also replicates an antagonistic security model, treating the United States as the singular group to be protected from both the ravages of climate change and any economic costs of reducing them.

The point we have reached now—of mass extinctions, melting polar ice caps, extreme weather events, runaway carbon emissions, and a planet heating inexorably beyond habitability—is the product of this kind of politics. The Industrial Revolution itself, which first set us on this course, depended on exploitation and violence. Advances in coal production in Britain set the stage for our unprecedented carbon emissions, while British companies spun and wove cotton grown by the enslaved of the American South and eventually exported these products to the massive Indian market—conquered and secured by the British East India Company’s mercenary army. The combination exploited the linkages of trade built and maintained by the antagonistic security structure. And the tremendous boom in technology and fossil fuels to run it would one day produce the climate crisis.

And yet, for the most part, efforts to mitigate the damage caused by climate change and to reverse its underlying dynamics have mimicked the model of antagonistic security. Nation-states continue to “protect” their national interests from rivals rather than work for the common good of life on this planet. Never has this approach made less sense.

Climate change is definitionally a global problem, though one whose effects are experienced unevenly. It is not possible cleanly to separate a country, however powerful, from the world. The attempt to make pollution “someone else’s problem” on a planet we all live on together is deeply delusional: Neither atmospheric carbon nor the social problems it exacerbates are contained by borders. It is in every country’s “national interest” and every corporation’s private interest for everyone else to do the heavy lifting while it reaps the atmospheric rewards. But if everyone acted from this principle, no one would do the work we all must do to meet the challenges of climate crisis. Thus, beyond the fact that militaries and military conflicts are dramatic sources of emissions themselves, they also promote and embody the kind of politics that drive us further from sensible climate policies and actions.

What’s more, this approach is deeply immoral. The impacts of climate crisis are perversely distributed: The entire African continent has only contributed 3 percent of global emissions, yet is already reeling from cyclones of historic intensity and the loss of arable land. Small island states and Indigenous nations face existential crises from sea level rise and pollution. Yet an approach to climate crisis based on “national security” foregrounds how climate impacts will affect us, which works to background questions of national responsibility for the effects others will face.

Collaborative politics is our only way out. Collaborative climate politics is broadly redistributive. Responding to the full history that caused the present situation—meaning not just different levels of emissions but also the imperialist and exploitative practices they came from—could both help solve the climate crisis and help undo systems of oppression. The possibility of this accomplishment has led scholars, activists, and other intellectuals to call for “climate reparations.”

These dreaded r-words—racism, redistribution, and reparations—trigger alarm bells, especially in our increasingly polarized political environment. But we should notice that business as usual already redistributes: It simply redistributes in a way that replicates rather than counteracts injustices under racial capitalism. As law professor Dean Spade noted in The Nation in December, everything from corporate tax breaks to prison and police spending already facilitates massive upward redistribution, at the expense of food, health, and housing vulnerability.

Reparations simply redistribute better. Rich states and corporations of the world (particularly former colonizers and fossil fuel corporations) must take up their fair share of the work. That includes lowering their own emissions, removing the carbon they spilled into the atmosphere, addressing loss and damage this history is already causing, and helping to resettle the many it is displacing.

Collaborative climate politics would redistribute power over important decisions, not just resources. It is no accident that our current system shifts risks in the way that it does. Over the past year, state legislators have been hard at work to escalate criminal penalties for anti–fossil fuel activists and even the organizations that support them, following model legislation produced by the American Legislative Exchange Council, a right-wing lobbying organization funded by billionaires and large corporations. Generally, the elites who stand to benefit from the poverty and insecurity of those without power have captured the lawmaking, regulations, and even the popular politics that might otherwise challenge their exploitation.

Some shifts can happen within existing institutions. We could reshuffle voting rights at important multinational institutions like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, so that 85 percent of the world’s population no longer has a minority share in the institutions that shape global flows of financial resources. And we could insist on controlling serious amounts of climate funding through participatory budgeting or sortition processes—which give communities direct control over portions of local budgets and lawmaking processes, respectively—rather than leaving them to institutions controlled by moneyed elites.

But we would have to build some things from scratch. One way to do that is through the concept of community control. Community control means just what it says: allowing communities the rights and resources to decide for themselves how they will meet their needs with land, housing, and education. Groups like the international Energy Democracy Alliance call for “energy democracy.” Public ownership of utilities could, as the Energy Democracy Alliance calls for, “accelerate the renewable energy transition at the scale needed to meet our closing climate deadline” by cutting out the private interests that defend their bottom line at the expense of both communities and the planet.

This collaborative approach would directly address the patterns of vulnerability and deprivation that the history of conquest and domination etched into our economy and politics. It would also be a much more effective way of fighting climate change than the current plan of waiting for someone else to act. It would approach climate change not by waging yet more wasteful antagonistic wars of vengeance or plunder but by building collaborative security structures that protect and are accountable to everyone. Since this approach would have to address our political and economic structures at their most basic level—whom and what our systems are built to protect—this effort would effectively remake the world. This time, we can build it justly.