When Washington, D.C., announced that it would soon prioritize people who are overweight for the Covid-19 vaccine, experts and commentators were perplexed. Nate Silver tweeted that “there’s basically no prioritization at all.” Others questioned the utility of using such a crude measure as body mass index, with its checkered history, as an indicator of health. Some worried the policy would prioritize overweight young people and smokers over the elderly or those with more pressing conditions like diabetes.

This debate reveals the broader problems facing states and municipalities when it comes to prioritizing the vaccines. The difficulty lies not just in identifying accurate scientific risk factors like medical conditions and underserved demographics but also in identifying and notifying those most at risk.

D.C.’s vaccination plan isn’t as odd as some first thought: The city plans to introduce a tiered system for medical vulnerabilities, placing those with a few extra pounds after people who have cancer, kidney disease, heart conditions, and other serious illnesses. Although half of the District qualifies as overweight, the new priorities will also kick in only after health workers, the elderly, teachers, and other frontline workers are vaccinated, which will likely reduce the pool of those who would qualify with this medical condition alone. And there’s actually a good deal of evidence that additional weight—even if you are young and even if you are not considered obese—does put you at greater risk for developing severe Covid-19. D.C. simply seems to be looking ahead, beyond current national recommendations, for assessing risk. And in particular, this plan might offer advantages in terms of addressing long-standing health inequities.

Although the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has offered recommendations on which groups to prioritize for vaccination, it’s up to the states to make their rules. Alaska will soon widen its age limits to prioritize those 55 and older, as well as those with two or more high-risk health conditions and those in “unserved communities.” Florida is vaccinating those above 65, as well as patients considered by hospital providers to be extremely vulnerable. And earlier this week, California announced it would change course with a new age-based system, possibly pushing essential workers further back in line.

The science on Covid-19—who gets it, who grows sickest, and why—is still evolving rapidly. But only a few months after the United States started seeing a rise in Covid cases last spring, researchers and practitioners pinpointed a surprising commonality: The higher your body mass index, the greater your chances of suffering worse outcomes from Covid-19. One study found that Covid-positive patients with obesity were 113 percent more likely to be hospitalized, 74 percent more likely to need intensive care, and 48 percent more likely to die. But it’s not just those with obesity, with a BMI of 40 or more, who are at risk: Researchers in the U.K. found that risks begin going up for those who are overweight with a BMI greater than 25, as well. One preprint study, which has not been peer-reviewed or published in a journal, found the majority of patients hospitalized for Covid-19 were either overweight (29 percent) or obese (48 percent). And another study found that hospitalized patients with overweight (in health industry terminology) were actually at greater risk of dying (40 percent) than those with obesity (30 percent).

There are a few possible reasons for this, ranging from the physical to the social. First, those with obesity frequently have lower immune responses, chronic inflammation, and tendency to form blood clots—all factors that can make Covid-19 worse. In addition, obesity is often linked to other serious health conditions, like heart disease or diabetes—but stigma often causes people to forgo medical care in general, making other aspects of their health worse and making them less likely to seek care immediately for Covid-19. These conditions are overwhelmingly common in the U.S., where 40 percent of people have obesity and 32 percent have overweight.

While the CDC says being overweight may increase the risks of severe Covid-19, it’s not part of the official recommendations for vaccine prioritization yet. But a report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, which has helped inform these policies, recommends that medical conditions like these posing moderate risk should take priority in the next phase, after vaccinating health workers, the elderly, frontline workers, and others at high risk.

Dr. Helene D. Gayle, president and CEO of the Chicago Community Trust, was the lead editor on the National Academies report. The evidence has become clear, she told me, that obesity is not the only weight risk factor. “Even people who are overweight, over 25 BMI, are at greater risk of severe disease.” That being said, she added, those on the lower end of that spectrum “probably shouldn’t have a higher priority than somebody who has severe heart disease, because that person with severe heart disease is probably at greater risk for a bad outcome.” Creating tiers within each category, as D.C. says it plans to do, helps prioritize those with the greatest needs first.

But there’s another way BMI might be useful in getting vaccines to at-risk individuals. And that has to do with complicated issues of privilege and under-service that are often very hard for public health initiatives to correct.

Certain communities, particularly those frequently neglected and marginalized in the health care system, are in greater danger of disease and death. “We have to follow the data. And when we follow the data and prioritize based on who’s dying and who’s getting this disease most, it’s going to take you to communities of color, unfortunately,” Dr. Christopher King, chair of the health systems administration department at Georgetown University, told me. There are other factors that also make many of these communities more vulnerable, he said, from large, densely populated apartment complexes to a high number of people of color working on the front lines throughout the pandemic. “People of color have been historically marginalized, not having access to the same level of resources as their white counterparts,” said King. “So this is a public health issue—if we don’t distribute the vaccines in communities that are hit the hardest, we’re going to have a tougher time overcoming Covid. We need to be sure that that’s where we start.”

And, in fact, that’s what the National Academies report recommended. “We said that those areas, geographically, should be prioritized,” Gayle told me. Targeting vaccinations based on neighborhoods alone, however, has already proven tricky. First, it’s politically sensitive. Dallas County, for example, abandoned its plan to prioritize vaccination of “people living in the county’s most vulnerable ZIP codes, primarily in communities of color,” after state officials threatened to slash funding, according to the Texas Tribune last week.

Where officials have managed to prioritize at-risk communities, there have been some reports of more privileged individuals gaming the system. In New York, there have been reports of people traveling, sometimes for hours, to line up for vaccinations in some of the hardest-hit neighborhoods. Some places, like Prince George’s County in Maryland, have tightened restrictions on who can receive the vaccine after residents of nearby counties took up vaccination slots. However, enforcement is difficult and time-consuming in an already overstretched health system.

Focusing on underlying conditions and reasons for higher rates of Covid-19 severity and death could be one effective way to address some racial and socioeconomic inequities—which neither simple age metrics nor longer lists of more specific conditions necessarily do. In the D.C. neighborhoods most affected by Covid-19, nearly three-quarters of residents qualify under the overweight and obesity priorities, compared to half of the city as a whole. The National Academies report found that obesity was one of the top three risk factors for people of color, alongside heart and kidney failure. King cautions his students not to put too much emphasis on BMI alone. “You have to take a lot of considerations—bone structure, race, ethnicity, history,” he said. “A lot of cases would be at the doctor’s discretion to define what that looks like for the patient.” But it can be one tool for helping assess health risks.

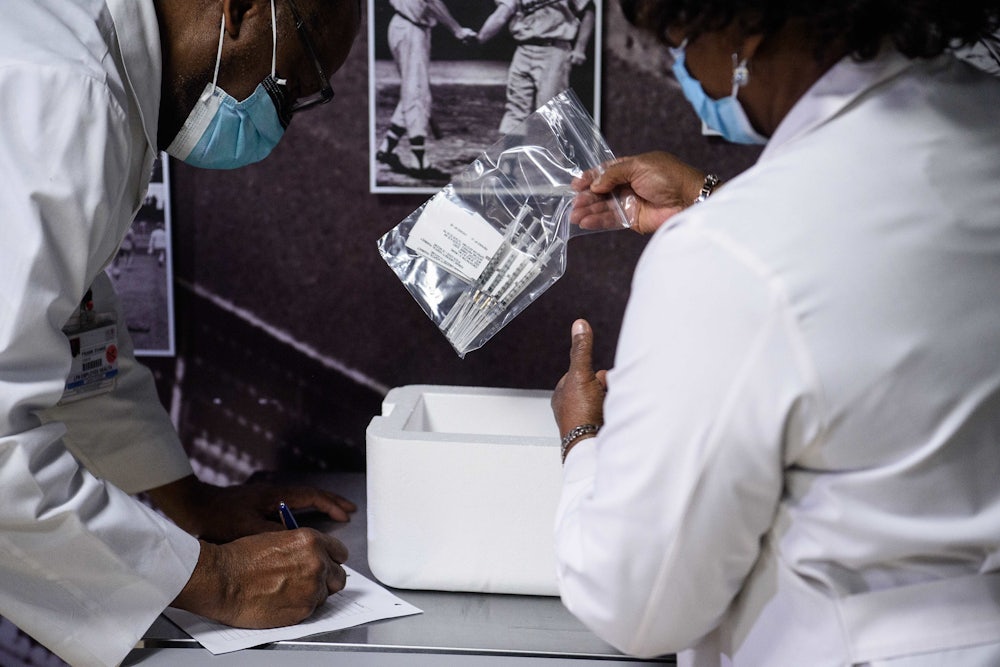

Currently in D.C., which is still in the phase of vaccinating health workers and those above the age of 65, the neighborhoods with the lowest rates of vaccination have some of the highest rates of Covid-19 cases. For King, the unequal distribution demonstrates the barriers even to learning about the vaccines, let alone registering for and receiving them. “I think the most significant contributor is having access,” he said. Doctors, health clinics, and insurance companies should be reaching out to those who qualify to let them know where and when they may be vaccinated. “They shouldn’t have to travel to receive the vaccine; the vaccination process needs to be set up in a way that’s convenient for people,” he said. And the people administering the vaccines need to be a part of the community, he added, to help answer questions and address any hesitations.

To a certain extent, the choices communities and counties are facing right now are an artifact of a poorly directed national response. “We have very limited amounts of vaccines available because of poor planning on a national level, and it’s causing the mayor and the council to make some tough decisions around risk and who needs to be at the front of the line,” King said, noting that expanding the supply of vaccines, eliminating bottlenecks, and communicating about which factors put people more at risk will help. “Whatever you do, somebody’s going to have an opposing position. But from what I’m seeing, the city’s doing the best they can with the limited resources that we have.”

It’s important to make sure those who need the vaccine the most are getting it. But it’s also important not to waste incommensurate energy on the chance that people will abuse the system. “When there’s scarcity of something that is as important as this vaccine, we know that there are going to be people who will jump the line,” Gayle said. It can be disheartening when others are abusing the process. But in a vaccination effort this large and this urgent, reaching out to those who need it most is worth the risk of a few bad actors taking advantage of the moment to act unethically. And public education is probably more effective than focusing on preventing every single case of line-jumping: “We have a large role to play in educating the population, so that we really do see this as something that we’re all in together,” Gayle said. The more we show the reasoning behind changes in prioritization like these, the easier it may be for all of us to follow the rules—and we’ll all be better off for it. Ultimately, vaccinating those at highest risk first isn’t just the moral thing to do. It also helps all of us.