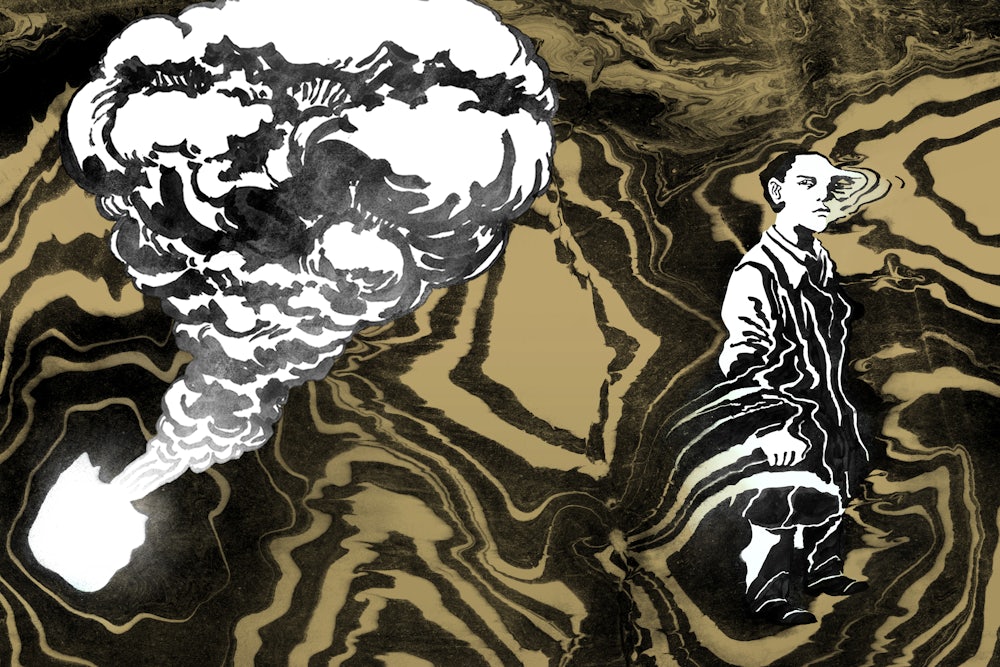

In 1997, the historian Iris Chang published her important, incendiary book The Rape of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II. It was a vital work of salvage, resurrecting for a new generation the half-forgotten savagery unleashed on Chinese citizens by the Japanese Imperial Army during its march across Republican China in 1937. An unmatched researcher and unyielding advocate, always elegantly besuited, Chang was embraced by many Chinese and Chinese-Americans who hadn’t known much more about the slaughter at Nanking than what they heard as family lore. For them, Chang’s devotion to unearthing buried memory was redemptive, and they elevated her into a kind of oracle.

Perhaps surprisingly, Chang’s efforts resonated far beyond the people whose lives had been directly touched by the soldiers’ crimes; The Rape of Nanking became a bestseller in the United States. Filled with exhaustive depictions of the most depraved forms of cruelty ever enacted, it seemed an unlikely hit. Consider the following account of the Imperial Army’s sexual violence, representative but hardly the most shocking:

Perhaps one of the most brutal forms of Japanese entertainment was the impalement of vaginas. In the streets of Nanking, corpses of women lay with their legs splayed open, their orifices pierced by wooden rods, twigs, and weeds.… [One] Japanese soldier who raped a young woman thrust a beer bottle into her and shot her. Another rape victim was found with a golf stick rammed into her.… Little girls were raped so brutally that some could not walk for weeks afterwards. Many required surgery; others died.… In some cases, the Japanese sliced open the vaginas of preteen girls in order to ravish them more effectively.

To write the book, Chang had suspended herself for years in the ruins of 1930s Manchuria, a far cry from mild Sunnyvale, California, where she lived. Her approach was rigorous to the point of obsession. She considered every artifact, no matter how mundane or horrible, necessary evidence: the statement of the trembling witness, the matter-of-fact diplomatic cable, confessions, diaries, reels of film, photographs all the grimmer for having no color, scholarly accounts, the deadening data of death tolls. Most important were the interviews Chang (who trained as a journalist) conducted with living survivors, some of whom still bore scars or limps. “I spent several hours with each one, getting the details of their experiences on videotape,” Chang explained of her method. “Some became overwrought with emotion during the interviews and broke down into tears.”

Everything Chang documented she had to review; ponder; return to throughout the stages of writing, editing, and proofing; and finally talk about, in the hundreds of lectures she gave across the world. It became, Chang admitted, “almost impossible to separate myself from the tragedy.… The stress of writing this book and living with this horror on a daily basis caused my weight to plummet. I had to write it, if it was the last thing I ever did in my life.” That she had previously struggled with depression did not make it easier. Her mother, Ying-Ying Chang, observed her daughter’s despair: “Iris told us that the most difficult thing was to read one case after another of the atrocities…. She read hundreds of such cases. She felt numb after a while. She told me she sometimes had to get up and away from the documents to take a deep breath. She felt suffocated and in pain.”

Seven years after The Rape of Nanking appeared, Chang was recording the stories of Filipinos and Americans who had endured another Japanese war crime, the 1942 Bataan Death March. Several months into the research, on a November morning in 2004, she left her sleeping husband and child at home, drove west into the oaky hills of Santa Clara County, and, on a lonely gravel road, shot herself. She was 36 years old.

The phenomenon of the historian traumatized by history remains unstudied and is not widely known. Yet anyone who has documented depravity knows the symptoms. After writing a book on the Armenian Genocide, a process that took me five years, I found it impossible to slip comfortably into sleep. All kinds of catastrophes visited me—still visit me—in that space before dreams: ugly visions, jarring scenes from my research. And I am not alone. In several extensive interviews I conducted with historians working across different subjects, and in the responses to a questionnaire I distributed to a dozen scholars (most of whom were reluctant to speak publicly about these most personal experiences), I discovered a reservoir of pain that reveals itself through symptoms familiar to anyone diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder: insomnia, rapid weight gain or loss, abuse of booze or pills, unexplainable anger or fear, paralyzing anxieties. Some reactions are more subtle: the sudden unwillingness to watch a particular film or read graphic news reports; claustrophobia in a crowd.

Traditionally, we’ve supposed that these kinds of reactions would afflict only firsthand witnesses to violence: the victims, the bystanders, maybe the journalists. And we are blessed with a rich literature of witness; every mass traumatic event has its own set of survivors elevated by personal experience into authorities. Historians, by contrast, have neither seen nor heard the catastrophes they study—they’ve reached them through imagination and immersion.

Can you be traumatized by something experienced only secondhand? According to a psychoanalytic framework, trauma is a shock so overwhelming that it cannot be mentally processed. It shreds our psychic defenses, compromising our customs, ideologies, religious beliefs, moral systems, rituals, close relationships, even the body itself. When stripped of its organizational protection, the mind struggles to assimilate things that would otherwise seem normal, futilely trying to make sense of that which it finds incomprehensible. All kinds of destructive and alienating behaviors result.

As first responders to and theorizers of trauma, psychotherapists and other mental health professionals are dangerously close to the sources of the pain they treat. The first hint that therapists might become traumatized by close interaction with their patients was raised by Chaim Shatan, a clinician-activist who worked closely with veterans ravaged by the Vietnam War. “We should be forewarned,” he wrote in an influential 1973 article. “We, too, may have nightmares; we, too, may be unable to sleep, unable to talk normally to other people for days or weeks. Once we professionals admit the knowledge of the veterans into our awareness, we are changed in fundamental ways.” In 1995, the clinical psychologists Karen Saakvitne and Laurie Anne Pearlman gave a name to the disorder Shatan identified: “vicarious trauma.”

Only in recent decades have psychotherapists sketched the borders between vicarious trauma and the more well-known problems of “burnout” and “compassion fatigue,” which constitute a sympathetic identification with a traumatized person. Such reactions can be repaired by sleep, exercise, a holiday, the company of loved ones. Vicarious traumas, by contrast, cut much deeper than emotional exhaustion, and are not so easily healed. The therapists are not subject to that moment of terror, but they feel it as though they had been. They become infected, as it were, as horrors are psychologically transmitted from one person to another.

Crucial to the process of vicarious traumatization is imagination, the engine of empathy and “the best guide,” in the words of the psychoanalyst Ghislaine Boulanger, “to entering experience that is beyond recognition.” For historians, documenting the past without imagination is impossible. It is the key to re-creating the ambience of other lives and the method by which scholars probe alternative futures. In his posthumous 1946 work, The Idea of History, R.G. Collingwood insisted imagination was the historian’s chief tool. Hannah Arendt called it an “inner compass,” a way to “catch a glimpse of the always frightening light of truth.”

The importance of imagination creates a double bind for the historian: The more fervent, precise, or visionary their reconstructions of the past, and the more completely they immerse themselves, the more harshly they may be wounded by what they study. But they also encounter a troubling paradox. When they venture into periods when a society has totally collapsed or a moral world been turned upside down, it is more difficult to understand what has happened. Scholars of genocide, for example, have long struggled with the problem of how an elite or a majority can be enlisted to annihilate an entire people. The nature of evil, whether radical or banal, still perplexes us. As Alan Bullock, the author of the masterful biography Hitler: A Study in Tyranny, told The New Yorker: “The more I learn about Adolf Hitler, the harder I find it to explain.” These failures to comprehend not only heighten historians’ trauma, they also fly in the face of the very idea of history as a discipline, which is predicated on the conviction that everything is knowable, or at least traceable, reconstructable. Doubt or confusion feels perverse, a betrayal of the victim.

Historians are distinct from survivors in another way: They return to the source of their trauma by choice. The descendants of genocide survivors, the children of torture victims, the spouses of social workers or firefighters—or, lately, those doctors and nurses in the vanguard of the fight against the Covid-19 pandemic—have no say in their condition. Whereas every day, sometimes for decades, historians open themselves, if not willingly then by a sense of obligation, to the pain of the past. Often, the present intrudes, exacerbating the trauma. After 9/11, Kristen Alexander, a visiting fellow at the University of New South Wales, Canberra, developed an acute fear of flying that worsened during her later work on a book about Australian airmen in the Second World War. She became depressed as her project intensified her fears. “I had nightmares and cried every time I read or edited the sections relating to the [airmen’s] deaths,” she told me. In her mind, “flight equaled death.” Many historians working on the Armenian Genocide, including me, remain deeply troubled by the 2007 assassination of the courageous Turkish-Armenian intellectual Hrant Dink in Istanbul. Historians examining slavery’s legacy are forcibly reminded of their subject when cops kill Black people with smug impunity.

It is bad advice to say that politics, sex, and religion ought to be kept out of polite conversation, but nobody wants you to bring up a genocide at a dinner party. “The extent to which my research is ‘dark’ and therefore not polite dinner conversation means I’m repeatedly isolated in piecing through the material,” Elena Gallina, a Rhodes scholar at the University of Oxford and researcher of sexual violence in wartime, told me. The burden of the work, of “sitting with the facts and figures,” as Gallina put it, “is made heavier by societal distaste for these things.” Where is the historian to go with her condition? It’s difficult to raise the problem over coffee, at faculty meetings, with students or publishers. Other disciplines have found ways, however insufficient, of containing and treating vicarious trauma. Psychotherapists are obliged to undergo supervision, where they discuss their clients; they may choose to see their own therapist. Social or medical workers can have their mental needs tended by their institutions.

But there is little recourse for the historian—beyond whatever mental health care they are eligible for at their institutions—in part because their trauma is so specific and so little understood, and their bosses and administrators are unlikely to offer comforting shoulders. Awareness of vicarious trauma, however, is growing in other related fields. A 2003 study revealed, for instance, that lawyers who work with criminal defendants or victims of domestic violence suffer secondary trauma and burnout at significantly higher rates than those who provide other “frontline” services. And in a world first, a state court in Australia awarded 180,000 Australian dollars in damages to a journalist who broke down after she spent 10 years reporting on court cases dealing with violent crime. Her employers, the court found, had breached their “duty of care to staff” by not providing her with any psychiatric support.

At worst, historians’ confessions of mental anguish are met with dismissal: Edward Gibbon wasn’t vicariously traumatized by writing The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire—so what are you, weak? In countries with privatized health care systems, scholars openly discussing their traumas might risk not receiving care, not being granted insurance, or compromising the professional networks they belong to, which depend on mutually enforced silence. “This spells the end of our professional pseudo-neutrality,” the clinician Chaim Shatan warned when first identifying the syndrome that would later be called vicarious trauma, “a departure from our long-cherished tradition of emotional imperturbability.”

Many historians, especially those working in academia, are taught that neutrality in all things is a first principle never to be violated. Some historians criticized Iris Chang, for example, for getting too close to her subject, for being too emotionally open to the material. But the cool, analytical distance the discipline recommends can very easily slip into dissociation, to too much distance—a way to ward off the possibility of vicarious trauma. Dissociation, as the psychoanalyst Richard Gartner writes, is usually “maladaptive, developing into an individual’s go-to defense against feelings of anxiety.” It leaves people “with only a partial understanding” of whatever they’re trying to make sense of. The balance between objective detachment and empathetic understanding—both essential for the practice of history—can be very difficult to attain.

If the historian—the very person supposed to process the past on behalf of everyone else—struggles with trauma, then it is little surprise that societies as a whole struggle to face the violence of how they were formed and how they prevailed, and find themselves riven with absence and silence. Every nation and political culture, after all, is built on the instinct to divorce itself from anything uncomfortable. Dissociation becomes an automatic political and cultural reflex, a way to avoid the proper consideration of earlier horrors and therefore evade responsibility for them. “Care must be taken,” Sigmund Freud wrote dryly at the beginning of the last bloody century, “to eliminate from the memory such a motive as would be painful to the national feeling.” To engineer a usable history, in other words, we stifle anything disquieting to the conscience.

There are other ways societies defend against even the threat of trauma. As with some popular literature and films on the Holocaust (from The Tattooist of Auschwitz to The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas to the 1997 movie Life Is Beautiful), we use kitsch and sentiment to guard ourselves, to lessen the blow. Perhaps more disturbingly, a proper reckoning with mass violence can be perceived by a country’s ruling power as a challenge. Due consideration of victims can be portrayed as a threat to the entire social order. In this way, an untenable status quo is defended, and the historian is faced not only with the trauma of the original violence but also with the official denial of that violence. Turks still think of Armenians as an existential menace, as do Indonesians of “communists.” Indigenous peoples everywhere face such a double demonization. Their pain is considered not only necessary or unavoidable, but dangerous, too.

The form of that pain also matters because the worst abuses are often the most intimate. For us to dwell on specific instances of children torn from their parents or women forcibly castrated at the Mexican border breaches our most tightly held taboos. The more invasive the violence, the easier it is to avoid discussing it publicly.

And yet in spite of these evasions, or perhaps because of them, historians persist. In every conversation I had with the scholars I interviewed, I asked: Why do you continue? A few speculated that they are simply better constitutionally equipped than other people to endure stories of cruelty—hardier or less emotionally susceptible by nature, maybe. Many said they feel a duty to give voice to the voiceless, as Iris Chang did. To see the children and grandchildren of catastrophe mended by their efforts reassures them that the work is worth something.

Others told me that their efforts to construct a narrative, to make some sense out of the incomprehensible, was therapeutic in itself. The precedent handed down to us by survivors and observers is critical, too. Their ability to make order out of catastrophe, to bring shape to that which is unfathomable, serves as both motivation and solace. In cases of enormous injustice, they provide the fuel for righteous and redemptive anger. Primo Levi’s and Elie Wiesel’s accounts of the Shoah, along with László Nemes’s film Son of Saul; Solzhenitsyn’s infamous gulag memoir One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich; Solomon Northup’s Twelve Years a Slave; Joshua Oppenheimer’s extraordinary documentaries The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence; or John Hersey’s Hiroshima: Whether verbatim testimony or fictionalized re-creation, such accounts act as a guide and orator for the imagination, illuminating a path so that the reader might enter a darker world without too much risk. These are but a sampling, but each of these texts serves this essential role.

It may be a comfort to know that for historians healing is possible. The “cardinal indicator of emotional maturity,” Shatan wrote in 1973, is “the capacity to be openly affected by another’s emotions.” He might have added, “without being broken by them.” Faced with terrible wrongs, observing others’ pain, how do you feel enough without feeling too much? The problem afflicts historians because they are human. Repair and restoration can take decades. It may never be completed. And the first step is the most daunting of all: to stare the original trauma in the face, to accept its unremitting gaze.