A good rule of thumb over the past five years is that if something strange can happen, then it probably will happen. One of those strange things happened earlier this month when the Democrats won two Senate seats in Georgia, giving them exactly 50 votes in the 100-member chamber. With Vice President Kamala Harris serving as tie-breaker, the Democrats managed to secure a functional majority in the Senate—and with it, simultaneous control over Congress and the White House by the thinnest of margins.

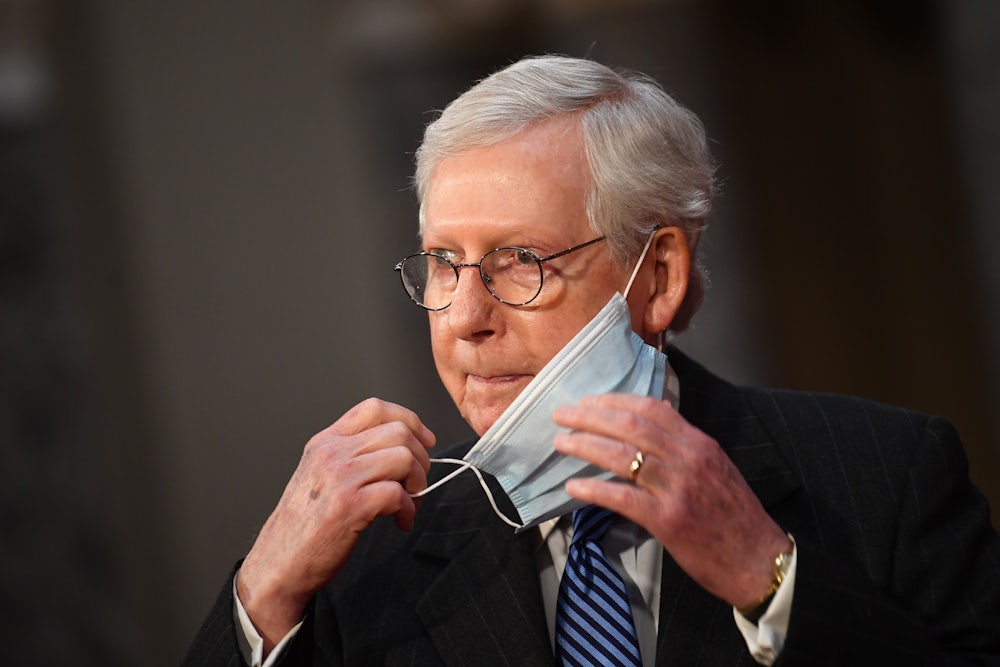

The last time this happened, in 2001, Democratic and Republican leaders jointly worked out a way to keep the Senate functioning. This time, Mitch McConnell is throwing a wrench into the plan: He wants Chuck Schumer, the Senate majority leader, to commit to giving McConnell an effective veto over the entire Democratic legislative agenda. It is, in many ways, vintage McConnell: He’s testing his limits; drawing lines in the sand. He also may be making this demand at a precarious moment, and ensuring that the gains he’d like to achieve perish as a result of his own actions.

“Twenty years ago, faced with the same scenario, the two leaders brokered a power-sharing agreement so the institution could function smoothly,” McConnell said in a floor speech on Thursday. “The Democratic leader and I are discussing a similar agreement now. I’ve been heartened to hear my colleague say he wants the same rules from the 2000s to apply today. Because certainly 20 years ago there was no talk of tearing down long-standing minority rights on legislation.”

The “minority right” to which McConnell referred is the filibuster, a controversial Senate rule that allows senators to block legislation from going forward unless it meets a 60-vote threshold to end debate. McConnell called it “a crucial part of the Senate” and noted Biden’s support for it. “So if the talk of unity and common ground is to have meaning,” he continued, “and certainly if the rules from 20 years ago are to be our guide, then I cannot imagine the Democratic leader would rather hold up the power-sharing agreement than simply reaffirm that his side won’t be breaking this standing rule of the Senate.”

Here’s the catch: The “power-sharing agreement,” as McConnell calls it, is the organizing resolution that normally gets passed at the start of every new Congress. Among other things, it sets out the committee memberships and party ratios of each committee. Without it, those committees are still technically led by the Republican chairs from the last Congress with rosters that favor GOP control. For example, Alejandro Mayorkas, Biden’s nominee to lead the Department of Homeland Security, will be questioned next week by a committee led by Wisconsin Senator Ron Johnson, a Republican. As Politico noted, this state of affairs may even prevent his nomination—and those of other would-be Biden appointees—from reaching the floor until it’s resolved.

So if Democrats control the Senate, why couldn’t they just pass the organizing resolution with 50 votes and Harris? That’s how legislatures are supposed to work, right? Because McConnell could simply filibuster it. And as long as 40 other Republican senators stand by him, the Democrats can’t actually force him to hand over full control of the Senate to the party that actually won it. (Well, not without actually getting rid of the filibuster—we’ll come back to that.)

Defenders of the filibuster argue that it prevents a majority of lawmakers from ignoring the minority. They often claim it preserves the Senate’s comity and forces senators to act in a bipartisan fashion, which is supposedly good on its own merits. In functional terms, the filibuster allows a minority of senators to effectively veto what the majority of their colleagues would like to do—a bizarre inversion of how legislatures are supposed to function. In certain cases, like constitutional amendments or impeachment trials, the Senate is required to reach a two-thirds majority to act. But day-to-day business isn’t supposed to be governed by the whims of the party that didn’t win the most seats.

The history of the filibuster itself is largely ignominious. It is not part of the Founders’ vision; the Senate itself stumbled into it almost by accident. Adam Jentleson, a former Democratic Senate aide who has written about the chamber’s role in stifling democracy, noted earlier this week that the filibuster’s two greatest masters were John C. Calhoun, who used it to represent “a powerful pro-slavery minority,” and Southern senators in the early-to-mid-twentieth century, who wielded it to stifle legislation that would protect multiracial democracy. “From the end of Reconstruction until 1964, the filibuster killed only civil rights bills,” Jentleson wrote.

What’s the solution? One option would be to nix the filibuster outright. Another would be to simply render it less obstructive. “The key to reform is eliminating the minority’s ability to impose a supermajority threshold on legislation while still giving the minority a platform and making it easier for senators to bring bills and amendments up for votes,” he concluded. “For example, the Senate could require a Jimmy Stewart–style talking filibuster, not just an emailed objection, reviving debate and making the chamber a place where incentives align to produce thoughtful solutions.”

With the filibuster intact, Democrats will find it nigh impossible to pass major legislation on immigration, climate change, civil rights, and countless other issues. But more than a few institutionalist Democratic senators aren’t yet on board with scrapping the filibuster, and there would have to be unanimity among them to pull it off in a 50–50 Senate. President Joe Biden is also still opposed to abolishing the filibuster, even after McConnell’s latest stunt. “His position has not changed,” White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki told reporters on Friday.

The issue would have come up at some point during Biden’s presidency—perhaps over D.C. statehood, or a new Voting Rights Act, or some sort of pandemic relief measure. But McConnell, for some reason, has decided to force the issue now. His effort to stymie an organizing resolution shows the filibuster at its worst: an anti-democratic tool by which a handful of lawmakers can stop the majority from taking power and governing the nation. There is never a wrong time to invoke the nuclear option and get rid of the filibuster once and for all. With McConnell’s transparently self-serving demands still echoing in Congress’s recently ransacked halls, there might not be a better time finally to do it.