On Monday, two days before Donald Trump was set to exit the presidency, the White House released the names of 244 individuals who would be honored for their contributions to American society in a National Statue Garden. George Washington and Abraham Lincoln would be there, as would Martin Luther King Jr, whose birth was being honored that very day. So would Elvis Presley, Whitney Houston, Lou Gehrig, George Patton, and Frederick Douglass—who maybe is, as the president said not too long ago, “being recognized more and more.” At one point, the alphabetical list reads “Kobe Bryant, William F. Buckley, Sitting Bull.” America!

What, if anything, are we supposed to take from this vast assemblage of proper nouns, and this giant statue mosh pit that Trump has ordered to be constructed? “The chronicles of our history show that America is a land of heroes,” read a statement from the White House. “The National Garden will be built to reflect the awesome splendor of our country’s timeless exceptionalism. It will be a place where citizens, young and old, can renew their vision of greatness.” What really seems to matter, however, is that the garden will contain statues—loads and loads of statues. Conceived as a response to the pulling down of Confederate statues, it seems to be the launch of a kind of statue arms race. You want to pull down statues? Go ahead. We’ll build a whole garden full of them!

This terracotta army of random Americans will serve as an antidote to claims that this country was built on slave labor, genocide, and imperialism. “On its grounds, the devastation and discord of the moment will be overcome with abiding love of country and lasting patriotism,” the White House said. One can stop before a statue of William Howard Taft and remember that this is an exceptional country, after all. But like other Trump administration history programs, the garden is an empty, defensive gesture. No figure represents the hollowness of American exceptionalism quite like Donald Trump—which only makes it fitting that his presidency is ending with a pathetic and incoherent effort to rage against the death of American exceptionalism.

This ethos is epitomized by the other big historically themed project Trump released in the last days of his administration: the 1776 Project. Conceived as a response to The New York Times’ 1619 Project, which centered slavery in the history of America, the 1776 Project makes the case that the United States has been and always will be great. Like a “For Dummies” version of Bill O’Reilly’s historical works—you could call it “Killing American History”—the report insists, over the course of 45 shallow pages, that slavery was a necessary precondition of America, and therefore of American greatness: “As a question of practical politics, no durable union could have been formed without a compromise among the states on the issue of slavery.”

The fact that many of America’s founders were slaveholders is shrugged off—slavery, after all, existed in lots of places, not just America. The project suggests that George Washington freed all of his slaves when he died (he didn’t). It decries the civil rights movement for abandoning “the nondiscrimination and equal opportunity of colorblind civil rights in favor of ‘group rights,’” claiming that Martin Luther King Jr. would not have supported affirmative action. It is a deeply political document, somewhere between a Facebook post from your crazy uncle and the drivel on The Federalist, more concerned with pushing back against the specters of “identity politics” and “socialism” than anything that even resembles history. “It’s a hack job. It’s not a work of history,” American Historical Association executive director James Grossman told The Washington Post. “It’s a work of contentious politics designed to stoke culture wars.”

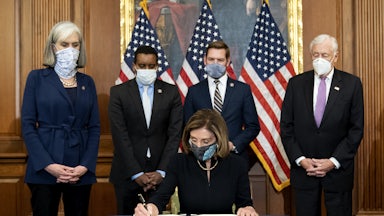

Its closest analogue is not any work of history per se, but a photo of Donald Trump hugging and kissing an American flag. As with the statue garden, what stands out is just how small the perceived slight is. In response to calls to pull down statues of people who led a rebellion against the United States, Trump has assembled a chaotic group of individuals who, together, tell no coherent counternarrative. In response to a series of essays in The New York Times, he has launched a propaganda offensive aimed at “patriotic education.”

In both cases, half-baked, regressive, and disproven arguments are made again and again. As with Trump’s presidential campaigns, these are futile attempts at unwinding huge chunks of American history, returning the country to a “simpler” time when people knew their place. It is a fitting way for Trump to end his presidency—trolling, obsessing over slights, insisting that he alone is an arbiter of greatness.

The garden and the 1776 project are best understood as a final way of owning the libs on the way out the door. And yet, they are deeply preoccupied with liberal-left criticisms of American history—they just don’t have any answers for them.