On December 12, two days before the electoral college confirmed President-elect Joe Biden’s win, Trump supporters gathered in Washington for a “Jericho March,” a prayer walk inspired by the Old Testament Israelites. To protest their supposed persecution at the hands of corrupt governmental institutions, some identified as Proud Boys stole Black Lives Matter signage from several historically Black churches, setting one banner on fire as they chanted, “Fuck antifa.”

The incident—“reminiscent of cross burnings,” in the words of the Reverend Ianther M. Mills, senior pastor of Asbury United Methodist Church, where the banner was burned—symbolizes a broader crusade that is underway against Black sacred spaces and ideologies. On November 30, six presidents of the Southern Baptist Seminary formally condemned critical race theory, which examines structural prejudice in America, as “incompatible with the Baptist Faith and Message.”

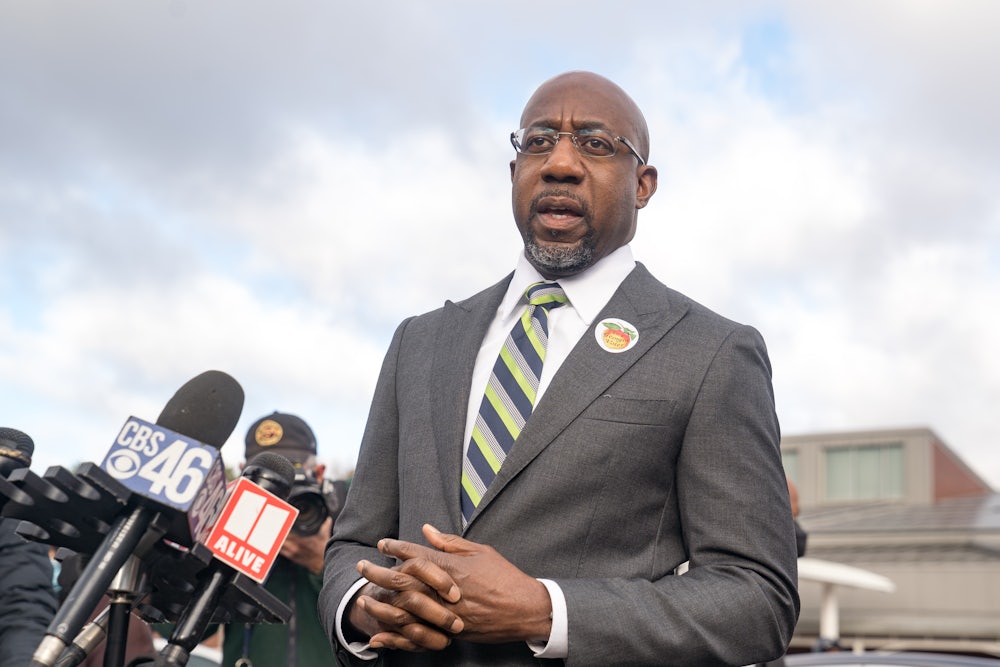

More recently, Georgia Senator Kelly Loeffler has based her reelection campaign on maligning the Black Liberation Theology that informs the ministry of her opponent, the Reverend Raphael Warnock. Loeffler would have voters believe Warnock is a “dangerous radical,” because he preaches, like the Reverend Dr. James Cone and the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. before him, that God desires the collective liberation of the oppressed and, further, that Christians have a moral responsibility to root out racism and other societal sins.

Over the weekend, Black religious leaders in Georgia shot back at Loeffler in an open letter. “We call on you to cease and desist your false characterizations of Reverend Warnock as ‘radical’ or ‘socialist,’” demanded the dozens of signatories, all Black pastors from across the state. “We see your attacks against Warnock as a broader attack against the Black Church and faith traditions for which we stand.”

With the exception of the Proud Boys, whose leaders make no bones about their belief in white supremacy, the critics who mount these attacks on Black religious traditions publicly condemn racism, choosing to frame their critique in theological terms. They say the problem with critical race theory and liberation theology is that, in addition to being divisive and reducing people to categories (oppressor/oppressed), they seek to supplant religion with secular politics. In pursuing a more just and equitable world, the proponents of such ideologies make private, individual problems (greed, racism) the purview of the law and the state, essentially erasing God from the picture. This is, to conservative critics, tantamount to idolatry.

Conservatives claim long-standing tradition for their suspicion of the political, citing scripture on the supremacy of the spiritual realm, ignoring scripture on structural sin, and generally pretending that Jesus and centuries of his followers didn’t make broad demands for a new society and instead sought merely crumbs for the poor and outcast. History, however, reveals the privatization of sin and the intense cynicism toward material politics to be relatively recent inventions, developed precisely to counter racial progress and other social reforms. It illuminates how conservatives’ individualist theology is little more than a pretext for upholding the status quo—a ruse that secular institutions have nevertheless taken seriously.

Before the Civil War, most white Christians in America prioritized social reform as a means of bringing about the thousand-year era of peace and prosperity prophesied in the New Testament. Believing Jesus would only return to earth when civilization had adequately advanced to this golden millennium, Christians crusaded for temperance, an end to poverty, and the “humane” treatment of enslaved persons, as if there were such a thing. It was only after the North forced racial equality upon the South that Southern believers became disillusioned. They decided that if slavery was a “lost cause,” then so was the notion of heaven on earth. By their reckoning, God’s ideal for human society necessitated chattel slavery, and without it, the world was doomed. The reality of injustice thus became “the unsurprising outcome of a fallen world, not a call for action,” in the words of religion scholar and author of White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity Robert P. Jones. The revamped theology, which soon worked its way to Northern states, postulated, “In due time, Christ [would] return and set things right. In the meantime … Christians should focus on spirituality and the care of souls.”

In the North, evangelists like Dwight Moody and his successor Billy Sunday appealed to the same pessimism to express alarm about waning Victorian gender norms, the rise of workers’ movements, and increasing immigration, as well as to discredit the Social Gospel movement, through which progressive Christians sought a range of social and economic reforms. These evangelists reasoned that labor strikes and governmental interventions were never going to eliminate human suffering—only God could do that. “I look on this world as a wrecked vessel,” Moody once said. “God has given me a life-boat, and said to me, ‘Moody, save as many as you can.’” Following World War I, Sunday gave such doomsday-ism a nationalist bent, describing Woodrow Wilson’s proposed League of Nations and then Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal as precursors to the end of the world and America, as people knew them.

However dejected these figures truly felt about the changes sweeping society, they did not embrace “Lost Cause” or End Times theology as a means of total surrender. Rather, they used such fatalism to shore up what was left of white power, sex-gender conventions, American exceptionalism, and unregulated capitalism. Nineteenth-century Southerners believed that, much like Jesus’s miraculous resurrection, there would come a day when the Confederacy rose again, albeit not though chattel slavery. The abandonment of earlier ideals of earthly harmony advanced this cause by undercutting any and all efforts to resist the racial injustice that remained.

Indeed, even those twentieth-century conservatives who did not regard integration as a Communist plot came to accept inequality as inevitable. Evangelist Billy Graham was one such figure, famously dismissing Dr. King’s “Dream” speech, “Only when Christ comes again will little white children of Alabama walk hand in hand with little black children.” Graham and other high-profile conservatives likewise perceived workers’ movements and the New Deal to be, at best, misguided attempts on the part of liberal Christians, which were actually going to give rise to the Antichrist (again, by marginalizing God). It was much better for Americans’ spiritual welfare if they worked long hours under unsafe conditions and let big corporations operate as they pleased.

It’s impossible to ignore the legacy of this anti-statism, not only in today’s Protestant circles but in the Catholic church, which has been significantly influenced by the post-1970s rise of evangelicalism. MAGA-oriented Catholics like Taylor Reed Marshall and Italian Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, both of whom spoke at the Jericho March, trash Pope Francis for the same reason that Southern Baptists have long disdained Black Liberation theologians: They regard social justice as a secular endeavor. According to Marshall and Viganò, the progressive pontiff’s election culminates a centuries-long effort to infiltrate the Church with communism. Francis is “hyper-focused” on uplifting the poor, dismantling institutional racism, encouraging environmental reforms, and fighting discrimination against LGBTQ persons—all priorities that distract from or directly subvert the more essential Christian missions of saving souls and surveilling people’s sex lives.

For all their phony claims, conservatives have long held an extraordinary advantage: The “nones” and the media have accepted the terrestrial-versus-celestial framing, even as they’ve tried to counter conservatives’ influence. Ever since Karl Marx called religion the opium of the people, claiming its promise of divine salvation placated the proletariat from rising up, many Communists and socialists have seized upon his utterance to claim that faith has no part in the revolution. (Marx’s critique of religion was somewhat more complicated.) In doing so, they have provided endless fodder for conservatives.

The press has played to conservatives’ hand in other ways: by describing conservatives as traditionalists or “devout” Christians; by presuming democratic politicians who discuss their faith are merely pandering; by tagging issues like abortion and gay marriage, but not immigration and health care, as religious issues; and by downplaying the religiosity of figures ranging from FDR to Dr. King. Guthrie Graves-Fitzsimmons has named the prejudice undergirding the last trend. Discussing the secularization of the civil rights icon, he writes, “Erasing King’s religiosity isn’t some kind of anomaly but part of this racist tradition of whom we label ‘religious’ today.” It may be that secular progressives also desire to redeem historical figures from what they perceive to be outmoded or backward belief systems. But it’s impossible to segment someone like King’s social and spiritual convictions, according to Graves-Fitzsimmons. The movement he led was “rooted not in some vague ‘progressive values’ or a generic equality, but in the gospel message Jesus Christ proclaimed.” And it was precisely the religious register that he and other preachers brought to civil rights that electrified the movement.

If the intensity of their attacks on people like the Reverend Warnock are any indication, conservatives take Christian progressives—and particularly Black Christian progressives—very seriously. They may soon take them even more seriously, now that many are taking formal action against institutions that refuse to meaningfully address racial inequality. On Friday, even before Black religious leaders condemned Loeffler’s tactics, 230 Baptist pastors signed a statement essentially criticizing the Southern Baptist Convention for going after the critical race theory boogeyman, while utterly ignoring the reality of systemic injustice. At least two Black pastors have announced plans to withdraw their churches from the convention.

In addition to highlighting white supremacy within their own faith communities, Black churches have long encouraged their members to know that nothing is impossible. They teach that Jesus did not limit himself to saving souls, and nor should his followers. Nonreligious liberals would be wise to recognize the radicalness of this hope and permit those like Warnock to speak in their native tongue. Reclaiming moral language in the public square may be the most effective way for progressives to resist conservatives’ deeply unbiblical privatization of sin and salvation for their own material gain.