The protagonist of Nicole Krauss’s “Switzerland,” the first short story in her new collection, To Be a Man, is a 13-year-old girl shipped by her parents to a private school in Geneva, placed under the lax supervision of a substitute English teacher, and free to spend her afternoons roaming the city on her own. Fans of Krauss’s earlier work may be disappointed to learn that this unnamed ingénue does not take advantage of her newfound freedom to seek out adventure; she does not follow a trail of clues scattered across la vieille ville to solve a far-fetched mystery; nor does she charm the gruff but tenderhearted grown-ups she befriends with her whimsical banter. Staring childlike into the window of a chocolate shop, she gets a nasty shock. “I could break you in two with one hand,” a strange man who has crept up behind her whispers calmly. She escapes unscathed, but the older teenage girls living in her boardinghouse treat her to further lessons in the hazards posed by male desire. She listens to their stories of illicit sexual encounters with rapt attention.

The author of four previous novels, Krauss has been accused of using postmodern narrative devices for sentimental purposes, of contriving extravagant story arcs that bend too pliantly toward affirmation of the essential beauty and wonder of earthly life. Her 2005 novel The History of Love, James Wood testily concluded, “is not a grown-up book for grown-up readers.” The complaint is not that she avoids serious topics: Victims and survivors of the Holocaust figure largely in the families she imagines. It’s that her treatment of her characters’ suffering is shallow; her fantastical embellishments serve to evade rather than to illuminate reality. Though she’s shed some of her youthful idealism over the years, even her recent Forest Dark (2017) reads, according to Christian Lorentzen, “like self-help,” with Franz Kafka incongruously enlisted to serve as a kind of inspirational life coach for the novel’s protagonist, a successful author named Nicole struggling to overcome writer’s block.

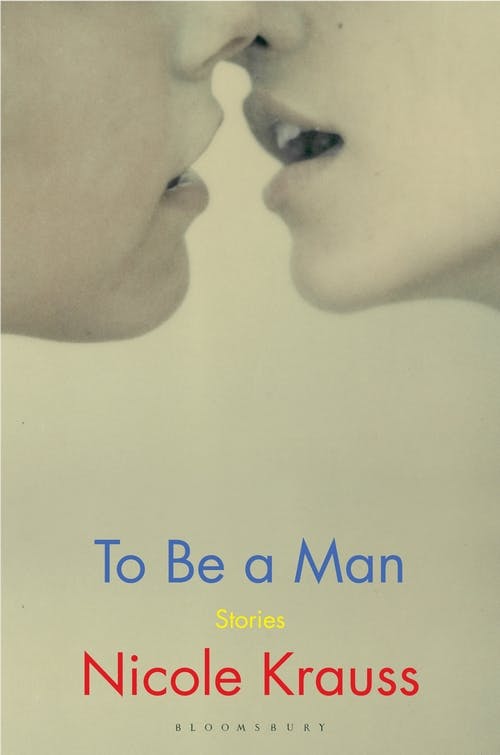

To Be a Man, a collection of short stories Krauss has published over the course of her career, features a cast of characters similar to those in her novels, most of them well-educated, cosmopolitan Jews, frequent flyers between New York City and Tel Aviv. But the tone, particularly in the more recent stories, such as “Switzerland” and “To Be a Man,” is decidedly more jaded, and the collection as a whole might be read as a rejoinder to the earlier criticisms, proof that she has put away childish things and is ready to grapple with the ugly, cruel, and irredeemable aspects of adult life. To be a man, the book suggests, is to be capable of terrifying violence. What Lorentzen describes as her “cuddly portraits of aging men” have been replaced by figures considerably more sinister.

If Krauss’s project thus far has been primarily to explore contemporary Jewish identity—a task that has led critics to compare her relentlessly and sometimes unfavorably to her (male) Jewish literary forebears, including Bernard Malamud, Isaac Bashevis Singer, and Philip Roth—in To Be a Man she nudges her long-standing preoccupations over slightly, to make room for a sustained exploration of gender roles and their destructive consequences.

In “Switzerland,” the narrator watches her teenage housemate Soraya get involved with an older wealthy European man. He pays for her visits, expects absolute compliance with his sexual demands, and eventually abuses her physically. In “I Am Asleep, but My Heart Is Awake,” a woman spends time in her deceased father’s apartment, only to have it invaded by an older man who claims to be a friend of her dad’s. Refusing to leave, he moves into the spare room and becomes a slightly dictatorial figure in her life, drawing her into a relationship that seems half-paternal, half-romantic, and wholly disturbing. In “To Be a Man,” a divorcee with two sons finds herself irresistibly attracted to a German boxer of intimidating size and strength, who grabs her throat during sex and admits that he probably would have enthusiastically killed for the Nazis had he been alive during World War II.

Perversely, it is the forceful personalities of these men, their latent or outward aggressiveness, that the women seem to find desirable. About the German boxer, the protagonist of “To Be a Man” remarks, “If someone had asked her in that moment … whether she liked being made to feel physically small next to a man, she would have had to answer yes.” In depicting these situations, Krauss is notably dispassionate, reticent to moralize about the men who force women into positions of submission. In a Guardian interview, she hints at what she hopes To Be a Man might contribute to conversations about gender relations:

I wanted to find in this book a kind of perspective on masculinity that I haven’t found in the past years in the shadow of the #MeToo movement. Trying to think about the aspects of manhood that that movement couldn’t address because it had so many other things to address. The vulnerability of men and the complexity of what is asked of them in terms of strength both by their societies and personally.

One thing her collection seems keen to emphasize is the role the women’s desires play in exposing them to the subjugating force of men, desires that would appear to render them complicit in their own victimization.

And yet the women Krauss describes are drawn into these relationships by anything other than an urge to be subordinated. Soraya puts her life at risk, the narrator conjectures, not out of a yearning to be hurt by a man, but out of a “refusal to comply with the vulnerabilities one is born into.” She is seeking to prove her strength, her imperviousness to his brutality. Repeatedly throughout the collection, women regard sexual intimacy with aggressive men as a strategy for appropriating their power; they long to get as close as they can, not because they want to be with, but because they want to be these men. The protagonist of the titular story would like her lover to believe that “whatever was explosive in him was also explosive in her.” To Be a Man: The title announces the fantasy that almost all the women in the book harbor. What might it be like to get to be so callous, so cruel, so selfish, so reckless, so unconstrained, so free? Tamar, the protagonist of “The Husband,” calls what she covets “expansiveness.” Considering a house sitter who has transitioned, she briefly imagines doing the same, “if such a thing were actually possible without extreme hardship, and every form of pain.”

This desire to assume the powers and prerogatives of masculinity also shapes the way the women in Krauss’s stories describe their relations with men. Soraya’s “coolness” in recounting her sexual liaisons, the narrator reports, suggests “a kind of unassailability.” But this is a masquerade, one that conceals hidden trauma. Krauss alerts readers not to interpret the dispassionate narrative postures she adopts as an effort to minimize the harm that men inflict or to exonerate them of guilt; rather, she is exposing the pretense of toughness that women sometimes affect as a strategy for coping with a position of structural vulnerability. If these characters seem unperturbed, even willing participants in situations that are injurious to them, it may just be a form of emotional survival, a fantasy of control, and not an expression of desire, volition, or consent.

Occasionally, Krauss reflects on the cultural pressures that force these damaging gender roles onto people. She is particularly troubled by Israeli masculinity. In “To Be a Man,” the main character’s good friend Rafi, a former member of the Israeli special forces, explains, “To become a man in his country [is] to become a soldier.” He goes on to describe the dehumanizing training he endured (being forced to run through a field of thorns, going seven days without eating or sleeping, being fed goat shit), and a mission he went on that involved almost blowing up an Arab family in an attempt to assassinate a Hezbollah leader. When does one become a man in Israel, he wonders: Is it “the first time you saw the enemy as an animal? Or the first time you treated him like one?”

Lamentably, Krauss’s critical portrayal of the Israeli state includes almost no effort to represent the Palestinians who are its primary victims. But when Palestinians do make a cameo appearance, they serve to reinforce her political critique. Visiting an Arab village, the protagonist and Rafi are chastised for “giving their dog water from a bowl that humans ate out of.” Though seemingly casual, their quibble over what is appropriate for people and what is appropriate for pets uncannily echoes Rafi’s claim about the conflation of humans and animals that life under the militarized state of Israel seems to entail—both for its male citizens and for the Palestinian people.

By the end of the story, however, Krauss relinquishes her effort to understand masculine violence as the result of circumstances or culture. Watching her sons play on the beach, among waves whose turbulence, she notes, has no clear origin, the mother considers their development into men. “When the older one worries that he is too thin and weak, I tell him how my brother had been built the same way when he was young, until—without warning, like a storm come so suddenly that someone, somewhere must have prayed for it—a change came over him.” She reflects further:

It’s like a switch, friends who have boys tell me: one day it goes on.… This worries the older one, too: the possibility that he will no longer be who he has always been, that he will lose something of his sensitivity, so valued by everyone who loves him, that he will become capable of violence.

Here the aggressive behavior of men is presented as the result not of social conditioning but of a universal drive, wired for activation in the bodies of adolescent boys, or a natural force that sweeps across them like a hurricane. This alternate account clashes with her earlier suggestion. Her identification of a different, more biological or primal culprit could, perhaps, be read as an alibi for the state of Israel, a means of mitigating or concealing its responsibility for promoting a culture of masculine violence. Or one might say she is seeking to hedge both of her accusations: Not wanting to condemn either Israel or the entire male gender, she allows each to qualify the guilt of the other.

There is still another way of understanding her equivocations. In admitting that he would have eagerly joined the Nazis during Wold War II, the main character’s German lover offers a surprising explanation. “He goes beyond the usual argument of how he would have been shaped by historical forces that would have made his participation nearly inevitable, to offer the particular vulnerabilities of his own character.” In seeking to understand mass atrocities, he suggests, historical forces, though important, are not sufficient. One also needs to think about susceptibilities. And this raises a hard question. Why are men in particular drawn to murderous enterprises? What makes them so easy to enlist in campaigns of violence? Why have they committed all but a sliver of the horrendous crimes known to the historical record? In lieu of a definitive explanation, Krauss simply registers her dismay.

Whether we blame culture, ideology, history, biology, or some toxic combination of all this, the results are enough to defeat even a sense of optimism as carefully nurtured as hers. Trying to stop the violence of men, she suggests, is like trying to stop the sea from breaking against the shore. Some readers will no doubt find this final note of fatalism disappointing—a refusal of the responsibility to take a stronger political stance. To others, Krauss’s evocation of a power so awful and ubiquitous that no act of creative magic can diminish its force will seem the very mark of her maturity.