Last February, I had the honor of being publicly snubbed by Jay Rayner, the fiery restaurant critic for The Guardian, who dismissed my essay about the “crisis” of the American restaurant review as “staggeringly parochial.” Apparently, my essay did not say enough about the British restaurant review. Rayner sketched a broad distinction between the somber American critic driven by “civic duty” with a “respectful and solicitous” tone (not adjectives commonly associated with the Stars and Stripes) and the Brits, who are the “writerly equivalent of bare-knuckle fighters.” While tame Americans write descriptions such as “creamy slips of uni” or “a fragrant lake of oil,” the English understand the simple joy of comparing a rude waitstaff to an “unlubricated colonoscopy.” Rayner ended his column with an appeal to un-seriousness: “Learn to relax a little. After all, we’re not war reporters. We’re only writing about lunch.”

Then the pandemic hit. As restaurants across the world were forced to close, the value of Rayner’s style of blitzkrieg criticism became a fraught question. While American reviewers reacted to the shutdown with broader assessments of the state of the restaurant industry and its future, the major British critics spent the lockdown taking “trips down Memory Lane” and “becoming emotionally attached to frying pans.” Then in June, Rayner declared an indefinite hiatus from negative reviews, announcing, “If I can’t be broadly positive I simply won’t be writing anything,” even though the shift “risks making me less readable.”

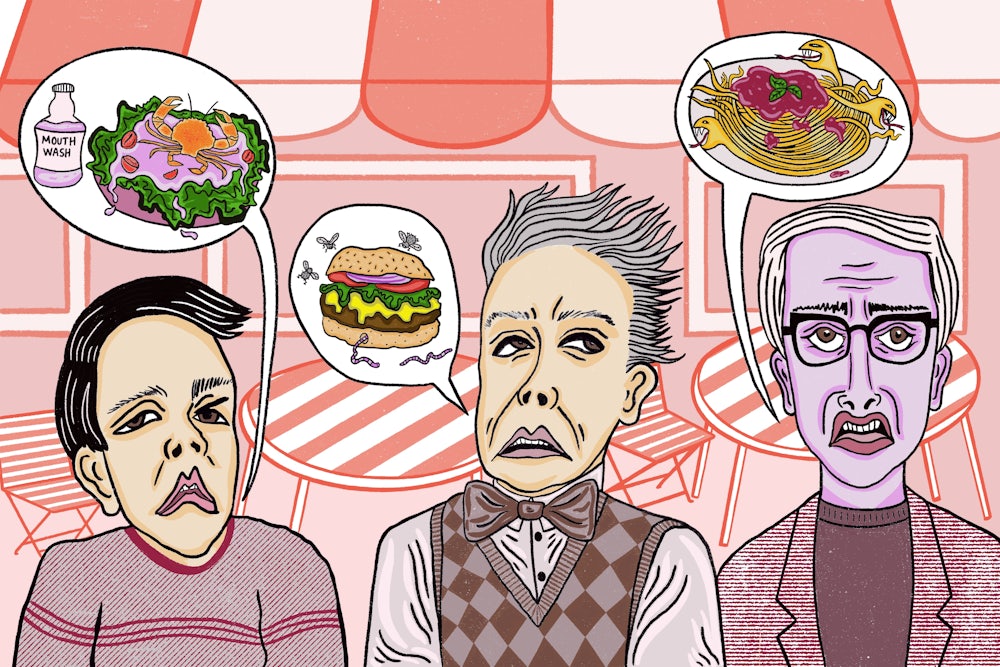

Here, Rayner echoes the universal dogma of restaurant criticism that bad food makes for better copy than good. As Eater expounds, “It’s those baffling, disappointing, and downright bad meals that often make for the most entertaining reads.” “I never send stuff back,” confesses Sam Sifton of The New York Times, “because there could be the delicious possibility of awfulness at the end of the dish that could make for great prose.” In fact, it is fair to say that the smackdown review may be the single most venerated literary genre in all of food journalism. Every December, Eater gleefully catalogs the year’s “most scathing restaurant reviews,” enshrining the savage one-liners that show critics going “for the kill.” Roast chicken lived in a greasy no-man’s land—and no man I know would love it. Overwhelming notes of Robitussin and rubbing alcohol. Risotto with scallops is where hope goes to die. But there are no articles commemorating the year’s most scintillating culinary compliments. Why? Because entertainment comes from cruelty.

These gladiatorial takedowns are not really excellent writing about food—but rather about pain. Cuisine is merely the vessel of vitriol, the muse of literary malice. In this confusion between entertaining prose and good criticism, we find the germ of a larger malady that afflicts restaurant reviews. Conflating insult comedy with serious critique incubates a set of unhealthy rhetorical habits that powerfully distort how reviewers write and think about food. This swashbuckling literary style subconsciously shapes—and limits—the profession’s conception of quality criticism.

For instance, many British

reviewers seem uncertain if high-caliber prose is even possible in the

compliments-only era of Covid-19. Telegraph

reviewer William Sitwell proclaimed

the “sharp pen of the critic will return when the good times return.” Rayner

began a

recent column by listing the “writing opportunities missed” during the

lockdown: the “clumsily made sauces” not compared to “bodily fluids” in “need

of antibiotics” and the abandoned arson jokes about décor “crying out” for a

“can of petrol.” To ask the obvious question: How did comparing clumsy

sauces to urinary diseases become the apex of “good” restaurant writing?

This pledge of blanket positivity comes at a moment of unprecedented hardship and uncertainty for the restaurant industry. Now is not the time for phony optimism or mandatory applause but righteous rage and indignation—yet redirected from problems in table décor toward problems in kitchen culture. Contemporary dining teems with contentious issues crying out for serious discussion: widespread unemployment among food workers, sexual misconduct allegations in top kitchens, hazardous labor laws, a lack of diversity in food media, record food insecurity in the U.K. and the U.S., to name a few. Any of these questions would benefit from a critic’s incisive intellect and informed reporting. Yet traditional reviewers remain trapped in the simplistic binary of barbaric putdowns or mindless praise.

This paralysis is a symptom of a larger generational debate over the proper role of the food critic. In the classical view, the reviewer is a gastronomic evaluator whose judgments exist outside any social context. For younger generations, the food critic is closer to a gastronomic ecologist responsible for exploring patterns of meaning in eating culture at large. The classical tradition draws a hard red line between plate and politics that prohibits the critic’s mind from leaving the dining room, but the pandemic is just one reason among many that the old divide between the food critic and the food journalist has started to blur.

In the middle of a historic crisis, it is time to reassess food criticism’s dominant, machismo style that teaches reviewers to write sharply on minor culinary mistakes but blunt their pen when confronted with sweeping problems. Moreover, by studying how the pugilist style works, I believe we can diagnose what ails the larger tradition of food writing in the Anglosphere. To make this diagnosis, I read hundreds of negative restaurant reviews across two decades, including every piece mentioned in an Eater annual list since 2011. Overall, I compiled a 6,000-word compendium of critical insults from dozens of reviewers. Every quote cited below comes from a real review and critic. What I found is a prose pathology whose manic habits infiltrate and sabotage the public perception and social analysis of food in many subversive ways.

The data suggests that most restaurant critics suffer from a severe case of chronic prose inflation. This condition afflicts authors with an impulse to overstate and overdescribe, to enlarge each opinion or emotion. At the sentence level, the critic writes for the pull quote: “One of the worst things anyone can eat outside of Rikers.” “The Potemkin Village of lasagnas.” “A crab restaurant for recently married couples who hope they’ll get divorced.” But no good essay is made of pull quotes alone. And the cumulative impact of constantly writing for the provocative headline rather than the intelligent reader is a tendency among critics to raise their rhetorical volume out of habit rather than necessity.

In unfavorable reviews, culinary

diction escalates into a form of operatic invective. “Dry” turns to “dusty” or

“desiccated.” “Oily” balloons to “oleaginous.” “Sour” curdles to

“mouth-puckering.” Why simply call a soup “bitter” when you can hit a harsher

note with “acrid” or “astringent”? Some takedown reviews read like a

vindictive thesaurus entry: “brown

mucoid gloop”; “congealed,

gelatinous cubes”; “sodden,

sad sinkholes with a potato-like appearance.” Mistaking severity for honesty, critics pile on

extra syllables and superlatives to embellish their abuse. “Cooking

so cack-handed, so foul, so astoundingly

grim” (emphasis mine); “the rubberiest,

chewiest, saddest excuse for a crustacean.” Metaphysical adverbs

rain down to turn banal entrées into philosophical offenses: Dishes are “mysteriously bland” or “unfathomably dry,” as if the meat’s lack of

moisture transcends the bounds of human comprehension.

Word choice becomes a literary blood sport. A frenzied instinct pushes the author to reach for the overaggressive image: a “wrist-slashingly ghastly” meal, “teeth-curlingly sweet” onions, a “condiment full of machismo and casual violence.” Critics pilfer the natural sciences for fresh terms to decorate their disdain and raid organic chemistry as a gold mine of nauseating verbiage: A steak tartare tingles with “a fetid, ammonia-like tang”; a cocktail resembles “norovirus in a glass”; and a beet salad stings as if “refrigerated next to an uncovered vat of liquid aspirin.” Disease offers another arsenal of rhetorical ammunition (purulent, pustular), while A.A. Gill’s old columns read like a refresher course in urinary-digestive disorders, as one encounters a “vaguely proctological” stove, a “suppurating, renal brick” of veal, and “labially pink” linen that exudes “a colonic appeal.”

The closest parallel for the restaurant critic’s mentality is the insult comic. Negative reviews often read like a standup act, with dozens of disconnected puns and laugh lines that entertain for the moment but rarely culminate in a larger argument. Even the basic structure of many sentences follows the grammar of a joke: a setup and a punch line. “Biting into the dish doesn’t so much evoke opening a gift,” Ryan Sutton drawls, “as it does finding coal in one’s stocking.” “If Villard Michel Richard doesn’t make it as a restaurant,” Pete Wells puns, “it could reopen as the Museum of Unappetizing Brown Sauces.” Decent lines, but there are no insights here, just overseasoned insults. Too often, these gotcha gags replace actual analysis of the flaws of the food, and one suspects that critics are crafting their prose to land laughs rather than ideas.

This malicious verbal inflation accelerates from a mild disorder into a raging mania when you move into metaphors. Images of mangled corpses, natural disasters, oozing sores, and lurid felonies flood the pages of negative restaurant reviews. “The crime that comes to mind first when I think of the Ciprianis,” Frank Bruni writes, “is highway robbery.” For Tina Nguyen, a poorly plated steak slumps “like a dead body inside a T-boned minivan.” For Jeff Ruby, fried chicken left “a greasy feeling” that, “like the demonic clown from It, could not be destroyed.” In the New York Post, Steve Cuozzo meets a fall vegetable soup that evokes a “famine zone where ingredients are stretched,” and in The New York Times, William Grimes stumbles on a tyrannical tomato that “imposed totalitarian rule over a cowed population of clams, mussels, and squid.” One encounters a “funeral pyre of French fries,” a chocolate tuille flapping “like something that’s fallen off a burns victim,” and kidneys that “could be the result of an accident involving rat babies in a nuclear reactor.” Not to be outdone, Matthew Norman deems one bistro’s secret sauce “a mustard-based crime against humanity.”

Why write this way? Why compare tomato soup to totalitarian dictators? It’s fun. And it’s easy. There are no real stakes for describing bad food. For these pugilist reviewers, the worst outcome is a bored reader, and thus the sheer unimportance of the subject sanctions a degree of exuberant cruelty unmatched in any other branch of criticism. That’s why the scorched-earth style perfected by columnists like Jay Rayner is so wildly entertaining: Negative reviews have the poetic license to pepper their prose with nuclear meltdowns and enlist figures from Mussolini to Marquis de Sade to guest star in any given sentence. Yet when a critic compares a sauce to a crime against humanity, it tells you something important. One senses the writer does not care about the food or even the crime, because it functions as a fill-in-the-blanks tragedy commandeered from the annals of human suffering to spice up a second-rate line of prose. Both items in the analogy—the real food and the imagined atrocity—just become props in the critic’s sideshow act for the reader’s vicarious entertainment.

In other words, mockery is the mission. Comedy outweighs insight as the primary ambition of these analogies. And this type of mock simile—comparing small culinary errors to eye-catching calamities—has become the restaurant review’s definitive literary device. Consider this short list of the misfortunes encountered through simile by the masters of the form, Jay Rayner and A.A. Gill:

- like King Midas has suffered psoriasis over your dinner

- like something that has spent its life chained to a radiator in the basement

- treated you like social scurvy with contagious halitosis

- smeared like a nappy accident around a pottery bowel—sorry, that should be bowl

- tasted as if your mouth had been used as the swab bin in an animal hospital

- like eating a condom that’s been left lying about in a dusty greengrocer’s

What, exactly, is the point of these similes? While a traditional simile highlights an unexpected connection between two items, the mock simile overpowers the object being described with the nuclear malevolence of its counterpart. When the goal is not imparting insight but amplifying malice, any rhetorical escalation is allowed.

Promiscuous hyperbole has consequences beyond provocation and imprecision. At the literary level, these grotesque metaphors and overcaffeinated insults are the linguistic equivalent of junk food. While there’s nothing wrong with a little bathroom humor in moderation, a steady diet of car-bomb and condom similes will ruin any author’s expressive palette. Left unchecked, food critics often develop an unhealthy craving for offensive, high-conflict imagery and start to seek out extreme comparisons over more balanced options. For instance, you find Rayner describing a mussel that “looks like the retracted scrotum of a hairless cat,” a croquette “the size and color of a cat’s turd,” and a puree that makes him wince “like a cat’s arse that’s brushed against nettles.” After getting hooked on such Red Bull rhetoric, reviewers gradually spoil their taste for subtler flavors of thought and feeling.

There is also a second consequence to such hyperbolic prose. I worry this junk-food style not only warps the critic’s relation to language but to society as well. Mock similes devolve from a literary to a moral hazard when issues such as epidemics, bankruptcy, and sexual abuse have become mainstream concerns in the restaurant world. Once a critic has compared a chocolate ganache to “the Rohypnol of desserts” (the brand name for a roofie), it is difficult to turn around and write intelligently about chefs facing real rape allegations. After habitually using grievous tragedies as the punch line for jokes, many critics struggle to find a literary voice that can analyze these same problems as complex social issues. It’s always easier to say: Not my job.

Now in the midst of the pandemic, an economic crisis that has decimated the restaurant industry, renewed calls for racial justice, and a wave of sexual assault allegations against top chefs, restaurants stand in the crossroads of contemporary moral, political, and economic dilemmas. Yet the consensus response among British reviewers is to meet the crisis with banal culinary compliments—imploring restaurant critics to put down their hatchets and “accentuate the positives” since, in Rayner’s words, to “kick anyone in this business at the moment would be the act of an arsehole.”

This is the heart of the case against bare-knuckle criticism: The problem is not the presence of negativity but the object of that negativity. The insult-comic style trains critics to channel their scorn toward minor errors rather than major iniquities, breeding a bipolar prose that lambasts rude hosts and greasy sauces with apocalyptic intensity yet says little to nothing about rapist chefs and unfair labor laws. In other words, pugilist prose offers an idiom of flamboyant irrelevance. This is a voice with strong words for small matters but polite silence for serious concerns—a voice that will not speak truth to power but only to cauliflower.

In this context, the British critic’s vow to accentuate the positive is not a sign of taking responsibility but of shirking it, a refusal to address the real problems in the restaurant industry. Restaurant critics are the appointed arbiters of eating culture, leading public opinion on the key dining questions of the day, and pledging to “sheath” their pens until the “good times return” is akin to a general who will only step onto the battlefield during peacetime. Finding clever ways to insult soggy vegetables has never been a full realization of a critic’s talent and intelligence—and right now, the food world needs that intelligence and experience more than ever.

I want to offer one final analogy to explain how the extremities of pugilist prose deform the critical imagination. This example comes courtesy of William Sitwell. “It is appropriate,” Sitwell declared on BBC’s Newsnight at the start of the shutdown, “that we [critics] don’t sharpen our pen and use them as knives and twist them into chefs and restaurateurs, because the hospitality industry is on its knees.” What’s revealing about this quote is the instinct to view a knife as a weapon and not a tool. Despite the fact that blades are a key instrument in cooking, medicine, woodwork, and countless other activities, Sitwell only sees a means for violence. Think about Sitwell’s image: the bloodied restaurant industry on its knees as the critic brandishes a knife deciding between mercy and mutilation. This brutal simplification—picturing the sharp-minded reviewer not as a craftsman or surgeon but a murderer—is the ultimate outcome of long-term exposure to insult criticism.

Sitwell’s analogy offers a parable of missed potential: The critic holds an instrument of healing in his hand but only perceives its power for pain. The trouble is not the critic’s tool but the critic’s attitude. We must reclaim healthy negativity as a tool of incisive awareness and teach restaurant critics to wield their intellect like a scalpel rather than a cudgel. Because if medicine was the guiding metaphor for restaurant reviews, rather than murder, critics might begin to approach the dining industry less as a victim deserving pity than a patient deserving treatment. And when a patient in critical condition seeks surgery, no responsible doctor would sheath their scalpel and call it charity.