For enslaved Black Americans contemplating escape before the Civil War, the North increasingly looked like a bad option. Though Northern states had abolished slavery by the early nineteenth century, free Blacks were denied the right to vote, had limited employment options, and endured legal segregation. Much of the Midwest restricted free Blacks from even entering. There were also two threats that, until recently, have received insufficient attention: the kidnapping of free and fugitive Blacks in numbers that may be equal to those who escaped on the Underground Railroad and the fact that major “free” cities like New York had become bastions of proslavery support. Because Manhattan’s financial sector had become dependent on slave-grown cotton, New York officials ignored or abetted the illegal slave ships leaving its ports and the Black New Yorkers being snatched from the city’s streets. When Alabama’s governor wrote to his New York counterpart, William Marcy, in 1835, asking for help retrieving runaways, Marcy assured him that “the people of New York generally entertain the most friendly sentiments toward their brethren in the South,” adding: “They know their duties to you and will respect them.”

Not surprisingly, in 1831, Honorine, an enslaved woman in Louisiana, chose to run south instead—to Mexico. Like as many as 5,000 other enslaved Black Americans who escaped to Mexico, Honorine knew of the nation’s reputation as a safe haven for fugitive slaves. Nearly half of Mexico’s states had enacted emancipation laws by 1827, and 10 years later, its federal government abolished slavery altogether, nearly three decades before the United States. Though American slaveholders pursued their runaways in Mexico as aggressively as they did in New York, Mexican officials were far more firm in refusing to turn them over. In 1850, Mexico’s diplomat in Washington, D.C., rebuffed demands from the State Department to extradite fugitives, citing a law Mexico had passed the previous year guaranteeing freedom to all slaves who made it to Mexican soil. Before that point, only Haiti, the Western hemisphere’s first Black republic, had such a radical and—to a slaveholding nation like the U.S.—potentially destabilizing law on its books.

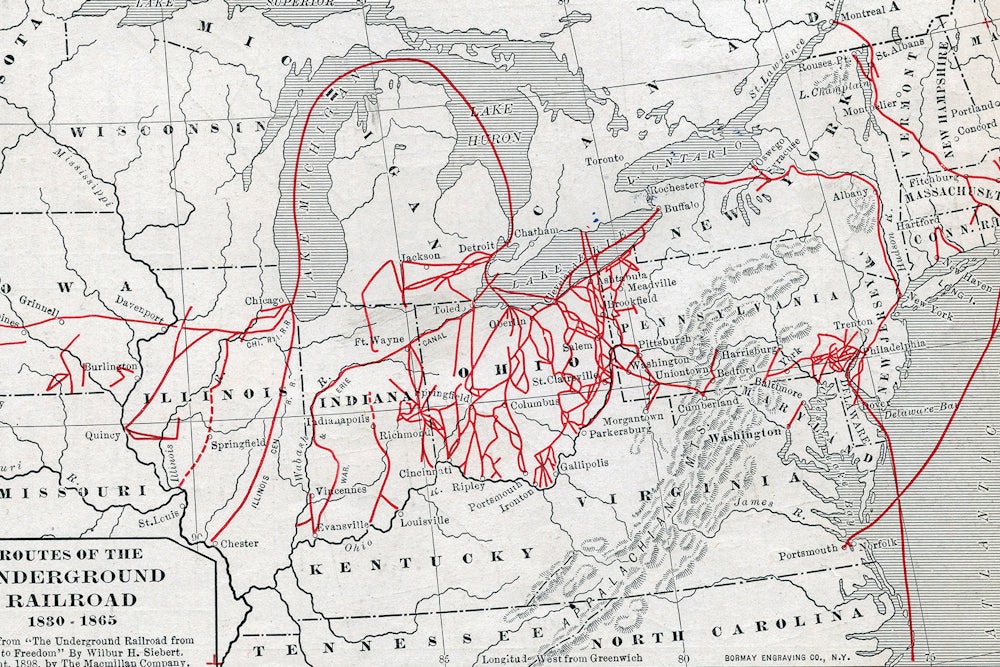

That Mexico might have been freer than the “free” North will come as a surprise to many readers. The national narrative we have about slavery and racism remains woefully provincial. Slavery was America’s “original sin,” we tell ourselves—obscuring the fact that slavery existed in nearly all of Europe’s New World colonies and was abolished by all nations, except Cuba and Brazil, decades before the U.S. Our national narrative is also conveniently sectional, positioning a bad, racist South against a good, anti-slavery North. But a spate of new books suggests that we might need to redraw our mental maps. The real firewall between slavery and freedom was not the line that cut through the U.S., separating North from South, but perhaps the one that cut beneath it, along the Mexican border.

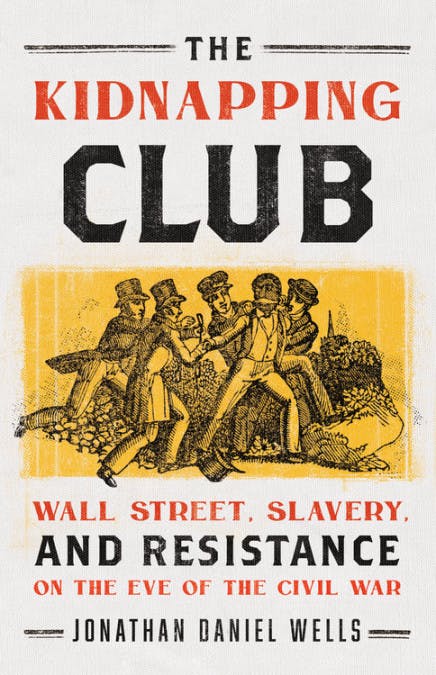

In The Kidnapping Club, the historian Jonathan Daniel Wells focuses on the hundreds of kidnappings that New York’s Black community experienced in the three decades before the Civil War, with an additional few chapters on Manhattan’s role in the illegal transatlantic slave trade. Both slave trades persisted, Wells writes, because of Manhattan’s financial ties to slaveholders. Building on the resurgent literature on slavery and capitalism, Wells deftly captures the ways Manhattan’s financial elite, such as Moses Taylor—head of what became today’s Citibank—advocated for slaveholders’ interests. When Congress passed the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, strengthening slaveholders’ constitutional right to retrieve runaways in free states, Taylor helped form an influential advocacy group, the Union Safety Committee, comprised of the city’s most prominent proslavery Democrats and businessmen. The group publicly chastised “northern fanaticism”—meaning Black and white abolitionists—for challenging “the Constitutional rights of the South,” knowing full well that, as Wells writes, “the city’s prosperity was at stake.”

Even before the Fugitive Slave Law, Black New Yorkers were being picked off the streets and sold to the South with impunity. Wells focuses much of his story on Manhattan’s criminal justice system: the police officers who captured runaways on behalf of Southern slaveholders, and powerful officials, like the city recorder Richard Riker and Governor William Marcy, who gave New York’s police officers legal authority to capture runaways. The problem was that legally free Black New Yorkers were just as likely to be captured as runaways, and distinguishing between the two was near-impossible. Moreover, captured Black New Yorkers were not guaranteed a trial by jury: It was up to people like Riker to decide.

That left men like Martin Parmer easy prey. Parmer was in fact a fugitive from Virginia, but when New York policemen captured him in 1834 on behalf of his owner, pocketing the handsome reward, his owner had so little knowledge of Parmer that Riker postponed Parmer’s trial while he looked for whites to testify that Parmer was a former slave. As Parmer sat in jail, waiting, 11 other Black men accused of being runways sat nearby, all captured by New York’s police. Wells shows that several of these men were legally free, but nearly all were bound for slavery “by a court system that cared little whether they had been born free or enslaved.”

The Black community put up the best defense it could. The Kidnapping Club’s other main focus is New York’s Black activist community. Wells highlights David Ruggles, a freeborn Black New Yorker, who formed a vital organization—the New York Vigilance Committee—to protect fugitives and free Blacks from enslavement. The organization, founded in 1835, relied on funds from the local Black community and wealthy white New Yorkers, such as Lewis Tappan, to provide legal defense, food, and shelter for kidnapped Blacks and fugitives, and it was Ruggles’s magazine, Mirror of Liberty, that brought to light many of the kidnappings recounted in Wells’s book.

The Kidnapping Club is meant to read as parable for today, but Wells’s eagerness to tell a dark but inspiring story—of how radical Black activists and their white allies challenged a broken criminal justice and capitalist system—at times leads him to elide significant historical details. For instance, when explaining why New York’s financial community rushed to support Lincoln’s war effort after years as slaveholders’ lapdogs, he suggests that their about-face was driven by a “powerful sense of duty.” But another interpretation is that bankers like Moses Taylor understood that they needed the South to stay in the Union. As Sven Beckert has argued, the problem for Wall Street wasn’t slavery: It was secession. Without the South in the Union, the costs of doing business with cotton planters would have been too high.

One senses that, here and elsewhere, Wells’s desire to offer his readers glimmers of hope—that greed can be sublimated to a larger sense of justice—works against what might be a more useful historical lesson: What matters is less what people think than what they do. No one knew this better than Black abolitionists. Radical abolitionists like Frederick Douglass, himself a fugitive slave aided by Ruggles, was less concerned with the racial views of Lincoln than with his politics. Despite Lincoln’s political moderation and racism, he was the anti-slavery president, and through him, Black and white abolitionists were able to push through remarkable, if fleeting, change.

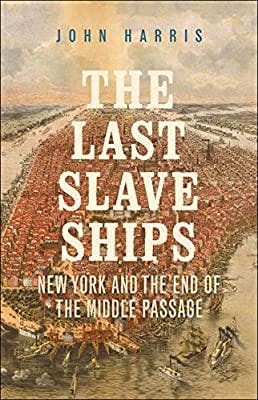

Whereas Wells focuses mostly on what the historian Richard Bell has dubbed the Reverse Underground Railroad, John Harris’s The Last Slave Ships zeroes in on Manhattan’s role in the illegal transatlantic slave trade. Though the U.S. and Britain abolished the transatlantic slave trade in 1808, U.S. enforcement was so lax that, between 1850 and 1867, around 200,000 enslaved Africans were smuggled into Cuba and Brazil—where slavery remained legal until the 1880s—on slave ships operated by Manhattan-based traffickers. Like the kidnapping of Black New Yorkers, this story is not unknown, but Harris offers the first comprehensive study of its size and extent, and of the specific political dynamics that turned New York into “one of the trade’s last Atlantic hubs.” It is a remarkable piece of scholarship, sophisticated yet crisply written, and deserves the widest possible audience.

Manhattan emerged as a central port for this illegal slave trade in part for the reason Wells identifies: New York’s business and shipping communities did lucrative trade with slaveholding Brazilian coffee and Cuban sugar producers. But there were factors beyond commerce, too. Brazil banned its transatlantic slave trade in 1836, but it did not aggressively enforce the ban until 1852, after a series of slave revolts and aggressive pressure from the British. In the wake of Brazil’s crackdown, prominent Brazilian slave traders, like Manoel Cunha Reis, moved to New York City, where they had long-standing relationships with Manhattan shipbuilders, suppliers, and merchants. Reis and his accomplices, known as the Portuguese Company (also featured in Wells’s book), were also confident that neither New York nor federal officials, overwhelmingly proslavery Democrats, would enforce the U.S. ban. Though the city’s proslavery newspapers expressed outrage at the occasional discovery of illegal slave ships in Manhattan’s harbors, Harris argues they only did this because it allowed Democrats to make a case for seizing Cuba for the U.S., a key objective of expansionist Southern slaveholders in the 1850s. By blaming Cuba for not enforcing its own slave trade ban, slavery’s defenders had their justification for war.

Another reason New York emerged as a hub was because the federal government, keen on asserting national independence, refused to allow British naval ships to stop and search American vessels. Brazilian and Cuban traffickers purchased the U.S. flag for their ships using New York accomplices as “straw buyers”; Harris finds that 75 percent of the 474 illegal slaving ships between 1853 and 1866 flew an American flag. In what is perhaps his best chapter, he painstakingly analyzes how conditions on board slave ships changed as the trade became illegal. Slave ships became more tightly packed, routinely carrying more than 600 Africans, “almost double the average for the trade during its entire life span.” By the 1850s, males made up 80 percent of captives, compared to two-thirds over the course of the Atlantic slave trade’s 350-year history. After 1850, children comprised half of all captives, nearly twice the overall average. As the amount of food and space shrank for each captive, the death rate spiked, increasing by five percentage points at midcentury to 17 percent. If there was any relief, Harris notes, it came in the “grim reality” of more deaths, the dead bodies tossed overboard providing more room for the living.

Instead of focusing on the street-level activism of men like Ruggles, Harris trains his eye on federal policy. In 1861, shortly after the South seceded, Lincoln created a new federal unit, called the Suppression of the African Slave Trade, to aggressively prosecute American slave traders. New York officials took the hint, immediately cracking down on local traffickers. Famously, when in 1862 one such trafficker—Nathaniel Gordon Jr.—was charged under an 1820 law making involvement in the trade punishable by death, Lincoln refused to commute his sentence. The execution of Gordon was a national sensation, cheered in Harper’s and The New York Times and denounced by their proslavery counterparts.

But what finally caused the number of illegal slave ships in New York to plummet was the treaty Lincoln’s secretary of state, William Seward, signed with his British counterpart in April 1862. The Lyons-Seward Treaty allowed British naval ships to search American flag–flying vessels near Africa’s coast and promised to prosecute illegal traffickers in the U.S. Harris notes that the treaty was driven as much by realpolitik as anything else—Lincoln needed to entice the British away from recognizing the Confederacy. But it worked: Within months, enslavers like the Portuguese Company vanished.

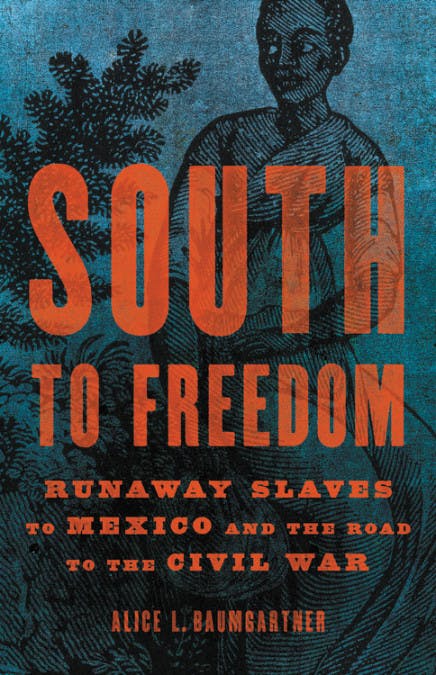

Given the precarity of freedom in the antebellum North, enslaved Black Americans often sought freedom in Mexico instead. Scholars of the Underground Railroad have long known that a small stream of runaways escaped to Mexico, but Alice Baumgartner’s South to Freedom: Runaway Slaves to Mexico and the Road to the Civil War offers its first full accounting. Having immersed herself in Mexican archives, Baumgartner cautiously suggests that 3,000 to 5,000 slaves fled to Mexico before the Civil War. This might seem slight in comparison to the 30,000 to 100,000 slaves who escaped to the North or Canada, but the difference can largely be explained by geography and timing. Mexico did not gain independence until 1821, and its national emancipation law went into effect 16 years later. Even more important, only slaves that lived near free states, whether Northern ones or Mexico, were likely to abscond. Not surprisingly, the majority of slaves to escape to free Northern states, like Pennsylvania or Ohio, lived in slave states that bordered them; similarly, the vast majority of fugitives to Mexico lived in Texas, which did not join the Union until 1845.

South to Freedom does far more than establish numbers. It is primarily concerned with understanding why the U.S. failed to stop slavery’s expansion, why Mexico did, and using that knowledge to cast the coming of the Civil War in a new light. Baumgartner argues that Mexico’s anti-slavery policies led the South to try to conquer the nation, partly achieving that goal through the U.S.-Mexican War, which lasted from 1846 to 1848. But the South miscalculated. It hoped to reestablish slavery in the territory it acquired from Mexico after the war (what became California, Utah, and the Southwest) but instead fueled an anti-slavery backlash. The Republican Party, established in 1854, refused to allow slavery to expand into Western territories, especially where it had already been abolished—including those seized from Mexico. In this way, Lincoln’s anti-slavery Republican Party, and the abolitionist war it ultimately fought, was partly an outgrowth of Mexican emancipation policies enacted decades earlier.

Baumgartner has achieved a rare thing: She has made an important academic contribution, while also writing in beautiful, accessible prose. South to Freedom shows that U.S. officials proved far less willing to overcome slaveholder pressure than Mexican authorities were. From the 1803 Louisiana Purchase until Lincoln’s election, U.S. politicians repeatedly backed down to planters who insisted that slavery be allowed to expand into federal territories, fearing that if they challenged slaveholders, they might cause the Union to disintegrate. By contrast, Mexican officials feared that if they did not restrict slavery, more slaveholders would enter, destroying their fragile republic. This nearly happened when Stephen A. Austin, a Louisiana slaveholder, moved to the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas in 1821. Prioritizing the need for settlers over the potential for instability, Mexican officials allowed Austin to enter with his slaves. But to Austin’s chagrin, his state legislature enacted a gradual emancipation law in 1827, joining eight other Mexican states. That Austin led a rebellion eight years later, establishing the Republic of Texas, was a surprise to no one.

After Texas seceded, Mexico abolished slavery nationwide in 1837. Yet Mexico’s emancipation laws were hardly based on a “principled defense of liberty,” Baumgartner writes. Like scholars of emancipation elsewhere in the Western hemisphere, she argues that Mexican abolition served pressing political needs. Its 1837 emancipation law was, among other things, “a calculated attempt to undermine the rebellion of Texas.” Similarly, its 1849 free soil law, which freed any slave who made it to Mexican soil, was intended to destabilize the U.S. Echoing what the historian Christopher L. Brown has called “moral capital,” Baumgartner ultimately contends that abolishing slavery allowed Mexico to assume “the mantle of high righteousness,” gaining powerful political allies in the process.

Life for fugitive Blacks in Mexico was hardly idyllic. In exchange for citizenship, many joined the military but had to fight wars against “barbarous” Native Americans, as Mexican officials called them. Others found work as day laborers or hacienda servants, yet because corporal punishment was legal and labor contracts often exploitative, “coercion continued in other forms,” Baumgartner writes.

Nonetheless, many fugitives found life more tolerable in Mexico than in the U.S. Mexico placed no racial barrier to citizenship, and its new 1857 constitution eased the pathway to citizenship for fugitive slaves. That the U.S. denied Black Americans citizenship that same year, with Roger B. Taney’s 1857 Dred Scott decision, is an irony lost neither on Baumgartner nor on Americans at the time. The anti-slavery New-York Tribune crowed that Mexico had “repudiated the Taney interpretation of the rights of man,” reveling in the fact that Mexico, long ridiculed as America’s less civilized neighbor, now had a constitution more liberal than its own.

Although Americans in the past—whether enslaved Blacks, slavery’s defenders, or their antagonists—were certainly aware of Mexico’s more liberal emancipation laws, history has largely ignored them. Baumgartner largely attributes this lacuna to a combination of jingoism and racism, a reflexive disbelief that an “uncivilized heterogenous people,” as one nineteenth-century U.S. observer put it, could possibly be freer than America itself. But she also ascribes it to a certain kind of academic cynicism. In recent decades, historians have challenged triumphalist narratives of emancipation, in Mexico and elsewhere, which so often license other forms of discrimination. Mexican histories of emancipation have, for instance, made it easy to overlook the exploitation of Black and Indigenous people that continued after abolition, as have similar histories in the U.S.

To downplay those realities, Baumgartner agrees, is a gross abuse of history. “But to make them the entire story,” she adds, “results in a different kind of distortion. Even hypocritical, self-interested, or unenforced policies could have profound significance. These unexpected consequences should not be ignored because they arose amid unfilled promises.” Put another way, acknowledging that change happens because of impure motives should not blind us to what that change meant to those who benefited from it. Nor should it deflect our attention from what remains unfinished. More broadly, emancipation’s late arrival in the U.S., coupled with freedom’s precarity nationwide, ought to challenge our penchant for exceptionalism. Just as slavery was not unique to American history, neither was freedom. We might still have something to learn from other nations for whom freedom was not just an aspiration but something closer to a reality.