The debate over how to characterize what the country’s been put through over the past three weeks will carry on for the rest of our lives. And Donald Trump’s waddle through the stages of grief is sure to last through January. But his election gambit is functionally over. Results have been certified in Georgia, Michigan, and Pennsylvania; the General Services Administration has formally recognized Joe Biden as president-elect; and the transition team finally has a shiny, new dot-gov email address that means more, materially speaking, than any concession speech.

Even in the conservative press, prominent figures have thrown in the towel. On Monday night, Fox News’s Laura Ingraham told her viewers that Biden will be inaugurated in January, “unless the legal situation changes in a dramatic and unlikely manner.” Earlier that day, Rush Limbaugh castigated Trump’s legal team for last week’s bizarre press conference. “You call a gigantic press conference like that—one that lasts an hour—and you announce massive bombshells, then you better have some bombshells,” he said. “There better be something at that press conference other than what we got, such as a hacker who can tell us, ‘Yep, everything these guys have said is true. I’ve looked into it. I’ve run the software, I’ve hacked this, I’ve hacked that.’ Even put him behind a screen, if you want to protect his identity.”

The efforts now in conservative media to talk the base back down to reality are only coming after weeks of rhetoric aimed at shooting imaginations into high orbit in the first place—rhetoric a number of prominent Republicans, including Senator Ted Cruz and House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, actively indulged in. And while a few Trump critics have piped up, most other Republicans in Congress have either tersely endorsed Trump’s complaints or kept mum about them, as Hawaii Senator Brian Schatz said last week. “Republican Senators are awfully quiet during this ongoing tinpot dictator act but they still think they deserve to run the Senate,” he tweeted. “If this were happening in Central America all of these silent Senators would be proposing sanctions.”

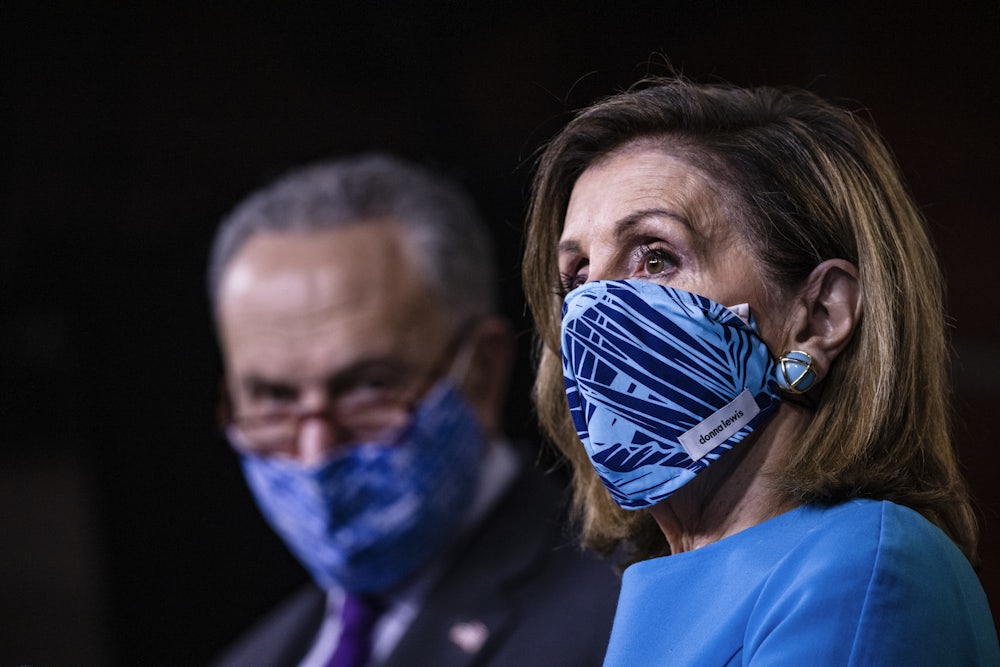

But in truth, Republican senators aren’t the only ones who’ve been awfully quiet about all that’s been going on. Where have the Democrats been? Biden has been talking about the transition at every turn; there have been statements here and there from Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, and their respective caucuses denouncing the administration and demanding to hear from the GSA about the delayed transition. But this historic and extraordinary effort to overturn the results of an American presidential election probably should have been met with a historic and extraordinary response from the party that won it—Democrats, as a unit, going to the press and the public every day demanding Trump’s concession and waxing lyrical about American democracy. Instead, Democratic leaders spent much of the last few weeks training their fire on progressives and policing activists.

Last week, CNN’s Manu Raju reported that Democratic reticence has been intentional. “Democrats are trying to avoid turning Trump’s refusal to accept the election results into a partisan fight, believing Trump will be in an untenable position if more Republicans join their calls to let the transition officially begin as the President’s legal case continues to collapse and states begin certifying the election results,” he wrote. “Moreover, seeking to enforce subpoenas to administration officials who play a key role in the transition process could take weeks to play out if the White House fights them, potentially going beyond January 20, when Biden will be sworn into office, Democrats say.”

None of this should come as any surprise. Democrats also intentionally dragged their heels on Trump’s impeachment for as long as they could, even after the long-awaited and vaunted Mueller investigation produced evidence of obstruction of justice, on precisely the same grounds: Wait for Republicans to jump in, and the party will come off looking better for its patience, for avoiding legal messiness, and for establishing a bipartisan front. “Impeachment is so divisive to the country,” Pelosi told The Washington Post in March 2019, “that unless there’s something so compelling and overwhelming and bipartisan, I don’t think we should go down that path because it divides the country.” Months later, her hand was forced by the revelation Trump had tried to coerce Ukraine into investigating Hunter Biden.

There’s nothing Democrats can do—or avoid doing—to bridge the partisan divide. Our very situation now is proof of this. Nothing about Biden’s pitch for unity and bipartisanship has discouraged the right from believing or pretending to believe that he, and maybe the Venezuelans, have perpetrated a massive fraud against the American people. But the dream of comity lives on: Polls have shown that the public and Democrats especially are still invested in bipartisanship as a political value, and revulsion for Trump hasn’t quite rubbed off on the Republican Party as a whole, particularly among the moderate suburbanites who swung so dramatically for Biden in the election. With Trump gone, these voters could swing back toward a more ordinary Republican just as dramatically—a possibility foreshadowed not only by Republicans’ surprisingly good performance down-ballot this year but in the sky-high popularity of blue-state Republican moderates like Massachusetts’s Charlie Baker and Maryland’s Larry Hogan. And the erosion in Democratic support among Hispanic and Black voters will obviously remain cause for concern. If notable shares of each were willing to back Trump despite his overt bigotry, how might more subdued conservatives perform in the years ahead?

The opposition party will end its term out of the White House without having done much to engender sustained opposition to the GOP. Now that task will fall to activists on the outside. One drama that’s played out in the background of the month’s events should be instructive for them. The legal profession has been roiled since the election by a movement against the firms Porter Wright and Jones Day, which have been representing the Trump campaign in its frivolous lawsuits. Lawyers were subjected to pressure campaigns, law students pledged not to work at either firm, and the specter was raised of a boycott against Jones Day’s other major clients, including General Motors. There were even pickets outside both firms’ offices. And all of this has seemingly yielded results. Earlier this month, Porter Wright abandoned one of Trump’s lawsuits, and Jones Day has reportedly decided not to take on any more election cases.

This was white-collar warfare, but there’s a broad lesson, too. Organizers who understood the Trump campaign as an institution dependent on other institutions and firms devised and carried out a strategy to undermine those relationships; their success has evidently had a concrete impact on Trump’s shenanigans. There’s no reason why the same kind of approach can’t be taken against the Republican Party as a whole. Its party organizations, the sponsors of its events, the firms that service it—the web of interdependencies in conservative politics is a web of potential pressure points. If Democrats can’t weaken the GOP through democratic reforms in Congress, and are unwilling to rally the public against it, activists should do what they can outside the halls of power with their own bullhorns and their own ingenuity.