A green young tailor’s assistant is summoned to see a high-flying prostitute. Their encounter lasts a few minutes, but his ensuing fixation on her is permanent. That’s a good investment on her part: He makes her exquisite dresses and is so devoted that he eventually stops charging for them. He even pays her rent after her fortunes decline, which they do in spectacular nineteenth-century fashion—her looks begin to slip, the fancier suitors drop away, degradation and penury follow, and she develops a mysterious illness we gather will be fatal.

This ought to be the plot of an operetta. In fact, it’s that of Wong Kar-wai’s The Hand, the only erotic section of Eros (2004), an otherwise unredeemed anthology film with contributions by Michelangelo Antonioni and Steven Soderbergh, now rereleased by itself in an extended cut as part of the Hong Kong auteur’s U.S. retrospective, The World of Wong Kar Wai. Though The Hand is by no means his best work, its qualities are instructive. Many of Wong’s feature films have been built from two or three shorter stories of this kind, in which the people and their relationships are immediately recognizable, you don’t need much fleshing out of their individual histories, and even the dialogue is barely required. The drama is all visual and emotional, as in a silent film: A scene where the tailor, alone, puts his hands inside a dress he’s altering for her conveys the whole arc of the affair.

Wong’s alienated romances travel easily across languages and cultures: While they’re concerned with existential questions of loss and freedom, their frenetic visual experimentalism and fragmentary structures give them a postmodern sensibility that puts melodrama, noir, Hitchcock, and the French New Wave through an MTV blender. The result, though full of startling and sensational pleasures, can have an eerie familiarity for urban viewers under late capitalism. This is a world we know, heightened and chaotic, sped up and slowed down, with the line between past and future, between what’s inside and outside us, blurred and fractured.

Yet Wong’s work is more locally specific than it may first appear—all his major films are in a sense about the emotional impasse represented by Hong Kong in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Though they play with different genres and imagery, all his films are love stories, and the most powerfully realized of them have an allegorical force and depth. They express a personal response to that anxious period, following the mid-1980s agreement to hand over control of Hong Kong from the British to the Chinese in 1997, with the promise that for the ensuing 50 years (until the end of 2046, a number thus freighted with meaning in Wong’s work) economic and social life there would continue unchanged, and the many signs to the contrary after Tiananmen Square.

That context saturates his films’ treatment of the more universal problems of love—autonomy, control, betrayal, disconnection—and their consonant preoccupation with time, a lost past and a promised future, both equally inscrutable. It’s no coincidence that the films in which these struggles are conveyed with greatest intensity are those that strategically displace them in time. A recurring setting is the Shanghainese community of early 1960s Hong Kong, which Wong conjured for Days of Being Wild (1990); his masterpiece, In the Mood for Love (2000); and the loose sequel to those two films, 2046 (2004). It’s a doubly lost world, in that its inhabitants have left China but not yet blended their ways with those of the locals, and in that Wong spent his childhood there, separated from his siblings and slow to assimilate. It’s a place of nostalgia for him, a partially invented past in which clothes and food and telephones are laden with emotional significance, and can hold a long shot by themselves.

The current retrospective, which marks the twentieth anniversary of In the Mood for Love, offers restorations of several of his best films but includes nothing after 2000, save the director’s cut of The Hand. It’s a striking opportunity, in the wake of Hong Kong’s prolonged street protests and the imposition of the draconian national security law, to revisit Wong’s portrait of a place that no longer exists, even in fantasy—particularly because his version of Hong Kong always exuded a sense of its own existence as conditional. The threat of loss is what gives any love story its power, but Wong’s career has been an experiment in deconstruction: His films disperse their painful endings throughout the action to be encountered over and over, and evoke a place you can’t belong in or hold on to, even though you are inventing it moment by moment.

Wong Kar-Wai emerged as a director in the late 1980s, amid the wave of Hong Kong crime action capers exemplified by John Woo. His early movies worked within popular genres, but his auteurist ambitions were immediately obvious. His debut, As Tears Go By (1988), yanked the structure of a conventional gangster movie to indulge touches of the operatic interiority that would increasingly characterize his work; 1994’s Ashes of Time was a lackadaisical take on the martial-arts epic that pointedly denied audiences its usual satisfactions.

In the 1990s, he focused on ever-intensifying mood pieces, often switching in and out of black and white, or isolating characters in slow motion while crowds speed and blur around them. Increasing international acclaim and support from admirers like Quentin Tarantino allowed him to keep funding personal, improvisatory projects despite several commercial flops. Days of Being Wild follows the meandering loves of a playboy whose adoptive mother won’t tell him who his biological parents are. The colors are muted, and there’s a pervasive sense of rootless fragility, as characters drift between cramped indoor spaces and rainy nightscapes. The protagonist claims he won’t know which woman he loved till the end of his life, so that meaning, and plot, are always deferred. The film’s central metaphor is of a legless bird that can never land anywhere until it’s ready to die—freedom figured as its own kind of trap.

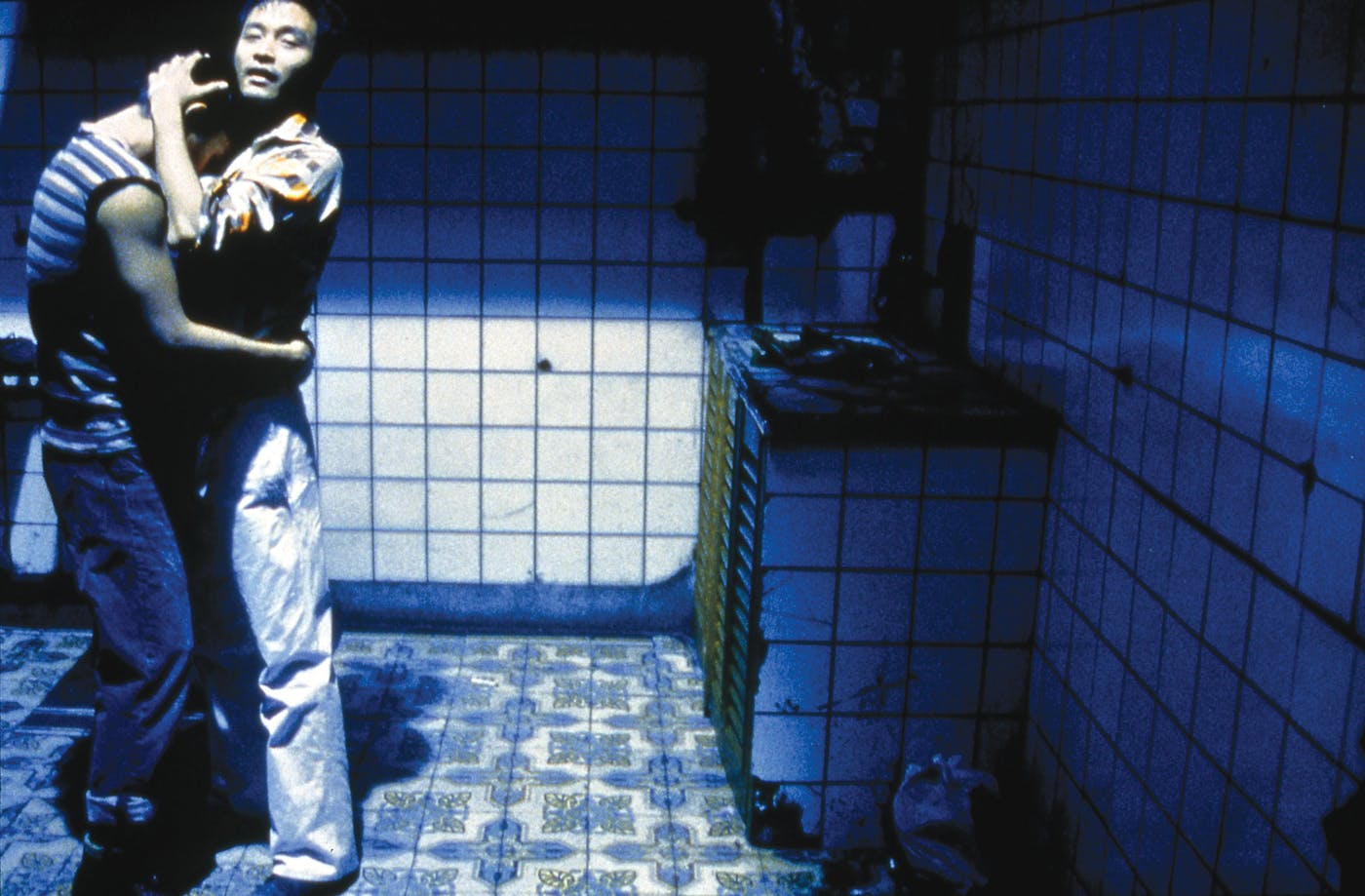

That blend of claustrophobia and precariousness is key to Wong’s work: The historical uncertainties of late-twentieth-century Hong Kong, though often only obliquely hinted at within his films, shape the texture of all his characters’ private lives. His most upbeat, playful treatment of the theme is Chungking Express (1994), which gave him his international breakthrough. It still has an exuberance that feels more or less untethered from its actual content, as if the audience is being invited to join in the director’s enjoyment of his own freedom to experiment. The film consists of the separate romantic misadventures of two cops we know by their ID numbers. Their stories are not interwoven, but presented consecutively, linked only by the fact that they both frequent the same fast-food joint. Characters you attach to in the first half never reappear. The love affair in the second half is conducted in a glancing, indirect fashion—one lover secretly visits the other’s empty apartment, rearranging and replacing small items in it. That sense of whimsy, contingency, and fragile connection suffuses the film: One character collects tins of pineapple with a May 1 expiry date, and muses on how love or, by implication, any given way of living must have its expiration. Such adorably stoned voice-overs also double as sly references to the impending handover to China.

Meanwhile, the texture of everyday life in Hong Kong is lovingly conveyed: You know far more about the detail of the diner staff’s work routines than you do about their personalities or histories, and you understand their inner lives mainly because these seep so extravagantly into the physical environment (and vice versa). The policemen themselves are exceptions: You never see them work, and they are not, in any case, presented as the kind of people you can imagine arresting anyone; they operate more like flaneurs frolicking through the city. That above all marks the movie’s setting as a kind of dreamscape, a Hong Kong of the mind, one that’s jarring to revisit in 2020, when fears about the future have left the realm of abstraction, and no one could pull off casting a cop as his everyman.

Wong’s tone darkened in Happy Together (1997), which is set just before the handover but sends its male lovers to Argentina. The question of belonging is vexed throughout. The opening shots show the protagonists’ passports, which designate them “British National (Overseas),” and then one suggests to the other, “Let’s start over”; later we’ll see the narrator try to cling on to the doomed affair by confiscating his lover’s passport. As well as focusing on a love feared to be more under threat post-1997, the film was released with the subtitle “A Story About Reunion,” giving its exploration of a long uneasy partnership a more openly political valence. Yet Wong remained constitutionally anti-polemical—his interest is not in political realities but in the pressures they subtly exert on the inner life. Even at his most maximalist, Wong has a fondness for the unsaid—a phone rings in an empty booth, an important letter goes unopened, a secret is whispered into a hole or recorded on a tape and later found to be unintelligible.

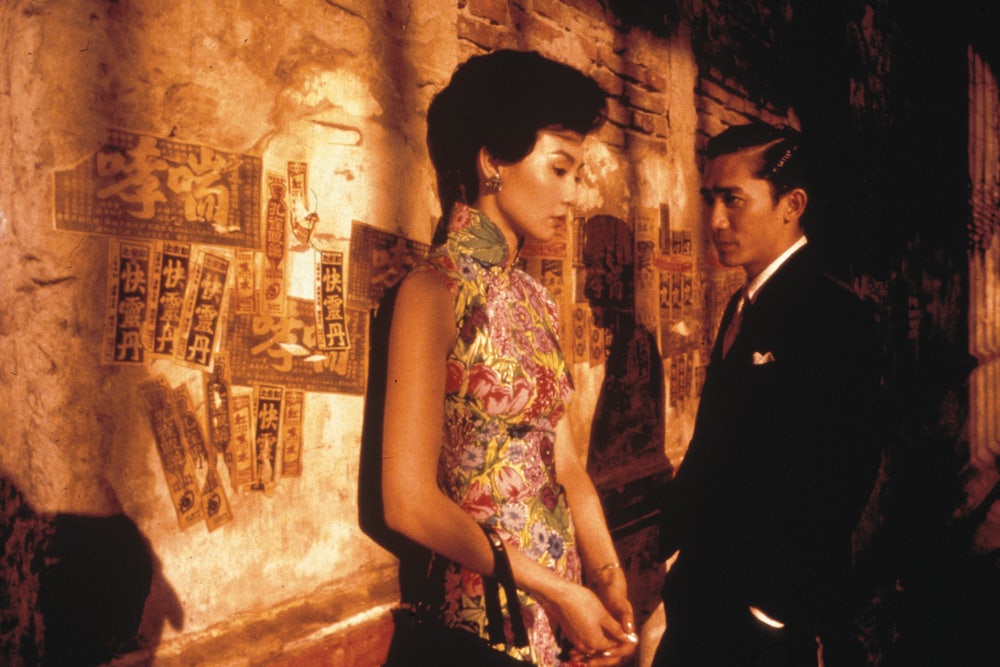

In the Mood for love marked a shift. Whereas Wong’s earlier films were freewheeling, the theme of this movie is restraint. Two strangers, Mrs. Chan (Maggie Cheung) and Mr. Chow (Tony Leung), rent rooms in adjacent apartments with their spouses, who are often absent. After working out that the spouses are having an affair, they begin spending more time together, trying to understand what has happened and keeping each other company. They grow closer, attracting gossipy disapproval from their landladies, and even meet in a hotel room (numbered “2046”) to work on writing a story together. Nothing is consummated and little is said. Yet much is expressed in the film’s saturated colors, the score’s Latin American love songs and signature waltz, and the corresponding quick-quick-slow choreography of camerawork and small gestures that repeat with variations as time passes. Characters are glimpsed in mirrors, behind curtains and doors or down hallways, passing each other in stairwells. A hand tenses against a table during a phone call. The back of Mrs. Chan’s head obscures the face of the landlady warning that she’s going out too often for a married woman, so that the viewer is left to focus on Mrs. Chan’s nervous hand picking at her bracelet. There’s the sense of a social world that’s all precise ritual and no privacy, with unexpressed emotion coursing underneath.

The restraint between the lovers is accentuated by an accompanying theatricality. One night, stuck sheltering from the rain together, they agree to rehearse a parting scene. The camera follows her hand, first clasped in his, then letting go and moving to clutch her other arm, so that we sweep upward with it to a close-up of her face turning to the wall, with his figure retreating down the street behind her. The screen is briefly black as we hear her sobbing, and he reminds her, “It isn’t real,” though it soon will be.

A couple of scenes in In the Mood for Love unexpectedly remind the viewer of a larger, airier world outside the one that’s been so exquisitely evoked. At one point, Mr. Chow talks to a friend in a café about how to cope with secrets. “I’d just go to get laid,” the man tells him, casually dismissing the film’s whole ruling concept of a life defined by concealed passions and disappointments. “I’m just an average guy. I don’t have secrets like you.” It’s a characteristic trick, one that’s pulled several times near the end of the film: The camera returns to the landlady’s apartment after she has left an increasingly unstable Hong Kong; it spends several minutes sweeping along Cambodian ruins. Abruptly, the events we’ve been following in such aching proximity are confirmed as small and insignificant—which only makes them more painful.

2046 is in a sense a feature-length version of this effect, a spiraling blend of period piece and futuristic science fiction, in which a more debauched version of Leung’s Chow character tries to move into apartment 2046 (where a woman he knows has just been stabbed) and writes a novel about time-traveling to a place called 2046 in the year 2046. His often frustrated and circuitous affairs with several women overlap with the android love story he’s devising. The characters speak to one another in different dialects, and the same questions—“Why can’t it be like it was before?”; “Will you leave with me?”—are asked but go unanswered. Several scenes take place on Christmas Eve, in an apparent reference to the date of Hong Kong’s surrender to Japan during World War II.

Here the fraught and hyper-subjective relationship with past and future is cranked up to 11. The protagonist speaks of having had a happy ending in his grasp and having let it slip away; one of his paramours sends a message asking him to change the ending of the story he’s written, as it’s too sad. “Love is all a matter of timing,” he says, “it’s no good meeting the right person too soon or too late. If I’d lived in another time or place, my story might have had a very different ending.” This is the film in which the existentialist romance is most explicitly linked to the historical moment. People go to “2046,” Leung’s character muses, to regain their lost memories: “In 2046, nothing ever changes. But no one really knows if that’s true or not. Because nobody has ever come back.”

Since so many of Wong Kar-wai’s films turn on romance, it’s striking that love tends to be portrayed less as a specific bond between unique individuals than as a matter of chance, of repetitions and fixed roles that could be filled by almost anyone who came along. People in his films meet again and fail to recognize each other, pick their partners at random, worry that the person they’re with now will soon forget them. The effect is enhanced by Wong’s casting of several of the same charismatic actors from film to film: Maggie Cheung, Leslie Cheung, Faye Wong, and above all Tony Leung, who frequently serves as a kind of alter ego, appear and reappear in different combinations across his works.

That doesn’t make their affairs any less wrenching. Wong has a melodramatist’s respect for emotional cliché: The sense that expressions and feelings have been reiterated in so many times and places and ads and music videos doesn’t make the experience of them less devastating or euphoric—if anything, more so. Mr. Chow tells Mrs. Chan that he had thought the two of them would be able to practice impersonating their faithless spouses to understand how the betrayal happened without actually falling in love themselves, but he finds that it’s impossible—if you take the same steps with someone, the same feelings will naturally follow. That’s what gives melodrama, like myth, its recursive power: The individual is ground in the gears of something that feels like fate, the more painful because those gears operate most powerfully inside her own psyche. You helplessly repeat patterns you absorbed too early to understand them—familial patterns, but also larger societal ones.

If there’s to be another major phase of Wong Kar-wai’s work in a similarly rich vein, it has yet to emerge. In the last 15 years, he has made only My Blueberry Nights (2007), a limp English-language road-trip film set in the United States, in which his style and sensibility lacked what had anchored them in the previous work; The Grandmaster (2013), a biopic of Ip Man, who trained Bruce Lee; and a forthcoming project set in booming 1990s Shanghai. In an apt form of emotional time travel, at this moment it’s the work he made in the first 15 years of his career that feels most alive. At their best, those films have the eerie vividness of a lost place, one whose every detail has had to be reconstructed from memory.