Chicago, in 1871, was alive to the giddy possibilities of modernity. The city had shot up from a flat expanse of grasses and wild garlic plants nearly overnight. In 1830, it had possessed a population of less than 100. Four decades later, its 330,000 inhabitants thronged the crowded streets, filling the vast lumber piles, grain silos, and stockyards to the brim. This seemed, to many, less urban growth than a force of nature.

Yet nature is often unkind. On October 8, a fire that started in the city’s West Division tore through Chicago’s densely packed grid, feeding so hungrily that balls of flame shot into the sky. It seemed that the “dogs of hell were upon the housetops,” the Chicago Tribune’s editor remembered, “bounding from one to another.” The conflagration destroyed a third of the city’s buildings.

Fires were distressingly common. One reason the Great Fire of October 8 spread so far is that Chicago’s firemen were exhausted from having fought another serious blaze the night before, one that did a million dollars in damage. The October 7 fire hit an area known to insurance men as the “Red Flash,” because of its propensity to ignite. Even the big fire, the October 8 one, wasn’t all that unusual: The same day, a fire in Peshtigo, Wisconsin, killed six times as many people as the Chicago fire did. Peshtigo (actual town motto: “Home of the Great Peshtigo Fire”) was a lumber town, and nearly the whole place went up. The day after, October 9, the core of Urbana burned down.

The next year, 1872, Boston had its Great Fire. The year after, Portland did—Portland, Oregon, that is, though Portland, Maine, had suffered a major conflagration a few years before that left 10,000 people homeless. In 1874, it was Chicago’s turn again. A large fire torched its downtown, converting another 47 acres to ash.

This was more than bad luck or bad zoning. It was the predictable consequence of a major fact about the United States. Its cities were made, like nearly everything else in the country, from wood.

It is strange, when you think about it, that the leading metropolises in one of the world’s most technologically advanced countries should have been fashioned out of humanity’s oldest building material. But we rarely think about it. Wood has a way of slipping from view. We characterize historical epochs by their most advanced materials and energy sources: the Stone, Copper, Bronze, and Iron Ages of prehistory and the recent fossil-fuel–powered Anthropocene. Yet, as the biologist Roland Ennos argues, if you looked at people’s actual lives, you’d conclude that nearly the whole of human history deserves a different title: the Age of Wood.

“Who can tell of every use that wood has?” the theologian Martin Luther once asked. To chronicle them all, as Ennos aims to do, is to write a history of the world, because once you look for wood, you see it everywhere. It has been not only a ubiquitous presence but also a driving force, helping to explain the European colonization of the Americas or the rapid expansion of the United States. More to the point, in emphasizing how resolutely wooden the past has been, Ennos shows the deep continuities that connected Luther’s day to prehistoric times—and just how abrupt our recent ejection from the wooden age has been.

Ennos specializes in biomechanics and writes with an appreciative eye for wood’s physical qualities. Two stand out in his view, and both appear to be evolutionary accidents, in that they confer no obvious advantage on trees. First, when you break wood off a living tree and let it dry, it stiffens without losing strength or toughness. Very few materials share this property—bone, horn, and fingernail all weaken as they desiccate. The second “fortuitous” property of dead wood is that it’s flammable. These twin serendipities account for wood’s two great uses: You can build with it, and you can burn it.

A sense of just how useful wood is can be gleaned from the human form. We are, in profound ways, shaped by wood. Binocular vision, hands rather than paws, and differentiated front and hind limbs, Ennos notes, are not human features so much as they are animals-living-in-trees features. We share them with our primate cousins; they allowed our ancestors to navigate arboreal canopies. It may also be that great apes’ large and energy-intensive brains evolved by favoring individuals who could make complex calculations about the mechanics of branches—crucial for heavy tree-dwellers. Certainly, great apes have a feel for wood. All of them can build sophisticated nests in trees, and all can craft wooden tools. The savanna chimpanzees of Senegal strip branches and sharpen them with their teeth to fashion spears and hunt other primates.

All great apes use wood as a material; humans specifically use it for fuel. Again, our bodies tell the tale. Human mouths and digestive tracts are fitted for soft, flame-cooked foods. Our atypically large brains, in fact, depend on the energy subsidy that comes from cooking. Ennos notes that we possess another “extremely unusual trait for terrestrial mammals”: hairlessness. Not having a pelt helps you avoid disease-bearing bedbugs, lice, and fleas, but it makes you cold. This evolutionary trade-off was presumably worthwhile for early humans only because they could build wooden shelters and fires.

And they did, all the time, even if wood doesn’t feature heavily in our stereotypes of the Paleolithic. What do you call an era when people hunted with wooden spears, dug up roots and bulbs with sticks, cooked their food on wooden poles, fed their fires with logs and branches, lived in wooden huts, and used rocks to scrape animal hides? The Stone Age, apparently. Ennos rolls his eyes at this fixation with minerals. It seems especially wrongheaded to focus on early humans’ stone scrapers because much of what they did with those crude implements was craft wood. In fact, he continues, most early technological advances didn’t replace wood so much as allow new uses of it. Copper and bronze permitted the manufacture of plank ships and wooden wheels. Iron gave rise to barrels, longships, and large wooden buildings.

One of the most famous vestiges of prehistoric times is Stonehenge, a circular grouping of hefty megaliths. But what, Ennos asks, about Woodhenge, a similarly arranged monument two miles away? Archaeological evidence suggests it must have been an “impressive structure,” too—slightly larger in diameter than Stonehenge. Yet all of that wood has rotted away in the intervening four millennia, leaving only post holes, which are today marked with uninspiring concrete stumps.

It’s a fitting metaphor. Up until a century or two ago, the human environment was nearly all wood. It’s just that the wood has decomposed, leaving only the stones and metals that now dominate our sense of the past. This mineral-centered scheme of history divides neatly into epochs, emphasizing the stepwise progression from one to the next. But it overlooks the deep continuities that until quite recently have tied us to prehistoric times, making it in turn hard to see how unprecedented the modern age has been.

Nearly everywhere humans have gone, they have found trees. The United Nations contains 193 states, from the desert nation of Oman to mountainous Bhutan. Not one is treeless. All have native tree species, often in great abundance.

Few countries have enjoyed quite so much of that abundance, however, as the United States. It is where you can find the world’s biggest, tallest, and oldest trees. They have been a source of wealth and strength for the country. And a reminder of how much the fates of even modern countries have been tied to their woodlands.

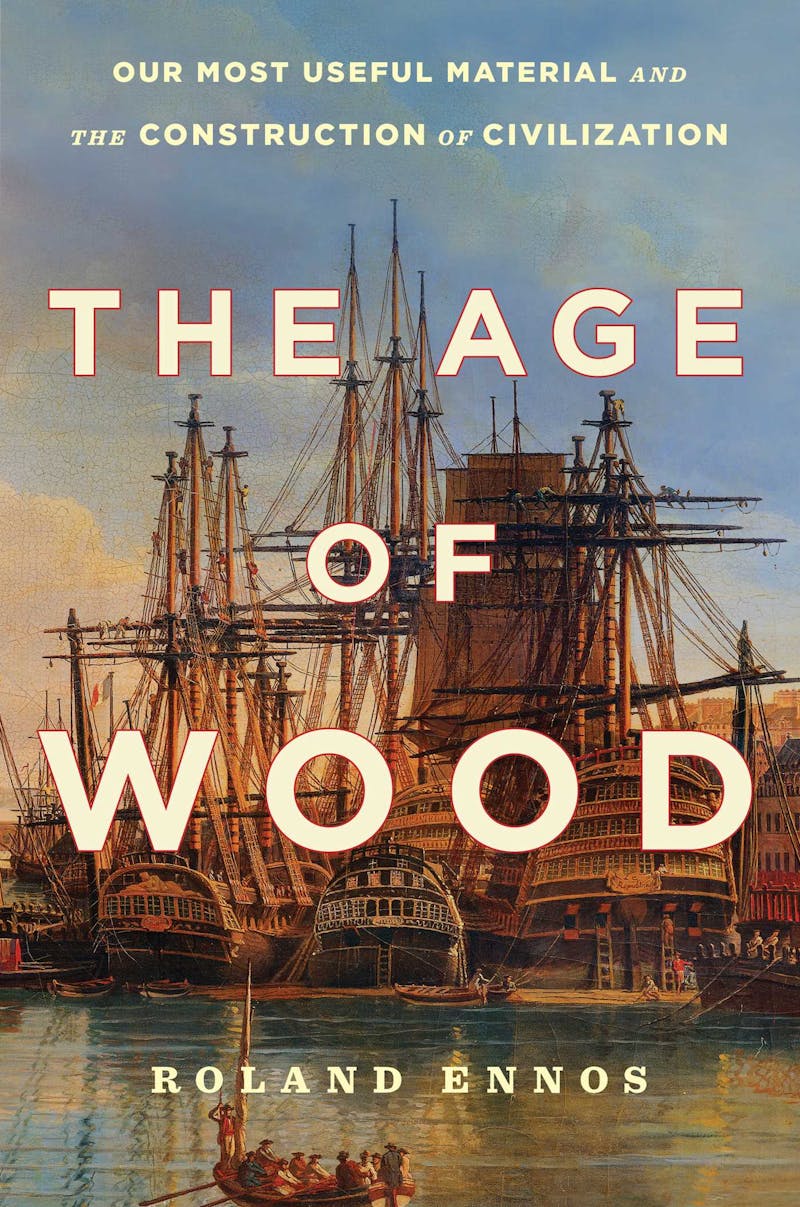

The British first set their sights on North America at a time when Western Europe was suffering a painful timber crisis. Iron smelting, naval construction, and the need for heating in an unusually cold era had all led to a “general destruction and waste of the woods,” one British observer noted in 1611. By this point, the government was already passing conservation laws to stop the wood hemorrhage. And the shivering masses were crowding into London, threatening unrest.

North America was different. It was, as its first European chronicler accurately put it, “full of very dense forests.” The desire to seize this timber, especially tall trees for ships’ masts, was an early motive for North American colonization. Early British ships carried settlers west and wood products east. Europeans, used to scrimping on wood, watched with astonishment as North American settlers spent it extravagantly. The choicest tree cuts, which would be reserved for the rich in England, were used by colonists for shingles. A British traveler was unnerved when she entered a rural woman’s home to find “such a log was blazing under her boilers as no fire-place in England would hold.” It looked “like the entire trunk of a pine, somewhat shortened,” yet the woman was using it as firewood.

The rapid nineteenth-century expansion of white settlement across North America was a wood-based undertaking. Ennos notes the balloon-frame architectural pattern that allowed people to convert planks into homes with just a saw, a hammer, and nails. Whereas mixed-material European construction relied on joiners, stone carvers, and masons, the all-wood balloon frame was a simple cage requiring little skill to erect. In the early days of Chicago, the likely birthplace of the balloon frame, one could commission a house at the start of the week and move in at the end.

The railroads, too, were wooden affairs. Though in Britain they were known as “iron roads,” in the United States they depended “to an almost unbelievable degree” on timber, the historian Brooke Hindle has written. The engines were iron, but the ties, cars, stations, brake shoes, bridges, and even sometimes the rails themselves were wood. So was the fuel: logs shoved into locomotive engines, each sending forth a shower of sparks—what Charles Dickens described as a “storm of fiery snow.”

As this “cyclone of civilization” rolled west “from the Atlantic toward the setting sun,” the “forests of untold centuries were swept away.” The Potawatomi author Simon Pokagon published those words in 1893 in a book written not on paper but on the bark of the white birch. It was a reminder, he said, of the world that was lost as the trees came down and the wooden cities arose.

And they were wooden. When Chicago burned in 1871, it wasn’t just the wooden buildings that caught flame, but the wood-paved streets and sidewalks, too, a burning gridiron that carried the conflagration from one block to the next.

Wood, as Chicagoans learned, is both a building material and a fuel. The Industrial Revolution emanating from Britain would eventually end the reign of wood, and it would do so by putting forth replacements in both realms. The wood-starved British fed their steam engines with coal, inaugurating the age of fossil fuels. Those fossil fuels then allowed engineers to fabricate a world of iron, steel, concrete, and ultimately plastic.

Coal contains around five times as much energy as wood by volume, and it is much easier to handle and store. The problem was that much of it, in Britain, lay underground and underwater—one early English mine owner needed 500 horses yoked to a bucket chain to keep his mineshaft drained. The breakthrough was the improved steam engine of 1776, which could use coal to pump out the flooded mines, greatly extending the reach of British miners. Suddenly, the British had an enormous and easily accessible stock of free energy beneath their feet.

Transcending wood meant escaping its physical limits. Wood-fueled fires can only burn so hot, wood-built edifices can only rise so high. Ennos points out that the largest ship in the world in 1514, the Henry Grace à Dieu in the English king’s fleet, was no larger than the great ships of antiquity. The age of wood had been an age of relative stasis, with limited outlooks and constrained possibilities. Wood, for all its wonders, is a stubborn material, better suited to time-consuming artisanal work than mass production. By replacing it, first as a fuel and then as a material, the British exited a long era of placid economic growth and entered a dizzying time of unbounded possibility.

Able to more readily create high heats and run powerful machines, British industrialists produced a flood of new goods to substitute for the old wooden ones they’d used for ages. “Cheap pottery replaced wooden bowls and plates,” Ennos writes. “Pewter and glass tankards replaced wooden goblets.” Iron was not new, but the idea that manufacturers could churn out cheap cast-iron pots, stoves, and cannon was. Bridges got longer, buildings higher, and navies stronger. By 1800, British coal had wiped out wood as a source of fuel, and it was generating 20 times the energy that wood had provided the country in 1650.

The heavily forested United States “remained firmly in the age of wood” during Britain’s coal transition, Ennos notes. U.S. ironworkers were using wood-derived charcoal more than coal until the latter half of the nineteenth century—some were still using charcoal until the end of the 1920s. Yet if the United States was slow to swap coal for wood, it was an early adopter of another fossil fuel: oil.

That the same country that had enjoyed an unspeakable abundance of timber should also possess great reservoirs of oil seems like a grand geopolitical injustice. Nevertheless, the enormous gusher of petroleum spurting up in Spindletop, Texas, in January 1901 made it clear that sometimes life just isn’t fair. The east Texas bounty inaugurated a century of oil, and a century of U.S. dominance. Wells operated in the British West Indies, Dutch East Indies, and Russian Empire, but nothing rivaled the mammoth oil corporations of the United States.

By the 1950s, the twice-blessed country had undergone a full oil revolution. As gasoline, petroleum fueled the automobiles that jammed its streets and the planes that filled its skies. Wood still had its uses, but more often as plywood, a composite product using petroleum-based resins. Meanwhile, another petroleum product, plastic, became the new basis of U.S. consumer culture in the form of Tupperware, Barbie dolls, credit cards, Styrofoam, Saran wrap, vinyl records, linoleum floors, nylon clothes, and Lycra bras.

“The whole world can be plasticized,” observed the philosopher Roland Barthes, rightly. He was born in 1915, meaning that while he could envision an all-plastic future, his lifespan overlapped with those of individuals who had known the all-wooden past. Two or three generations is about all it took to unmoor humanity from the substance it had relied on since the birth of the species. In the space of a few decades, we left behind a world our bodies had evolved for and entered a synthetic one our minds could hardly comprehend.

The age of wood is over, yet Ennos hopes that aspects might return. Psychologists have suggested that being around wood is calming, and, compared to its fossil-fuel rivals, it’s easier on the environment. Happily, engineers can now join sawn planks together smoothly and durably into computer-designed shapes, making wood newly useful in construction. “Architects are no longer constrained by the size of trees,” Ennos writes. Last year, the Norwegian firm Voll Arkitekter built an 18-story timber skyscraper, and the University of British Columbia boasts a dormitory, Tallwood House, of a similar size. We’re learning, too, to make transparent wood to replace glass and “liquid wood” that can be molded like plastic. “The way seems to be open,” Ennos believes, “to a whole new low-carbon economy.”

Perhaps. But if wood is having a comeback as a material, it’s not having one as a fuel. There, we remain wedded to coal, oil, and natural gas. We once thought that the danger of the oil economy came from the plastic clogging up the oceans, and indeed those oceans will probably contain more plastic than fish within 30 years, according to the World Economic Forum. Yet we now know that the far greater danger is what we are doing to the climate by powering our grids and vehicles with fossil fuels.

The United States is on fire again, not its wooden cities but its desiccated West, reaching new peaks of flammability as the planet warms. Each megafire is a reminder of how destabilizing our exit from the wooden age has been. Nearly the whole of humanity, from the arboreal hominins of two million years ago to the urbanites of the late nineteenth century, lived in the shadow of trees. We’ve barely had time to grasp the consequences of abandoning wood for fossil fuels and plastics, much less prepare for them. Now the forests are burning and we’re traversing a trackless plain, with little of the past to guide us.