The quest for authenticity is perhaps the central obsession of modern food culture. Food today is a vehicle not only for sustenance or pleasure, but for a certain type of truth—for tastes and sensations that are true to their place and the experience of their creators. It would be a mistake to regard this quest as novel. In 1654, Nicolas de Bonnefons, a valet at the court of Louis XIV, published The Delights of the Country, a work of gastronomic philosophy containing a simple but revolutionary principle. “A cabbage soup,” he wrote, “should smell of cabbage; if it is made of leeks or turnips, then it should smell of leeks or turnips, and so forth.” Until that point, cooks had masked the main ingredients of a dish under a cloak of powerful spices. De Bonnefons urged them to spurn homogeneity in favor of a radical distinctiveness, and make every dish taste like the ingredients themselves: “What I say of soups, I mean to be understood as applicable in every instance, and to serve as a general rule for everything that is eaten.”

The best food, in de Bonnefons’s view, was food that tasted like itself, and subsequent generations were careful to preserve and refine this commitment. Alexandre Balthazar Laurent Grimod de la Reynière, a French aristocrat commonly viewed as the first restaurant reviewer, published The Gourmands’ Almanac—essentially, a guide to how to eat well—in 1803. He included a long section on “the nutritional calendar,” spelling out for readers, month by month, that boar, wild duck, spinach, and cardoons were best eaten in January; spring was a time for lamb, mackerel, and peas; and that the conscientious eater should absolutely avoid oysters in September. Two of the holy commandments of what we now know as “New American” cuisine—that we should eat only what is in season, and let individual ingredients “speak for themselves” on the plate—are neither uniquely American nor new. It has been the struggle of successive generations of chefs, food writers, and culinarians in this country to find a place for them in American food culture.

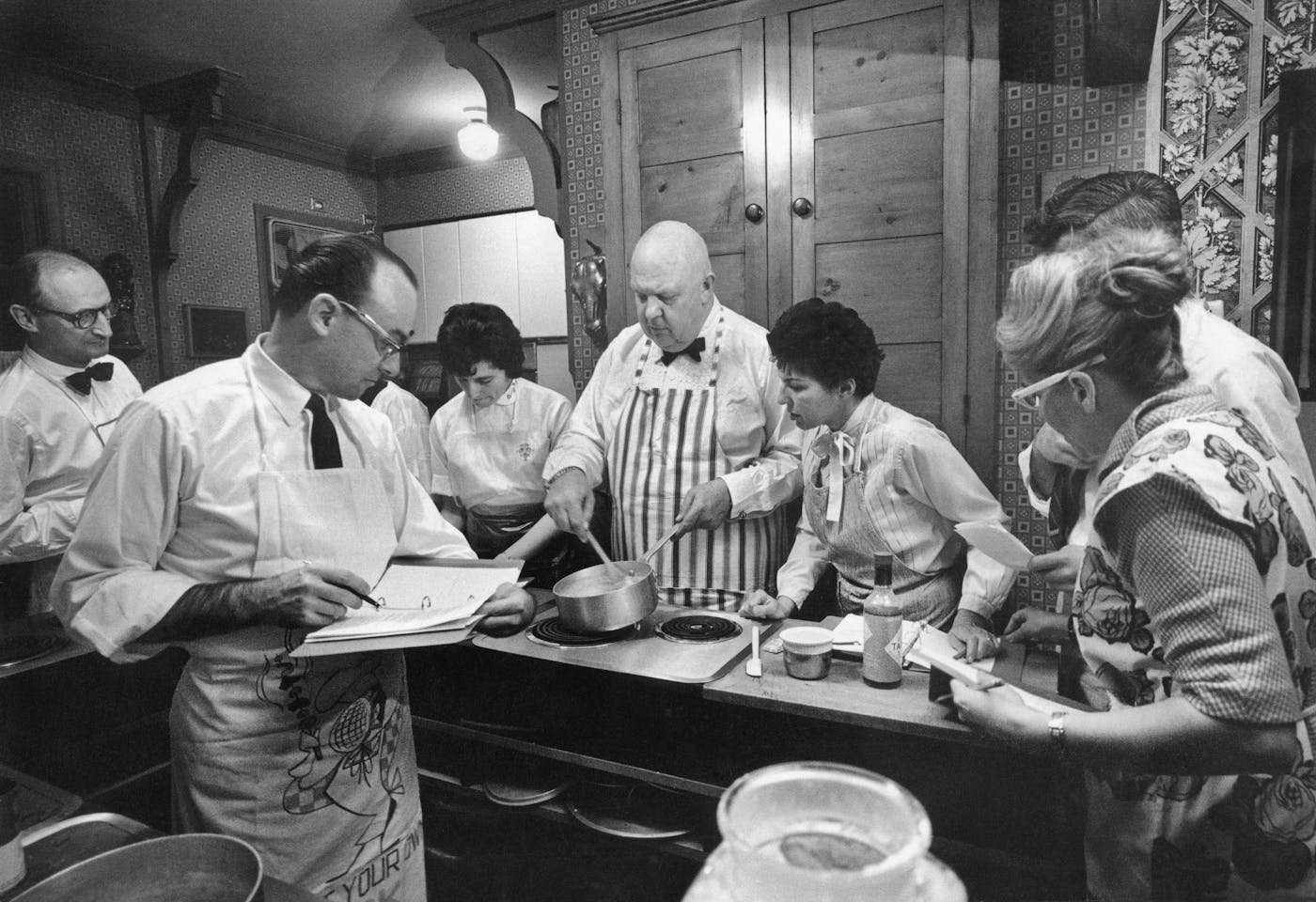

In the decades that followed World War II, no public figure prosecuted the cause of introducing America to seasonality, freshness, and culinary pleasure with greater vigor than James Beard. Gay, bow-tied, effusive, charismatic, and possessed of a lavish appetite, Beard had the misfortune to live in an era at once bigoted, repressed, paranoid, abstemious, and uninterestingly dressed. Today he is best known for the awards dispensed by his eponymous foundation, which remain, 35 years after his death at the age of 81, the most prestigious in the American restaurant industry. But of the man himself, contemporary memory is fairly shallow: He exists mostly in outline, as the bald, long-dead bon vivant beaming out at America’s eaters from illustrations, portraits, and the obverse of the culinary medals that bear his name. Unlike his contemporary Julia Child, Beard did not benefit from a longstanding presence on TV screens, and he has not been portrayed in a feature film. The Beard name is a seal of culinary quality, but the story of his life remains enigmatic and somehow remote.

As John Birdsall recounts in his new biography, The Man Who Ate Too Much: The Life of James Beard, Beard’s ascent to the summit of American cooking happened almost by accident, after a series of false starts and early meanderings. And it came, most importantly, at the cost of Beard’s own identity and voice as a gay man. In Birdsall’s painterly account, this initial sacrifice reverberated through Beard’s career, as he diminished his own collaborators’ contributions to his work, and peddled historical falsehoods in order to confer imagined glamour on the origins of a new American gourmet culture grasping for status and prestige. These aspects of Beard’s story—both his sins and his suffering—relate directly to many of the problems plaguing today’s food culture, in which debates over authority, identity, and appropriation had long been suppressed. American food’s divorce from politics was essential to its invention—an original sin that chefs and restaurant owners now have to reckon with as they attempt to right the inequities of the culinary house that Beard built.

Beard’s early life in Portland, Oregon, was a sketch in pleasure and compromise, the two forces he would eventually mobilize on his long journey to the center of American culinary life. From his energetic and demanding mother, a resourceful Englishwoman who fled the strictures of Victorian London in her late teens and established a solidly middle-class existence in the Pacific Northwest, he gained a love of food, high standards, and an enduring appreciation for the intimate connection between taste and place. From his mother’s marriage to his father, a distant and forlorn customs appraiser, Beard received an early education in the sacrifices needed to survive in a prejudiced world: His mother most likely was queer, but buried her sexuality beneath a straight union of convenience.

When Beard entered Reed College in 1920, his enormous frame—six-foot-three, 240 pounds—immediately made him a mark in the campus newspaper: One item had a history professor asking, “What made the tower of Pisa lean?” and Beard replying, “I don’t know—if I did I might try it.” For the 1920s, one imagines, this qualified as good-natured banter, but Beard soon became a target for institutional prejudice of a much darker variety. Reed College was in a parlous financial position, and public sentiment on homosexuality ran the gamut from intolerant to murderous. When Beard was discovered, midway through his freshman year, in an act of “indecency” with a young professor recently recruited to head up the new German department, Reed’s president, attempting to kill the scandal before it could become public and imperil the university’s standing among the local community, fired the professor and expelled Beard.

Everything about Beard’s career and the influence he wielded over American food culture—his obsessions as well as his elisions—needs to be understood within the context of this first encounter with institutional homophobia. “Years later,” Birdsall writes, “a friend remarked that James hated being gay. Maybe what James really hated was bearing the wounds of being gay in a world that never let them scar over.” The persona that Beard constructed for himself, and allowed others to construct for him, in the years that followed rested on the militant suppression of any hint of sexuality or sexual desire: Here was an authority on food and the good life so singular, so consumed by his mastery of the culinary canon, that he had time for nothing else. Politics, women, debates over social mores, collaborators worthy of public recognition—none could divert him from his obsessive course.

By the time Beard arrived in New York in the late 1930s, he’d endured a series of dead-end jobs, and his ambitions of becoming an opera singer had foundered on the obstacle of moderate talent. He found his calling when he discovered a gift for organizing the private cocktail parties and apartment gatherings that were the backbone of social life for New York’s gay men and women, still unable to express their authentic selves in public. (The State Liquor Authority deemed the mere presence of homosexuals in a bar sufficient grounds for a finding of “disorderly conduct,” which could lead to revocation of the establishment’s license.) The food Beard produced during the first moments of his gastronomic awakening was hardly revolutionary: tomatoes stuffed with chopped chicken, cornets of Genoa salami, calf’s tongues with Roquefort. There was much wrapping of ingredients around balls of cream. But a culinary education was quickly taking shape. From Bill Rhode, an aristocratic German immigrant with whom he formed the splendidly named catering company Hors d’Oeuvre Inc., Beard learned both the importance of shopping—the commitment to working with only the finest ingredients—and the skill of leavening his culinary creations with tales of fanciful origins. Rhode was a master bullshitter, regaling the fledgling company’s clientele with entirely invented anecdotes about the Duchess of Windsor’s corned beef balls or King Nikita of Montenegro’s preferences in stuffed eggplant; he claimed that Hors d’Oeuvre Inc.’s vichyssoise stretched all the way back to the court of Louis XIV, a figure so paranoid he sent the soup through so many tasters that it eventually arrived at his table ice cold.

Thanks to one of those serendipitous and vaguely literary society encounters that seemed to proliferate without effort in the years between the two world wars, Beard landed a deal to produce his first cookbook. When Hors d’Oeuvre and Canapés, With a Key to the Cocktail Party came out, Beard’s mastery of his new métier was on full display: not only in the cool confidence of the recipes, but also in Beard’s embroidery of his own expertise as a caterer and the casual, callous failure to give any kind of credit to Rhode or Rhode’s sister, whose creations appeared without attribution as Beard’s own. Beard presented Brioche en Surprise, a parsley-edged brioche sandwich filled with mayonnaise and onion that was the closest thing Hors d’Oeuvre Inc. had to a signature dish, as the specialty of an imaginary French salon, while a pineapple dessert was inspired by “a famous English hostess who entertained a great deal in the summer at her large country place.” The food was real, and the fiction was total.

Twenty further books followed, and though he went on to augment his success in other venues, such as the James Beard Cooking School, it was above all as a cookbook author that Beard cemented his reputation as the garrulous doyen of American cooking. It’s difficult to imagine a writer today being allowed the time to develop as Beard did: His “platform” as a virgin author was relatively slim, sales weren’t much better, and it wasn’t until The James Beard Cookbook came out in 1959 that Beard enjoyed his first genuine commercial and critical hit. The relative leniency of the postwar publishing environment gave him the space to perfect an identifiable philosophy of food, and New York granted him access to a network of patrons willing to fund the frequent European tours he took to nourish his culinary imagination. The tenets of that philosophy have become, in subsequent decades, relatively commonplace: freshness, seasonality, an emphasis on the use of local ingredients, and a preference wherever possible for drawing on the goods of the green market, the neighborhood providore, the artisan farmer, and the small-batch producer. But in the decades immediately following World War II, when Beard was at his most productive, advice such as this was genuinely radical.

America after the war, writes Birdsall, was “a nation more interested in the future than the past”—a bland and triumphal capitalist wasteland of fish sticks, frozen vegetables, bagels in a can, and TV dinners, in which homes sprouted with magical new cooking gadgets like the Cal Dek, the Smokadero stove, the Big Boy barbecue, and the Broil-Quik. Beard’s struggle was to convince Americans that there was another way, one that resurrected old cooking practices, paid homage to the bounty of each region’s produce, and did not recoil from the sight of whole animals or fresh vegetables, reveling instead in the possibilities of their unprocessed textures, flavors, and scents. At a time when the country was swooning over Adolph’s Meat Tenderizer and the Birds Eye frozen asparagus spear, Beard encouraged Americans to find glory in simplicity. “A much misunderstood word—gourmet,” he wrote in the introduction to the 1954 volume How to Eat Better for Less Money. “A boiled potato—a potato cooked to the point at which it bursts its tight skin and shows its snowy interior—can be gourmet food.”

To make his case, Beard adapted France’s cuisine bourgeoise for the American market, Anglicizing the names of certain dishes, turning down the volume on others considered too complicated or adventurous, and grafting American ingredients onto the rootstock of French recipes. Beard recast the omelette paysanne as his “Country Omelet,” with American smoky bacon subbing for the traditional salted pork belly, while daube emerged as “Braised Beef, Peasant Style,” a new type of American pot roast given a dash of flair via the addition of red wine, cognac, and thyme. In this way, Beard’s invention, “American food,” emerged as a concern cultishly devoted to the authenticity of taste even as it mined foreign culinary tradition. We were still, at this point, some way from Chez Panisse’s heirloom tomato salad, Gramercy Tavern’s coronation of the burger with a bonnet of Cabot clothbound cheddar, or squash blossoms at Spago. But the train was in motion.

The voice of Beard’s early cookbooks was chatty, unfiltered, and unapologetically camp. His recipes were larded with terms like “chichi” and “doodadery”; at one point, he floated the suggestion that a new book about grill and rotisserie cooking be given the endearingly arch title doing it outdoors (“in small letters as if it were by e.e. cummings”). As Beard’s stature grew and he began to attract the interest of more prestigious publishing houses, that voice was gradually silenced; by the time The James Beard Cookbook appeared in 1959, it was gone almost completely—the gossipy asides and waspish digressions of his earlier work excised in favor of a narrative style that presented Beard as a practical man of action. “James Beard, Dean of American Cookery,” was the creation of editors and publishing executives who worked hard to minimize, and eventually erase, all traces of gayness from Beard’s voice and public personality. Beard was deflavorized even as he emerged as America’s apostle of taste; many of his books credit him not as James but as a manly Jim. This was, of course, the simple and heartless reality for all non-heterosexuals of Beard’s generation: “The central rule of being queer in the brutal era after the war,” writes Birdsall, was that “you never, ever publicly acknowledged being queer, or even hinted at it.”

The more interesting question is to consider the impact this erasure had on America’s food culture more broadly. Beard was one of several queer pioneers present at the creation of New American cuisine, a circle that included the cookbook author Richard Olney and the New York Times food editor Craig Claiborne. This was not the generation of gay liberation, but a generation or two before: The Stonewall rioters filled Beard with terror, as he observed them in late middle age. (Birdsall explored American food’s queer roots in a 2014 essay he wrote for Lucky Peach, which provided the spark for this biography.) The minimization of these pioneers’ queerness went hand in hand with the insulation of American food culture from the political engagements that a more open reckoning with prejudice and sexuality might have occasioned. It established limits beyond which food could not travel: into people’s private lives, the regulation of sexual norms, and all discussion of the cruelties perpetuated by the homophobic state.

Food became a neutral zone, apolitical and sexless, of pure pleasure. Food was play, indulgence, refinement, elegance: anything but politics. It offered escape from reality rather than confrontation with it, into a realm as sanitized of debate as the flavors on its plates were seasonal and clean. “I’m hungry!” James used to roar at the start of classes at his cooking school. It’s hard not to think that, forced to suppress his authentic personality and don the costume of an asexual, avuncular epicurean, he was also profoundly unhappy.

Beard was not a good writer. He remained an inveterate plagiarist, of both his own work as well as others’, until the end of his publishing days. And he consistently downplayed the contributions of his collaborators, many of them women. His editor-ghostwriters Isabel Errington Callvert and Ruth Norman, in particular, put years into hammering Beard’s messy prose into shape while receiving little pay and scant credit in return. Beard was both a victim and a perpetrator of multiple erasures, which Birdsall records in meticulous detail. In one especially egregious example, from 1954, Beard lifted recipes from one of his own forthcoming titles—to be published by Doubleday and co-written with Helen Brown, a pioneer of California cuisine—and inserted them without attribution or amendment, along with another recipe taken from Brown’s renowned West Coast Cook Book, in Jim Beard’s Complete Cookbook for Entertaining. “He not only used innumerable of my best ideas without credit, he used some that I have NOT used anywhere because I wanted them fresh for the Doubleday book,” Brown complained in a letter to their agent. When she confronted Beard, he deflected with an obvious lie. “When the mss was typed,” he wrote, “there were other sheets that got mixed up and around that weren’t supposed to be in it.”

It’s impossible to read all this without hearing echoes of contemporary controversies. Have we really moved on from Beard’s era? On the plate, yes, but elsewhere things are not so clear. We can laugh at Beard’s invention of a prerevolutionary backstory for his commercial charcoal sauce, but today’s hospitality industry remains a bain-marie of bullshit: a home for instant, non-Chinese experts on the food of Sichuan, or bars in gentrifying neighborhoods selling expensive wine in paper bags. In the ongoing debates over the whitewashing of ethnic food or the etiquette of kitchen credit, Beard is very much still with us: Between his “Braised Beef, Peasant Style” and cookbook writer Alison Roman’s chana-derived “The Stew,” between his failure to acknowledge collaborators and the recent marginalization of nonwhite contributors at Bon Appétit or the kerfuffle over credit for recipes developed at Los Angeles restaurant Sqirl, the lineage is clear.

America’s food industry has not shed the baggage of its foundation, though there is at last a willingness to engage with its legacy of unfairness. In recent months, the James Beard Foundation has itself moved to the center of this reckoning, announcing in late August that it was canceling its fabled food awards for 2020 and 2021. The official reason was pandemic-induced sensitivity to the struggles of the restaurant industry, but the real story quickly emerged: This year’s winners’ list did not include a single Black chef. As in previous years, the finalists skewed white and male, a double-punch of biases both unreflective of back-of-house reality and hopelessly out of step with the times. In a world of Jameses, we’re still getting Jimmed.

If today’s restaurant industry struggles with questions of attribution, originality, exploitation, and representation—struggles, in other words, to develop a politics—it’s in part because so much energy was spent at the genesis of “American food” sweeping such issues under the carpet. Reckoning with the inequities of the industry is also about unlearning the habits of the past. The story of Beard’s life invites us to recognize the violence that was done in the name of American cooking, and expand our understanding of authenticity to include not only what’s on the plate but everything around it: the norms, prejudices, economic wounds, environmental traumas, and other social forces that go into the production of food and culinary authority. It’s a reminder that food is part of culture, and terroir not simply a matter of the soil.