Immediately after the conclusion of Tuesday’s Supreme Court arguments concerning the bid of 18 red-state attorneys general, backed by the Trump administration, to strike the Affordable Care Act down in its entirety, the media—with uniformity—pronounced the law “likely to survive.” With a laser focus, these after-action accounts focused on strong indications that a majority, of at least five justices, is poised to hold that even if the Affordable Care Act’s “individual mandate” to purchase insurance is deemed unconstitutional, only that provision should be stricken. If the court takes that tack, its remedy would “sever” the mandate provision and leave the rest of the statute intact.

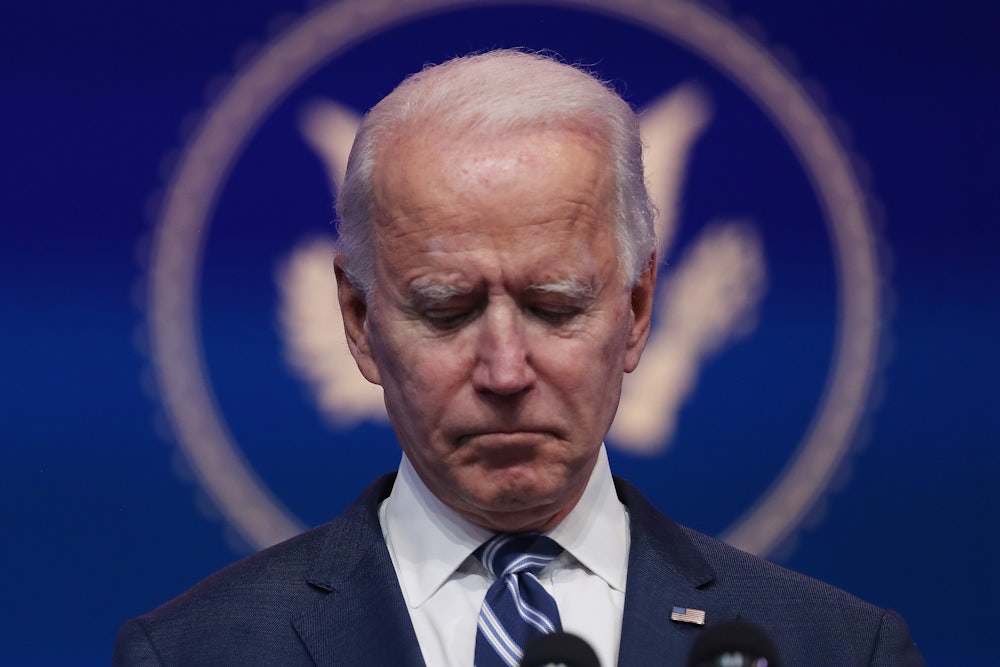

In effect, this would not damage the law at all. But that doesn’t mean the court’s conservative majority might not mete out some substantial harm. The manner in which it “saves” Obamacare, in fact, may imperil the rest of President-elect Joe Biden’s agenda.

Here, it helps to look back over some moments that went unremarked upon by the commentariat. During Tuesday’s oral argument, much of the justices’ questioning concerned another legal issue—“standing”—which is equally wonky but potentially far more consequential than “severability.” Standing is a fundamental separation of powers doctrine designed, in the words of Justice Byron White, to ensure that, “under our constitutional system,” unelected, life-tenured judges do not become “roving commissions assigned to pass judgment on the validity of the Nation’s laws” except when compelled to do so “out of the necessity of adjudicating rights in particular cases”: what the Constitution terms “cases” or “controversies.” In order to qualify a claim as such a matter—and indeed, get into court at all—would-be litigants must show that their grievance constitutes a “concrete injury.”

Any ordinary person would be baffled by the ACA’s opponents’ claim, in this case, that they were injured, concretely or otherwise, by Congress’s decision in 2017 to zero out the tax penalty prescribed by the original 2010 ACA to incentivize individuals to buy health insurance. With that revision, the law presents individuals with this choice: Buy insurance, or … nothing. There are no consequences, period. How can that constitute an injury? On this point, the Supreme Court’s answer has—most of the time—aligned with common sense: As an often-cited decision states, courts lack jurisdiction to “umpire debates concerning harmless empty shadows” and thus to give merely advisory opinions.

In his questioning on Tuesday, Chief Justice Roberts indicated that he may seek to use this case as a vehicle to reaffirm the Supreme Court’s strict standing precedents. By thus resting a slapdown of the ACA challenge on standing grounds, the court would signal sharp disapproval of the tendency of some lower court judges to brush standing rules aside in cases they consider top priorities—often, as in the current ACA challenge, political priorities. At one point, Roberts lauded standing as “an important doctrine—the only reason we have the authority to interpret the Constitution is because we have the responsibility of deciding actual cases, and that’s what standing filters out.”

On this issue, the chief justice’s was not the only voice. Justices Elena Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor, and Stephen Breyer, along with former Obama Solicitor General Don Verrilli, arguing for the House of Representatives to uphold the ACA, sought to reinforce this focus on standing. Echoing Roberts, Kagan admonished Trump’s Acting Solicitor General Jeffrey Wall: “The United States is usually pretty stingy about standing law, so it did surprise me, in much the way that it surprised the Chief Justice, that you’re coming in here with a theory which, to my mind, threatens to kind of explode standing doctrine.” Justices Clarence Thomas and Amy Coney Barrett also asked carefully prepared questions about standing, some of which appeared to suggest skepticism about ACA opponents’ work-around theory for evading Supreme Court standing doctrine.

Does it ultimately matter which hypertechnical jawbreaker the court invokes to save the ACA? Indeed, it could: If Roberts’s fellow conservatives accept his invitation to raise standing barriers, especially standing for state governments, that would signal that the newly right-shifted majority, going forward, is not comfortable serving as a transparently handy tool for its political allies on the right to advance their priorities. As you might imagine, those priorities will emphasize quashing high-profile Biden executive actions, on which the new administration will largely depend, unless Democrats next January win both Georgia Senate runoff elections and flip control of the Senate. If the other five conservative justices choose not to follow Roberts’s lead in this instance, however, it will signal an alliance with a larger universe of conservatives eager to stop, through litigation, the Biden administration’s governing agenda.

The pending challenge to the ACA is hardly the only example of how easy loose standing criteria can make it for political actors—state governors and attorneys general, in particular; especially the notoriously litigious Texas Office of the Attorney General—to forum-shop for partisan lower court judges, sometimes stalling administrative actions for months and years, or at least chilling or freezing in place threatened programs, and, ultimately, putting a steady diet of political hot potatoes on the Supreme Court’s calendar.

One of your authors rather painfully experienced this phenomenon a few years ago while defending one of President Barack Obama’s major immigration initiatives—Deferred Action on Parents of Americans—against just such a challenge organized by Greg Abbott, then Texas’s attorney general, now its governor. Abbott once described his typical workday: “I go into the office, I sue the federal government, and then I go home.” With the help of unabashedly anti-Obama and anti-immigrant Republican appointees to one of Texas’s federal district courts and to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, Abbott succeeded in shutting down DAPA, which would have deferred eligibility for deportation for four million undocumented immigrants, through the end of the Obama administration.

Eerily, on Thursday of this week, The Washington Post’s Greg Sargent gushed that President-elect Biden plans to move fast to implement a progressive immigration agenda, including to “fully restore the [Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals] program that protects hundreds of thousands of ‘Dreamers’ from deportation and provides them with work permits.” Texas’s Republican leaders have an off-the-shelf template for using the courts to shut down any such DACA restoration. But if the Supreme Court sternly rebuffs their current ACA challenge for lack of standing, they might feel obliged to leave that template on the shelf.

Historically, liberals have, no less than

conservatives, deployed Texas’s recipe for turning to the courts to check

hostile administrations and laws—often with good reason and sometimes with huge

impact. Perhaps the most dramatic

example is the court’s 2007 decision to grant the state of Massachusetts

standing to press its claim that the federal Environmental Protection Agency

possessed, and was obligated to exercise, authority to regulate greenhouse gas

emissions. The court went on to order the EPA to initiate a rulemaking proceeding, which yielded major motor vehicle

emissions controls that are still on the books despite Trump administration

cutbacks. Chief Justice Roberts

vehemently dissented from the court’s 5–4 grant of standing to Massachusetts,

and in particular to Justice John Stevens’s assertion, in his majority opinion,

that state governments’ “quasi-sovereign interests … entitle [them] to

special solicitude in our standing analysis.”

As a result of successes like Massachusetts v. EPA, environmental and other liberal interest groups reliant on litigation have reflexively, if understandably, favored loose standing barriers to challenging laws and executive policies they oppose.

But now, with a 6–3 Supreme Court conservative majority and over 200 Trump lower court appointees gleaned from what University of Pennsylvania law professor Stephen Burbank characterized as a Federalist Society–enabled “search for hard-wired ideologues [and] reliable policy agents,” liberal groups would be well advised to reconsider their approach to standing. They should recognize, as liberal Justices Kagan, Sotomayor, and Breyer indicated in this week’s oral argument, their stake in Chief Justice Roberts’s apparent yen to set a high bar to the sort of shenanigans that led to Texas putting the ACA in play in the courts this third time. In other words, now that liberals are playing defense—trying to preserve laws and executive actions in the face of a coming conservative onslaught—they need to adapt, much as any good sports team would when playing different teams with different strengths.

How this case comes out will also test the bona fides of Roberts’s frequent ostentatious assertions of commitment to keep the court above politics. To date, he has a mixed record on this score. More broadly, this will gauge how much sway he has with the other five conservative justices, to defuse perceptions that the court is as politically reliable as Donald Trump, Mitch McConnell, and Leonard Leo hope and trust it will be. These men may very well suffer the Affordable Care Act to live another day, if it means that Biden’s presidency can be more easily—and more mortally—wounded.