“I get it,” Mondaire Jones says into the camera, shaking his head. He is speaking on a Thursday night four weeks out from the election, to the virtual audience of a virtual rally hosted by Our Revolution, the PAC created by Bernie Sanders after his first presidential run in 2016; someone has just asked him about Joe Biden. Fresh off a primary victory in the wealthy, largely white suburbs of New York, Jones, who grew up in Section 8 housing in his district, is poised to become the first openly gay Black member of Congress. He got there on a platform of policies that Sanders championed and that Biden has largely rejected—measures like a Green New Deal and Medicare for All. So he opens with a proviso: “None of us … had Joe Biden as our first choice.” Still, he goes on, “I can’t do any of the things that I ran on without electing him president.”

In a post–Bernie Sanders electoral field, candidates like Jones and groups like Our Revolution face the awkward double-step of having to throw their support and organizational capacity behind a presidential candidate who has repudiated many of the broad social-democratic programs and working-class politics that they stand for. They are under no illusions about the odds of a Biden presidency suddenly pivoting to enact a bold progressive agenda. Instead, grassroots organizers on the left who found an ideological home in the Sanders campaign, as well as a sizable number of former Sanders operatives themselves, are all now in the position of fighting like hell to elect their own opponent.

The move may feel emotionally fraught, but the path is straightforward from a strategic perspective. “Voting is a tactic, period,” said Winnie Wong, a veteran of the Occupy movement and a former political adviser to Sanders. Wong is now a part of Vote Trump Out, one of a handful of campaigns devised by yet more Sanders staffers in the wake of his primary defeat. For those behind Vote Trump Out and its sister project, Not Him, Us (a play on Sanders’s own slogan, “Not Me, Us”), there is no question that defeating Donald Trump is necessary to realize any one of the majoritarian policies that Sanders ran on. As Jonathan Smucker, an organizer with Not Him, Us, put it, “For us to get anywhere, to put demands on the system, we need to have someone who is at the very least vulnerable to our pressure. Donald Trump is not vulnerable to our pressure.”

On November 4, organizers will wake up and see whether their ground game paid off; whether, in the days or weeks that may be required to count every vote, they won or lost. But the campaign is also bigger than one election: No matter what, the outreach, deep organizing, and local conversations about stakes and power they will have engaged in are precisely the kind of turnout strategy that Sanders tried to build but that organizers rightly observed will take longer than the course of one campaign cycle. That work has to penetrate deeper, pull more people in, and construct a coalition that strategizes and fights in all the battles to come. In the end, for many on the left, this moment, which has been billed as a once-in-a-lifetime event and a singular showdown between good and evil, is really about the essentially timeless work of building power.

Even if the electoral strategy is clear, the marketing campaign is more subtle. Many of those on the left who are waging collective struggles suddenly find that their short-term goal—evicting a fascist from the White House—aligns with the goals of the Democratic establishment. This presents something of a rhetorical challenge as they try to mobilize voters who see the party as lacking credibility and who were attracted to the Sanders campaign for this very reason. The crucial difference, these organizers insist, is that while party elites would have us vote Biden into office and then spend four years placidly receiving whatever milquetoast program he sees fit to roll out—you’ll see this articulated most explicitly by pundits fantasizing about a post-Biden return to a previous state of passive bliss—those agitating for climate justice or student debt cancellation see Biden as a brief detour on the long path to transformative politics, not an end unto himself. “This is necessarily a two-step campaign,” Dan Sherrell of Vote Trump Out told me. As the name of his organization would suggest, ending the current regime is the first step. The second step is to take position so that the moment Joe Biden steps into office, he finds a well-organized coalition breathing down his neck.

That’s a difficult strategy to realize, which is why the movement has to grow—so the demands can carry the weight necessary to win real concessions. Organizers today are wary of repeating the mistakes of the Obama campaign in 2008, when voters motivated by transformational politics helped push the candidate over the finish line and then took a step back, putting their trust in an administration that ultimately failed to deliver on many of their priorities. Still, “Blue No Matter Who” is much catchier than Vote for Joe Biden in order to avoid four more years of a proto-fascist and then immediately pressure him to enact a working-class agenda through sustained grassroots movements. These groups have had to be thoughtful about their messaging.

The first move is to be clear-eyed with voters about the limits of a Biden administration. “We’re not trying to sell Biden to the left,” Wong explained. Casting Biden as a kind of covert progressive is not just in bad faith, it’s bad strategy. It will ring hollow to the people Wong and her colleagues are trying to reach. Instead, the idea is to meet people where they’re at, including and especially if that means feeling disaffected about the state of electoral politics. There is no need to pretend that Biden and the Democratic Party will hand over anything willingly—they will need to be beaten. The approach, as Sherrell puts it, goes something like: “We don’t like this guy either, but he’s the target we’d far rather have in the White House.”

Then there is the issue of what Sherrell calls the “theater of individual actors” or what Jesse Myerson identified last month as the “voter-consumer” problem—the idea that voting in the presidential election is the stuff of our political identities, an act of self-expression that we exercise once every few years before leaving the rest of the work to the adults in elected office. As Vote Trump Out sees it, this tendency to reduce politics to a few national races only serves the interests of a liberal establishment that would no doubt prefer that working-class people grit their teeth, vote for the Democrat, and then stay out of the streets of cities run by Democrats, refrain from challenging incumbents in primary races, and rely on the necrotic incrementalism that the party has leaned on for decades. (This has more or less been made explicit by Democratic leadership.) But the outsize role of voting in shaping our own political subjectivity stretches across the political spectrum. And within the logic of the voter-as-consumer, trying to turn out skeptical voters who don’t feel that their vote has been earned can appear indistinguishable from a kind of vote-shaming.

In order to position themselves against this narrative, organizers are clear that voting in the presidential election is a cursory, if worthwhile, pit stop for building power on the left. The real change comes from sustained collective struggles like those that the Sunrise Movement and the movement for Black Lives are waging against the entire political establishment, said Neha Desaraju, Sunrise’s decentralized communications coordinator.

Groups on the left also draw a subtle but important distinction between organizing voters and arbitrating individuals’ choices to vote or not vote for Joe Biden. The multilevel failures of the political class, including the failure to fortify communities against the erosion of our democratic infrastructures, of course mean that some number of people will not vote for Joe Biden. But it’s impossible to know why someone is “disaffected” if no one is there to ask. As it is, our system includes no mechanisms to seek out the voices of nonvoters.

And as organizers keep telling me over and over, people are complicated: It’s not always clear whether someone stayed home because they felt alienated by both parties, or out of bitterness at the prospect of “rewarding” a party that has captured the nomination against their wishes, or because they have no desire to vote, or because they never received an absentee ballot. Each reason evinces a different illness with our democratic system, and each calls for a distinct kind of attention if the goal is to offer people some kind of buy-in into a political community or a political movement. So just as Mutual Aid groups and tenant organizing sprang up when the federal government failed to act on Covid-19 relief, groups like Vote Trump Out, Sunrise, and Mijente can fill the void left by the parties and be the first point of contact for broad swaths of people who deserve to have their needs heard. There’s also strength in commiseration: When Smucker goes door to door, there’s no need to pitch voting as a kind of compulsory civic duty. “If someone says, ‘Neither party is fighting for me,’ I say, ‘Don’t get me started, my mother lost her job in the financial crisis and no one was held accountable,’” Smucker said. Instead, Not Him, Us relies on what Smucker calls a “deep-listening” canvas—asking people what they want and need and offering an entry point into a majoritarian political movement that speaks to those needs.

Because it’s not just about Election Day. Reaching out to disaffected communities to invite them into this political moment has dividends beyond it, Smucker said. “Every time you’re talking to people en masse and making relationships and keeping track of who those people are, you’re building power.” Not Him, Us has recruited volunteers with a deep-listening canvas. And for Sunrise, connecting with young voters now will build up the ranks of people who they believe will be ready to participate in the next big climate strike or canvas for a candidate who respects their values down the line. As Desaraju put it, “getting out the vote is a tool to train and absorb more young people into organizing.” The difference between a broad effort to mobilize communities and a narrow crusade on behalf of Biden is made sharper by the reality of large-scale voter suppression and structural disenfranchisement preventing untold numbers of people from voting in the first place. The Latinx advocacy group Mijente, Smucker pointed out, sees no contradiction, for example, between its strong electoral ground game and its role serving undocumented communities. Those people cannot be left out of the strategy this cycle. As Wong told me, “Those who are serious about this work are onto the next campaign, the next electoral project. They’re not deliberating about one man … they’re thinking about all the other interventions that need to be made.”

One such intervention—perhaps the most immediate—is the pressing need to defeat authoritarianism, and as far as groups like Vote Trump Out are concerned, the liberal establishment is ill-equipped for the job. “Given the failures of the Democratic Party, we can’t really afford to count on them to win this without us,” said Sherrell. Desaraju, too, sees a gap in the Biden campaign’s strategy for turning out young people in particular, so Sunrise is stepping in to make sure that there is a robust youth movement ready to deliver Donald Trump a decisive loss.

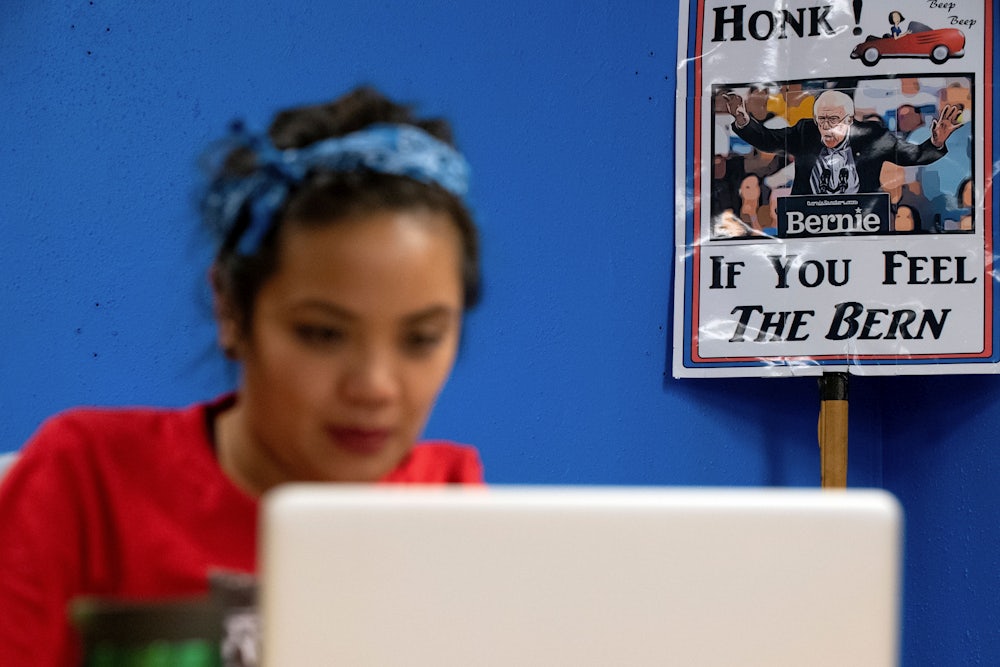

Then there are the other immediate advantages of a strong progressive showing in this election. Sunrise has been organizing hard in competitive down-ballot races like in Texas’s 10th district, where Mike Siegel, a union organizer and public school teacher, is running to oust a Republican who also happens to be Congress’s single-largest investor in the fossil fuel industry. But Siegel’s chances plummet if young people in Austin don’t show out in huge numbers, turned off by a bleak set of options at the top of the ticket. Shoring up a bloc of like-minded legislators in Congress is key to Sunrise’s climate agenda, so it can’t afford to foreclose on the kinds of victories it’s already seen with candidates like Ed Markey, Mondaire Jones, Jamaal Bowman, and Cori Bush. And even within a stubbornly centrist Biden administration, there may well be some room for more radical possibilities. “For example, it’s only by electing Biden that we can have Bernie as a chairman [of the Senate subcommittee] of public health,” Desaraju points out.

Just how many and what kind of concessions the left will be able to extract from Joe Biden is unclear, even among those who have already resolved to try. Some Sanders-crats, like Representative Ro Khanna from California, a former chair of the senator’s 2020 campaign, are optimistic that a Biden administration will be receptive to popular demands. That’s mostly, Khanna told me, because Biden is smart enough to see where political energy is concentrated. “He understands where the sentiment of the party is, where young folks are, and he sees the urgency of this moment. The public has an appetite for bold solutions, and he sees that.” One might fairly wonder what’s holding Biden back from doing any of that now, but it’s certainly more true for Biden than it is for Trump with whatever mandate he’ll perceive from a victory in November.

To some degree, this is also already happening. Sunrise has seen real success in shifting liberal institutional norms around its agenda items. Desaraju told me, for example, that the morning after Ed Markey won his primary race against moderate Joe Kennedy, Senator Chuck Schumer’s office called Sunrise to say that he wanted to help launch the Thrive Agenda, the movement’s eight-point plan for economic renewal. Technically speaking, Joe Biden is running on the most radical climate platform in the history of the party. But Sunrise forced its way into the public conversation through oppositional tactics like occupying Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s office, not because the establishment willingly handed it air time. Wong is strident on this point. “There’s no negotiating with a Biden administration,” she said. Grassroots campaigns will have to do a balancing act both to antagonize and work with the establishment. Smucker, too, doesn’t take anything for granted in terms of what to expect from a Biden presidency, even if it’s the organizations like his that ultimately help Joe Biden win in November. “I don’t think that us making a difference in this election … helping to elect Biden because we’re reaching the people that he can’t reach … is going to give us any purchase power in and of itself.” Jesse Myerson wrote last month that “nobody pays attention to individual nonvoters—that’s part of the problem—so nobody is in a position to be taught a lesson by anyone’s nonvote. On top of that, Democrats have shown themselves to be more or less immune to learning lessons from lost elections. They do it all the time and go back for seconds.” The inverse is also true: Voting for Joe Biden doesn’t mean that the party will, in something like gratitude, suddenly cater to the policy preferences of the left without someone to force its hand. Especially with the specter of Donald Trump gone, there’s no evidence that the Democratic Party will learn the lessons of a win any better than the losses.

In a kind of elegy for the Bernie campaign back in March, my colleague J.C. Pan wrote,

Since the 1970s, the gutting of the American labor movement and the steady rightward slide of the Democratic Party on economic policy has had the effect of consigning much of the left to niche activist spaces and the academy; the inevitable result of years of decline, in other words, has been a left that has no clear model of what electoral success even looks like.

For generations in this country, movement politics has largely been sequestered away from electoral politics. Still today, the mainstream account holds that voting is the mature, civic-minded thing to do, while protest, intraparty challenges, or striking on the picket line are often coded as the recalcitrant position of fringey malcontents. It’s hard to imagine, for example, all the celebrities proudly donning a “Vote” t-shirt this October being equally enthusiastic about putting their bodies on the front lines of uprisings for racial justice. But in 2016 and then again in 2020, Sanders offered a vision of how a political campaign could take shape from the traditions and values of a people’s movement. Both Wong and Smucker are career organizers who cut their teeth in the Occupy Movement and other grassroots struggles, but both of them say that it wasn’t until Bernie that they stepped into the world of electoral work. And ironically, it’s possible that the collapse of the Sanders campaign will blur these boundaries even more. Wong thinks so. “The [establishment] didn’t actually neutralize Bernie’s movement. They just decentralized it further. They’re looking around at the political terrain on the left and saying, ‘Is it over?’ And they’re realizing, day by day, that it isn’t.”

The worlds of movement and electoral politics have more overlap now than ever. Youth movements like Sunrise have been incredibly, almost singularly, deft at moving between the two worlds and knitting them together at the seams. What they’ve seen, and what they intend to capitalize on, is that for better or worse, elections are still an arena in which transformative, majoritarian and working-class politics can be done, even when the candidate himself is obstinate. “There is no long-term vision for Biden’s strategy, but there is a long-term strategy for our vision.” Desaraju said. “He is key to our strategy and our plan.” The left has always had to forge a path through a political world not of its own making. But by harnessing the energy and the attention of this supercharged moment and directing it beyond November 3, there may be an opportunity to shift the balance of power altogether.