The Marathon County Historical Society sits in an old church building in Wausau, just up the Wisconsin River from the town of Mosinee. The lobby is large, a gift shop with books and paraphernalia in one area and temporary exhibitions in another. “Milking Time: The Evolution of the Dairy Industry in Marathon County” was on display on the day of my visit, in June 2019. I had called ahead, and a librarian was waiting for me. He settled me into the reading room and brought out a wide and shallow box, informing me that they usually got one or two visitors a year who were interested in the backstory of the coup.

This was a pilgrimage, of sorts. I had come to Mosinee in search of evidence of events that took place here nearly 70 years earlier. In 1950, just three months after Joseph McCarthy, the U.S. senator from Wisconsin, warned of “enemies from within” in his infamous speech in Wheeling, West Virginia, the residents of Mosinee decided to show the world the true horror of communism by staging a fake Communist takeover of their town. The event—featuring costumed citizens, fake concentration camps, and an all-too-real death toll of two—was envisioned as a representative “pageant,” a fear-driven demonstration of a possible future.

Just last month, Donald Trump himself traveled to Mosinee as well. He was there to hold a “Great American Comeback” rally at the town’s Central Wisconsin Airport, seeking to turn around the fortunes of his flailing campaign with a receptive audience in a key swing state. This was his second trip to Mosinee; a 2018 rally drew crowds that waited for 29 hours in the October chill to glimpse him.

I had gone to Mosinee as a student of history. Trump went as its tragicomic reenactor, treating his audience to a performance that rhymed with many of the country’s darkest moments. As he thundered about left-wing mobs overrunning our cities, I could not help but think of the faux coup in 1950, a pure yet largely forgotten example of the paranoid style in American politics. The event presaged our present, but the residents of Mosinee could not have known how spectacularly their descendants would surpass them.

My fascination with Mosinee began in the halcyon days before a Trump presidency, when I was a graduate student studying the politics of fear. Think of the onset of the war on terror after 9/11, or the often xenophobic reactions to the Pearl Harbor attack. I focused largely on the Cold War, examining how fears of communism ran rampant, stoked by politicians of both parties, birthing domestic and foreign policies that would shape the decades ahead.

As anyone who has been masochistic enough to write a dissertation will know, social scientists in training spend much of their days leafing through volumes in search of inspiration. As the pages blurred with blacklists of authors and academics, their lives and livelihoods suffocated by the Red Scare, the story of Mosinee caught my eye. In 1950, the American Legion in central Wisconsin, deciding that President Harry Truman was not taking the threat of communism seriously enough, took matters into its own hands. On May 1—International Workers Day—the Legion staged the fake Communist siege on Mosinee, calling in the national press to capture “14 hours of the most smashing, dramatic demonstration of what communism really is.”

The event was the brainchild of World War II veteran John Decker, who believed that drastic action was required to “elevate the debate to reach minds we hadn’t reached.” Mosinee—a town of fewer than 1,400 at the time—was selected as the site of the coup because a prominent legionnaire owned and edited the town’s newspaper. Two former Communists were brought on as technical advisers to add authenticity to the day’s events.

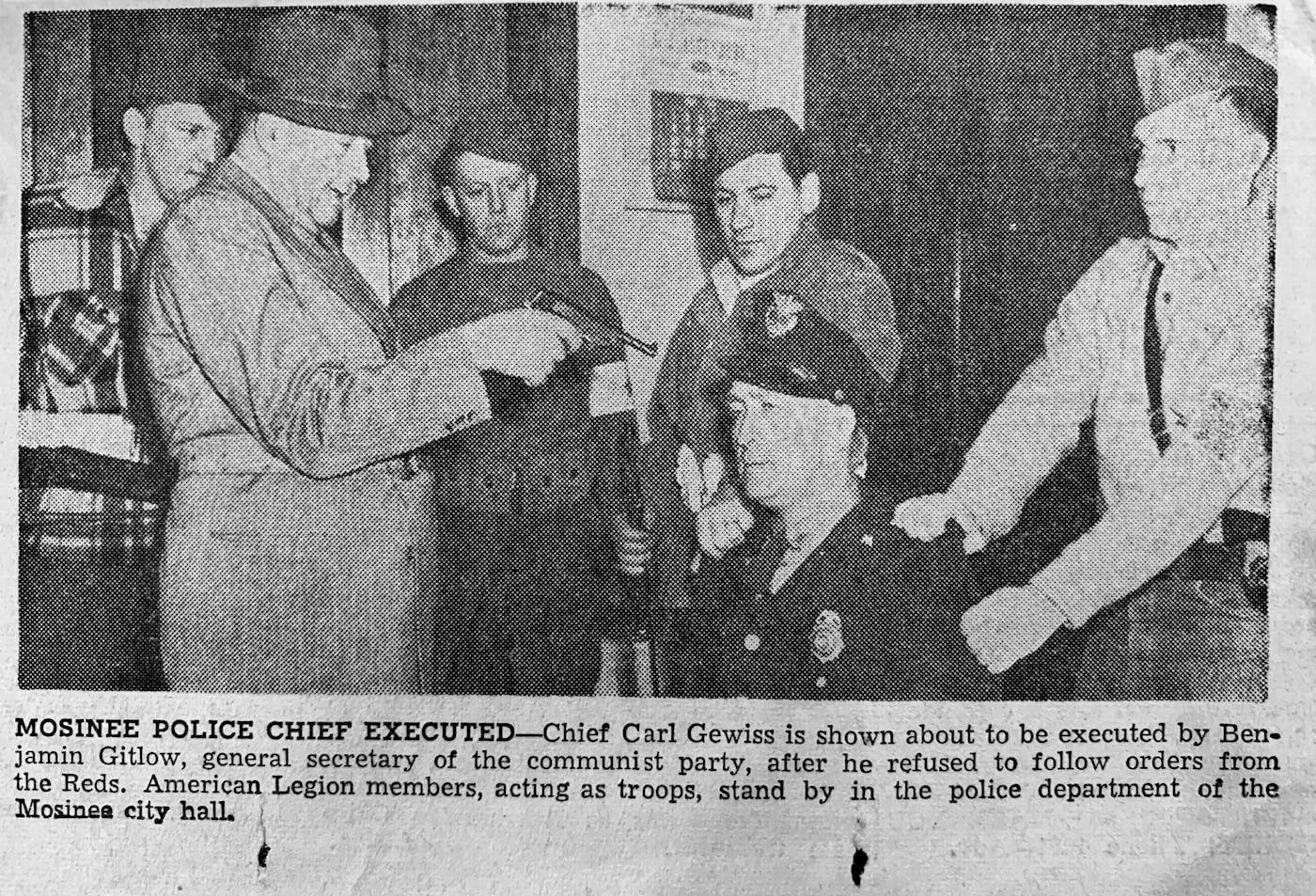

The “pageant” began with a “Communist Combat Team” of costumed volunteers “arresting” the mayor and chief of police at their homes and placing local clergy and business leaders in a “concentration camp.” The organizing committee issued ration cards and entry and exit passes, erecting roadblocks and questioning those who came through. Local businesses got in on the action, too; the movie theater played propaganda reels; and merchants raised their prices, served only Russian fare, or otherwise made market transactions a nuisance. A sweet shop placed a sign on its shelves: “candy for communist youth members only.”

At the end of the day, according to the official Schedule of Events, the entire town would “cast aside their subversive roles and join in the raising of the American flag.” Boy Scouts would “burn all Communist banners, etc. in a huge bonfire” before the whole crowd would join in singing “God Bless America” and “start peacefully home, thankful to God that they live in AMERICA.”

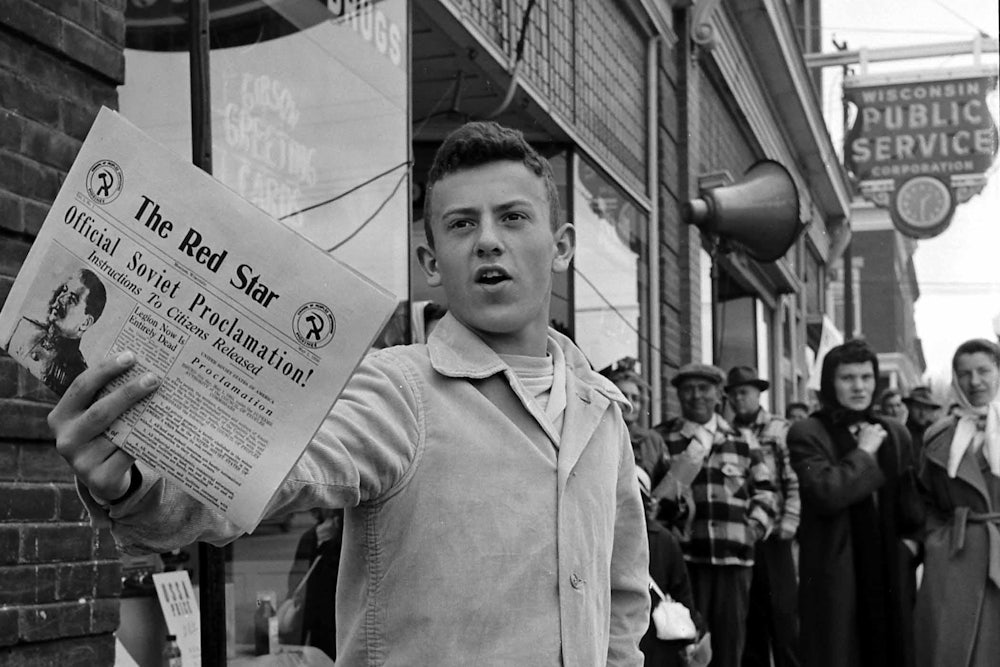

More than 60 news outlets recorded the day’s events, jockeying to get the best shot, and the event was featured in over 1,200 newspapers nationwide. Life ran a story with a full page of pictures depicting the “torture” of the police chief, a child in uniform giving the Red salute from his father’s shoulders, and the arrest and imprisonment of the local paper mill staff. “During the day,” the latter caption read, “most Mosinee citizens submitted good-naturedly to being pushed about by invaders.”

Though it was considered a wild success, the day ended in tragedy. As the Wasau Daily Record-Herald blared, “Two Mosinee Men Who Had Roles in ‘Red Coup’ Program Are Dead.” The mayor and a local reverend died within days of the coup, and both deaths—variously reported as heart attacks, cerebral hemorrhages, or stroke in different publications—were attributed to Mosinee’s day under Communist rule. As Life’s coverage concluded, this was an unfortunate coda to “Mosinee’s most exciting day since the business district burned in 1910.”

This event, a perplexing mix of fear and absurdity, of the comic and the catastrophic, became one paragraph in my dissertation. I saw it as an amusing anecdote, evidence of the ways in which fear of communism manifested in public life in the early Cold War. But behind the town’s antics was a grim reality—at the same time these citizens were playacting, the very fear they were channeling was destroying reputations and inspiring draconian legislation and locking the United States into decades of hardened ideological conflict. It was far funnier, far simpler, to dismiss the Mosinee pageant as the quirky delusion of a small town and the deaths of the two men as a regrettable accident.

While I was researching and writing my dissertation, Donald Trump morphed from punchline to president. His campaign soared on wings of fear, feathered with racist warnings of Mexican rapists and gang warfare. He both appealed to and created a terrified public; in 2016, fears of terrorism and crime were at a level not seen since 9/11. After riling his followers into frenzy, he offered them a path toward security: “I alone can fix it.”

In the years since his victory—years in which I finished my degree and moved to Washington, D.C., to join the legions of people seeking to combat our new aspiring authoritarian—I found myself thinking often of the Mosinee coup. At first, it was simply a curio that I could deploy to translate my years of abstruse academic work into general understanding. But it became something more. I soon saw that its absurdity was the cloak under which fear stalked.

My obsession reached new heights in June of last year, when I took a week off from work to travel to Mosinee, beginning my trip at the Marathon County Historical Society. The box that the archivist handed to me contained a hodgepodge of photographs, newspaper clippings, and objects. I pulled out a washed-out pink newspaper that had clearly once been red, titled The Red Star, the special edition that the Mosinee Times issued for the day. The front page included a testimonial to Stalin—“our beloved … the man of steel with a heart of cold granite”—as well as notices on the forthcoming confiscation of automobiles and the Mosinee Young Communists League meeting in the high school gym. The paper also noted that the American “Legion Now Is Entirely Dead.”

I found photos of the “execution” of Police Chief Carl Gewiss, sitting stoically in a chair as the “general secretary of the communist party” held a pistol to his head. Another picture showed two reporters from Detroit, identifiable by their armbands, grinning at the camera, clearly tickled by the day’s events. A Record-Herald photo captured “small fry” Billy Knoedler, age 4, with his right fist thrown into the air in salute and a cowboy pistol hanging on his left hip.

I found the actual Communist Party of Wisconsin’s rejoinder to the pageant. On the morning of May 1, it had blanketed Mosinee with leaflets titled, “So This Is Supposed to Be Communism—Says Who?” They argued that this portrayal of communism was put forward by “The Boss … who owns the mills,” “American Legion Big Shots … who do what the mill owners tell them,” and “Stoolpigeons … who are paid plenty by the mill owners for lying and double crossing labor unions.”

There was a red star to be worn on one’s lapel. A white armband with “Security Police” stamped across it, part of the uniform for those playing Communist law enforcement. There were factory passes, ration permits, camera permits, gasoline permits, exit permits, entry permits, citizens’ identification cards—all stamped with a hammer and sickle and “The Council of Peoples Commissars.” A faded red flag.

Going through the materials, I could not help but wonder whether the Marathon County Historical Society was preparing another box for the next overeager researcher. A box filled to the brim with MAGA hats, QAnon buttons, and a few photos of counter-protesters with signs proclaiming, “Love Trumps Hate.”

On September 17, 2020, Trump landed at the Central Wisconsin Airport in Mosinee. Taking the stage to “God Bless the USA,” Trump launched into a nearly 90-minute frenetic monologue. He excoriated Joe Biden’s long career “offshoring Wisconsin jobs, outsourcing your factories, throwing open your borders, dragging us into endless ridiculous foreign wars, and surrendering your children’s future to China.” He proceeded to discuss, among other subjects: left-wing mobs, flag-burning, violent criminals, ISIS, the Big Ten, “Oh, Canada,” Confederate statues, Sean Duffy’s tree-climbing ability, the suburbs, CNN, Hillary Clinton, the Nobel Peace Prize, Hunter Biden, Kenosha, Congressman Bryan Steil’s handsomeness, Covid-19, the wall, Nancy Pelosi’s hair salon, the end of cash bail, Biden’s “manifesto,” the Green New Deal, and the Green Bay Packers. Upon concluding, he departed for Air Force One, the song “YMCA” pumping in the background.

During the rally, Trump never mentioned anything unique about where he stood, never even uttered the word “Mosinee,” though he came close when he said the crowd was full of “good people, right here in … give me the proper pronunciation. That’s right, thank you, that’s what I said.” It was just another crowd, just another town in a swing state, just another airport where he could show off the trappings of his office, provoke his detractors, and delight in the adulation of his audience.

But Trump’s performance was haunted by the ghosts of Mosinee’s past, starting with Joseph McCarthy. To be sure, despite the clear parallels between the two men, Donald Trump is no McCarthy. He is far more dangerous. McCarthy was a junior senator loathed by his colleagues, shunned into official irrelevance in 1954 after going after the Army. Trump is the president of the United States, and his party has fallen into line, no matter whom Trump attacks, very much including members of the military.

Even with his comparative lack of power, McCarthy made his impact felt far beyond his Senate career. He did not start America’s anti-Communist obsession, but as its preeminent “bomb-thrower,” in the words of Louis Menand, he thrived on outrageous and unprovable accusations, playing a different political game than that of any other politician at the time. He claimed a vast governmental conspiracy and magnified the chaos that followed. His legacy outlived him, metastasizing to ruin lives well beyond his premature death in 1957.

Today, Trump has breathed paranoid life into conspiracies galore. He’s embraced QAnon, whose supporters believe that a satanic pedophiliac cult is being run in part by the most powerful members of the Democratic Party. He’s boosted the standing of white supremacists peddling the “great replacement” theory of impending white genocide. And he’s offered support to armed right-wingers who descended on cities this summer to counter anti-police protests, one of whom has been accused of killing two people in Kenosha, Wisconsin, just over 200 miles from Mosinee.

Where McCarthyites drew up blacklists and paraded through small towns in Communist garb, Trump’s acolytes murdered dozens in Pittsburgh and El Paso, shot up a pizza restaurant in Washington, D.C., and mailed pipe bombs to prominent Democrats. They now threaten to become part of the formal machinery of government, elected to our nation’s legislatures.

Should Trump leave office in January 2021, we will still be left with many people who have been led to believe, just as the people of Mosinee believed, that their way of life is under existential threat from a vicious, bewildering other, whether it’s antifa looters or deep-state sex-traffickers. But unlike the people of Mosinee, who knew they were putting on a show, these modern-day fantasists are convinced that the pageant is real.

The story of Joseph McCarthy is often taught as a parable: a regrettable demagogue defeated when Americans came together to reject the politics of fear that have been so prevalent in other countries. He represented, to these storytellers, the road not taken, a temptation turned aside. Now he looms like a premonition of our present moment.

The legionnaires of Mosinee were not personally directed by McCarthy, and the QAnon activists of tomorrow, too, will find inspiration in Trump well beyond his tenure. What lessons Trump will offer to future Americans hinges on what we do next—on the relics we will make, the materials we leave to a budding researcher opening a wide and shallow box in a local museum.