Over the past four years, there have been dozens of books published about Donald Trump. Some have recorded his numerous failures and general incompetence, others his Churchillian magnificence and world-historical accomplishments. They have documented his real, imagined, and unverified ties to Vladimir Putin; his mental state (he is either a genius or suffering from a host of DSM-5 disorders); his thuggishness and authoritarianism; his role in the demise of the Republican Party; and the various political and social movements that have emerged in response to his provocations. There have been books that try to situate the president in American history, to explain the present, and to ensure this doesn’t happen again in future. All of these books, in one way or another, aim to answer the question on everyone’s mind: Just what, exactly, is happening?

And now, for some reason, we also have a book about all of those books.

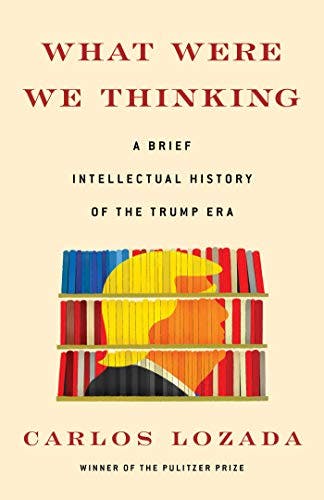

Carlos Lozada’s What Were We Thinking aspires to be an omnibus volume, a mosaic composed of the best (and worst) of the myriad books about Trump’s presidency—an “intellectual history” (to use Lozada’s subtitle) of the last four years. What Were We Thinking is, instead, not much more than the sum of its many quotations. A mirror image of the vast majority of the 150 books under review, it is a muddled work that aspires to reckon with this strange, bewildering period but is instead swallowed up and contorted by it. What Were We Thinking is most useful as an indication of just how thoroughly our lives have been overwhelmed by the Trump presidency—and how far we still have to go to make sense of the very recent past.

Much of the problem lies in the material. As Lozada acknowledges, “Individually, these books try to show a way forward. Collectively, they reveal how we’re stuck.” One can’t imagine a longer way around the barn than reading 150 nonfiction books to identify the very basic problem all of us are facing right now: We want to find a way out of this mess. Why are works of nonfiction a better guide to the present moment than, say, movies or speeches or TikTok videos? Well, because Lozada is the nonfiction book critic at The Washington Post.

Although he has a set of favorites—including Timothy Snyder’s Facebook post-turned-pamphlet On Tyranny, the Mueller Report, American Enterprise Institute scholar Yuval Levin’s A Time to Build, and Michael Lewis’s The Fifth Risk—few of the books on offer provide a great deal of insight. “If journalism is still history’s first draft, then books remain the first draft of how we think about that history, how we seek our place in it,” he writes. The confusing repetition of “first draft” here raises some questions. If journalism is the first draft of history, shouldn’t books be … second drafts? Third drafts? At any rate, what Lozada has given us is a rough draft about rough drafts.

In prose that channels the roundtable copy of a prize committee, he notes that the best books “enable and ennoble a national reexamination—one that Trump has attempted to carry out on his own and on our behalf. They are the books that show how our current conflicts fit into the nation’s story, that hold fast to the American tradition of always seeing ourselves anew.” What Were We Thinking plays out, in contrast to this ideal, as a series of capsule reviews. This approach calls to mind one of those Very Short Introduction books, and it is unclear why anyone would need to read a Very Short Introduction to the last four years when we have just lived them.

Lozada is a critical Goldilocks, searching for a Trump book that’s not too hot and not too cold. The works of Trump sycophants like Hugh Hewitt and Jeanine Pirro are embarrassments, he concedes. On the other hand, the anti-Trump works of Republican defectors and Lincoln Project types lack credibility—there is not enough introspection about the GOP’s pre-Trump drift into nativism and demagoguery.

Resistance literature, meanwhile, is too partisan. Lozada depicts writers such as Naomi Klein and, uh, the founders of Indivisible as mini-Trumps working to exploit this political moment for liberal causes. (Klein is condemned for urging a new kind of “shock doctrine”—for raising the minimum wage and fighting climate change. How unseemly!) In general, he plays Henry Higgins to the pussy hat–wearing Elizas. “To imagine that you can adopt the ruthlessness of Tea Party–style tactics yet stop short of pursuing them to your own political endgame is to be enormously confident about your self-control,” he chides.

The pundits Lozada admires the most are those who are above the vulgarity of politics and stress commonality and institution-building. Snyder is admired for reminding readers that “ideas about change must engage people of various backgrounds who do not agree about everything” and that they should “make eye contact and small talk.”

Without a larger argument about Trump books, Lozada has, perhaps accidentally, written one of his own: In this case, one that scolds partisans on both sides, makes a case for the value of liberal bureaucracy, and frets about a political system increasingly allergic to compromise. It’s the kind of argument you could expect David Brooks to make.

Lozada gets more interesting the further away he gets from Donald Trump. His chapter on books about immigration, rooted in Lozada’s own experience, is mournful, noting that “diversity and acceptance are far from America’s only values; the arc of the moral universe may bend toward justice or it may snap back in our faces.” But he can also be tin-eared, writing, “All immigration involves family separation; to compound it at the border only adds more pain and uncertainty to the sacrifices immigrants already must make.”

In his chapter on identity politics, he assesses the works of writers from Ibram X. Kendi and Robin DiAngelo to Bari Weiss and Wesley Yang. He attempts to synthesize what he sees as the best parts of the arguments made by all parties and lands precisely nowhere: “The only way to protect and uphold the individual—every individual—is through universal rights and principles so yes, we must move toward a politics of solidarity,” he writes. “But for solidarity to endure, for it to mean something real for everyone, we must grapple with the politics of identity.”

Everything, however, must always come back to Trump. Reading every Trump book is certainly a triumph of endurance, but it’s never clear if it’s a worthwhile one. Much of the time, Lozada seems to be phoning it in. (“It’s the funniest of the Chaos Chronicles but The Toddler In Chief also outlines the serious risks of having a president with childlike traits,” he writes about his colleague Dan Drezner’s book. Thanks for the tip!) It all has the feel of a homework assignment, albeit a familiar one, since we have all spent the past four years searching for meaning. There is no argument or revelation in What Were We Thinking that couldn’t have been gained without reading 150 books about Donald Trump. The big revelation of this book may, in fact, be just that: Don’t read 150 books about Trump.